In

Blog 2022

christina brauner

Healthy and wealthy without you...

The lure of paradise, the hint of distant yet accessible fortunes, the promise of exotic luxuries available right here and now – these are commonplaces in the long history of commodity advertising.

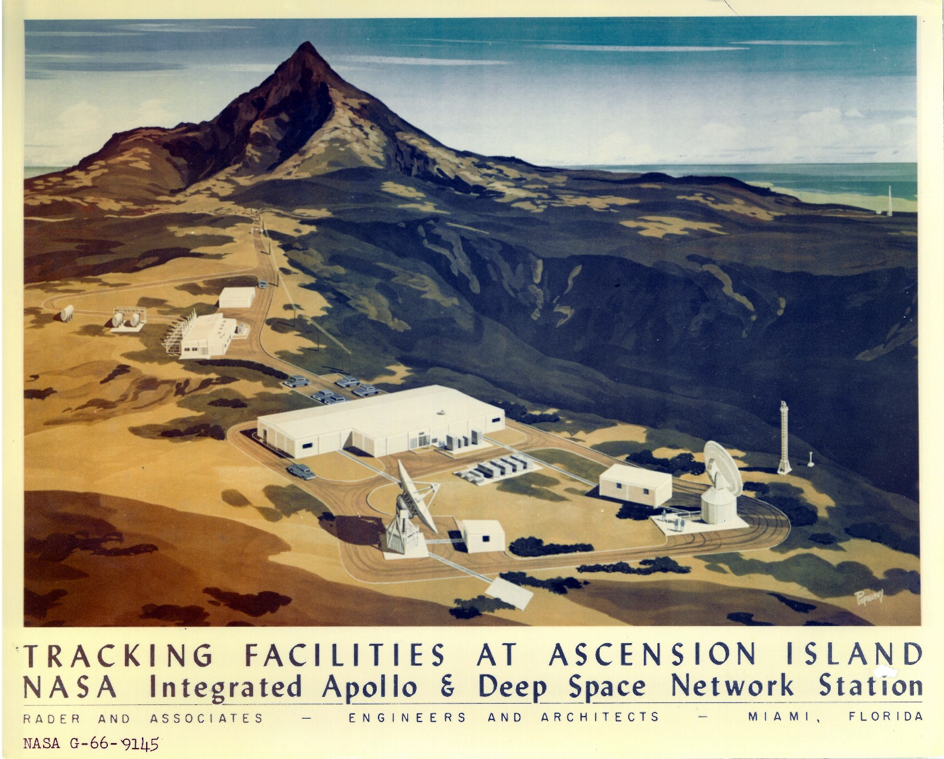

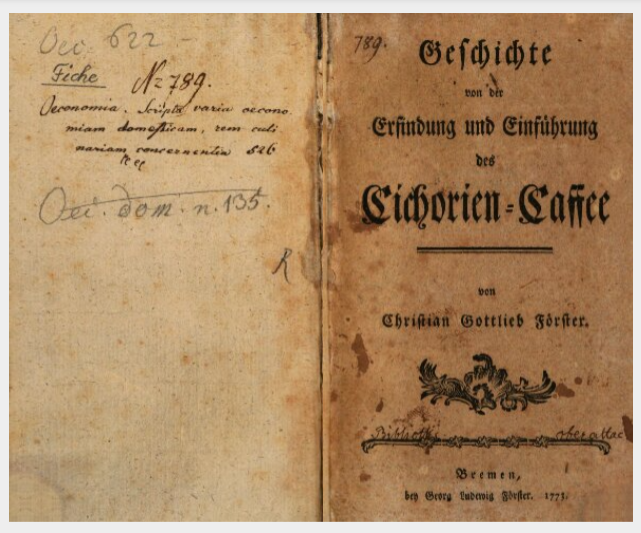

[1] Yet, there is also a long history of rejecting them in favour of promoting local goods. Take the trademark depicted above from the 1770s: through an expressive gesture, the peasant, busy sowing his field, turns away the ship arriving from an exotic shore. The inscription acerbates the gesture, which reads: ‘Healthy and rich without you’. This implies the rejection of colonies and colonial goods in general – coffee in particular – in favour of what is called ‘German coffee’, a drink made from

chicory roots instead of coffee beans.

