Dear Tutu: a letter by Palestinian artist Vladimir Tamari on exile, friendship and globalisation

nadia von maltzahn

Dear Tutu,

Hello! How are you. At home your letter is hidden under a pile of books, papers, tools & a thousand other things — in our unconditioned house my desk which faces southish is too hot to work at — so I’m writing in this dubious oasis of Western civilization. It is cool & predictable & has a non-smoking floor, — also soft Hawaiian music — did you read Melville’s “Typee” on south sea island — at that (mid 19th c.) time Hawaii was known as the Sandwich islands & its destruction culturally was well underway — it’s all heartrending in a way because Palestine too was a kind of primeval lagoon forgotten for a few centuries by history (Napoleon in Jaffa does not count, too brief!) Your absent-minded & hurried letter was welcome — glad all my vague & precious fulminations about the state of my life & art slid over your head. Let me restate it in simpler terms. I’m too scared, broke, lazy, confused & perhaps am unable to move from this tinsel & transistor paradise where I’ve very uncomfortably & awkwardly parked![1]

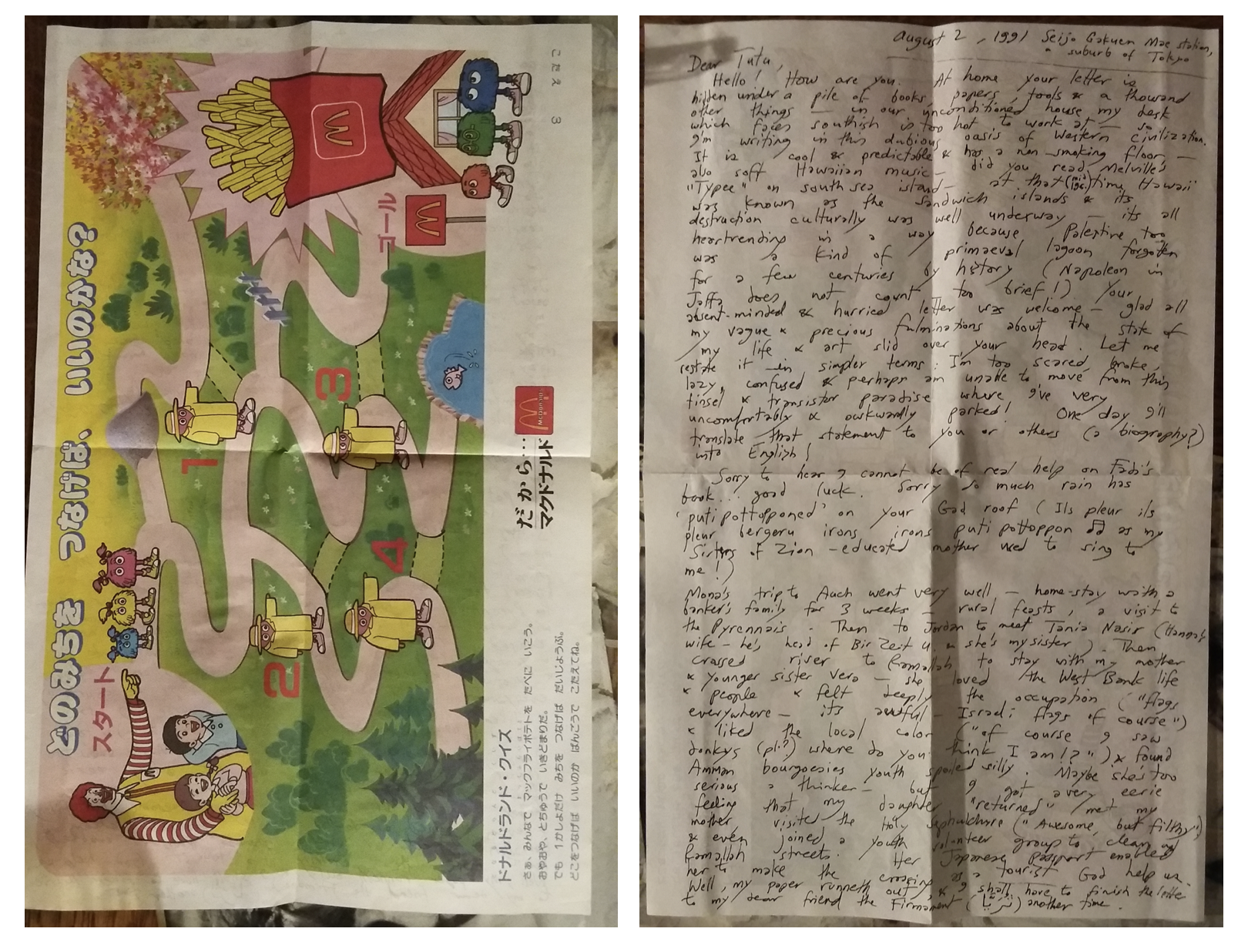

This is how the Tokyo-based Palestinian artist Vladimir Tamari (1942-2017) starts his letter to his friend Tutu, aka Soraya Antonius (1932-2017), who was in Normandy at the time. Written over several days between 2 and 13 August 1991 in suburban Tokyo from a McDonald’s, using a branded paper placemat as stationery for the opening page, the letter addresses questions of exile, friendship and globalisation (figure 1). It demonstrates what ephemera such as this correspondence can teach us about networks, relationships and dis:connectivities in the frame of artistic production.

Fig. 1: Vladimir Tamari: Letter to Tutu, 2 August 1991, cover page recto and verso.

Dis:connectivities here denote the contextual connections and ruptures in which artists create. Dis:connectivity also relates to physical ephemera, their locations, accessibility, fragility, languages and the references they contain. Tamari’s letter could easily have been lost to oblivion, and it has only surfaced by chance.[2]

