Highland living and the evolving textures of architectural identity in the Himalayas

siddharth pandey

Ask anyone in India to quickly draw a ‘scenery’, and most people would intuitively scribble two or more triangles in the background signifying a mountain range, a thick bar of waterfall gushing from somewhere in between that suddenly transforms into a river, and finally, a single-story house with a pitched roof in the foreground, basking in its idyllic surroundings. This is despite the fact that most of the population does not dwell in the highlands but plains. Nor do contemporary buildings exhibit slanting roofs or one-floor plans as regularly as in the past. This ‘commonplace’, archetypal idea of a scenery for 1.4 billion people might articulate a nostalgic, even childish approach to how imagined landscapes are collectively framed. But therein lies its significance too. For such scenery effortlessly illustrates the notion of ‘ecology’ in its most elemental, etymological form. As a portmanteau of the Greek words oikos (meaning ‘house’) and logia (meaning ‘study of’), ecology points to the study of human dwelling. Today, though we largely use the term for its ‘natural’ connotation, the original import of ecology prompts us to consider both human dwelling and the natural environment in essentially interlinked terms. So while the house of the scenery may seemingly occupy the centre stage, its roof also mirrors the slope of the background mountains, literally representing the ‘pinnacles’ of imagination (pun intended). Architecture’s affinity with the natural environment becomes apparent early to people who grow up in the Himalayas, especially from observing the many ancient villages and small towns strewn across the landscape. Historians of the Himalayas, like Chetan Singh and Aniket Alam, have argued that what sets traditional mountain societies apart from other subcontinental cultures is their considerable dependence on the natural topography.[1] While in the plains, owing to the land’s flatness, one could build vast, multi-storied structures; in the hills, this feature must inevitably shift. With habitable spaces varying anywhere between 400 to 4000 meters above the sea level, the physicality of mountains has always played a decisive role in determining the materiality of human-made dwellings. Thus, a ‘mountain home’ in its prototypical sense necessarily implies a balance between the natural and cultural, an equilibrium that is now fast disappearing under the ill-conceived developments of modernity.*

The idea of ‘dwelling’ or ‘home’ is generally considered to be precious, even sacred, despite the fact it may mean different things to different people. Amply romanticised in culture since the beginnings of history and intrinsically linked to the notions of belonging and identity, home indexes the embodied ideals of comfort, safety and bonhomie. Homes make us as much as we make them. While the entity of the house is possibly the most obvious transmitter of home, the environment which the house finds itself in — a neighbourhood, a locality, a village, a town, a city, a landscape — contributes equally, if not more, to the character and ambience of home. Hilly regions generously and evocatively lend themselves to this aspect, because the outside and inside are always in conversation with each other. Views from one’s windows matter as an essential part of the house itself, as does the last ray of the sun peeling away from the flank of a distant hill. In this way, the word pahaad (Hindi for mountains) routinely become synonymous with ghar (Hindi for home). India being a largely tropical country dominated by plains, heights continue to define a much-loved and often-revered ‘other’. Countless mountains and summits serve as homes of local gods and goddesses, and hill people themselves express great pride and satisfaction in the distinctiveness of their landscape. If the recent ‘Happiness Surveys’ of India’s best states are anything to go by, then the regions bagging the top spots would only prove the link between mountain living and well-being further, given that they are located in the Himalayas.[2] Two ideas frequently characterise the popular perception of mountain life. One is the idealised image of dwelling in a salubrious, scenic setting. The other points to a ‘toughness of spirit’, a hallmark of all mountain societies, given the undulating terrains and demanding weather conditions that must be navigated daily. From a critical viewpoint, it is tempting to align the first image with the tourist gaze and the second with the ‘actual life’ of hill people. But while there is some truth in this opinion, the binary doesn’t exist in absolute terms. Notwithstanding their hardships, hill people have long been aware of inhabiting a space that is vastly different from lowland cities, a space that invariably demands sensitive attunement towards nature, both aesthetically and work-wise. Such attunement doesn’t only include the staple professions of agriculture, horticulture and pastoralism, but also the practices of architecture and spatial planning, which have evolved over many centuries in concert with the natural surroundings.*