[2]

As a substitute for ‘real’ or ‘foreign’ coffee, ‘German coffee’ comes with connective and disconnective features simultaneously. It was part of what some contemporaries had already identified as ‘diet revolutions’ – the sometimes slow, sometimes quite quick establishment of ‘new’ foods and consumables such as tea, coffee, chocolate, and – with a somewhat longer history – sugar and spices in European kitchens and on European tables.

[3] Alongside other substitutes, such as herbal tea (in place of imported Asian tea), ‘German coffee’ signals both the growing popularity of ‘global goods’ and the attempt to domesticise them and limit the impact of world trade on the domestic economy. While others merely deplored the demise of good olde German beer and published verbose condemnations of the new luxuries, Christian Gottlieb Förster and fellow champions of the chicory coffee business actively responded to the new consumables, sometimes by even promoting a new product to replace them.

[4]

Drinking chicory coffee in place of imported coffee, the trademark suggests, protects both health and wealth. The act of consumption apparently connects the physical body to the body politick, the wellbeing of the individual to that of the political economy at large. In Förster’s 1773 treatise about the history of chicory coffee, clearly written with an intention to advertise, this connection is established through metaphors, relying on images of circulation and sickness, as well as through statistics. In line with the contemporary fashion of assessing the world through numbers, the treatise features a considerable amount of data on coffee imports and prices. They call upon the individual consumer to relate their own foodways to the economy at large and think about their personal share in the harmful currency drain.

[5] Aligning imports and incorporation, Förster ties together health and wealth, the individual and the collective.

(Image courtesy of the

Bavarian State Library digital collection)

Consequently, numbers come with emotions and a call for action. Förster describes his personal reaction to the results from his accounting work in very corporeal terms: ‘…I felt queasy. I turned to bloodletting, drank a lot of water, took a lemon laying before me, yet, as it was foreign, threw it away again with some force, shattering my punch bowl’.

[6] Yet, he continues, ‘the Fatherland and our body (sic!) still are strong enough to recover; but it is time, high time’.

[7] Förster directs this urgent appeal, above all, to German women as caretakers of house, home and husbands. While blaming Germany’s exposure to outlandish influences mainly on men and male weaknesses, he calls upon female wisdom and virtues to replace foreign fashion and food with authentic and healthy German goods – even by means of withholding their kisses.

[8]

There was a very physical element involved in relating individual consumption to the ‘Fatherland’ and its political economy – namely, the specific nature of German bodies. Such a notion was by no means an eighteenth-century invention; rather, it emerges from a centuries-long tradition of thinking about bodies through their interaction with the environment and climate, with ways of life and, not least, with foodways. This tradition, known as

humoral pathology, was rooted in difference, in different

complexiones that were shaped by and at the same time required different ways and conditions of living. Bodies were different, but they were also malleable, and this was what made food both so powerful and so dangerous.

[9]

What Talal Asad and others have suggested regarding ‘Europe’ as a whole also holds true for ‘Germanness’ in particular: these concepts were shaped through expansion and entanglements.

[10] Studying practices of natural history in early modern German lands, for instance, Alix Cooper has shown how notions of the ‘domestic’ emerged through the encounter with the world at large.

[11] This goes back to the dawn of the so-called ‘European expansion’. Indeed, while humoral pathology was rooted in ancient medical discourse, by the late Middle Ages, it had changed.

Complexio had always been an individual issue, yet, increasingly, a tendency towards collectivisation of

complexiones and essentialisation of skin colour emerged – a development inextricably tied to colonial expansion and slave trade.

[12]

Protecting ‘German bodies’ from foreign influence, thus, was linked to the racialisation of bodies elsewhere. Moreover, through the nexus of the German body, both individual and politick, Förster also envisages Germany as an entity of political economy at a time where no such thing existed, at least in terms of political institutions. To put it bluntly: Germany was threatened by global connections

prenatally. At the same time, the market was the place where the ‘Fatherland’ could be rescued, through patriotic acts of purchase and consumption. Whether chicory coffee indeed helped to decrease the consumption of ‘real’ coffee is still open to debate. Some scholars have even suggested that the cheaper substitute inadvertently prepared the ground for the latter establishment of ‘real’ coffee throughout German society, as it allowed non-elite consumers to acquire respective drinking practices.