Here the questions arise: what role do ephemera such as this letter play in (art) history? Who should be responsible for preserving them? Should they be considered private objects that belong in private archives?[3] Or should they be archived as part of an artist’s biography and trajectory — classifiable scientific objects? These are questions we are dealing with in the LAWHA research project (Lebanon’s Art World at Home and Abroad), which investigates the trajectories of artists and their works in and from Lebanon since 1943.[4] Let us examine Vladimir Tamari and his letter to Tutu as a case in point.

The artist: cultural references and networks

Who was Vladimir Tamari? In an autobiographical essay published in the same year as the letter, Tamari describes himself as a Palestinian Arab artist, inventor and physicist, born 1942 in Jerusalem and educated at a Quaker school in his hometown of Ramallah, before studying physics and art at the American University of Beirut. He completed his formal education at Saint Martin’s School of Art in London and the Pendle Hill Center of Study and Contemplation, a Quaker institution near Philadelphia. Between 1966 and 1970 he worked with the United Nations in Beirut until he moved with his Japanese wife to Tokyo, where he lived and worked until his death in 2017.

In the essay, he emphasises four main influences on his thinking:

- church life and rituals (coming from an Orthodox Christian family),

- the culture of Islam that surrounded him in Ramallah and Jerusalem,

- Palestinian and Arab nationalism and

- what he calls ‘a veneer of European “modern” culture and values’.[5]

The cultural references Tamari makes in his letter to Tutu recall these influences. He speaks of the ‘Christian concept of suffering’, the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and the ascetic St Simeon in Northern Syria. The impact of European ‘modern’ culture and history on his writing is obvious, with references to d’Artagnan, Pablo Picasso, Napoleon, William Wordsworth and Richard Wagner. ‘Global’ classics such as the work of Herman Melville, the Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos and Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace are mentioned in the letter with the same familiarity as the contemporary Palestinian poet and author Mahmoud Darwish, the classical Persian poet and scholar Omar Khayyam and the Lebanese writer Amin Malouf.

