In

Blog 2023

burcu dogramaci

In her work

Die Bücher (2019/20, fig. 1 + 2), the artist Annette Kelm compiled photographs of book covers of volumes that were destroyed in the ritual book burnings of the National-Socialist era. In the campaign

Wider den undeutschen Geist (Against the Un-German Spirit) promoted by the German Student Union, book pyres were erected and set alight in numerous German cities on 10 May 1933.

Fig. 01: Kunsthalle zu Kiel, exhibition view Annette Kelm. Die Bücher, 2022 (© Kunsthalle zu Kiel, photo: Helmut Kunde). Lilli Körber’s Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag on the far left.

Fig. 02: Kunsthalle zu Kiel, exhibition view Annette Kelm. Die Bücher, 2022 (© Kunsthalle zu Kiel, photo: Helmut Kunde).

The published lists of books ‘worthy of burning’

[1] also included those photographed by Annette Kelm. Her photographs show the covers of 50 first editions of the publications that were burned in the

auto-da-fé.

[2] The inkjet prints, measuring 52 x 70 cm, show these books in the same bright illumination, with a drop shadow visible that emphasises their three-dimensionality, indicating that these are photographs of objects (not just of the front cover, for example). The photographs show the absent real object, whose contents remain illegible, as Robert Kehl points out in his review in the journal

Texte zur Kunst. This shifts the accent from the book as an object of remembrance to the aesthetic diversity of book design, referring to the network of artists and designers of the Weimar Republic and thus problematising the never-linear act of commemoration.

[3] In his argumentation, Kehl contrasts the factual and conceptual colour photography with the black and white of the historical photographs of the book burnings.

[4] However, Annette Kelm’s expandable series contains more complicated implications that apply equally to Nazi book burning, persecuted writers and destroyed books as well as to the displacement of people and objects. I argue that, through Kelm’s photographic conceptual art, a contemporary audience can re-connect to the dis:connected publications and designs that were dispersed and therefore lost to a German audience due to Nazi persecution.

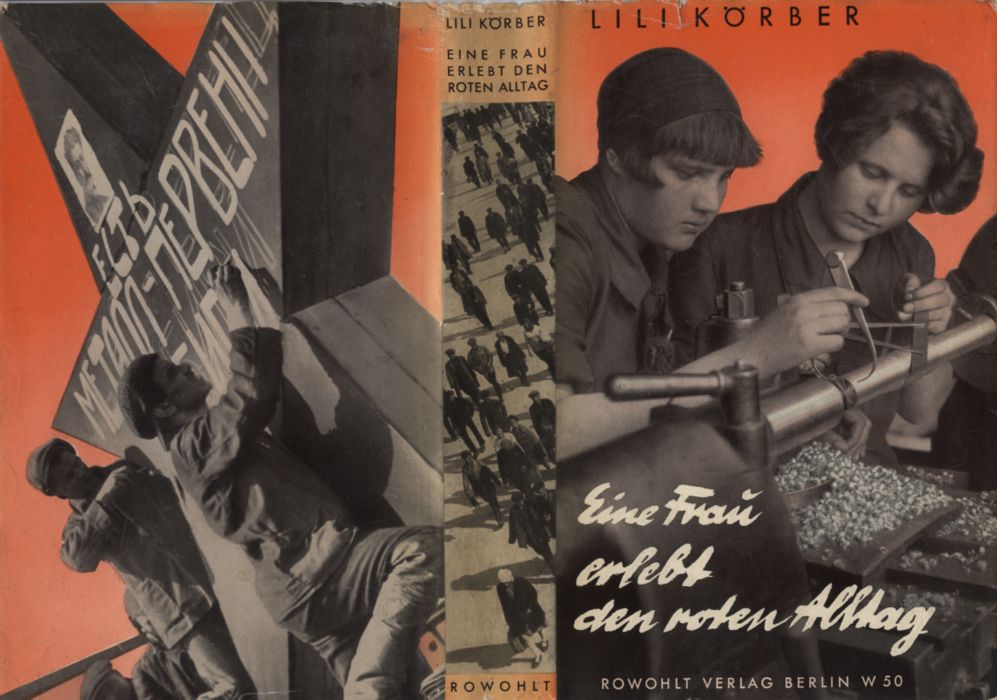

Among the photographs (and, thus, also among the burned books) are several covers designed by John Heartfield: F.C. Weiskopf’s

Umsteigen ins 21. Jahrhundert (1937) and Upton Sinclair’s

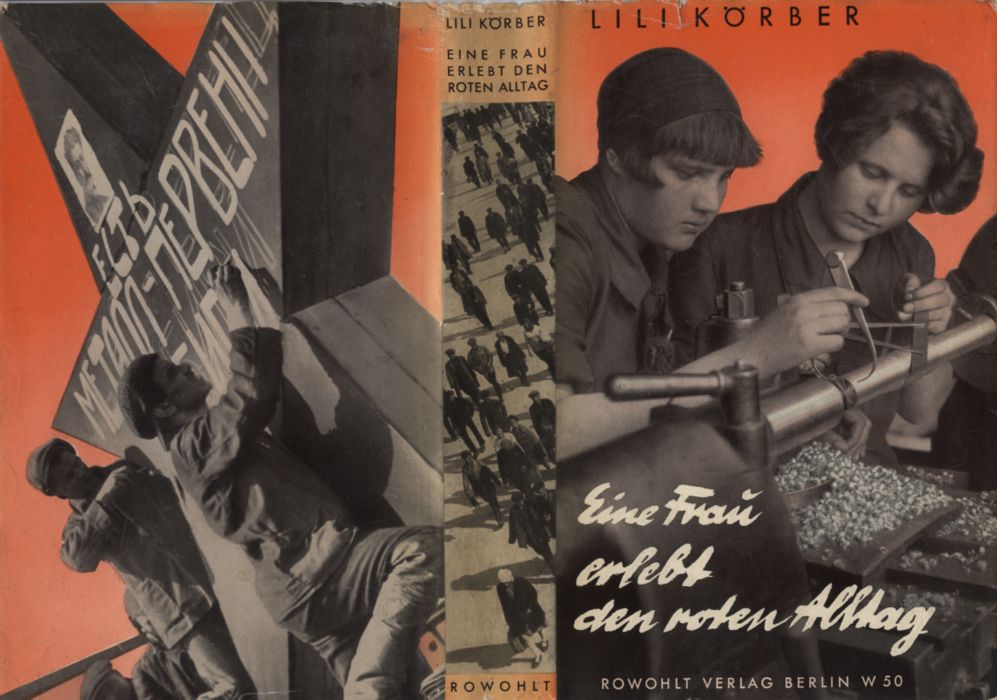

Das Geld schreibt (1930), both published by Malik publishers in Berlin. Also tossed upon the pyre was Lili Körber’s

Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag from 1932, which was published by Rowohlt Verlag with a book cover by Heartfield and is the starting point for my reflections (fig. 3).

An author, a graphic designer and a book – entangled histories

The literary scholar and writer Lili Körber was born in Moscow in 1897 as the daughter of an Austrian merchant family, and she later lived in Vienna. She was a member of the Social Democratic Workers’ Party, the Union of Socialist Writers and the League of Austrian Proletarian Revolutionary Writers. This political commitment was also expressed in her journalism; Lili Körber wrote for leftist print media, such as the

Wiener Arbeiter-Zeitung, the

Rote Fahne and the

Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (

AIZ).

[5] Together with Anna Seghers and Johannes R. Becher, she accepted an invitation from the Moscow state publishing house to travel to the Soviet Union in 1930. Fluent in Russian, she decided to get to know the living and working conditions of the people by serving as a driller in the Putilov tractor works in Leningrad for several months. It was a factory with a ‘well-known history of revolutionary resistance during the tsarist era’.

