In

Blog 2022

roland wenzlhuemer

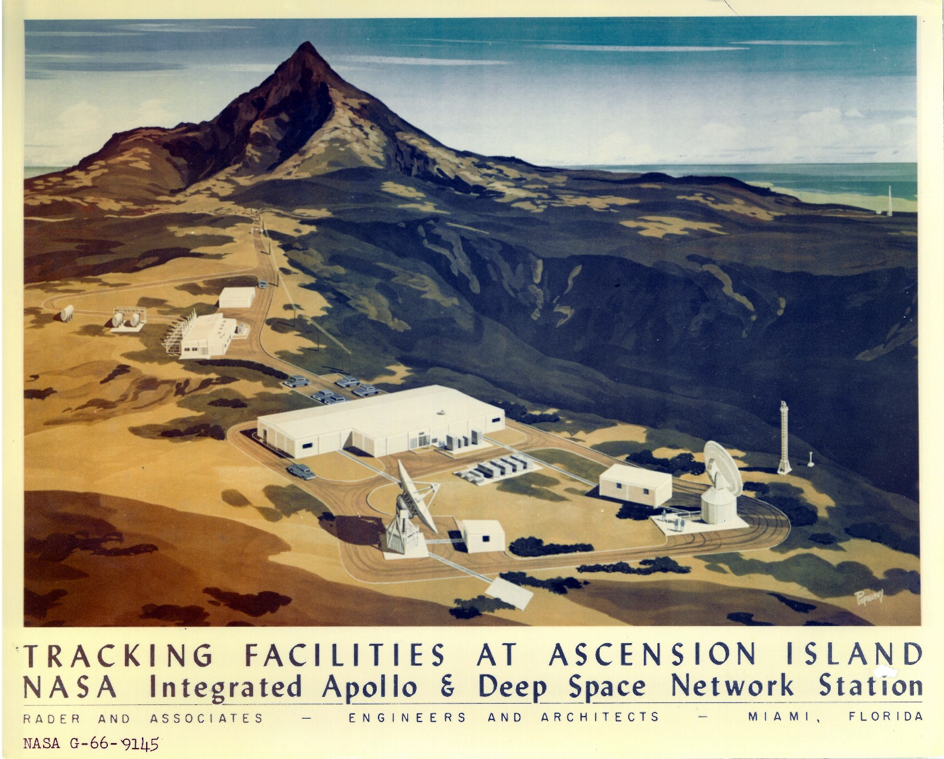

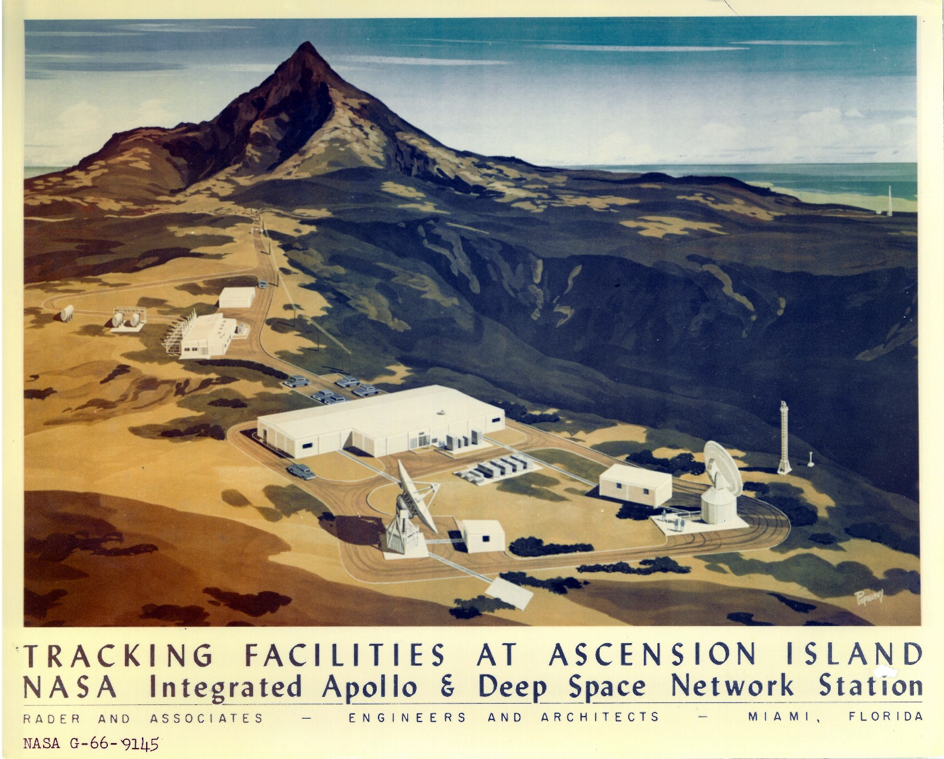

NASA image G-66-9145

The visual archive of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center contains countless fascinating images, among them photographs of the first men on the moon and dozens of variations of the ‘blue marble,’ which never cease to amaze. Even among this fascinating collection, image G-66-9145 stands out.

The painting depicts NASA’s

Manned Space Flight Network Station[1]on Ascension Island, which — thanks to its important role in the Apollo missions — is referred to as

Integrated Apollo & Deep Space Network Station on the painting itself. The credits inform us that the 1966 painting was commissioned by Miami architects

Rader and Associates, who designed several missile-tracking stations for the US government at that time. The painting shows a number of cuboid, single-story buildings connected via roads to two huge antennae and supply facilities. All buildings and facilities are painted white. By itself, it is not a particularly bright white. Set against a mostly ochre, dark background, however, the network station almost seems to shine. Indeed, the entire landscape that surrounds the station is almost surreally barren and desolate. Even the mountain that rises in the background is hardly inviting. Behind the barren scenery, a small glimpse of the sea betrays that the setting is coastal or, indeed, insular.

It is safe to assume that the intention behind the painting was strictly functional. It probably served to inform the contracting authorities about how

Rader and Associates envisioned the station and where exactly it was to be set. Still, the image tells an eloquent story about the remoteness of Ascension Island, its tracking station and the dis:connectivity in which it was immersed.

Ascension Island

Comparing the painting to contemporary photographs of the station and its surroundings, which, by the way, carry the telling name of ‘Devil’s Ashpit’, it emerges that this depiction of barrenness comes surprisingly close to reality. Ascension is a small, remote, volcanic island in the South Atlantic. When the Portuguese first landed in 1501, they found an unwelcoming place. They never settled.