While the cultural references and his language — he writes in English — are testament to his Western-oriented missionary education and his cultural environment, the people he mentions in his letter show what social circles he shares with its recipient: his family, closely linked to the intellectual and cultural scene of the West Bank (his sister Tania and her husband Hanna Nasir, long-time president of Ramallah’s Birzeit University; his other sister Vera, also an artist); Jordanian artist and pro-Palestinian activist Mona Saudi (1945-2022), who spent a large part of her life in Beirut; John Carswell (b. 1931), artist and professor of fine arts at the American University of Beirut; Lebanese artist Fadi Barrage (1939-1988), and Yuzo Itagaki, professor of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies at the University of Tokyo and ‘one of those rare individuals who is all friendship & love for one & all’ and ‘has followed closely Palestinian affairs’, whom he wanted to put in touch with Tutu for a potential Japanese translation of her latest novel. The partial reduction of family names to their first letter shows the mutual familiarity of Tamari and Tutu with each other’s networks.

The predictability of globalisation

In Tamari’s life and letter, globalisation is a double-edged sword. It is represented by McDonald’s, which runs through the five-page letter like a red thread. Most notable is the stationery of the first page; Ronald McDonald and the unmistakable golden arches immediately allow one to locate the paper visually, but Tamari also directly references this symbol of globalisation as an expression of Western civilisation. Without initially calling it by name — it needs no further explanation — he dubs it a ‘dubious oasis of Western civilisation’ as well as ‘dubious paradise’. McDonald’s embodies his frustration and tense relationship with the globalised Western world. On the one hand, it is questionable, on the other it is a refuge for him — cool and predictable, he knows what to expect and keeps returning to it.[6]

While global brands are easily found in Japan, this does not translate into an openness to the world. The account of an Egyptian journalist traveling to Japan in 1963 accentuates this disjuncture. He writes that ‘in Japan, one finds all of Europe and all of America. (…) But at the same time, one observes that Japan lives in total isolation. Or rather, it is concerned only with itself and pays almost no attention to the existence of others’.[7] Whereas the first McDonald’s had opened in Japan in 1971, as stated on its official website, the country did not boast a large expat community in the early 1990s. Globalisation in Japan might thus heighten the sense of isolation, as it only provides superficial connectivity. Being a Palestinian in Tokyo was a solitary affair, especially if one was not looking for formal political activism. The Palestine Liberation Office (PLO) operated a Japan office from 1977 to 1995,[8] but having left Beirut for Japan ‘in a spirit of disillusionment’,[9] Tamari limited his pro-Palestinian activities mainly to designing posters on relevant occasions, such as PLO-leader Yasser Arafat’s visit to Japan and the third anniversary of the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacre, with reference to Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[10]

Exile and friendship

In his letter, Tamari openly voices his discomfort with life in exile in Japan. He speaks of being ‘scared, broke, lazy, confused’ and of his wish ‘to compress the 20 years in Japan to a few representative years’.[11] He feels isolated and misses what he calls a ‘community of the faithful’ — a local network of like-minded friends, with whom he can digest the news from his home country (‘For me — in my imaginations, the very news became a pain & I’ve stopped reading magazines & newspapers lest I be offended by yet another word of misunderstanding of our cause or, yet read of another facet of American official stupidity! Without the shield of a “community of the faithful” in which I can quench the flaming darts of the smug West, I feel every barb deep in my bones, so out of a sense of survival I rejected a lot of what I heard of’).[12] He struggles with himself and the skin he was born in, with all the baggage he perceives goes along with being a Palestinian, but he cannot let go of despite his efforts (‘What am I trying to say to you, to myself … nothing perhaps but just another feeble attempt to take off this hair shirt I was born with’).

In this sense, there are clear limitations to his integration in a country in which he has ‘very uncomfortably and awkwardly parked’. At the same time, he sees the irony that his daughter’s Japanese passport allows her to visit his birth town of Jerusalem as a tourist (‘God help us’). Tamari clearly expresses his loneliness and lack of a network of solidarity in Japan.

