Tears through the Red Sea

andrea frohne

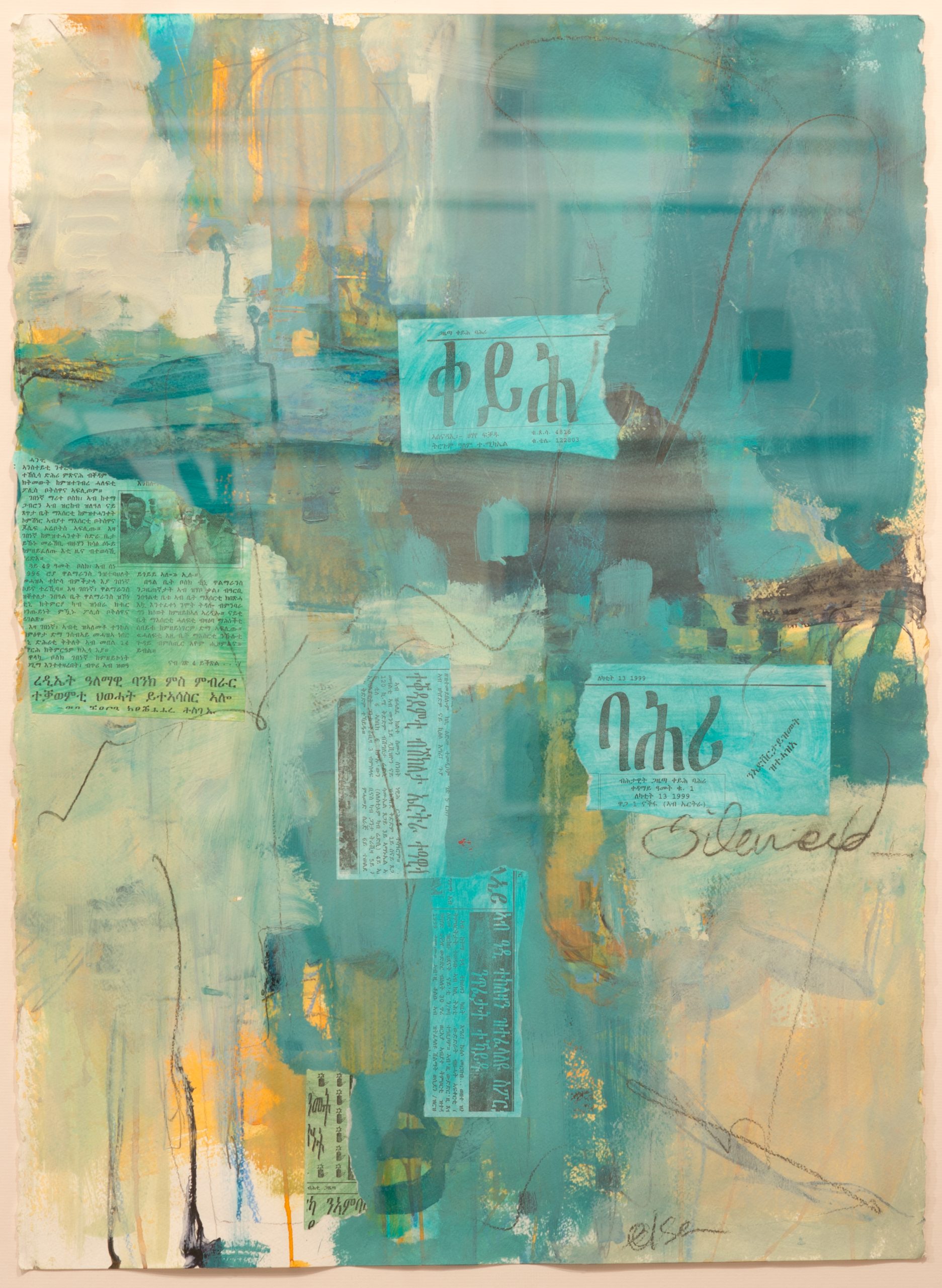

Elsa Gebreyesus (Eritrean, born in Ethiopia, lives in Fairfax, Virginia, USA), Silenced V, 2010, mixed media on paper, 30” x 37”, photograph by Andrea Frohne.

Silenced V contains the front page of the newspaper Red Sea (ቀይሕ ባሕሪ), published between 1997 and 2001 in the Tigrinya language. The blue and green colours across the artwork represent the Red Sea along the coast of Eritrea and the Horn of Africa. Elsa Gebreyesus tore the newspaper’s masthead in half and pasted it onto the canvas.[1] Underneath, she inscribed the word ‘Silenced’. The artwork depicts a rift and disconnection from globalised processes in the country’s political and social fabric resulting from the suppression of free speech and access to information. In addition, the torn newspaper evokes the torn relationships among Red Sea maritime nations in the Horn of Africa. It connected countries through trade and cultural exchange for centuries. Yet the sea has also existed as a site of disconnection and regional conflict.

Born in Ethiopia to an Eritrean family, Elsa Gebreyesus moved at age seven with her family to Kenya during the Ethiopian Revolution. After spending her youth in Kenya, she moved with her parents and siblings to the USA and then to Canada. Elsa Gebreyesus has dislocated or emigrated from homes and then reconnected to new countries five times. The first two departures, out of Ethiopia and Kenya, were from countries that were not native to her. The artist lived in Eritrea following a 30-year war for independence. She worked for five years in the 1990s with a women’s nonprofit organisation in Eritrea and fled prior to a governmental crackdown.