[13]

Throughout the world of the twenty-first century, the trope of protecting the nation, its borders and its economy has come back with a vengeance – if indeed it ever left. Studying the global history of nationalism, thus, seems to be a timely endeavour for historians interested in dis:connectivity. Doing so means exploring dis:connections in terms of dialectics rather than dichotomies, studying the interplay of connections and disconnections both in terms of unintended effects and deliberate politics.

[14]

[1] Cf., e.g., Paul Freedman, ‘Spices and Late-Medieval European Ideas of Scarcity and Value’,

Speculum 80, no. 4 (2005): 1209–27; Catherine Molineux, ‘Pleasures of the Smoke: “Black Virginians” in Georgian London’s Tobacco Shops’,

William and Mary Quarterly 64, no. 2 (2007): 327–76.

[2] For an explanation of the trademark, see Christian G. Förster,

Geschichte von der Erfindung und Einführung des Cichorien-Caffee (Bremen, 1773), 51; the 1864 edition of Grimm’s dictionary mentions ‘German coffee’ as a synonym for ‘chicory coffee’: ‘cichorienkaffee ein surrogat (auch deutscher kaffee genannt)’, see Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm,

Deutsches Wörterbuch. Fünfter Band. K (Leipzig, 1873), 21f.

[3] Johann G. Leidenfrost, ‘Revolutionen in der Diät von Europa seit 300 Jaren’, in

August Ludwig Schlözer’s Briefwechsel, meist historischen und politischen Inhalts, vol. 8, iss. 44 (Göttingen, 1781), 93–120; for an overview, see Anne E. C. McCants, ‘Global History and the History of Consumption: Congruence and Divergence’, in

Global History and New Polycentric Approaches. Europe, Asia and the Americas in a World Network System, ed. Lucio de Sousa and Manuel P. Garcia (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 241–53; and the respective contributions in Frank Trentmann, ed.,

The Oxford Handbook of the History of Consumption (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012); while this debate long focused on Western Europe and its colonial empires, Central European entanglements with global trade and consumption have only recently become the subject of extensive systematic study, cf., e.g., Jutta Wimmler and Klaus Weber, eds.,

Globalized Peripheries. Central Europe and the Atlantic World, 1680-1860 (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2020).

[4] See Förster,

Geschichte von der Erfindung und Einführung des Cichorien-Caffee; for the trademark and the respective enterprise, see Peter Albrecht, ‘Die Erschließung neuer Absatzwege durch Braunschweiger Firmen in der zweiten Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts’, in

Innovationsgeschichte. Erträge der 21. Arbeitstagung der Gesellschaft für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte, 30. März bis 2. April 2005 in Regensburg, ed. Rolf Walter (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2007), ill. 181; despite Förster’s claims to the contrary, there were earlier propagators of chicory coffee, see Christian Hochmuth,

Globale Güter - lokale Aneignung. Kaffee, Tee, Schokolade und Tabak im frühneuzeitlichen Dresden (Konstanz: UVK Verlag, 2008), 71f.; on substitutes and ‘domestication’, see Julia A. Schmidt-Funke, ‘“Eigene fremde Dinge”. Surrogate und Imitate im langen 18. Jahrhundert’, in

Präsenz und Evidenz fremder Dinge im Europa des 18. Jahrhunderts, ed. Birgit Neumann (Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2018), 529–49; and Anne Gerritsen, ‘Domesticating Goods from Overseas: Global Material Culture in the Early Modern Netherlands’,

Journal of Design History 29, no. 3 (2016): 228–44.

[5] For an insightful take on the emotional and moralising usages of statistics, see David Kuchenbuch, ‘“Fernmoral”. Zur Genealogie des glokalen Wissens’,

Merkur 70, no. 807 (2016): 40–51.

[6] Förster,

Geschichte von der Erfindung und Einführung des Cichorien-Caffee, 12: ‘…mir ward schlimm. Ich ließ mir die Ader öfnen, trank viel Wasser, ergrif eine vor mir liegende Citrone, doch, da sie ausländisch war, warf ich sie mit Ungestüm weg, und zerschmettere damit meine Punsch-Schale.’

