In

Blog 2022

roland wenzlhuemer

Crises and globalisation

Etymologically speaking, crises are dramatic — perhaps even life-threatening — phenomena.

[1] They are inflection points. And as such, they are supposed to be temporary. So far in this still-young 21

st century, individual crises might seem temporary, but the state of crisis that plagues society more broadly seems all too permanent. For years now, we have been enduring a constant, deeply transformative state of emergency, consisting of overlapping economic and social crises.

[2]

Think back. Not long after the horrific attacks of September 11

th and the subsequent global war on terror, much of the world suffered a dire financial crisis. Just as the global economy gradually started to recover, public consciousness began to grasp the reality of climate change, whose socio-economic effects are becoming ever harder to ignore. As people slowly started engage with the climate crisis, it was overshadowed in the mid-2010s — at least in Europe — by the ‘refugee crisis’ and the fears it evoked. While both of these issues remain with us, they have faded into the background, outshined by the ominous and mercurial COVID crisis.

For all their overlap and interrelations, these crises, of course, display important differences: they all move at their own paces and in their own temporalities; they all affect different regional epicentres, which can change over time; they all manifest themselves in our everyday lives in their own ways; they all engage particular collective and individual fears; and each one poses its own range of ethical dilemmas.

There is one thing, however, that all these crises have in common:

they are deeply embedded in processes of globalisation, past and present.

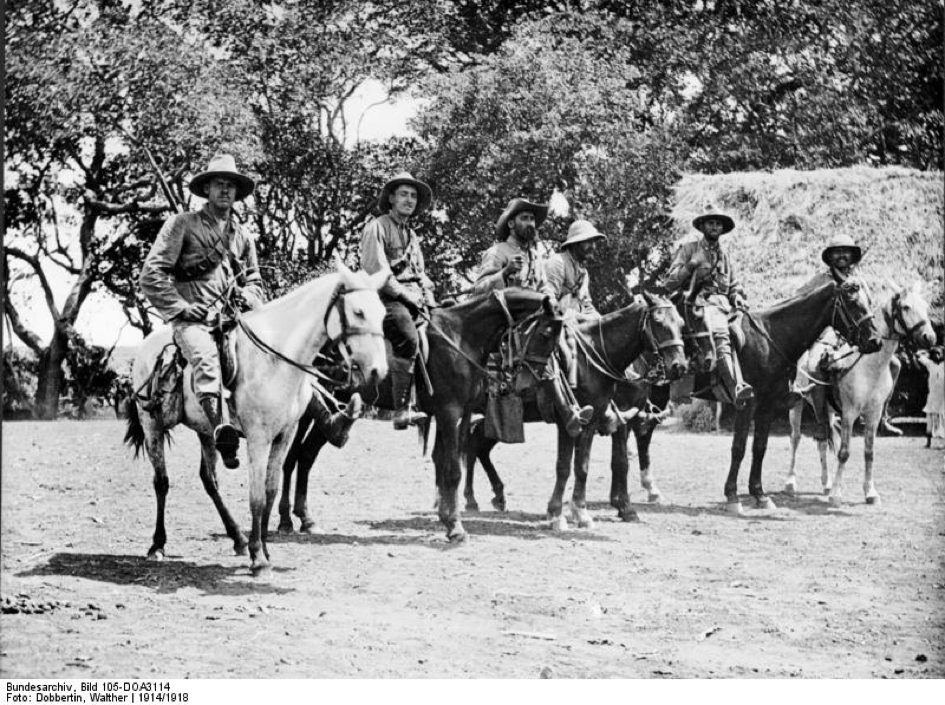

Politically and religiously motivated terrorism, for example, is nourished by a complex global web of geopolitical ambitions and cultural antagonisms extending back at least to the days of triumphant European imperialism.

[3]

In economics, the subprime mortgage crisis in the USA in 2008

permeated global capital markets along countless reciprocal ties.

A regional real-estate bubble rapidly induced a global banking crisis.

In ecology, human-induced climate change is inseparable from the history of industrialisation and consumerism. Rapid growth, interregional mobility and the global division of labour are what fuels it. Climate change pays no heed to human boundaries, national or otherwise. It is among the few literally global phenomena.

Another, surely, is COVID-19. In early 2020, the virus spread, well

, virulently around the entire planet along the routes of global mobility networks.

Dense, interconnected, global networks are what all these crises share. They would be unthinkable without processes of worldwide exchange that have grown over the last 200 years or so. These crises make the scope and depth of global networks uniquely palpable.

Ripples of disconnection

Another common characteristic, however, is an often-overlooked aspect of globalisation: disruptive phenomena that

corrode networks. Connection and *dis*connection, linkage and isolation, entanglement and disentanglement in constant oscillation. Each is unthinkable without the other.