Two hundred years later, the Dutch had little more interest in the island. Once, in 1725, they used it to maroon the seaman Leendert Hasenbosch as a punishment for alleged sexual misconduct. They left Hasenbosch to starve to death.

[2]

Only in 1815 did the British Navy establish a small station on Ascension. Napoleon had been exiled to neighbouring (though still 1.300 km distant) St Helena, and the British wanted to keep an eye on him.

Over the following decades, Ascension developed into a shipping waystation, but constantly suffered from the lack of local supplies and freshwater. Practically all supplies had to be brought in from elsewhere — a complicated and expensive endeavour.

This is what Charles Darwin found and documented when he visited the island on his return journey on HMS Beagle in 1836. Seven years later, Joseph Dalton Hooker, on his way home from a four-year expedition to the Antarctic, also called at Ascension. The botanist, who would later become the director of the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew, was asked by British officers whether he saw any way to improve Ascension’s environment in terms of its habitability. Hooker thought about the matter and came up with the idea of importing trees and other plant species to generate a natural freshwater supply and better soil conditions on the island.

After his departure for England, the Navy started to implement Hooker’s plans, importing seeds and seedlings in massive quantities from all over the world —Argentina, South Africa and Kew Gardens.

[3] Hooker’s plan worked better and faster than expected. Within two decades, Ascension developed a diverse ecosystem and a more favourable microclimate. What had been a barren rock began to flourish. The island’s highest peak was soon referred to as Green Mountain.

Remoteness and connectivity

In the second half of the nineteenth century and Hooker’s wake, Ascension Island became the scene of an experiment in terraforming

avant la lettre. This enterprise could only work thanks to the isolation of the island.