[7] Ibid. 14: ‘…das Vaterland und unser Körper haben noch Kräfte, um sich erholen zu können; es ist aber Zeit, und zwar die höchste.’

[8] Ibid. 15: ‘…geben sie ihm keinen Kuß, wenn er ihnen nicht monathlich einen Entwurf, oder auch nur einen gesunden Gedanken zur Verbesserung des Vaterlandes opfert’. The history of eighteenth-century consumer boycotts has recently drawn some attention but mainly in the context of the abolitionist movement. The case of Förster’s chicory coffee demonstrates, once more, the different political usages such early practices of ‘global responsibilisation’ could be put to.

[9] For an introduction, see Steven Shapin, ‘“You Are What You Eat”: Historical Changes in Ideas about Food and Identity’,

Historical Research 87, no. 237 (2014): 377–92; and David Gentilcore,

Food and Health in Early Modern Europe. Diet, Medicine and Society, 1450-1800 (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016).

[10] Talal Asad, ‘Muslims and European Identity: Can Europe Represent Islam?’, in

The Idea of Europe. From Antiquity to the European Union, ed. Anthony Pagden (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 220.

[11] Alix Cooper,

Inventing the Indigenous. Local Knowledge and Natural History in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007); see also Peter Hess, ‘Protest from the Margins: Emerging Global Networks in the Early Sixteenth Century and Their German Detractors’, in

Other Globes. Past and Peripheral Imaginations of Globalization, ed. Simon Ferdinand, Irene Villaescusa-Illán, and Esther Peeren (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 41–62; and Bethany Wiggin, ‘Globalization and the Work of Fashion in Early Modern German Letters’,

Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 11, no. 2 (2011): 35–60.

[12] See Gentilcore,

Food and Health in Early Modern Europe. Diet, Medicine and Society, 1450-1800, chapter 4; Rebecca Earle,

The Body of the Conquistador. Food, Race and the Colonial Experience in Spanish America, 1492–1700 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), esp. chapter 2; Valentin Groebner, ‘Haben Hautfarben eine Geschichte? Personenbeschreibungen und ihre Kategorien zwischen dem 13. und 16. Jahrhundert’,

Zeitschrift für Historische Forschung 30, no. 1 (2003): 1–17, esp. 12-17; for the ongoing debate on racism in the Middle Ages, see Vanita Seth, ‘The Origins of Racism: A Critique of the History of Ideas’,

History and Theory 59, no. 3 (2020): 343–68.

[13] See Hans J. Teuteberg, ‘Kaffeetrinken sozialgeschichtlich betrachtet’,

Scripta Mercaturae 14, no. 1 (1980): 41f.; Hochmuth,

Globale Güter - lokale Aneignung. Kaffee, Tee, Schokolade und Tabak im frühneuzeitlichen Dresden, 71f. Hochmuth links the decreasing volume of coffee imports in Dresden after the 1760s to the rising consumption of coffee substitutes (88f.).

[14] Cf. Cemil Aydin et al., ‘Rethinking Nationalism’,

American Historical Review 127, no. 1 (2022): 311–71; Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing,

Friction. An Ethnography of Global Connection (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005).

bibliography

Albrecht, Peter. ‘Die Erschließung neuer Absatzwege durch Braunschweiger Firmen in der zweiten Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts’. In

Innovationsgeschichte. Erträge der 21. Arbeitstagung der Gesellschaft für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte, 30. März bis 2. April 2005 in Regensburg, edited by Rolf Walter, 175–89. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2007.

Asad, Talal. ‘Muslims and European Identity: Can Europe Represent Islam?’ In

The Idea of Europe. From Antiquity to the European Union, edited by Anthony Pagden, 209–27. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Aydin, Cemil, Grace Ballor, Sebastian Conrad, Frederick Copper, Nicole CuUnjieng Aboitiz, Richard Drayton, Michael Goebel, et al. ‘Rethinking Nationalism’.

American Historical Review 127, no. 1 (2022): 311–71.

Cooper, Alix.

Inventing the Indigenous. Local Knowledge and Natural History in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Earle, Rebecca.

