Imperial margins take centre stage: a conference report

mikko toivanen & ben kamis

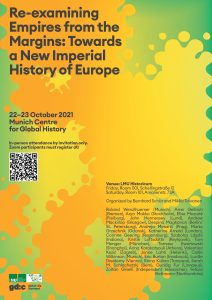

Together with the Munich Centre for Global History, global dis:connect recently had the privilege of hosting a stimulating workshop titled Re-examining Empires from the Margins: Towards a New Imperial History of Europe, organised by the inimitable Bernhard Schär and Mikko Toivanen.

The event was held on 22-23 October 2021, and — thanks to the pandemic — some of the internationally renowned participants were attending remotely. The purpose was to explore the history of imperial entanglements involving those beyond the typical cast of European imperial powers. In other words, what did Nordic imperialism look like? What were the imperial strategies and practices of Central and Eastern Europe?

Bernhard and Mikko opened the conference themselves, remarking how research into imperial histories of ‘marginal’ European powers has been gaining momentum and how this tack can expand and improve our understandings of atypical European colonial history. However, they also noted that much existing research on the subject has focused on individual case studies to the neglect of the underlying global networks and structures. They also added the important caveat that, despite its relative neglect, this research must be wary of recentring Europe in histories of global imperialism and colonisation.

The conference’s first panel dove right in, tackling political and diplomatic engagements with empire from three different perspectives. First, Arne Gellrich discussed the participation of Sweden and Norway in the League of Nations in the interwar years. Gellrich argued that these neutral countries were able to influence colonial policy and promote their governments’ social democratic ideals thanks to the League’s structure, but they ultimately could not overcome the discrimination of colonialism.

Focusing on the same two countries in his talk, Aryo Makko described their efforts to profit from colonial trade through proactive diplomacy around the turn of the twentieth century. These efforts largely rested on a transnational network of citizens of third-party states.

Third, Elise Mazurié examined the international feminist congress held in Algeria in 1932, and how the Swiss delegation pursued a policy of ‘maternalist imperialism’. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the event stopped short of meaningfully criticising French imperialism.

The second panel opted to investigate the creativity involved in transimperial occupations. Andrew Mackillop described how mercenaries, as a professional group, enabled Switzerland to participate in the activities of the largest European imperial powers, following their navies from its landlocked European redoubt out into the oceans of Asia. Despina Magkanari’s work touched a little closer to home, as she examined how Julius Klaproth, an 18th-century German orientalist, navigated academia in imperial Russia with the help of professional networks of scholars. Andreja Mesarič brought us back to the familiar historical turf of missionaries, describing how Slovenian Catholic proselytisers in 19th-century Sudan influenced ideas in Slovenia and the broader Austro-Hungarian Empire about race and colonisation. She also analysed these figures’ recent revival in modern Slovenian discourse.

John Hennessy concluded the panel with a more general, conceptual contribution. He argued for the analytical utility of occupational groups rather than nationalities as an organisational principle.

The workshop went meta in the third session, which featured a transnational group of scholars discussing transimperial academic networks in history. Katherine Arnold opened the session by relating how German naturalists in British Southern Africa were unavoidably implicated in the physical and environmental violence of colonisation.

Naturally, representations always say as much about the representers as they do about the represented, as the next three papers in the panel showed. Corinne Geering illustrated precisely this intuition with museum collections in Vienna, Moscow, Warsaw and Prague and how they informed perceptions of European cultures by displaying artefacts from outside Europe. Similarly, Szabolcs Laszló examined the special case of Hungary and how Hungarian orientalists presented Hungarians’ ostensibly Asian roots in a way that diverged from the broader orientalist movement. Continuing the primordialist theme, Kristín Loftsdóttir reflected on busts made in Iceland by a 19th-century French expedition and how they were used as indicators of Iceland’s rank in the contemporary racial hierarchy.

The fourth panel also revisited familiar territory for global historians: travellers. But the participants did so in novel ways. Evaluating over 100 travel authors, Tomasz Ewertowski devised four categories of empathic solidarity displayed by Polish and Serbian travellers in colonial contexts. By contrast, Anna Karakatsouli focused on a single Greek explorer — Panayiotis Potagos — who found an idiosyncratic niche in the writings of ancient Greek geographers and historians, preferring their representations to the imperial politics of his own time.

Of course, some colonial actors are not only disinterested in imperial politics, but unapologetic. Valentina Kezić described the case of Carl Lehrman, a Croatian explorer who served both under Henry Morton Stanley as well as the Belgian administration in the Congo. According to Kezić, Lehrman remained staunchly and simultaneously loyal to his Croatian home and the Belgian colonial system that he served. And Janne Lahti showed how historical actors could practice imperialism in their own backyards. Specifically, Finnish travellers to the Petsamo region on the Arctic Sea in the 20th century would often reproduce discursive tropes from other colonial contexts, especially with regard to the indigenous Sámis.

The fifth panel examined intra-European cases. The first contribution by Lucile Dreidemy and Eric Burton focused on the Paneuropean Union, an initiative launched by Austria in the 1920s. Contrary to the popular view that this union was an instance of proto-European integration, Dreidemy and Burton discuss its aims of imperial management in Africa and possibly even to become the new face of the Habsburg Empire. Returning to the Finnish context, Rinna Kullaa demonstrated that forced labour migration under Russian rule in the 19th century was sadly a two-way street: Central Asian labourers were used to build tram tracks in Helsinki, while Finns were sent to colonise Siberia. Sarah Schlachetzki closed the panel with a paper on Prussian architecture in Poland in the 18th and 19th centuries, arguing that standardised settlement farms display colonial aims and serve imperial purposes just as representational architecture is known to do.

The workshop’s final session featured three invited discussants, who each commended the quality of the research presented while also reminding the participants not to ignore those at the margins of their margins. Gunlög Fur recalled that margins are always drawn by someone, and women and non-European actors are often left on the outside. Zoltán Ginelli greeted the attention to Central and Eastern Europe, but he warned the authors not to neglect those beyond Europe, nor those who were marginalised within Europe under post-war communist rule. Closing the workshop, Felicia Gottmann cast her gaze upon the papers’ temporal margins, suggesting that comparison with early modern empires can inform and enrich analyses of their modern successors.

Re-examining empires from the Margins was an important event for global dis:connect. It showed that we can hold stimulating, fruitful discussions with international participants even under difficult pandemic conditions. It was also one of the first events we had the privilege to host. As such, it evidenced the confidence the workshop’s illustrious participants have in a yet-young institution. We can only hope that they have profited from the experience as much as we have.

citation information

Toivanen, Mikko, and Ben Kamis. ‘Imperial Margins Take Centre Stage: A Conference Report’. Institute Website. Blog, Global Dis:Connect (blog), 5 October 2022. https://www.globaldisconnect.org/05/10/imperial-margins-take-centre-stage-a-conference-report-by-mikko-toivanen-ben-kamis/?lang=en.

This post has also appeared in issue 1.1 of our in-house journal, static.