The experiment was generally successful, but it did not convert the entire island into Eden. The peak in the background of our painting is a less-lush part of Green Mountain, and the region of Devil’s Ashpit itself remained uninviting, which was one of the reasons why NASA selected it as the setting for the tracking station. There was no other activity in the area. Or, as it says in the official booklet on the station that NASA had prepared in 1967, ‘This ensures maximum protection from noise or interference’

[4] from other communications facilities on the island. So, the Devil’s Ashpit tracking station was located in a remote corner of an already extremely remote island.

In the 1960s and early 1970s, between 50 and 100 NASA personnel were working there. ‘

There were 16-hour workdays, no TV, and Ascension was the only site where employees couldn’t bring their families. It was that remote’.

And yet, precisely because of its remoteness, Ascension occupied a central role first in terrestrial, then in extra-terrestrial, communication. Already in 1899, the island became the site of a relay station in the emerging global telegraph network, as its location conveniently completed the telegraphic connection between Europe, South America and southern Africa.

During the Second World War, the American Air Force had an airfield built on Ascension to refuel its bombers. And in the 1960s, the tracking station at Devil’s Ashpit played a central role in NASA’s Apollo missions. It was part of a network of 17 tracking stations distributed around the entire globe to secure constant communication with Apollo spacecraft.

[5]

Rumours have it that the staff at the Ascension Island station were the first people on Earth to hear that “the Eagle ha[d] landed”. During the crucial phase of Apollo 11, however, the station was in Earth’s radio shadow and could neither have seen nor heard Neil Armstrong make his ‘small step’ — not even on regular television, as most of the world did on 20 July 1969. There was

no terrestrial television signal on Ascension.

Global dis:connectivity

In 2010, the BBC unearthed the remarkable story of Ascension’s ecosystem. BBC science reporter Howard Falcon-Lang was clearly impressed by the terraforming experiment. ‘By a bizarre twist, this great imperial experiment may hold the key to the future colonization of Mars’,

he wrote and quoted a contemporary ecologist who is convinced that much can be learned from Ascension for the future establishment of human colonies beyond earth. This is, quite clearly, too bold a claim.

Nevertheless, Ascension Island did play an important role in imperial history, in environmental engineering and in extra-terrestrial exploration — if only to the moon. This role was defined by the island’s peculiar mixture of remoteness and centrality, the interplay of disconnection and connectivity. Taken together, this created a specific setting that NASA image G-66-9145 ingeniously captures and highlights: a setting of

global dis:connectivity.

[1] National Aeronautics and Space Administration, ‘Ascension Island. Manned Space Flight Network Station’ (Goddard Space Flight Center, November 1967).

[2] Peter Agnos,

The Queer Dutchman (New York: Green Eagle Press, 1976).

[3] Menno Schilthuizen,

The Loom of Life. Unravelling Ecosystems (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2008), 125.

[4] National Aeronautics and Space Administration, ‘Ascension Island. Manned Space Flight Network Station’.

[5] National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

bibliography

Agnos, Peter.

The Queer Dutchman. New York: Green Eagle Press, 1976.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration,

Ascension Island Manned Space Flight Network Station, Goddard Space Flight Center, November 1967.

Schilthuizen, Menno.

The Loom of Life. Unravelling Ecosystems. Berlin-Heidelberg: Springer, 2008.

citation information

Continue Reading

A warm welcome to our new fellow Franziska Windolf who recently joined global dis:connect.

A warm welcome to our new fellow Franziska Windolf who recently joined global dis:connect.

Nomadic Camera. Photography, Displacement and Dis:connectivities

Nomadic Camera. Photography, Displacement and Dis:connectivities

A warm welcome to our new fellow Gabriele Klein who joins the Kolleg until autumn 2023.

A warm welcome to our new fellow Gabriele Klein who joins the Kolleg until autumn 2023.

Our fellow Kevin Ostoyich is giving a talk on Jewish refugees in Shanghai during the Second World War at the Begegnungsstätte Neue Synagoge in Erfurt (address:

Our fellow Kevin Ostoyich is giving a talk on Jewish refugees in Shanghai during the Second World War at the Begegnungsstätte Neue Synagoge in Erfurt (address:  A warm welcome to our new fellow Siddharth Pandey who joins the Kolleg until autumn 2023.