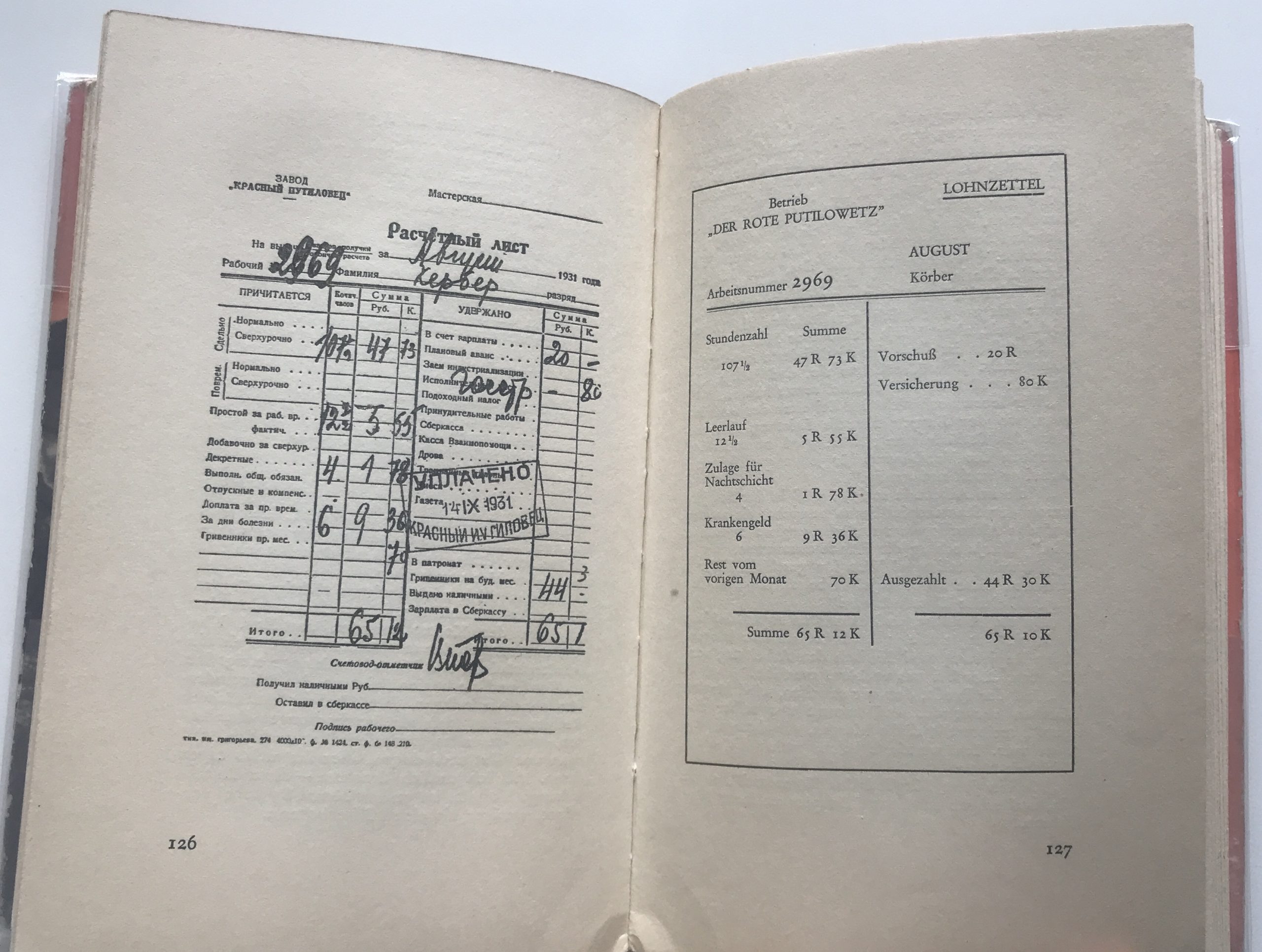

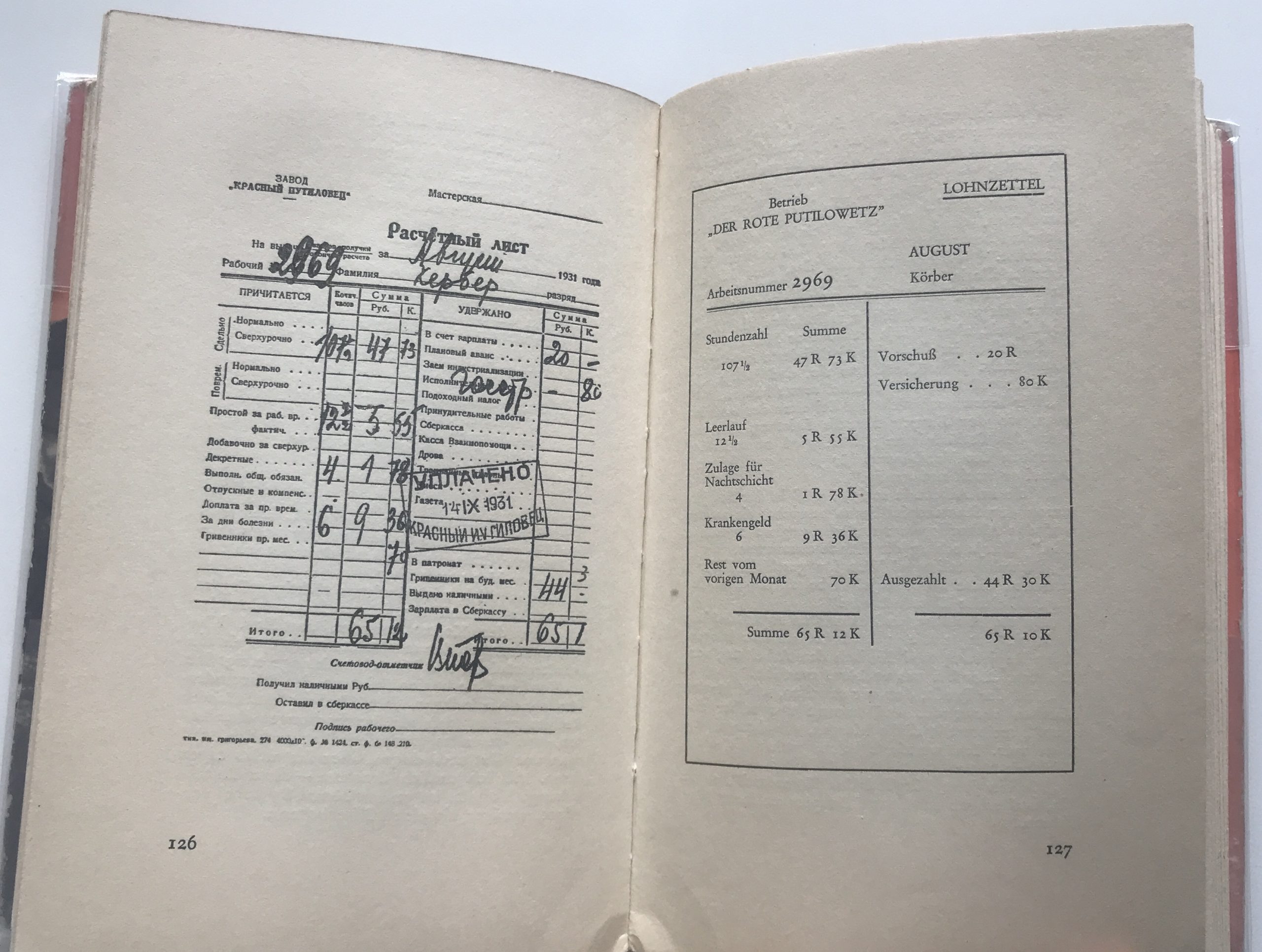

[6] Körber published her experiences as

Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag (A woman experiences the everyday life of the Reds), a book published by Rowohlt Berlin in 1932 that runs to 239 pages. The author worked in the genre of documentary novels by reproducing documents such as pay slips and pages from her work logbook in addition to passages from her diary, which convey authentic and personal experiences (fig. 4). The book was a bestseller and was reviewed in the press by, for example, Siegfried Kracauer in the

Frankfurter Zeitung, and the run of 6000 copies was sold out in four weeks.

