Field surveys, Western modernity and restituted global disconnections

andrea e. frohne

Fig. 01: The juxtaposition of the Kansas wheat field, the imported Afro-Italian cart and Dawit L. Petros’s hands suggests migration, mapping of territory and colonial settlement of the prairies.

Surveying a wheat field

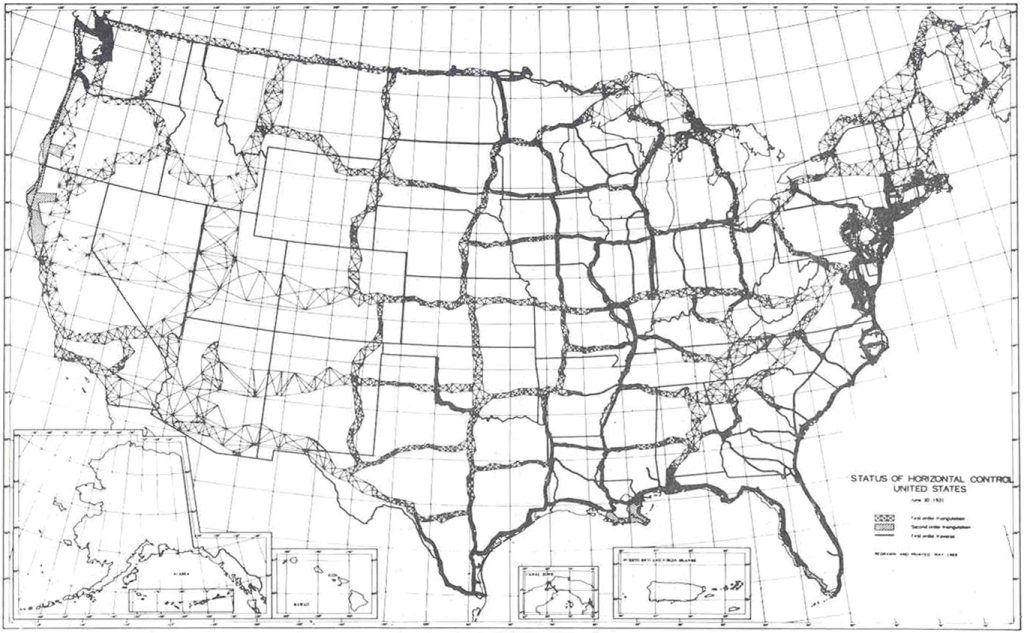

The setting for figure 1 is a wheat field in Osborne, Kansas, which has a historic distinction that is central to its self-definition: it was designated by geographers as the geodetic centre of North America.[1] A national system based on coordinates came into use in the late-nineteenth century to survey the continent. A federal agency created what is called a triangulation station at Osborne, making it a fixed and central point. Networks of triangles are calculated eastward and westward from there to survey longitude, latitude, elevation and shoreline (fig. 2).[2] Osborne marks the point from which surveying and global positioning extend in all directions across North America.

Fig. 02: Triangulated mapping that emanates from Kansas as a means to survey the nation-state.

Dawit Petros’s work asks, ‘What is one’s relationship to place?’[3] He underlines through global conversation the complicated transnational, polycentric trajectories underlying a sense of place. One trajectory is a mapping system that contributed to modernisation in North America. As such, it is an end result of the colonisation process that claimed land from indigenous peoples across the North American continent. The artwork therefore engenders a disconnection regarding the stereotype that the Kansas prairie is occupied by European Americans, both historically and today. For instance, African American pioneers settled Kansas in the late-nineteenth century, and their descendants remain today. Another trajectory regarding the sense of place is Dawit Petros’s invocation of Clement Greenberg’s critical look at Western modernist painting, which dominates the methodological understanding of art in the field of art history. Figure 1 invokes a disconnection from this mainstream Western art history.

Surveying modern European art history

In a formative 1965 article titled Modernist Painting, Greenberg expostulated, ‘Flatness, two-dimensionality, was the only condition painting shared with no other art, and so Modernist painting oriented itself to flatness as it did to nothing else’.[4] The monochromatic square of colour in figure 1 is reminiscent of the history of modern Western art, including Abstract Expressionist American art from the 1940s through 1960s. The influential critic Clement Greenberg labelled the style of art ‘Color Field painting’. Artists such as Helen Frankenthaler, Sam Gilliam, Frank Bowling, Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman painted large fields of single colours. The flat, solid colours, understood as pure and monolithic, became the sole subject matter of the artwork. Greenberg contrasted the Color Field artists’ treatment of space in terms of flat planes with the earlier representation of three-dimensional space by ‘Old Masters’ through one-point perspective and the horizon line.

Dawit Petros refers to Greenberg’s framing of Western art history. The artist manufactured a set of barellas, or handcarts, used among Habesha peoples in the Horn of Africa.[5] He travelled with a three-dimensional barella to Kansas, photographing it against land (fig. 1). The artist aligned the top white wooden handle of an olive-green square against the white horizon line that divides the field from the sky. The alignment can only be observed by a slight interruption in the horizontal green line that splits the top half of the entire photograph into a field of white colour and the bottom portion into a field of green. Dawit Petros identifies the horizon line but stops short of using the one-point perspective perfected by Renaissance artists. Instead, he references the Color Field style.

Fig. 03: A photographic archive by Dawit L. Petros of earth, sky and built form from Ethiopia.

The flat, olive-green square in the centre of the photograph was sourced from images of Ethiopian land using a process of enlarging digitalised photographic details.[6] The photographed colours are in fact digitalised details of the ground and the earth from Ethiopia (fig. 3).[7] Dawit Petros photographed various patches of ground in Ethiopia, and in each one a dominant colour was brought forward. Dawit Petros then abstracted the colours from the photographs using computer software to generate a square of colour. By using photographs sourced from his visit to Ethiopia, Dawit Petros draws Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa into ongoing dialogues about modernity. The artwork effectively invokes a restitutive global reconnection.