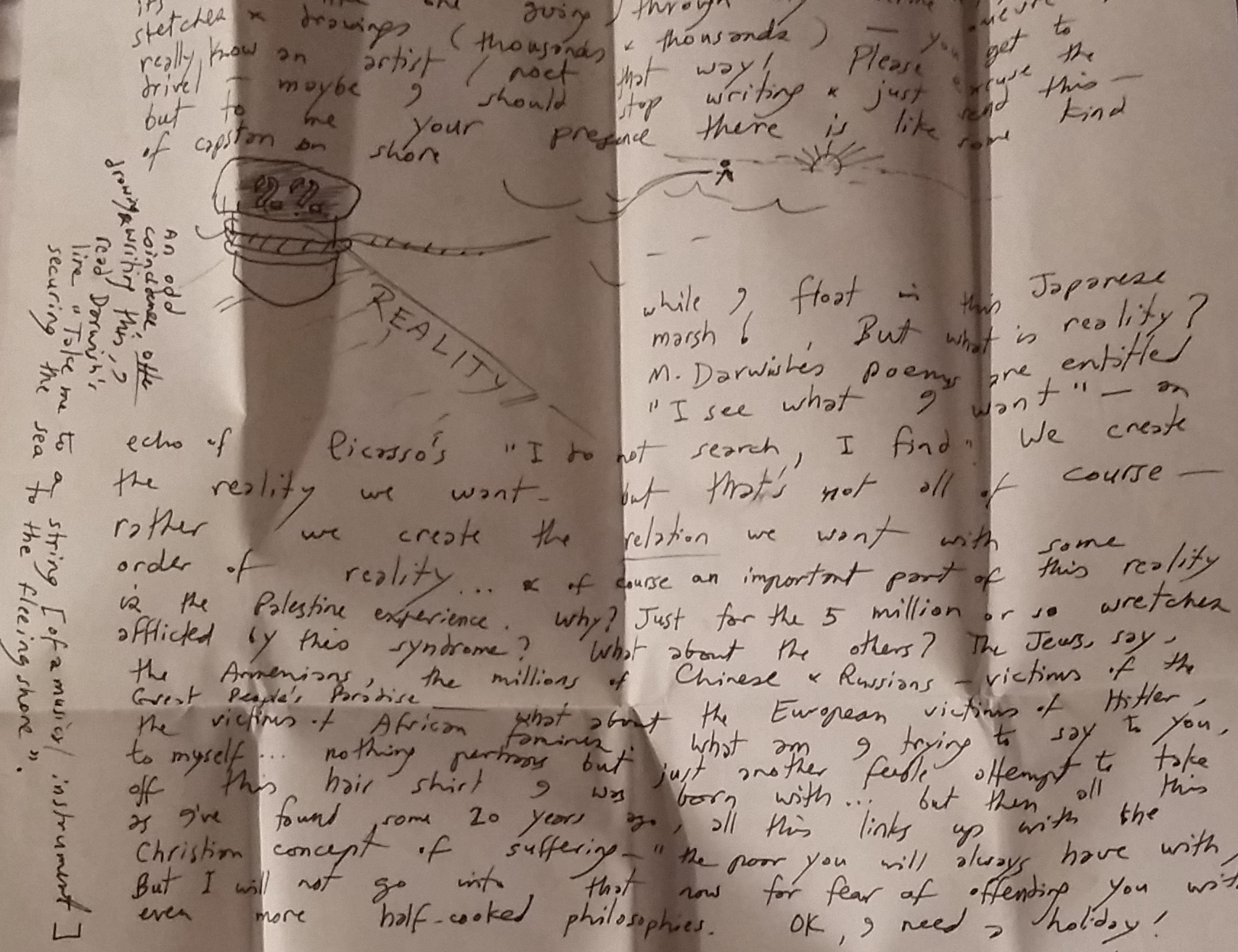

Fig. 2: Vladimir Tamari: Letter to Tutu, 8 August 1991 (excerpt).