[7] No further editions were ever published.

[8]

Fig. 03: Lili Körber. Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag. Berlin: Rowohlt, 1932, cover design by John Heartfield, cover, spine and back (Archive Burcu Dogramaci, © The Heartfield Community of Heirs / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023

The book cover was designed by the artist John Heartfield. The volume was published as a paperback with a dust jacket. Heartfield used three photographs for the cover, spine and back (fig. 3): at the front are two women with short haircuts measuring a milled steel piston. The photograph is cropped against a coral background that connects the three outer edges of the cover. The spine displays a square, with people walking in groups in the same direction (downwards in the picture) towards a common goal that lies outside the field of view. It could be a factory gate. On the back cover workers are erecting a large Soviet star and painting it with white Cyrillic letters; the lettering ‘There is metal’ refers to the accelerated construction of the metalworking industry in the Stalinist five-year plan.

[9] Stalin’s likeness is presumably attached to the top.

The three photographs work with dynamic lines. In front, the women look downwards, while tools and processed material point from the left to the top right. The crowd strides towards the bottom of the picture, the workers and the star are dynamically arranged from bottom left to top right. Heartfield’s design alludes to the content of the book: Körber’s experiences as a driller are echoed in the motifs of the workers, with the Soviet context on the back of the book. The dynamic composition again refers to the author and heroine's constant struggle with social and political circumstances as described in the blurb, which reads: ‘In workshops and hospitals, in furnished rooms and on the street, she fights day after day, with pleasure and agony, the heated lovers’ quarrel between the individual with the collective. Again and again balance is restored, and again and again the quarrel resumes’.

[10] In addition, the cover in particular conveys an image of contemporary women and female workers in the Soviet Union, who outwardly resemble the New Women of the Weimar Republic.

[11]

Fig. 04: Lili Körber. Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag. Berlin: Rowohlt, 1932 (Archive Burcu Dogramaci).

For his book and magazine covers, John Heartfield worked with the technique of photomontage, combining existing and specially taken photographs such that new meanings emerged. On the title page and in the pictures inside the

AIZ, Heartfield brought together photographs from different contexts in one pictorial space. Through ‘the aesthetic closure of the cuts between the different photographic parts’

[12] a new pictorial logic emerged, as Vera Chiquet notes. Heartfield’s photomontages for the

AIZ used artistic means and pictorial constellations to expose the economic entanglements of National Socialism, the viciousness, the aggressiveness, the anti-Semitism of Nazi ideology. In his book covers, produced from 1920 onwards for publishers such as Malik (the publishing house run by Wieland Herzfelde, Heartfield's brother), Neuer Deutscher Verlag and Rowohlt, Heartfield used photographic material to translate books’ contents into artistic forms.

[13] The ‘seductive aesthetic’

[14] attracted attention on display tables and bookshop windows, and it drove sales along with the content, which was advertised via blurbs and reviews.

Dispersion – John Heartfield and Lili Körber in exile

Due to his political work, Heartfield had to flee to Prague as early as 1933, before continuing his artistic work for the

AIZ. Like Heartfield, Körber, as a political author, quickly found herself in the crosshairs of the new rulers. Her 1934 novel

Eine Jüdin erlebt das neue Deutschland (A Jewess Experiences the New Germany) ‘one of the first anti-fascist books’,

[15] takes place in the transitional period between the end of the Weimar Republic and the establishment of the Nazi state, incisively observing the ideological suffusion of society. The list of harmful and undesirable literature (here as of October 1935), contains ‘Sämtliche Schriften’ (all writings) by Lili Körber.

[16] In 1933,

Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag was among the books burned.