In figure 1, the olive-green plane or field of colour is placed on top of what at first glance appears to be another flat plane of colour. But on closer inspection, the bright green, flat colour ‘field’ that forms the background of the bottom half of the artwork is a field, in the literal sense, of Kansas wheat. Therefore, a photographed slice of Ethiopian land is held against a photographed section of land in Kansas. Because of the use of modernism’s two-dimensional flat planes instead of the Renaissance’s illusion of three-dimensional space, it appears as if the geographic distance between the green Kansas field and the olive-green Ethiopian-sourced colour field has now been collapsed and eradicated. In effect, the artist has disconnected the physical separation between two continents.

Reconstituting global processes

The artist stands in the middle of the wheat field behind the green square, and only his two hands can be seen (fig. 1). The bodily presence of the brown hands and the Ethiopian-sourced olive-green square inscribes an African presence into the work’s polycentric modernities in a way that does not objectify the black or brown body. The artist explained in an interview that he decided not to place the body on display, but used the barella to stand in for the body, and that ‘within that refusal is agency’.[8] The African presence in the middle of Kansas iterates a narrative of postcolonial migration and new African diasporas. Dawit Petros lived in Kansas for the duration of an artist residency, and his encounter with Ethiopia for this series reminds us of his emigration. Dawit Petros relocated several times after his birth in Asmara, Eritrea. When he was very young, his family moved to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and had to leave again during the Ethiopian Red Terror in 1977. The family finally moved to Saskatoon, Canada, where the artist would live out the rest of his youth.

The Osborne work alludes not only to new African diasporas but also, through the barella, to colonialism and hidden migrant labour. Dawit Petros encountered a version of the square with handles that serves as a handcart for construction workers when he was in Ethiopia. The handcart was brought to the Horn of Africa through Italian occupation and retained the Italian name in its new home (fig. 4).[9]

Fig. 04: Two women in Ethiopia demonstrating a barella handcart to carry materials.

While barellas signify the Horn of Africa’s colonial history, Dawit Petros exploited the fact that their appearance also evokes works of Western modernism, particularly Piet Mondrian’s squares of pure colour. Dawit Petros was inspired by another Dutch artist named Bas Jan Ader,[10] a contemporary, experimental artist who himself had investigated and interrogated Mondrian in 1960s performance art. Mondrian’s work, created during the first half of the twentieth century, served as a predecessor for the Color Field artists. Dawit Petros disrupts the trajectory of European modernism again by sourcing colour from the Ethiopian land and by referring to Mondrian by way of Ader, himself an immigrant to the United States, in his case from Holland in 1963.

This depiction within the artwork of the act of looking from the perspective of someone with a brown body supplants the presumed white male gaze that dominated Western modernism. The primacy given to Western modernity in the history of art is cancelled by the African specificity Dawit Petros brings through the presence of his brown body and Ethiopian-sourced colour fields. The artwork disconnects the idea of a solely white population from the state of Kansas by reminding us of Native Americans, new African diasporas, migrant farm laborers, and antebellum and post-antebellum people of colour living in Kansas. As a result, Dawit Petros decentres modernity into polycentric arenas that coalesce and co-occur by restituting global disconnections in the field of art history and in a Kansas field of wheat (fig. 5).[11]

[1] Dawit L. Petros, Barella & Landscape #3, Osborne, Kansas, 2012, archival digital print, 30 x 40” (76.2 x 101.6 cm), photo courtesy of the artist.

[2] ‘Horizontal survey control network in the United States’ (June 1931), Wikimedia (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Horizontal_Control_Network_of_the_United_States_June_1931.jpg, 12.05.2023).

[3] Olga Khvan, ‘“Sense of Place” Exhibit at the MFA Marks Homecoming for Dawit L. Petros’, Boston Magazine, 11 November 2013.

[4] Clement Greenberg, ‘Modernist Painting’, in Art and Literature 4 (Spring 1965): 193-201. Reprinted in Art in Theory 1900-1990, ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, 1993), 756.

[5] Dawit L. Petros, interview with Andrea Frohne: Brooklyn, NY, 2014. Habesha refers to people of Ethiopia and Eritrea without specifying the name of a country. Traditionally, it referred to those who live in the highlands, a terrain that straddles the border.

[6] Dawit L. Petros.

[7] Dawit L. Petros, Notations (A Catalogue of Addis Ababa), Artist’s Archive, 2010, courtesy of the artist.

[8] Dawit L. Petros, interview with Andrea Frohne: Brooklyn, NY, 2014.

[9] Dawit L. Petros, photograph taken on a research trip from personal archive, n.d. Courtesy of the artist.

[10] Dawit L. Petros, interview with Andrea Frohne: Brooklyn, NY, 2014.

[11] Dawit L. Petros, Sense of Place series, 2012-2013. Barellas #1-6 in foreground, 2012. Archival digital prints; enamel on MDF, sapele, and pine. Installation view in Encounters Beyond Borders: Contemporary Artists from the Horn of Africa at the Kennedy Museum of Art, Ohio University, 2016, photo courtesy of Ben Siegel.

Bibliography

Greenberg, Clement. ‘Modernist Painting’. In Art and Literature 4 (Spring 1965): 193-201. Reprinted in Art in Theory 1900-1990, edited by Charles Harrison and Paul Wood. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, 1993.

Khvan, Olga. ‘“Sense of Place” Exhibit at the MFA Marks Homecoming for Dawit L. Petros’. Boston Magazine, 11 November 2013.

Petros, Dawit. Interview with Andrea Frohne: Brooklyn, NY, 2014.