Images of dis:connectivity: Leon Trotsky on Büyükada

burcu dogramaci

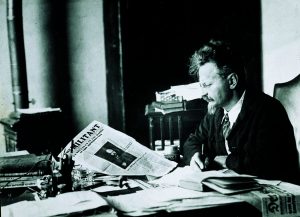

Trotsky at his desk, Büyükada/Prinkipo, 1931, in: Robert Service. Trotzki. Eine Biographie. Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2012, ill. 18.

[1] In his exile on Büyükada/Prinkipo, one of the largest of the Princes’ Islands off the Asian side of Istanbul, Russian politician Leon Trotsky was equally connected and disconnected to the world. This photograph shows him at his desk. He is reading the newspaper The Militant and taking notes. An open book lies in front of him, with other daily newspapers underneath. The photograph is taken at close range and portrays the exile as an intellectual worker who keeps himself informed − not as an outcast cut off from political events.

Trotsky’s island exile lasted a total of four years. Banished by Stalin, Trotsky and his entourage were sent to Istanbul by ship in 1929. Trotsky relocated several times in the city on the Bosporus before he settled down on Büyükada/Prinkipo, which seemed to offer Trotsky protection. From Istanbul, the island could be reached only by boat, so arrivals were easy to observe. The banished politician lived in constant danger of attempts on his life because he feared attacks by Stalin’s agents.

Being off, being on

Although Trotsky’s freedom to act, in his insular seclusion, was limited, and he hardly left the island, he participated in world events. On Büyükada/Prinkipo, Trotsky subscribed to international daily papers and political pamphlets, which arrived with a two- or three-day delay.[2] The author Georges Simenon, who visited Trotsky on the island in 1933 for an interview, writes:

“On the desk there is a chaos of newspapers from all over the world. Paris-Soir lies at the very top of one pile. Doubtless Trotsky has skimmed through the paper before I arrived. […] The rest of the time he stays in his study, which is so far from the world outside and yet at the same time so close to it. ‘Unfortunately I get the papers with several days’ delay’.” [3]

Moreover, photos of his desk, which also evidence his self-presentation as a yet-influential politician, show international newspapers such as The New York Times or the American Trotskyist paper The Militant. Also, Trotsky regularly read the French daily Le Temps, the staunchly conservative Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, received Turkish daily papers, whose headlines he was able to decipher even without knowing the language, and he had locally printed international purchased for him in the shops on the jetty.[4] Trotsky thus consumed a geographically and politically broad spectrum of media. This is probably what enabled him to preserve a relatively nuanced view of the world even from his island exile.

Trotsky was highly productive there, wrote newspaper and magazine articles and authored several books. During his time on the Princes’ Island Trotsky published a history of the Russian Revolution and his autobiography. .[5] Furthermore, he wrote about fascism in Europe and National Socialism in Germany, and he published articles on the political situation in Austria, on the Spanish Revolution and on Stalinism in the Soviet Union.[6] The library he had brought with him, archival material brought from the Soviet Union and his own memories formed the basis for his publications.[7] Moreover, Trotsky was regularly visited by supporters and exchanged letters with like-minded political friends and Trotskyist followers, family members and intellectuals.[8]

Island exile

Reflecting on Trotsky’s life and work on Büyükada/Prinkipo, some initial thoughts arise about exile as an insular space of experience. Islands can signify both isolation and protection as well as banishment and refuge. In Byzantine times, Büyükada/Prinkipo was a place of banishment that offered undesired princes and princesses coerced shelter.[9] For Büyükada/Prinkipo, which is an archipelago, one can adapt Ottmar Ette’s distinction between Insel-Welt (‘island world’) and Inselwelt (‘archipelago world’). An island world is ‘an island that is self-contained, has clear-cut boundaries and is dominated by a clear internal order […], forming in itself and for itself a unit that is delimited from the outside’.[10] On the other hand, an Inselwelt is associated with .[11] From the largest Princes’ Island, one can see not only the surrounding islands, inhabited and uninhabited alike, but also the mainland − the proximate Asian and distant European parts of Istanbul.

Dis:connectivity and archipelagic thinking

Büyükada/Prinkipo is part of an island community, connected to both Europe and Asia, to both halves of Istanbul and their respective histories. Between them is the sea, which is always an intermediary and a boundary or barrier.[12]

Independence, isolation, but also participation and a kaleidoscopic view of the world − or at least of two continents − result from island exile.

Despite the distance of the island, Trotsky managed to participate in world events through publications, reading daily newspapers and visits by political supporters. He was able to productively counteract the (enforced) seclusion of island life and from his exile to develop a keen and sympathetic eye for world history. Consequently, Trotsky’s work in exile is not far removed from the kind of archipelagic thinking Édouard Glissant describes .[13] Archipelagic thinking is to not only see the island, but to be aware of the connection of the particular to the larger whole.[14] While in Exile on Büyükada/Prinkipo, the Russian exile became highly productive. The island life of Trotsky was an exile within exile.