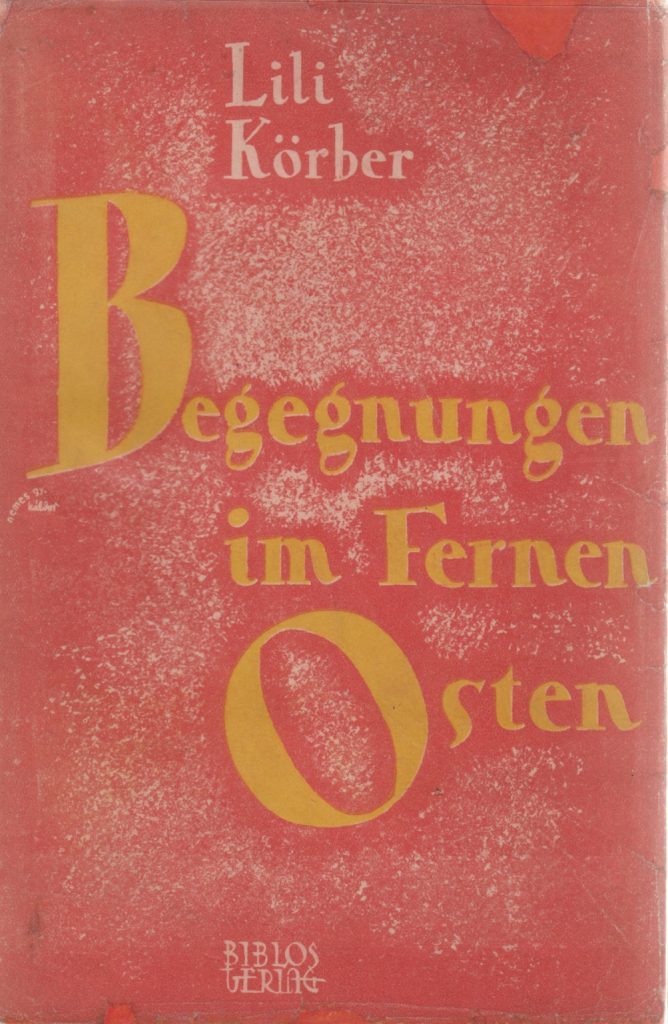

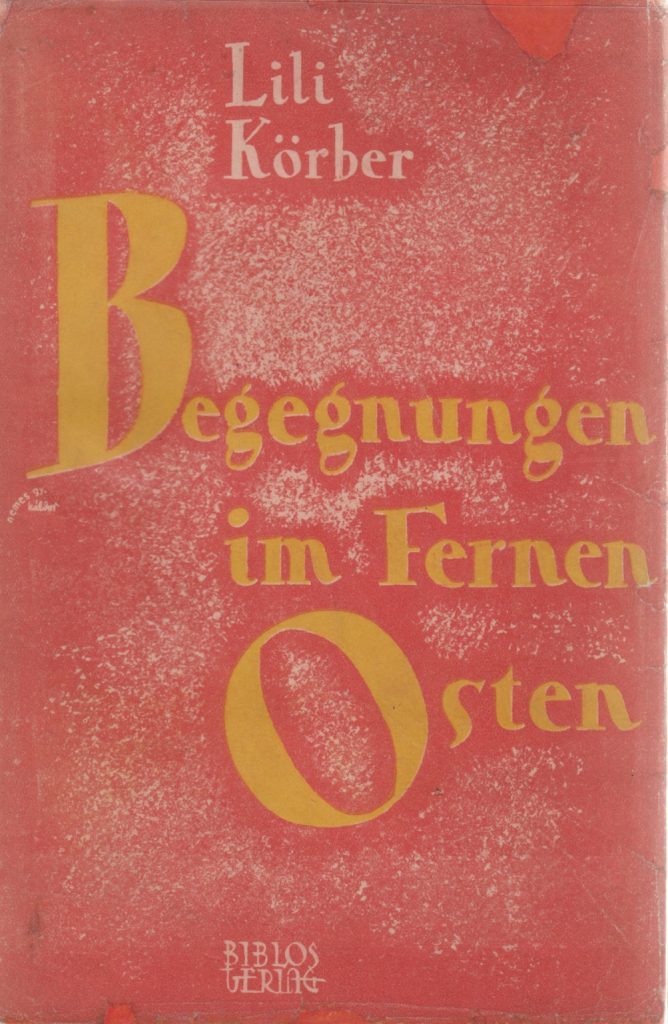

[17] A trip to Japan and China in 1934 found literary expression in the travelogue

Begegnungen im Fernen Osten (Encounters in the Far East, Biblios publishers, Budapest, 1936, fig- 5) and in

Sato-San, ein japanischer Held. Ein satyrischer Zeitroman (Sato-San, a Japanese Hero. A contemporary satyrical novel, Wiener Lesegilde, Vienna, 1936), which is a reflection on Japanese fascism that can also be read as a parody of Hitler. It thus becomes clear that the burning and banning of her books under National Socialism did not deter Körber from publishing political works.

Fig. 05: Lili Körber. Begegnungen im Fernen Osten. Budapest: Biblios publishers, 1936. Cover. (Archive Burcu Dogramaci).

Farewell shortly after the annexation of Austria, Körber fled Vienna to Paris via Zurich, where she wrote for Swiss newspapers and the

Pariser Tageblatt.

[18] From April 1938 onwards, the social-democratic newspaper

Volksrecht in Zurich published the serial novel

Eine Österreicherin erlebt den Anschluß (An Austrian woman experiences the annexation), in which Körber, under the pseudonym Agnes Muth, processed her observations in the proven form of an autobiographic novel. Finally, in June 1941, with the support of the Emergency Rescue Committee, she emigrated via Lisbon to New York, where Körber worked in a factory worker and as a nurse.

[19] In addition to a few newspaper articles in, for example, the émigré newspaper

Das andere Deutschland (The Other Germany) published in Buenos Aires, she also published the serial novel

Ein Amerikaner in Russland (An American in Russia) in the New York ‘Anti-Nazi Newspaper’

Neue Volks-Zeitung in 1942/43.

[20] Körber fell off the radar in Germany and Austria; her disappearance was the result of political persecution, the confiscation and destruction of her books and her emigration.

[21]

On the occasion of her 125th birthday, Lili Körber, who died in exile in New York in 1982, was described in a February 2022 newspaper article as ‘none forgotten, but today even a virtual unknown’.

[22] This radical judgement must read in the context of the growing scholarly attention paid to her work in recent years. In the 1980s, two of her books were reissued in the wake of ascendant research on women writers and a burgeoning interest in exiled women. In 1984, persona publishers in Mannheim published

Die Ehe der Ruth Gomperz (The Marriage of Ruth Gomperz), a re-edition of

Eine Jüdin erlebt das neue Deutschland under a new title, and in 1988 the Brandstätter Verlag in Vienna reprinted

Eine Österreicherin erlebt den Anschluß.

[23] Körber’s book

Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag has not been re-published to date, but it has been discussed in a number of academic papers.

[24]This attention to Körber’s book can be attributed to the fact that male perspectives dominated reports on Russia until 1933, among other reasons. In the approximately 100 German-language reports published on Russia, there were only five other women besides Körber.

[25]Nevertheless, the 1991 essay by the art historian Herta Wolf is entitled ‘Lili Körber – An Emigration into Oblivion’,

[26] and the literary scholar Gabriele Kreis, who knew Körber personally, stated in 1993: ‘For the Austrian Lili Körber, exile meant the end of her existence as a writer. It turned her into a writing nurse. [...] When I asked her why she became a nurse, she answered: “It was the feeling that you can really do something in this profession, that you are needed.” As a writer, Lili Körber was no longer needed in Germany and Austria’.

[27]

As for John Heartfield, art history has undoubtedly not forgotten him. Rather, he is especially popular exponent of the Weimar Republic. His exile work, on the other hand, long received less notice. It was seen as subordinate and less political. John Heartfield fled from Prague to London in 1938, where he continued his work in various fields, as a member of the Free German League of Culture for example, composing title pages for magazines such as

Picture Post, but above all as a designer for book covers. Heartfield designed numerous book covers between 1941 and 1949, especially for the publishing house Lindsay Drummond. These display both the continuation of his artistic means as well as the political orientation in his work.

[28] The Lindsay Drummond publishing house, founded in 1937, had an anti-fascist programme that included books by politically active émigré authors. Not every book Heartfield designed for Drummond had a political impetus, but numerous publications were directed against the Nazi regime and its expansionist policies; they were devoted to wartime England and the

Future of the Jews.

[29] The book jacket of Wilhelm Necker's

Hitler's War Machine and the Invasion of Britain (1941) shows a tank driving away from the viewpoint. The soldiers are captured from behind; parachutists and an aeroplane can be seen in the sky above. Soldiers in ranks, tanks and uniformed men marching are visible on the reverse. The visual symbolism depicts the Nazi army as technically advanced and disciplined; man and machine converge in this logic.