Such co-relations have become undeniably tangible in the COVID crisis. In the early days of the pandemic, many borders were closed and tight regulations were imposed on interregional travel. Curfews and access restrictions became common, and large gatherings were outright forbidden. Schools have done their best with ‘distance learning’. Cultural events have sought refuge in cyberspace. Quarantine rules curtailed the production and transportation sectors, which has hamstrung global supply chains. The permeation of global networks into daily life is what makes the COVID crisis so disruptive.

The interplay between entanglement and disentanglement is apparent beyond the COVID crisis. Other recent events, like the Brexit process and the

Ever Given, that fateful ship that ran aground in the Suez Canal and interrupted a key global shipping thoroughfare, are of the same stripe.

Even the overwhelming global cataclysms I mentioned above display dynamics of entanglement and disentanglement on closer inspection. The Great Recession began when the US real-estate bubble popped. Thus, there is an immediate tension between immobile, local objects (ie, buildings) and their valuation in volatile, deeply interconnected financial markets. The interplay is even more pronounced when considering the cause of the crisis. Trust — a primal type of connection — evaporated, and its lack rippled throughout the dense network of capital flows.

The climate crisis, whose creeping, surreal progress unmistakably carries a disconnective element within it, is similar. Attempts to combat climate change have been thwarted principally by insufficient will and the ineffectuality of international cooperation. In the face of the inherently global character of climate change, parochial interests and structures have largely trumped global initiatives.

Global refugee migrations exemplify more than just human mobility. They are also characterised by prejudicial treatment, closed borders, long delays, strict asylum regimes and even

brutal ‘pushbacks’. Here, too, connective and disconnective aspects reciprocally constitute each other.

These crises are stories not only of global linkages; they also reveal disruptive, disconnective aspects of globalisation. It’s the interplay between them that defines such processes. At

global dis:connect, our focus is precisely this interplay, which we refer to as dis:connectivity. This concept enables new perspectives on past and current processes of global interlinkage, and it might even help us to better understand the crises that result.

Global crises touch everyone. Us too.

We certainly hope that dealing with global dis:connectivity on a scholarly level will help us to cope with all the challenges we face in trying to found an international research centre in the middle of the COVID pandemic. There is indeed a certain irony in the fact that the Centre’s administration regularly confronts the interplay of connection and disconnection. Though we strive to make the Centre a locus of collaborative research and dialogue, we haven’t been able to meet in recent months as much as we’d like. We also endeavour to foster conversations between our international fellows and our in-house researchers, but travel restrictions have forced us to delay some fellows’ visits or to declare parts of their visits strictly ‘remote’.

We are trying to engage with the broader public, which is no small trick when large gatherings are inadvisable or prohibited. We’re trying to offer our fellows the best possible working conditions, which is not easy when the requisite articles and devices have been on order for months. And yet, we converse. We research. We share. And we organise. But we must also adapt. Even in the everyday life of the Centre, a new and fascinating interplay between global linkage and disruption manifests itself. So, dis:connectivity is something we’re not only

researching at the Centre; we’re actively

experiencing it.

[1] Reinhart Koselleck, ‘Krise’, in Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe: Historisches Lexicon zur politisch-sozialen Sprache in Deutschland, vol. 3, 8 vols (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 1972), 617–50.

[2] Thomas Macho, ‘Krisenzeiten: Zur Inflation eines Begriffs’, Geschichte der Gegenwart (blog), 31 May 2020, https://geschichtedergegenwart.ch/krisenzeiten-zur-inflation-eines-begriffs/.

[3] Sylvia Schraut, Terrorismus und politische Gewalt (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2018); Carola Dietze, Die Erfindung Des Terrorismus in Europa, Russland Und Den USA 1858-1866 (Hamburg: Hamburger Edition, 2016).

bibliography

Brunner, Otto, Werner Conze, and Reinhart Koselleck, eds. ‘Krise’. In

Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe. Historisches Lexikon zur politisch-sozialen Sprache in Deutschland. Band 3: H-Me, 617–50. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 1982.

Dietze, Carola.

Die Erfindung des Terrorismus in Europa, Russland und den USA 1858-1866. Hamburg: Hamburger Edition, 2016.

Macho, Thomas. ‘Krisenzeiten: Zur Inflation eines Begriffs’.

Geschichte der Gegenwart (blog), 31 May 2020. https://geschichtedergegenwart.ch/krisenzeiten-zur-inflation-eines-begriffs/.

citation information

This post has also appeared in issue 1.1 of our in-house journal, static.

Wenzlhuemer, Roland. ‘Crisis and Dis:Connectivity’. Static. Thoughts and Research from Global Dis:Connect, 2022.

Continue Reading

The center extends a warm welcome to Sujit Suvasundaram (Cambridge) who joins as a new research fellow for the year 2022.