The Body of the Conquistador. Food, Race and the Colonial Experience in Spanish America, 1492–1700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Förster, Christian G.

Geschichte von der Erfindung und Einführung des Cichorien-Caffee. Bremen, 1773.

Freedman, Paul. ‘Spices and Late-Medieval European Ideas of Scarcity and Value’.

Speculum 80, no. 4 (2005): 1209–27.

Gentilcore, David.

Food and Health in Early Modern Europe. Diet, Medicine and Society, 1450-1800. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016.

Gerritsen, Anne. ‘Domesticating Goods from Overseas: Global Material Culture in the Early Modern Netherlands’.

Journal of Design History 29, no. 3 (2016): 228–44.

Grimm, Jacob, and Wilhelm Grimm.

Deutsches Wörterbuch. Fünfter Band. K. Leipzig, 1873.

Groebner, Valentin. ‘Haben Hautfarben eine Geschichte? Personenbeschreibungen und ihre Kategorien zwischen dem 13. und 16. Jahrhundert’.

Zeitschrift für Historische Forschung 30, no. 1 (2003): 1–17.

Hess, Peter. ‘Protest from the Margins: Emerging Global Networks in the Early Sixteenth Century and Their German Detractors’. In

Other Globes. Past and Peripheral Imaginations of Globalization, edited by Simon Ferdinand, Irene Villaescusa-Illán, and Esther Peeren, 41–62. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

Hochmuth, Christian.

Globale Güter - lokale Aneignung. Kaffee, Tee, Schokolade und Tabak im frühneuzeitlichen Dresden. Konstanz: UVK Verlag, 2008.

Kuchenbuch, David. ‘“Fernmoral”. Zur Genealogie des glokalen Wissens’.

Merkur 70, no. 807 (2016): 40–51.

Leidenfrost, Johann G. ‘Revolutionen in der Diät von Europa seit 300 Jaren’. In

August Ludwig Schlözer’s Briefwechsel, meist historischen und politischen Inhalts, 8, iss. 44:93–120. Göttingen, 1781.

McCants, Anne E. C. ‘Global History and the History of Consumption: Congruence and Divergence’. In

Global History and New Polycentric Approaches. Europe, Asia and the Americas in a World Network System, edited by Lucio de Sousa and Manuel P. Garcia, 241–53. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Molineux, Catherine. ‘Pleasures of the Smoke: “Black Virginians” in Georgian London’s Tobacco Shops’.

William and Mary Quarterly 64, no. 2 (2007): 327–76.

Schmidt-Funke, Julia A. ‘“Eigene fremde Dinge”. Surrogate und Imitate im langen 18. Jahrhundert’. In

Präsenz und Evidenz fremder Dinge im Europa des 18. Jahrhunderts, edited by Birgit Neumann, 529–49. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2018.

Seth, Vanita. ‘The Origins of Racism: A Critique of the History of Ideas’.

History and Theory 59, no. 3 (2020): 343–68.

Shapin, Steven. ‘“You Are What You Eat”: Historical Changes in Ideas about Food and Identity’.

Historical Research 87, no. 237 (2014): 377–92.

Teuteberg, Hans J. ‘Kaffeetrinken sozialgeschichtlich betrachtet’.

Scripta Mercaturae 14, no. 1 (1980): 27–54.

Trentmann, Frank, ed.

The Oxford Handbook of the History of Consumption. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt.

Friction. An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Wiggin, Bethany. ‘Globalization and the Work of Fashion in Early Modern German Letters’.

Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 11, no. 2 (2011): 35–60.

Wimmler, Jutta, and Klaus Weber, eds.

Globalized Peripheries. Central Europe and the Atlantic World, 1680-1860. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2020.

citation information

Continue Reading

(Image courtesy of the

(Image courtesy of the

Together with the Munich Centre for Global History, global dis:connect recently had the privilege of hosting a stimulating workshop titled Re-examining Empires from the Margins: Towards a New Imperial History of Europe, organised by the inimitable

Together with the Munich Centre for Global History, global dis:connect recently had the privilege of hosting a stimulating workshop titled Re-examining Empires from the Margins: Towards a New Imperial History of Europe, organised by the inimitable