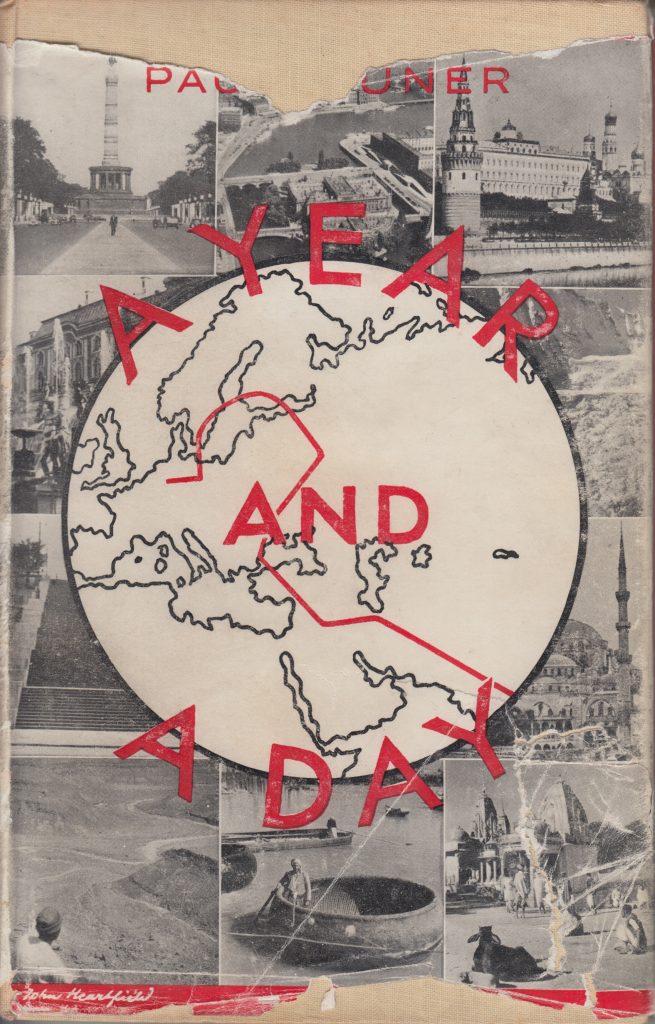

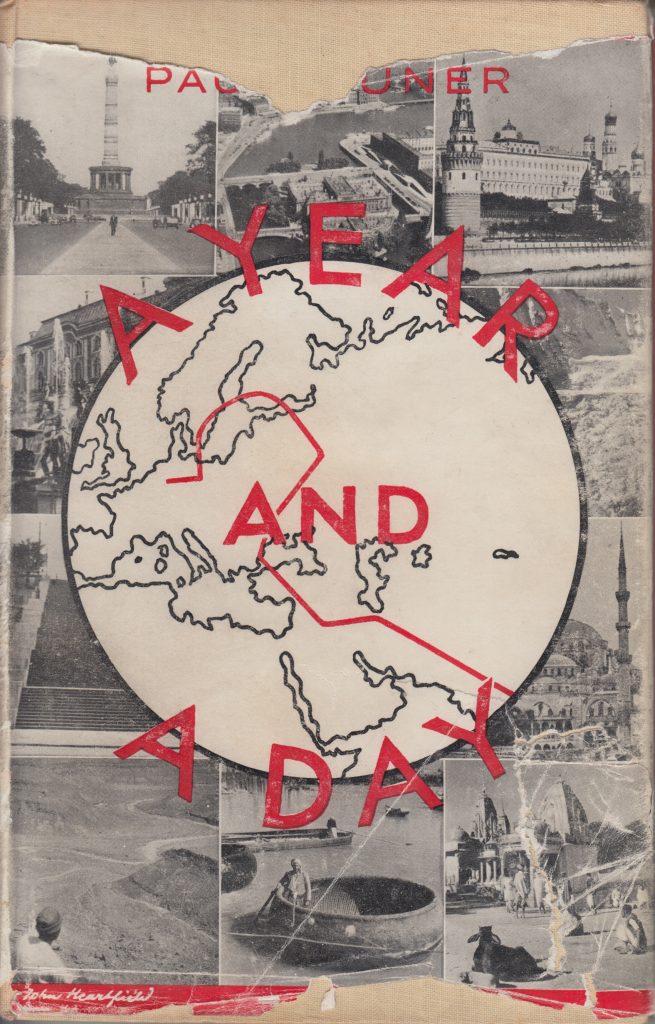

Fig. 06: Paul Duner. A Year and a Day. London: Lindsay Drummond, 1942 , cover design by John Hearfield (Archive Burcu Dogramaci, © The Heartfield Community of Heirs / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023).

by Paul Duner (1942, fig. 6), on the other hand, is dedicated to the author's escape from occupied Belgium in October 1940 and the subsequent passage until his arrival in England in October 1941. Heartfield, who signed the cover with his name, juxtaposed photographs from the countries on Duner’s escape route to form a mosaic. On it is a circular map, with Paul Duner’s route into exile drawn in red. Heartfield's work for Lindsay Drummond in particular contradicts the view widely held by art historians that the artist was less noticed in English exile because his work was too modern or radical.

[30] That view ignores the fact that the book, like the magazine, was a mobile medium that was bought, read, shared and mailed. Even during the Second World War alone, Lindsay Drummond published 157 books, many of which were designed by Heartfield.

[31] Heartfield’s work for the publisher gave him visibility and allowed his work to circulate in the public domain, often with Heartfield’s signature on the covers.

[32] Heartfield’s last published work for Lindsay Drummond dates to 1949, and he relocated to East Germany a year later.

[33] Though all too often devalued in the literature as him just earning a paycheque, Heartfield cherished his work for Lindsay Drummond, as proven by the many framed covers and motifs adorning the walls of his Berlin flat in Friedrichstraße after his remigration.

[34]

Dis:connected objects and actors: reframing exile history

Lili Körber’s book

Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag thus opens up two exile stories that stand for dispersion, dislocation and new beginnings. Although the book fell victim to Nazi book burning and was confiscated from German libraries, a few copies can still be found in used-book shops. My search was also successful, even ending in a rare copy with a preserved dust jacket. By the way, Lili Körber carried the book with her on her various exile stops. When Gabriele Kreis visited her in New York in May 1980, Körber showed her a copy of

Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag, but distanced herself from the book because her view of the Soviet Union had long since changed.

[35] In a questionnaire sent to emigrant writers in 1959 by the publicist Wilhelm Sternfeld, Körber listed her book

Eine Jüdin erlebt das neue Deutschland (1934) as her first publication.

[36] She had thus broken with her burnt first work during her exile.

Incidentally,

Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag can also be found in John Heartfield’s estate.

[37] The artist thus took it into exile and carried the book with him when he remigrated to the SBZ. This makes it a book with its own history of exile, a moving object, reproductions of which have been repeatedly shown in reproduction at various exhibitions in recent years as part of Annette Kelm's work

Die Bücher (2019/20).

In conclusion, this also allows us to reflect on the connective and dis:connective. Lili Körber’s book

Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag is connected to the publication landscape of the Weimar Republic, to the book burnings in National Socialism (and thus denied literary reception in Germany after 1933 and from 1938 onwards in Austria) and to histories of emigration. It is disconnected, though, from the local literary landscape in New York and London, because Körber’s books were not known there and were not available in translation. The book is connected to two actors who remained unconnected/dis:connected due to their global dispersion. Annette Kelm, in turn, has reacquainted the contemporary art scene and a contemporary art audience with

Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag –- an audience that gains its own access to the dis:connected objects through Kelm’s photographic conceptual art.

[38]

[1] On such

verbrennungswürdiger Bücher, see: Angela Graf, ‘April/Mai 1933 — Die “Aktion wider den undeutschen Geist” und die Bücherverbrennungen, 9–22. Bonn: Bibliothek der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2003’, in

Verbrannt, geraubt, gerettet! Bücherverbrennungen in Deutschland. Eine Ausstellung der Bibliothek der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung anlässlich des 70. Jahrestages (Bonn: Bibliothek der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2003), 12. All translations from German are by the author.

[2] The project was produced in 2019 as part of the exhibition

Tell me yesterday tomorrow at the NS-Dokumentationszentrum, Munich. Cf.: Udo Kittelmann, Nicolaus Schafhausen, and Mirjam Zadoff, ‘Probleme in die Zukunft retten’, in

Annette Kelm – Die Bücher, ed. Udo Kittelmann, Nicolaus Schafhausen, and Mirjam Zadoff (Cologne: Buchhandlung Walther und Franz König, 2022), 139–40.

[3] Robert Kehl, ‘Überlebende Bücher’, Texte zur Kunst, 28 August 2020, https://www.textezurkunst.de/articles/robert-kehl-uberlebende-bucher/; see also: Jan-Holger Kirsch, ‘“Das Buch wird Bild”. Annette Kelms Fotoausstellung “Die Bücher” im Museum Frieder Burda, Salon Berlin’, Visual History, 17 August 2020, https://visual-history.de/2020/08/17/das-buch-wird-bild/.

[4] Robert Kehl, ‘Überlebende Bücher’.

[5] Cf.: Walter Fähnders, ‘Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag. Lili Körbers Tagebuch-Roman über die Putilow-Werke’, in

Der lange Schatten des ‘Roten Oktober’. Zur Relevanz und Rezeption sowjet-russischer Literatur in Österreich 1918–1938, ed. Primus-Heinz Kucher and Rebecca Unterberger, Wechselwirkungen. Österreichische Literatur im internationalen Kontext, 22 (Berlin: Peter Lang, 2019), 118–19.