A warm welcome to our new fellow Siddharth Pandey who joins the Kolleg until autumn 2023.

A warm welcome to our new fellow Viviana Iacob who joins the Kolleg until autumn 2023.

Viviana Iacob is a theatre historian with a background in the history of art and theatre as well as Shakespeare studies. Her work relies on interdisciplinary methodologies and a trans-regional reading of post-war Eastern European theatre cultures and focuses on the global history of illiberal regimes during the Cold War and its aftermath. She has conducted archival research on the history of international theatre organisations and their role in globalising state-socialist cultures after 1945 in Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, Germany and France. Between May 2020 and July 2022 she was a Humboldt fellow, which gave her the opportunity to develop a monograph that explores the circulations and contributions of Eastern European theatre practitioners in international organisations. These trajectories of expertise reflect North-East-South entanglements and networks forged at the intersection of Cold War politics, decolonisation and globalisation.

Project: Alternative theatre globalisations: internationalising illiberal regimes since the late 1970s

The project re-historicises the relationship between globalisation and theatre by analysing the practices of internationalisation and cultural diplomacy deployed by illiberal regimes before and after 1989. The project identifies trans-regional dis:connections that differ from those converging on or emerging from the West. The research combines the study of late-Cold War globalisation processes with a focus on international theatre organisations. By highlighting alternative globalities, the project addresses patterns of integration and disintegration that have been marginalised by entrenched Western-centric discourses on recent histories of theatre.

To read a interview with Viviana, click

A warm welcome to our new fellow Viviana Iacob who joins the Kolleg until autumn 2023.

Viviana Iacob is a theatre historian with a background in the history of art and theatre as well as Shakespeare studies. Her work relies on interdisciplinary methodologies and a trans-regional reading of post-war Eastern European theatre cultures and focuses on the global history of illiberal regimes during the Cold War and its aftermath. She has conducted archival research on the history of international theatre organisations and their role in globalising state-socialist cultures after 1945 in Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, Germany and France. Between May 2020 and July 2022 she was a Humboldt fellow, which gave her the opportunity to develop a monograph that explores the circulations and contributions of Eastern European theatre practitioners in international organisations. These trajectories of expertise reflect North-East-South entanglements and networks forged at the intersection of Cold War politics, decolonisation and globalisation.

Project: Alternative theatre globalisations: internationalising illiberal regimes since the late 1970s

The project re-historicises the relationship between globalisation and theatre by analysing the practices of internationalisation and cultural diplomacy deployed by illiberal regimes before and after 1989. The project identifies trans-regional dis:connections that differ from those converging on or emerging from the West. The research combines the study of late-Cold War globalisation processes with a focus on international theatre organisations. By highlighting alternative globalities, the project addresses patterns of integration and disintegration that have been marginalised by entrenched Western-centric discourses on recent histories of theatre.

To read a interview with Viviana, click  A warm welcome to our new guest Martin Puchner who joins the Kolleg until late spring 2023.

Martin Puchner has worked on such disparate topics as modernist closet dramas, revolutionary manifestos, Platonic dialogues, a history of world literature, environmental storytelling and Rotwelsch, the secret language of Central Europe. Having studied at the universities of Konstanz and Bologna, he pursued these topics at Columbia and Harvard, with shorter stints at Cornell, the Berlin Institute for Advanced Study, the New York Public Library and the American Academy. He occasionally attempts to bring the humanities to the attention of a larger public with op-eds, book reviews, essays, anthologies and open online courses.

At global dis:connect, Martin will expand his forthcoming history of culture, entitled Culture: the story of us, from cave art to K-pop, into a textbook introduction to the arts and humanities. The work focuses on mechanisms of transmission, with particular emphasis on interruption, misreading, appropriation and — of course — global dis:connections.

A warm welcome to our new guest Martin Puchner who joins the Kolleg until late spring 2023.