Like many of her generation, Elsa Gebreyesus was caught up in the celebration of Eritrea’s independence from Ethiopia in 1991 after the Eritrean War of Independence, and she decided to move to Eritrea in February 1992, setting foot in the country of her heritage for the first time in her early twenties. Putting her management skills to work, she promoted gender equity for five years at a women’s nonprofit called the National Union of Eritrean Women.[2] Toward the end of her stay, Elsa Gebreyusus witnessed a vibrant free press for a brief time in Eritrea from 1996 until 2001. By 1997, several privately run newspapers would sell out every morning.[3] The atmosphere of freedom and optimism about Eritrea’s future impressed her and informed a series of artworks she developed 15 years later.

By 1997, the government began implementing increasingly repressive measures. Even though in that year, a carefully written and debated new constitution that grew out of the fight for liberation was passed, it remains unimplemented to this day. The exhilaration and possibility of the newly independent Eritrean nation in 1991 had dissipated as another dictator had risen to power: Isaias Afewerki became president in 1993 and remains in power. Since the 1998 Ethiopia-Eritrea border war, the borders of Eritrea have been controlled or closed, with its inhabitants largely prohibited from crossing them. The nation-state’s disconnection from globalised processes is repressive.

Elsa Gebreyesus eventually found it necessary to leave Eritrea in 1997, and she witnessed the continuation of the dictator’s takeover from her new diasporic home in the United States. Inspired by her observation of Eritrea’s free press from 1996 to 2001, she used her art to help her process Eritrea’s change of trajectory toward repression and global disconnection.

The path to dictatorship in Eritrea occurred in a series of stages, reaching a culmination in 2001. The September 2001 state crackdown effectively distanced Eritrea from transnational processes, and it continues to this day. From the United States, Elsa Gebreyesus watched closely and anxiously as all independent newspapers in Eritrea were abolished, and all captured journalists were imprisoned in one fell swoop.[4] To this day, no one knows where they are imprisoned or whether they are alive or dead. The Guardian profiled each journalist in 2015 in a world-news article.[5]

In contrast to the state newspaper, Elsa Gebreyesus’s collaged newspaper fragments for the Silenced series are from the independent, privately owned papers that existed in newly independent Eritrea during the few years of press freedom. The artist selected sections of newspapers with dates in order to mark the national liberatory moment, and she also chose articles related to mundane aspects of life.[6] The latter includes, for example, a bicycle race in Silenced V. Yet even such innocuous words have in effect been censored since these newspapers are not housed in libraries and institutional archives. The copies the artist used were smuggled out of Eritrea and given to her in the diaspora. Elsa Gebreyesus’s artworks reconnect the memory of these newspapers to her new African diaspora. It is only from her position in a diaspora that she possesses the ability to narrate this history. The disconnection or tear through the Red Sea produces tears of sorrow for many reasons. Yet within the artwork, the small pieces of newspaper remind us of the freedom to write.

[1] The naming tradition in Eritrea is to refer to a person by their first name. The surname is simply the first name of the person’s father. Because it would be awkward to refer to my artist as Elsa only, I take the naming convention that scholars follow, which is to always write the first and last name of the artist. So in my text, you will see ‘Elsa Gebreyesus’ throughout.

[2] Elsa Gebreyesus, Telephone Interview with Andrea Frohne, 2 December 2015.

[3] Gebreyesus.

[4] European Asylum Support Office, EASO Country of Origin Information Report: Eritrea : Country Focus (Luxembourg: Publications Office, 2015), 22, https://www.easo.europa.eu/news-events/easo-issues-country-origin-information-report-eritrea-country-focus. Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in Eritrea; Report of the detailed findings of the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in Eritrea. United Nations Human Rights Council (Geneva: 5 June 2015). https://www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/hrc/co-i-eritrea/report-co-i-eritrea-0. A principal finding of the United Nations commission is that, ‘[F]ollowing the 2001 crackdown, there has not been any press freedom in Eritrea. At that moment, the Eritrean Government suppressed the emerging free press by closing down independent newspapers and silenced journalists by arresting, detaining, torturing and having them disappeared’ (148).

[5] Abraham T. Zere, ‘“If We Don’t Give Them a Voice, No One Will”: Eritrea’s Forgotten Journalists, Still Jailed after 14 Years’, The Guardian, 19 August 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/aug/19/eritrea-forgotten-journalists-jailed-pen-international-press-freedom. Abraham Zere is a journalist who publishes articles about Eritrea from beyond its borders.

[6] Gebreyesus, Telephone interview with Andrea Frohne.

Bibliography

European Asylum Support Office. EASO Country of Origin Information Report: Eritrea : Country Focus. Luxembourg: Publications Office, 2015. https://www.easo.europa.eu/news-events/easo-issues-country-origin-information-report-eritrea-country-focus.

Gebreyesus, Elsa. Telephone Interview with Andrea Frohne, 2 December 2015.

European Asylum Support Office. EASO Country of Origin Information Report: Eritrea : Country Focus. Luxembourg: Publications Office, 2015. https://www.easo.europa.eu/news-events/easo-issues-country-origin-information-report-eritrea-country-focus.

Gebreyesus, Elsa. Telephone Interview with Andrea Frohne, 2 December 2015.

Report of the detailed findings of the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in Eritrea. United Nations Human Rights Council (Geneva: 5 June 2015). https://www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/hrc/co-i-eritrea/report-co-i-eritrea-0

Zere, Abraham T. ‘“If We Don’t Give Them a Voice, No One Will”: Eritrea’s Forgotten Journalists, Still Jailed after 14 Years’. The Guardian, 19 August 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/aug/19/eritrea-forgotten-journalists-jailed-pen-international-press-freedom.