[6] Viktoria Hertling,

Quer durch: Von Dwinger bis Kisch: Berichte und Reportagen über die Sowjetunion aus der Epoche der Weimarer Republik (Königstein: Forum Academicum, 1982), 95.

[7] Siegfried Kracauer, ‘Aus dem roten Alltag’,

Frankfurter Zeitung, 24 July 1932, 2. Morgenblatt, 5; see also: Fähnders, ‘Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag’, 120; Hertling,

Quer durch, 93.

[8] The book has also been translated into English, Bulgarian and Japanese. Cf.: Viktoria Hertling, ‘Nachwort’, in

Eine Österreicherin erlebt den Anschluss, by Lili Körber (Vienna: Christian Brandstätter, 1988), 151–57.

[9] Cf.: Fähnders,

Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag, 122–23.

[10] Lili Körber,

Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag (Rowohlt, 1932), Blurb.

[11] Cf.: Hertling, ,

Quer durch, 96.

[12] Vera Chiquet,

Fake Fotos. John Heartfields Fotomontagen in populären Illustrierten, Edition Medienwissenschaft, 47 (Bielefeld: Transcipt Verlag, 2018), 19.

[13] On the book covers see above all: Lux Rettej,

John Heartfield. Buchgestaltung und Fotomontage. Eine Sammlung, ed. Friedrich Haufe (Berlin: Rotes Antiquariat and Galerie C. Bartsch, 2014). On the website

https://heartfield.adk.de all book covers kept in the estate are available, often also different versions.

[14] Chiquet,

Fake Fotos, 123.

[15] Hertling, ‘Nachwort’, 154; Lili Körber,

Eine Jüdin erlebt das neue Deutschland (Vienna: Verlag der Buchhandlung Richard Lanyi, 1934).

[16] Reichsschrifttumskammer, ed.,

Liste 1 des schädlichen und unerwünschten Schrifttums. Gemäß §1 der Anordnung des Präsidenten der Reichsschrifttumskammer vom 25. April 1935. (Berlin: Reichsdruckerei, 1935), 67, https://digitale-sammlungen.ulb.uni-bonn.de/periodical/pageview/6670278.

[17] ‘Bibliothek verbrannter Bücher’, accessed 13 February 2023.

http://www.verbrannte-buecher.de/.

[18] Gabriele Kreis, ‘Lili Körber. Leben und Werk’, in

Die Ehe der Ruth Gomperz. Roman, by Lili Körber (Mannheim: Persona, 1984), 10.

[19] For a description of route Lili Körber and her partner Erich Grave took into exile, see: Viktoria Hertling, ‘Farewell to Yesterday. Lili Körbers Exil in New York zwischen Fiktion und Wirklichkeit’,

Dachauer Hefte. Special Issue ‘Überleben und Spätfolgen’ 8, no. 8 (1992): 205–7.

[20] I thank Silke Wehrle for making this serial novel accessible to me.

[21] Cf.: Hertling, ‘Farewell to Yesterday’, 208.

[22] Christiana Puschak, ‘Eine von ihnen. Auf Entdeckungsfahrt in die Wirklichkeit. Vor 125 Jahren wurde Lili Körber geboren’, Junge Welt, https://www.jungewelt.de/artikel/print.php?id=421489. Accessed April, 2023.

[23] Lili Körber,

Die Ehe der Ruth Gomperz (Mannheim: Persona, 1984); Lili Körber,

Eine Österreicherin erlebt den Anschluß (Vienna: Brandstätter, 1988).

[24] See: Hertling,

Quer durch; Herta Wolf, ‘Lili Körber. Eine Emigration in die Vergessenheit’, in

Eine schwierige Heimkehr. Österreichische Literatur im Exil 1939–1945, ed. Johann Holzner, Sigurd Paul Scheichl and Wolfgang Wiesmüller (Innsbruck: Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Kulturwissenschaft, 1991), 285–298; Fähnders,

Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag; Katharina Schätz,

Alltag im Arbeiterviertel. österreichisch-russische Tagebuchrealitäten bei Alja Rachmanowa und Lili Körber (Vienna: Paesens Verlag, 2019).

[25] Cf.: Fähnders, ‘Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag’, 121. See also: Matthias Heeke,

Reise zu den Sowjets. Der ausländische Tourismus in Russland 1921–1941. Mit einem bio-bibliographischen Anhang zu 96 deutschen Reiseautoren (Münster et al.: LIT Verlag, 2003), 561–637.

[26] Wolf, ‘Lili Körber’, 285–298.

[27] Gabriele Kreis, ‘”Schreiben aus eigener Erfahrung...” Drei Schriftstellerinnen im Exil: Lili Körber, Irmgard Keun, Adrienne Thomas’, in

Zwischen Aufbruch und Verfolgung. Künstlerinnen der zwanziger und dreißiger Jahre, ed. Denny Hirschbach and Sonia Nowoselsky (Bremen: Zeichen+Spuren, 1993), 67–71.

[28] Anna Schultz, ‘Uncompromising Mimicry. Heartfield’s Exile in London’, in

John Heartfield. Photography Plus Dynamyte, ed. Angela Lammert, Rosa von der Schulenburg, and Anna Schultz (Exh. Cat. Akademie der Künste, 2020), 76–71. For John Heartfield’s work in London, see also: Burcu Dogramaci, ‘John Heartfield’,

Metromod, . accessed 14 February, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5138-9615821

[29] The exiled Norwegian historian Jacob S. Worm-Müller published

Norway revolts against the Nazis (1941, 2nd ed.) with Lindsay Drummond. The Austrian writer Felix Langer, who had lived in exile in London since 1939, published

Stepping Stones to Peace. On the problems of post-war relations with Germany (1943).

The volume The Future of the Jews was edited by J. J. Lynx in 1945.

[30] See among others: Jutta Vinzent,

Identity and Image. Refugee Artists from Nazi Germany in Britain (1933–1945), Schriften der Guernica-Gesellschaft, 16 (Weimar: VDG, 2006), 134; Barbara Copeland Buenger, ‘John Heartfield in London. 1938–45’, in

Exil. Flucht und Emigration europäischer Künstler 1933–1945, ed. Stepahnie Barron and Sabine Eckmann (Munich: Prestel, 1997), 74.

[31] See entries in the catalogue of British Library:

http://explore.bl.uk/, accessed 14 February 2023.

[32] Anna Schultz writes in ‘Uncompromising Mimicry. Heartfield’s Exile in London’, 197: ‘The firm’s (Lindsay Drummond) directors clearly wished to capitalize on Heartfield’s reputation, and his name was prominently displayed on the covers he designed.’

[33] Almost no information can be found about Drummond. On the one hand, it is said that he founded his publishing house in 1938 and died in 1949: John Krygier, ‘Russian Literature Library’, A Series of a Series: 20th-Century Publishers Book Series, accessed 14 February 2023, https://seriesofseries. owu.edu/russian-literature-library/. On the Wikipedia entry of his father, see ‘Laurence Drummond’, Wikipedia, accessed 14 February 2023, https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laurence_Drummond.

[34] Anna Schultz, ‘Uncompromising Mimicry’, 202, footnote 23.

[35] Gabriele Kreis, ‘Lili Körber. Leben und Werk’, 7.

[36]Ibid., 7.

[37] See

https://heartfield.adk.de/node/4466, accessed 14 February 2023.