Sujit has taken a circuitous path to his current post as Professor of World History and Director of the Centre of South Asian Studies in Cambridge. Bouncing between the Asia-Pacific region and Europe, he has left his mark on imperial history, oceanic history, cultural history, and the history of science. This path has taken him through the LSE, the EHESS in Paris, the Universities of Singapore and Sydney, and the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. During his fellowship with us in Munich, Sujit will be focusing on the long history of Colombo. He is interested in the challenges of building a city such as this, at the centre of the Indian Ocean, in a marshy terrain, and the labour and community formation that met such an environmental challenge. He will be developing his perspective on connection as an unstable practice, especially when tied to capitalism and empire, because of its potential to segment and divide places and people. He is also interested in the art and visual practice surrounding this city and what it tells us of how globalisation is visualised and propagandised.

The center extends a warm welcome to Sujit Suvasundaram (Cambridge) who joins as a new research fellow for the year 2022.

Sujit has taken a circuitous path to his current post as Professor of World History and Director of the Centre of South Asian Studies in Cambridge. Bouncing between the Asia-Pacific region and Europe, he has left his mark on imperial history, oceanic history, cultural history, and the history of science. This path has taken him through the LSE, the EHESS in Paris, the Universities of Singapore and Sydney, and the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. During his fellowship with us in Munich, Sujit will be focusing on the long history of Colombo. He is interested in the challenges of building a city such as this, at the centre of the Indian Ocean, in a marshy terrain, and the labour and community formation that met such an environmental challenge. He will be developing his perspective on connection as an unstable practice, especially when tied to capitalism and empire, because of its potential to segment and divide places and people. He is also interested in the art and visual practice surrounding this city and what it tells us of how globalisation is visualised and propagandised.

Burcu Dogramaci, art historian and one of the Kolleg’s directors, spoke on “Pandemische Kamera: Gefahr und Schutz im fotografischen Bild” at the conference “Digital Realities: Political Imagery and Mediatized Nature in Times of COVID-19” on 15 December 2021.

Burcu Dogramaci, art historian and one of the Kolleg’s directors, spoke on “Pandemische Kamera: Gefahr und Schutz im fotografischen Bild” at the conference “Digital Realities: Political Imagery and Mediatized Nature in Times of COVID-19” on 15 December 2021.

Roland Wenzlhuemer, historian and one of the Kolleg’s directors, delivered the opening lecture for the Master program "Global History at the University of Bayreuth. He spoke on “Ships' ballast in Global History”.

Roland Wenzlhuemer, historian and one of the Kolleg’s directors, delivered the opening lecture for the Master program "Global History at the University of Bayreuth. He spoke on “Ships' ballast in Global History”. On 8 November, Christopher Balme, theatre scholar and one of the Kolleg’s directors, spoke on “Perpendicular Theatres and Mammy Wagons: The infrastructure of tragedy in post-independence Nigeria. Workshop “Traveling Tragedy”” at the University of Konstanz.

On 8 November, Christopher Balme, theatre scholar and one of the Kolleg’s directors, spoke on “Perpendicular Theatres and Mammy Wagons: The infrastructure of tragedy in post-independence Nigeria. Workshop “Traveling Tragedy”” at the University of Konstanz.

On 5 November, Burcu Dogramaci, art historian and one of the Kolleg’s directors, presented her work at the Jahrestagung des Verbands Österreichischer Kunsthistorikerinnen und Kunsthistoriker in Vienna. She spoke on “Kunst handeln. Galeristinnen der Moderne im Einsatz für die Kunst ihrer Zeit“.

On 5 November, Burcu Dogramaci, art historian and one of the Kolleg’s directors, presented her work at the Jahrestagung des Verbands Österreichischer Kunsthistorikerinnen und Kunsthistoriker in Vienna. She spoke on “Kunst handeln. Galeristinnen der Moderne im Einsatz für die Kunst ihrer Zeit“.

We are proud to report that our future fellow Sujit Sivasundaram’s latest book ‘Waves Across the South: A New History of Revolution and Empire’ wins this year’s British Academy Book Prize for Global Cultural Understanding. Sujit, who will join the Kolleg as a fellow in January, is a historian at the University of Cambridge. In his book, he radically shifts perspective and re-thinks British colonial history as seen from the southern seas. In doing so, he presents a much-needed adjustment in our Eurocentric imagination of the Age of Revolutions.

We are proud to report that our future fellow Sujit Sivasundaram’s latest book ‘Waves Across the South: A New History of Revolution and Empire’ wins this year’s British Academy Book Prize for Global Cultural Understanding. Sujit, who will join the Kolleg as a fellow in January, is a historian at the University of Cambridge. In his book, he radically shifts perspective and re-thinks British colonial history as seen from the southern seas. In doing so, he presents a much-needed adjustment in our Eurocentric imagination of the Age of Revolutions.