Among the most well-known traditional building techniques in the Himalayas are the Kath-Kuni, Koti Banal and Dhajji-Dewari styles of the Middle Himalayas, as well as the mud-brick, slate-roof style of the Lower Himalayas. Both the Kath-Kuni and the Koti-Banal methods are variations of the Cator-and-Cribbage template, which have evolved over hundreds of years in the upper reaches of the mountains. In Kath-Kuni, which literally translates as ‘wooden corner’, alternate horizontal layers of stone and wooden beams are stacked together without any cementing materials to create long-lasting walls, which often support intricately carved overhanging balconies to let sunshine in. Similar to the Kath-Kuni is the Koti-Banal style, which derives its name from a village in the state of Uttarakhand. The only major exception here is that we sometimes find several vertical timber beams passing through the horizontal wooden beams for added fortification. Tellingly, these templates were not only used for creating human dwellings but also shrines and shelters for gods, goddesses and cattle. And like most indigenous architecture, the buildings were made by the very people who lived in them or used them in some capacity. In both Kath-Kuni and Koti-Banal, the ground floor is reserved for cattle, the middle for fodder and the upper most for human habitation. Since it gets extremely cold during winters, the cattle can’t be left outside but are drawn into the folds of the walls, and their flatulence and belching helps keep the overall structure warm. The lack of cement and the use of sockets for fixing stone and wood horizontally also ensures superb seismic resistance, given that the whole of the Himalayas lies in an earthquake-prone region. In the lower and more sprawling valleys, we again witness a perfect synthesis of traditional human vision and environment. Here, the mud-bricked, slate-roofed building style evolves out of the rich presence of clay, slate and pine and bamboo trees. The whole process is contingent on natural forces. For instance, the bricks are made of a mixture of soil, sieved mud, water and straw, which is pugged with the help of an ox or cow over several days. Cow dung itself is a handy building material, as its ability to reduce the sun’s harmful radiation allows it to be converted into a coating that is plastered all over the floor and walls. Along with this, a layer of neem and clove oil is applied to keep the termites away. The building techniques used for cattle residences (often placed along the courtyard) are the same as those used for humans. In the past, the low-raised floors above the cattle pens (otherwise used only for storing fodder) would doubly serve as shelters for nomadic pastoralists during their seasonal migrations from the higher Himalayas to the lower valleys. Another building technique, Dhajji-Dewari, is a variation of the wattle-and-daub template widespread all over Europe, Africa and other parts of Asia. Consisting of an infill of clay, stone and pine needles that form ‘patched quilt walls’ on an overall timber-caged framework, Dhajji-Dewari was popularised during the colonial times. Owing to its resemblance to Victorian Neo-Tudor style of building, the British era architects birthed numerous kinds of hybrid designs at the intersection of Himalayan and European aesthetics, which were again a fine blend of sturdiness, elegance and seismic resistance. All these building styles appeared to stem from the earth, so that instead of seeming like an artificial outcrop, they gave the impression of growth and natural continuity.

Fig. 1: Siddarth Pandey. Hidimba Devi Temple, an example of 'Kath-Kuni' architecture in the Kullu Valley, Himachal Pradesh.

Fig. 2: Siddarth Pandey. Mud and slate houses in the Kangra Valley, Himachal Pradesh.

Fig. 3: Siddarth Pandey. Cedar House, an example of 'Dhajji-Neo-Tudor' hybrid architecture in Shimla, Himachal Pradesh.