[38] This research on John Heartfield was conducted with the support of the author’s ERC Consolidator Grant project ‘Relocating Modernism: Global Metropolises, Modern Art and Exile (METROMOD)’ (European Research Council (ERC) under the Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, 2016), grant agreement No 724649 – METROMOD.

bibliography:

Akademie der Künste, ‘Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag: Ein Tagebuchroman aus den Putilovwerken’, Heartfield online. Accessed 14 February 2023. https:// heartfield.adk.de/node/4466.

‘Bibliothek verbrannter Bücher’. Accessed 13 February 2023. http://www. verbrannte-buecher.de/.

British Library, ‘Explore the British Library’. Accessed 14 February 2023. http:// explore.bl.uk/.

Chiquet, Vera.

Fake Fotos. John Heartfields Fotomontagen in populären Illustrierten. Edition Medienwissenschaft, 47. Bielefeld: Transcipt Verlag, 2018.

Copeland Buenger, Barbara. ‘John Heartfield in London. 1938–45’. In Exil. Flucht und Emigration europäischer Künstler 1933–1945, edited by Stephanie Barron and Sabine Eckmann, 74–79. Munich: Prestel, 1997

Dogramaci, Burcu. ‘John Heartfield’.

Metromod, 20 June 2021.

https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5138-9615821.

Fähnders, Walter. ‘Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag. Lili Körbers Tagebuch-Roman über die Putilow-Werke’. In

Der lange Schatten des ‘Roten Oktober’. Zur Relevanz und Rezeption sowjet-russischer Literatur in Österreich 1918–1938, edited by Primus-Heinz Kucher and Rebecca Unterberger, Wechselwirkungen. Österreichische Literatur im internationalen Kontext, 22., 117–32. Berlin: Peter Lang, 2019.

Graf, Angela. ‘April/Mai 1933 – Die “Aktion wider den undeutschen Geist” und die Bücherverbrennungen , 9–22. Bonn: Bibliothek Der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2003.’ In

Verbrannt, geraubt, gerettet! Bücherverbrennungen in Deutschland. Eine Ausstellung der Bibliothek der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung anlässlich des 70. Jahrestages, 9–22. Bonn: Bibliothek der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2003.

Heeke, Matthias.

Reise zu den Sowjets. Der ausländische Tourismus in Russland 1921–1941. Mit einem bio-bibliographischen Anhang zu 96 deutschen Reiseautoren. Münster et al.: LIT Verlag, 2003.

Hertling, Viktoria. ‘Farewell to Yesterday. Lili Körbers Exil in New York zwischen Fiktion und Wirklichkeit’.

Dachauer Hefte. Special Issue ‘Überleben und Spätfolgen’ 8, no. 8 (1992): 202–12.

———. ‘Nachwort’. In

Eine Österreicherin erlebt den Anschluss, by Lili Körber, 151–57. Vienna: Christian Brandstätter, 1988.

———.

Quer durch: Von Dwinger Bis Kisch: Berichte und Reportagen über die Sowjetunion aus der Epoche der Weimarer Republik. Königstein: Forum Academicum, 1982.

Kehl, Robert. ‘Überlebende Bücher’.

Texte zur Kunst, 28 August 2020. https://www.textezurkunst.de/articles/robert-kehl-uberlebende-bucher/.

Kirsch, Jan-Holger. ‘“Das Buch wird Bild”. Annette Kelms Fotoausstellung “Die Bücher” im Museum Frieder Burda, Salon Berlin’. Visual History, 17 August 2020.

https://visual-history.de/2020/08/17/das-buch-wird-bild/.

Kittelmann, Udo, Nicolaus Schafhausen, and Mirjam Zadoff. ‘Probleme in die Zukunft retten’. In

Annette Kelm – Die Bücher, edited by Udo Kittelmann, Nicolaus Schafhausen, and Mirjam Zadoff, 139–40. Cologne: Buchhandlung Walther und Franz König, 2022.

Körber, Lili. Begegnungen im Fernen Osten. Budapest: Biblios publishers, 1936.

———. Die Ehe der Ruth Gomperz. Mannheim: Persona, 1984.

———. Eine Frau erlebt den roten Alltag. Rowohlt, 1932.

———. Eine Jüdin erlebt das neue Deutschland. Vienna: Verlag der Buchhandlung Richard Lanyi, 1934.

———. Eine Österreicherin erlebt den Anschluß. Vienna: Brandstätter, 1988.

Kracauer, Siegfried. ‘Aus dem roten Alltag’. Frankfurter Zeitung, 24 July 1932, 2. Morgenblatt.

Kreis, Gabriele. ‘Lili Körber. Leben und Werk’. In

Die Ehe der Ruth Gomperz. Roman., by Lili Körber, 5–13. Mannheim: Persona, 1984.

———. ‘”Schreiben aus eigener Erfahrung...” Drei Schriftstellerinnen im Exil: Lili Körber, Irmgard Keun, Adrienne Thomas’. In

Zwischen Aufbruch und Verfolgung. Künstlerinnen der zwanziger und dreißiger Jahre, edited by Denny Hirschbach and Sonia Nowoselsky, 65–80. Bremen: Zeichen+Spuren, 1993.

Puschak, Christiana. ‘Eine von ihnen. Auf Entdeckungsfahrt in die Wirklichkeit. Vor 125 Jahren wurde Lili Körber geboren’. Junge Welt, 25 February 2022.

https://www.jungewelt.de/artikel/print.php?id=421489.

Reichsschrifttumskammer, ed.

Liste 1 des schädlichen und unerwünschten Schrifttums. Gemäß §1 der Anordnung des Präsidenten der Reichsschrifttumskammer vom 25. April 1935. Berlin: Reichsdruckerei, 1935. https://digitale-sammlungen.ulb.uni-bonn.de/periodical/pageview/6670278.

Rettej, Lux.

John Heartfield. Buchgestaltung und Fotomontage. Eine Sammlung. Edited by Friedrich Haufe. Berlin: Rotes Antiquariat and Galerie C. Bartsch, 2014.

Schätz, Katharina.

Alltag Im Arbeiterviertel. Österreichisch-russische Tagebuchrealitäten bei Alja Rachmanowa und Lili Körber. Vienna: Paesens Verlag, 2019.

Schultz, Anna. ‘Uncompromising Mimicry. Heartfield’s Exile in London’. In

John Heartfield. Photography Plus Dynamyte, edited by Angela Lammert, Rosa von der Schulenburg, and Anna Schultz, 194–202. Exh. Cat. Akademie der Künste, 2020.

Vinzent, Jutta.

Identity and Image. Refugee Artists from Nazi Germany in Britain (1933–1945). Schriften der Guernica-Gesellschaft, 16. Weimar: VDG, 2006.

Wolf, Herta. ‘Lili Körber. Eine Emigration in die Vergessenheit’. In

Eine schwierige Heimkehr. Österreichische Literatur im Exil 1939–1945, edited by Johann Holzner, Sigurd Paul Scheichl, and Wolfgang Wiesmüller, 285–98. Innsbruck: Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Kulturwissenschaft, 1991.

citation information:

Dogramaci, Burcu. ‘Eine Frau Erlebt Den Roten Alltag, Written by Lili Körber and Designed by John Heartfield (Cover): Burnt Books, Exiled Authors and Dis:Connective Memories’. Global Dis:Connect Blog (blog), 30 May 2023. https://www.globaldisconnect.org/05/30/exiled-authors-and-disconnected-memories/.