Tamari emphasises the importance of a network of likeminded people, even in a globalised world that supposedly facilitates circulation, the role of friendships and a form of continuity that one can rely on (‘you too, too too, have also created a shell of comfort & friendship & silence in your French retreat’), the ‘capstan on shore’ as he refers to Tutu’s presence in France ‘while [he] floats in this Japanese marsh!’ (figure 2). Imagining her in her house in Normandy comforts him in a world in which he perceives many obstacles to friendship. He knows that his addressee understands him and that she is in a similar situation. They share part of their trajectory — like him, she was born in Jerusalem, British-educated and spent a long time in Beirut, where they consolidated their friendship. Both were fighting for the Palestinian cause to varying degrees and were interested in the arts (figure 3). Thus, the correspondence between Vladimir and Tutu presents a form of connectivity that also has its limits. The immediate experience of life in Tokyo can be described, but cannot be lived from a distance. Their friendship helps him to express his loneliness, but not to surpass the perceived and real disconnectivity that separates Tamari from his network and ‘community of the faithful’.

Fig.3: Vladimir Tamari: Poster designed for the Palestinian novelist Soraya Antonius for the exhibition Palestine in Art, London May 1969. (from: The Palestine Poster Project Archives (PPPA), accessible at https://www.palestineposterproject.org/poster/palestine-in-art-catalog-cover)

Being a Palestinian artist in Japan

In his letter, Vladimir Tamari keeps returning to his artistic practice and discloses how he works and archives. He seems to share copies of his artworks with his correspondent regularly, and it is important to him to discuss his technique and the content of his work (‘there is much, technically & thematically, of interest to the discerning observer (you)’). He refers to the quantity of his sketches and drawings (‘thousands & thousands’), through which one can really get to know an artist, and hints at material for a possible biography that could be written one day.

What I find particularly insightful is his description towards the end of the letter about a painting of Jerusalem that he ‘juiced up’, although he considered the simple drawing a better work (‘The other day I made a really nice painting, based on a pencil drawing I probably sent you a copy of — stones roughly arranged to say in Arabic القدس AL-QUDS [Jerusalem] — anyway I juiced it up with color & gold foil, but the pencil drawing remains better’). The subject of much of his oeuvre remained Jerusalem, even after years of exile (figure 4).

Fig. 4: Vladimir Tamari: Arab Jerusalem, 1982, 528 x 728 mm (from: The Palestine Poster Project Archives (PPPA), accessible here https://www.palestineposterproject.org/poster/jerusalem-rock-original-painting)

In this he was not alone, nor in depicting a symbolic version of his hometown. As Makhoul and Hon write about the Palestinian artist and art historian Kamal Boullata, for example, the latter’s representation of Jerusalem as geometric is ‘understandable as an exile’s idealization of a place of origin, but we are left with the feeling that this idealized origin has not only replaced the lost place of his birth but that it also eclipses the present city as a Palestinian urban centre’.[13] Taking this further, the authors suggest that ‘the representation of Jerusalem as a place that can somehow be dislodged from the land, or as a place that is already an image of itself’ is found throughout Palestinian art, exemplified by Sliman Mansour’s Jamal al Mohamel (1973), in which the homeland is being carried as a kind of burden. [14]

This connects back to Tamari’s futile attempts to ‘take off this hair shirt [he] was born with’. While his place of birth remained very present in his art works, the use of bright colours and gold foil that one can see increasingly after he moved to Japan suggests an influence of his surroundings in Japan, a place he refers to as ‘tinsel and transistor paradise’ in his letter. Although he considered the simple version the better work, he felt a need to embellish it.

The role of ephemera in writing art history

The letter reveals a range of connections, connectivities and disconnectivities. It transports the reader into 19th-century Hawaii and Napoleon’s France, takes the author back to Palestine of the 1950s and 1960s, connects to Beirut and Ramallah and testifies to the author’s ambivalent relationship to his place of exile and, on another level, to Western civilisation. It bears witness to the entanglements that Tamari shared with his correspondent, and at the same time it shows the limits of its medium — a letter cannot replace the physical presence of a community of like-minded friends.