Martin Puchner has worked on such disparate topics as modernist closet dramas, revolutionary manifestos, Platonic dialogues, a history of world literature, environmental storytelling and Rotwelsch, the secret language of Central Europe. Having studied at the universities of Konstanz and Bologna, he pursued these topics at Columbia and Harvard, with shorter stints at Cornell, the Berlin Institute for Advanced Study, the New York Public Library and the American Academy. He occasionally attempts to bring the humanities to the attention of a larger public with op-eds, book reviews, essays, anthologies and open online courses.

At global dis:connect, Martin will expand his forthcoming history of culture, entitled Culture: the story of us, from cave art to K-pop, into a textbook introduction to the arts and humanities. The work focuses on mechanisms of transmission, with particular emphasis on interruption, misreading, appropriation and — of course — global dis:connections.

A warm welcome to our new fellow Anna Grasskamp who joins the Kolleg until late summer 2023.

Anna Grasskamp is a lecturer in art history at the University of St Andrews. She has authored Art and Ocean Objects of Early Modern Eurasia. Shells, Bodies, and Materiality (Amsterdam University Press, 2021) and Objects in Frames: Displaying Foreign Collectibles in Early Modern China and Europe (Reimer, 2019). Her articles have appeared in Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics, Renaissance Studies and other journals. Anna is a subject editor at the review journal SEHEPUNKTE and a member of the editorial boards of the book series Global Epistemics and the Journal for the History of Knowledge.

Project:

Trash as treasure: value disconnections and the recycling of Chinese matter in art and design, 1500–2020

Recycling materials ‘made in China’ has a short history in the daily practices of middle-class households, but a long history in global art and design. Chinese natural resources, such as rare-earth metals used in digital devices and commodities like porcelain made of Chinese clay, have been pivotal to material, technological and artistic exchanges between Europe and Asia since early modernity. This project investigates art and design as fields of pioneering research in which strategies to reuse Chinese matter were developed centuries before the term ‘recycling’ – as we use it today – was adopted. It researches material flows of garbage in relation to disrupted material value systems associated with trash. Disruptions take place across cultural boundaries that allow for radical changes in systems of material evaluation (e.g. enabling the perception of ‘trash as treasure’) and through transcultural artistic research, which reuses and re-evaluates seemingly ‘meaningless’ garbage by turning it into multi-million-dollar art installations and prized design innovations. The project offers a non-hegemonic history of art and design, which researches urban hubs and rural ecologies, the works of artists and artisans, as well as the products of craftsmen and factory workers across social, historic and cultural divides.

A warm welcome to our new fellow Anna Grasskamp who joins the Kolleg until late summer 2023.

Anna Grasskamp is a lecturer in art history at the University of St Andrews. She has authored Art and Ocean Objects of Early Modern Eurasia. Shells, Bodies, and Materiality (Amsterdam University Press, 2021) and Objects in Frames: Displaying Foreign Collectibles in Early Modern China and Europe (Reimer, 2019). Her articles have appeared in Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics, Renaissance Studies and other journals. Anna is a subject editor at the review journal SEHEPUNKTE and a member of the editorial boards of the book series Global Epistemics and the Journal for the History of Knowledge.

Project:

Trash as treasure: value disconnections and the recycling of Chinese matter in art and design, 1500–2020

Recycling materials ‘made in China’ has a short history in the daily practices of middle-class households, but a long history in global art and design. Chinese natural resources, such as rare-earth metals used in digital devices and commodities like porcelain made of Chinese clay, have been pivotal to material, technological and artistic exchanges between Europe and Asia since early modernity. This project investigates art and design as fields of pioneering research in which strategies to reuse Chinese matter were developed centuries before the term ‘recycling’ – as we use it today – was adopted. It researches material flows of garbage in relation to disrupted material value systems associated with trash. Disruptions take place across cultural boundaries that allow for radical changes in systems of material evaluation (e.g. enabling the perception of ‘trash as treasure’) and through transcultural artistic research, which reuses and re-evaluates seemingly ‘meaningless’ garbage by turning it into multi-million-dollar art installations and prized design innovations. The project offers a non-hegemonic history of art and design, which researches urban hubs and rural ecologies, the works of artists and artisans, as well as the products of craftsmen and factory workers across social, historic and cultural divides.