[1] The ideas in this post derive from Burcu Dogramaci Burcu Dogramaci, ‘Arrival City Istanbul: Flight, Modernity and Metropolis at the Bosporus. With an Excursus on the Island Exile of Leon Trotsky’, in Arrival Cities. Migrating Artists and New Metropolitan Topographies in the 20th Century, hg. von Burcu Dogramaci (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2020), 205–25.

[2] Jean van Heijenoort, With Trotsky in Exile. From Prinkipo to Coyoacán. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1978), 20.

[3] George Simenon, ‘Besuch bei Trotzki (Paris-Soir, 16./17. Juni 1933)“, in Das Simenon-Lesebuch. Erzählungen, Reportagen, Erinnerungen. Briefwechsel mit André Gide. Brief an meine Mutte, hg. von George Simenon (Zürich: Diogenes Verlag, 2002), 223.

[4] Heijenoort, With Trotsky in Exile. From Prinkipo to Coyoacán., 20.

[5] Robert Service, Trotzki. Eine Biographie. (Berlin: Suhrkamp Verlag, 2012), 500.

[6] Isaac Deutscher, Trotzki. Der verstoßene Prophet 1929–1940 (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1972), 97–152.

[7] Service, Trotzki. Eine Biographie., 500.

[8] Catherine Pinguet, Les îles des Princes. Un archipel au large d’Istanbul. (Tharaux: Empreinte, 2013), 117.

[9] Pinguet, 29–33.

[10] Ottmar Ette, ‘Insulare ZwischenWelten der Literatur. Inseln, Archipele und Areale aus transarealer Perspektive.’, in Inseln und Archipele. Kulturelle Figuren des Insularen zwischen Isolation und Entgrenzung, hg. von Anna Wilkens (Bielefeld: Transcipt Verlag, 2011), 26.

[11] Ette, 26.

[12] Anna Wilkens, ‘Ausstellung zeitgenössischer Kunst: Inseln – Archipele – Atolle. Figuren des Insularen.’, in Inseln und Archipele. Kulturelle Figuren des Insularen zwischen Isolation und Entgrenzung, ed. Anna Wilkens (Bielefeld: Transcipt Verlag, 2011), 64.

[13] Édouard Glissant, Kultur und Identität. Ansätze zu einer Poetik der Vielheit (Heidelberg: Wunderhorn, 2005), 34.

[14] See: Marsha Pearce, ‘Die Welt Als Archipel /The World as Archipelago.’, Kulturaustausch/Cultural Exchange: Journal for International Perspectives, Nr. 2 (2014): 18 f.

bibliography

Deutscher, Isaac. Trotzki. Der verstoßene Prophet 1929–1940. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1972.

Dogramaci, Burcu. „Arrival City Istanbul: Flight, Modernity and Metropolis at the Bosporus. With an Excursus on the Island Exile of Leon Trotsky“. In Arrival Cities. Migrating Artists and New Metropolitan Topographies in the 20th Century, herausgegeben von Burcu Dogramaci, 205–25. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2020.

Ette, Ottmar. „Insulare ZwischenWelten der Literatur. Inseln, Archipele und Areale aus transarealer Perspektive.“ In Inseln und Archipele. Kulturelle Figuren des Insularen zwischen Isolation und Entgrenzung, herausgegeben von Anna Wilkens, 13–56. Bielefeld: Transcipt Verlag, 2011.

Glissant, Édouard. Kultur und Identität. Ansätze zu einer Poetik der Vielheit. Heidelberg: Wunderhorn, 2005.

Heijenoort, Jean van. With Trotsky in Exile. From Prinkipo to Coyoacán. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1978.

Pearce, Marsha. „Die Welt Als Archipel /The World as Archipelago.“ Kulturaustausch/Cultural Exchange: Journal for International Perspectives, Nr. 2 (2014): 18–19.

Pinguet, Catherine. Les îles des Princes. Un archipel au large d’Istanbul. Tharaux: Empreinte, 2013.

Service, Robert. Trotzki. Eine Biographie. Berlin: Suhrkamp Verlag, 2012.

Simenon, George. „Besuch bei Trotzki (Paris-Soir, 16./17. Juni 1933)“. In Das Simenon-Lesebuch. Erzählungen, Reportagen, Erinnerungen. Briefwechsel mit André Gide. Brief an meine Mutte, herausgegeben von George Simenon, 215–31. Zürich: Diogenes Verlag, 2002.

Wilkens, Anna. „Ausstellung zeitgenössischer Kunst: Inseln – Archipele – Atolle. Figuren des Insularen.“ In Inseln und Archipele. Kulturelle Figuren des Insularen zwischen Isolation und Entgrenzung, herausgegeben von Anna Wilkens, 57–98. Bielefeld: Transcipt Verlag, 2011.