Continue Reading

My academic interests are broad, ranging from history, German and English to pedagogy, but I enjoy working on ancient history the most. My research focuses on the history of the everyday and social history of the Roman Empire in late antiquity. So far, I have worked on the communicative power of clothing, fashion and outward appearance in Roman life and on the spread of Christianity through Sicily in late antiquity. I really enjoy this subfield, as I get to explore the details that formed ancient people’s identity and to some extent bridge the gap to people who seem so far away from today’s reality.

What tasks do you handle at global dis:connect, and what do you enjoy the most?

Apart from assisting our fellows and team members, I savor working in gd:c’s dissemination efforts as a content creator and PR advisor for social media. My biggest passion and best capability is loving things of any kind deeply and, most importantly, sharing the things I love deeply with other people. At gd:c I get to share the very essence of our institute via words, photographs and videos, which I cherish.

What’s your credo and why?

Per aspera ad astra. An ancient saying my beloved and very inspiring Latin teacher taught me. It reminds me what I am capable of and where I can go — ad astra. At the same time, it expresses what you have to go through to get to the stars — per aspera. Work hard and truly believe in your yourself to overcome any limit. It might be cheesy, but it has proven to be true.

My academic interests are broad, ranging from history, German and English to pedagogy, but I enjoy working on ancient history the most. My research focuses on the history of the everyday and social history of the Roman Empire in late antiquity. So far, I have worked on the communicative power of clothing, fashion and outward appearance in Roman life and on the spread of Christianity through Sicily in late antiquity. I really enjoy this subfield, as I get to explore the details that formed ancient people’s identity and to some extent bridge the gap to people who seem so far away from today’s reality.

What tasks do you handle at global dis:connect, and what do you enjoy the most?

Apart from assisting our fellows and team members, I savor working in gd:c’s dissemination efforts as a content creator and PR advisor for social media. My biggest passion and best capability is loving things of any kind deeply and, most importantly, sharing the things I love deeply with other people. At gd:c I get to share the very essence of our institute via words, photographs and videos, which I cherish.

What’s your credo and why?

Per aspera ad astra. An ancient saying my beloved and very inspiring Latin teacher taught me. It reminds me what I am capable of and where I can go — ad astra. At the same time, it expresses what you have to go through to get to the stars — per aspera. Work hard and truly believe in your yourself to overcome any limit. It might be cheesy, but it has proven to be true.

What tasks do you handle at global dis:connect, and what do you enjoy the most?

At global dis:connect, my responsibilities primarily revolve around supporting the planning and execution of events, which involves tasks like coordinating logistics, managing communications and ensuring everything runs smoothly on the day of the event. What I find most enjoyable is the opportunity to work closely with a team, brainstorming ideas, problem-solving together and ultimately seeing our efforts come to life in successful events.

Would you like to have photographic memory and why?

Having a photographic memory would indeed be advantageous, especially for tasks like rapidly absorbing and synthesising a lot of literature, which would be incredibly useful for my upcoming bachelor's thesis. Additionally, having instant-recall abilities would make me the ultimate walking encyclopaedia ready to amaze everyone with facts at any given moment!

Who is your favourite character from a novel or film and why?

Treebeard from J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings.

As one of the Ents, guardians of the forests, Treebeard personifies nature's voice and symbolises resistance against the destructive forces of human evil. While he seems too slow and deliberate in the beginning to achieve anything, he later transforms into a leader determined to save Middle Earth. I also love his deep understanding of the world and its history.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R1njDtvLIoA

What tasks do you handle at global dis:connect, and what do you enjoy the most?

At global dis:connect, my responsibilities primarily revolve around supporting the planning and execution of events, which involves tasks like coordinating logistics, managing communications and ensuring everything runs smoothly on the day of the event. What I find most enjoyable is the opportunity to work closely with a team, brainstorming ideas, problem-solving together and ultimately seeing our efforts come to life in successful events.

Would you like to have photographic memory and why?

Having a photographic memory would indeed be advantageous, especially for tasks like rapidly absorbing and synthesising a lot of literature, which would be incredibly useful for my upcoming bachelor's thesis. Additionally, having instant-recall abilities would make me the ultimate walking encyclopaedia ready to amaze everyone with facts at any given moment!

Who is your favourite character from a novel or film and why?

Treebeard from J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings.

As one of the Ents, guardians of the forests, Treebeard personifies nature's voice and symbolises resistance against the destructive forces of human evil. While he seems too slow and deliberate in the beginning to achieve anything, he later transforms into a leader determined to save Middle Earth. I also love his deep understanding of the world and its history.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R1njDtvLIoA

At global dis:connect, my primary duty is to design posters and flyers for our workshops. Additionally, I plan and assist with the preparation of these events. What I find most enjoyable is the opportunity to meet fascinating new people during these occasions as well as the creative freedom I have when designing.

What do you define as home and why?

My home isn't a physical location, but a place where my friends and family are. It's a place where I feel at ease, can enjoy wonderful experiences and where time seems to fly by.

What’s your credo and why?

My credo in life is that everything will unfold as it's supposed to. There's no need to overthink things because life has a plan for each of us, regardless of whether we worry or not.

At global dis:connect, my primary duty is to design posters and flyers for our workshops. Additionally, I plan and assist with the preparation of these events. What I find most enjoyable is the opportunity to meet fascinating new people during these occasions as well as the creative freedom I have when designing.

What do you define as home and why?

My home isn't a physical location, but a place where my friends and family are. It's a place where I feel at ease, can enjoy wonderful experiences and where time seems to fly by.

What’s your credo and why?

My credo in life is that everything will unfold as it's supposed to. There's no need to overthink things because life has a plan for each of us, regardless of whether we worry or not.

What aspects of the research at global dis:connect pique your curiosity and how does it overlap with your research?

While globalisation in general is a topic I am extremely interested in, I am especially passionate about migration processes and their impact. Colonisation, the migration connected to it and their effects on society are core topics at global dis:connect, and the impact in particular on past and contemporary literature is a topic I am really interested in.

What do you define as home and why?

To me, home is less a specific place than a feeling thaf is mostly connected to people I feel really comfortable with. Whether it‘s going out and having a couple of drinks, travelling to new countries or just hanging out at home talking about live and joking around, my home is wherever my favourite humans are.

Who is your favourite character from a novel or film and why?

My favourite fictional character would have to be Chandler Bing from the TV show Friends, maybe just because no other person has ever made laugh as hard and feel incredibly connected to them at the same time. His self-deprecating humour and his use of sarcastic comments at every possible opportunity have taught me that it‘s incredibly important not to take life too seriously.

What aspects of the research at global dis:connect pique your curiosity and how does it overlap with your research?

While globalisation in general is a topic I am extremely interested in, I am especially passionate about migration processes and their impact. Colonisation, the migration connected to it and their effects on society are core topics at global dis:connect, and the impact in particular on past and contemporary literature is a topic I am really interested in.

What do you define as home and why?

To me, home is less a specific place than a feeling thaf is mostly connected to people I feel really comfortable with. Whether it‘s going out and having a couple of drinks, travelling to new countries or just hanging out at home talking about live and joking around, my home is wherever my favourite humans are.

Who is your favourite character from a novel or film and why?

My favourite fictional character would have to be Chandler Bing from the TV show Friends, maybe just because no other person has ever made laugh as hard and feel incredibly connected to them at the same time. His self-deprecating humour and his use of sarcastic comments at every possible opportunity have taught me that it‘s incredibly important not to take life too seriously.

What aspects of the research at global dis:connect pique your curiosity and how does it overlap with your research?

What aspects of the research at global dis:connect pique your curiosity and how does it overlap with your research?

What tasks do you handle at global dis:connect, and what do you enjoy the most?

What tasks do you handle at global dis:connect, and what do you enjoy the most?