Another aspect of the letter as an object relates to its locality and its potential for dis:connectivity. The letter-as-object embodies dis:connectivity in that it can be displaced, lost, found, sent away and travel long distances. It can end up in an archive, where it becomes part of a larger narrative and subject to scholarly investigation if made accessible. Correspondence, diary entries, notebooks, sketches and other ephemera can divulge the context of artistic production and allow us to see the artists and their works in relation to aesthetic and political discourses, personal encounters and their socio-political and cultural surroundings. As this letter has shown, ephemera provide clues to the personal side of artistic production and bridge gaps in our understanding. To conclude in the words of Vladimir Tamari, ‘perhaps human progress may only be measured by how much each one of us can contribute to shorten the distance between two poles’.[15]

[1] Letter from Vladimir Tamari to Soraya Antonius (Tutu), 2-13 August 1991, 5 pages. Private archives, France. All subsequent quotations that are not separately referenced are from this letter.

[2] The letter is part of the collection of Soraya Antonius’s private papers that I manage.

[3] Compare to: Sherene Seikaly, ‘How I Met My Great-Grandfather. Archives and the Writing of History’, CSSAAME 38, no.1 (2018): 6-20.

[4] This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 850760). See https://lawha.hypotheses.org.

[5] Vladimir Tamari, “Influences and Motivations in the Work of a Palestinian Artist/Inventor,” Leonardo 24, no1 (1991): 7-14.

[6] I am grateful to Peggy Levitt, Cresa Pugh, Andreja Siliunas, Kwok Kian Chow and Joanna Jurkiewicz for their precious comments while we looked at this letter collectively as part of the Global (De)Centre platform.

[7] Anis Mansour as quoted in : Alain Roussillon, Identité et Modernité : Les voyageurs égyptiens au Japon (XIXe-XXe siècle (Arles : Actes Sud, 2005), 149. Unless otherwise indicated, all translations are mine.

[8] ‘Japan Palestine Relations (Basic Data)’, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, June 2015, https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/middle_e/palestine/data.html.

[9] Vladimir Tamari, ‘The Birth of the Logo for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine’, Vladimir Tamari, August 2016, http://vladimirtamari.com/pflp-logo.html.

[10] These and other political posters are available from the Palestine Poster Project Archives at https://www.palestineposterproject.org/artist/vladimir-tamari.

[11] Interestingly, he longs for some Polynesian paradise to spend the rest of his life in, rather than wishing to be back in the Middle East.

[12] Like subsequent quotes set in brackets, this quotation comes from Tamari’s letter to Tutu.

[13] Bashir Makhoul and Hon Gordon, The Origins of Palestinian Art (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013), 111. And: Kamal Boullata, Palestinian Art. From 1850 to the Present, London (Saqi, 2009).

[14] Makhoul and Hon, Origins, 115.

[15] Vladimir Tamari, ‘Al-Rasm Bi-l Ab’ad al-Thalatha’ (Drawing in Three Dimensions)’, Mawaqif 16 (1971): 269.

bibliography

Boullata, Kamal. Palestinian Art: From 1850 to the Present. London: Saqi, 2009.

Makhoul, Bashir and Gordon Hon. The Origins of Palestinian Art. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013.

Roussillon, Alain. Identité et Modernité : Les voyageurs égyptiens au Japon (XIXe-XXe siècle. Arles: Actes Sud, 2005.

Seikaly, Sherene. ‘How I Met My Great-Grandfather. Archives and the Writing of History’. CSSAAME 38, no. 1 (2018): 6–20.

Tamari, Vladimir. ‘Al-Rasm Bi-l Ab’ad al-Thalatha’ (Drawing in Three Dimensions)’. Mawaqif 16 (1971): 152–56.

———. ‘Influences and Motivations in the Work of a Palestinian Artist/Inventor’. Leonardo 24, no. 1 (1991): 7–14.

———. ‘The Birth of the Logo for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine’. Vladimir Tamari, August 2016. http://vladimirtamari.com/pflp-logo.html.

citation information

Maltzahn, Nadia von. ‘Dear Tutu: A Letter by Palestinian Artist Vladimir Tamari on Exile, Friendship and Globalisation’. Global Dis:Connect Blog (blog), 13 June 2023. https://www.globaldisconnect.org/06/13/dear-tutu-a-letter-on-exile-friendship-and-globalisation/.