*

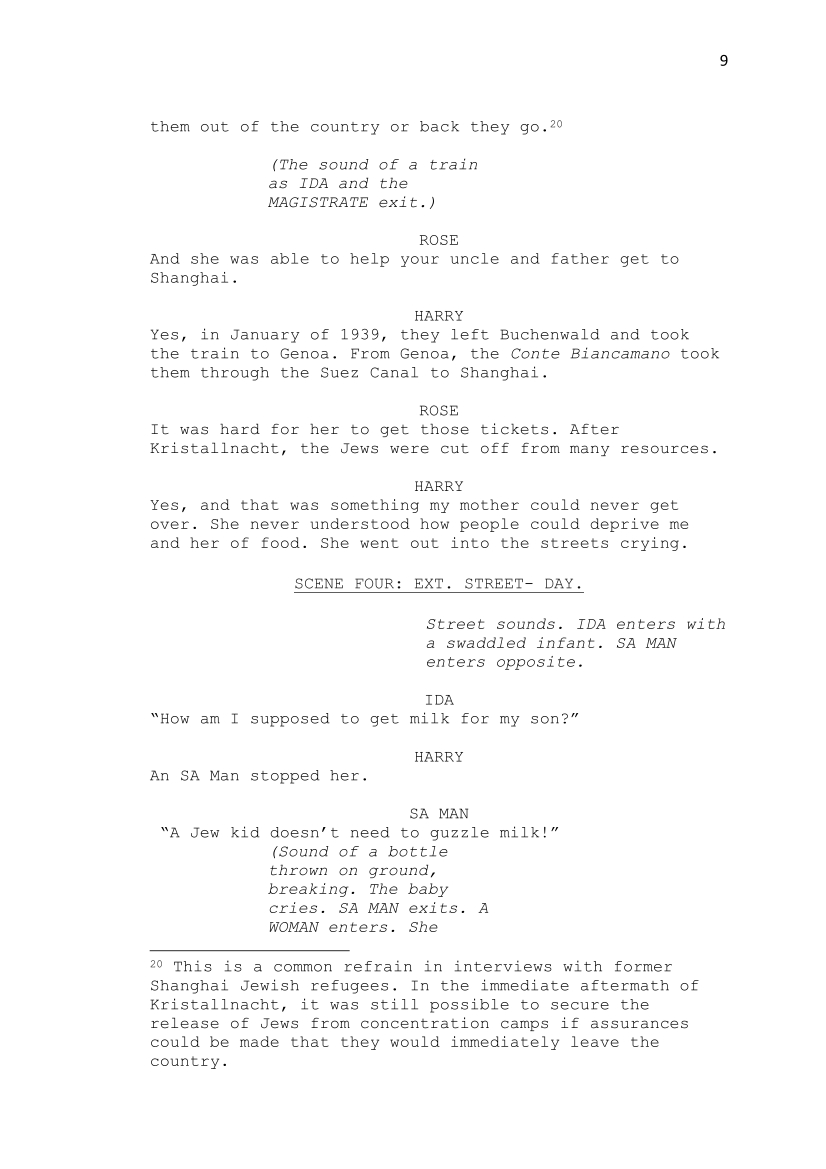

It was around three to four decades into Independence that hill societies first started experiencing a drastic change in their architectural ethos. Even as the inauguration of cement factories, high-rise structures and newer advancements in building technology ostensibly ushered in novel symbols of modern development, their indiscrete application across vastly varying geographies invariably augured trouble and imbalance. This was especially true for the Himalayan states, where no one had ever dwelled in buildings above a few stories high and devoid of local materials. After 1947, architecture and urban planning more than any other area of human concern couldn’t come up with a robust, sustainable and widescale creative vision for itself, the disastrous consequences of which are felt to this day. India’s foremost writer on architecture, Gautam Bhatia, observes that in the Independence era, ‘little has changed in Indian planning, urbanism, architecture or ways of thinking. No attempt has been made to define, in a common language, the kind of architecture we would like to live in’. He raises concern over ‘the civic disorder of places confounded by squalid government construction, extravagant private commerce and mounting slums’, and laments how, ‘in the absence of an institutional culture, architecture can only be a private inconsequential activity. People build on whim, day in and day out, adding personal appendages of construction to new or previous assemblies, adding to the jumbled mix’.[3] It is this ‘jumbled mix’ that overwhelmingly defines the built character of India, including the hills, where the majority of new buildings and city plans are indistinguishable from their lowland counterparts. Not only does this development quash the historical and visual sense of a mountainous terrain by contradicting its gradually-evolved ethos, it also fails in its promise of providing revolutionary alternatives to older ways of living. Most modern structures erected in hilly terrains hardly guard against any kind of natural calamities, whether earthquakes or floods. In late 2022, the popular pilgrimage town of Joshimath in Uttarakhand hit the national headlines for precisely these reasons, where almost all the houses developed cracks due to the sinking ground they stood on, which was itself constituted of loose landslip-mud. Joshimath now lies at the brink of complete collapse. More recently, in July 2023, the state of Himachal Pradesh witnessed its most calamitous flash floods in collective memory, and among the colossal damage were the houses, roads and other public infrastructure that had been recklessly constructed in the flood plains and along shaky, felled slopes, all within the last few decades. In another such example, many people complain of illnesses resulting out of the imprudent usage of cement and marble in the contemporary dwellings of the higher Himalayas, since they fail to insulate naturally against heat and cold earlier as do indigenously procured materials. In May 2022, Time Magazine carried a cover story that drew attention to this relationship between climate and health. Titled Western Architecture is Making India’s Heatwaves Worse, the piece shed light on how, after the economic liberalisation of the 1990s, a rapid shift away from climate-specific architecture started to define the Indian landscape, exacerbating the current climate crisis. The article rightly argued that the ‘shift was partly aesthetic; developers favored the glassy skyscrapers and straight lines deemed prestigious in the U.S. or Europe, and young architects brought home ideas they learned while studying abroad’.[4] But the title of the piece was partially disingenuous as well, since it cunningly put the entire onus of Indian architectural failure on the West. For one, the heading didn’t acknowledge that it was the Indian development model itself that approved of such ‘new’ ideas in the first place. Secondly, it also presented Western architecture through a monolithic lens, pitting it against the indigenously robust architecture of pre-Independent India, as if there was no indigenous architecture in the West. In truth, however, Western architectural templates have been mixed and merged with Indian styles for centuries, including within the Himalayas (the Dhajji-Dewari being one of many examples). Thus, instead of apportioning the blame solely to Western models, it is crucial to nuance our language of criticism. Bhatia is again instructive here, for while finding flaws in the implementation of Western models on a foreign landscape, he simultaneously draws attention to the quality and context in which this change started taking place. ‘Indian architecture’s moral dilemma’, he says, ‘is in fact all the more cruel for ensuring that any and all forms of carefully cultivated Indian practices are quietly buried under the debris of second rate foreign images’, the emphasis thus being on quality rather than inspiration. He adds that ‘unfortunately, whenever European Modernism was practiced in [independent] India, the architect was building in exile; mainstream architecture’s self-importance always fed on keeping the public in the dark’, highlighting therefore the lack of building ideology’s moral compunctions.[5] Put another way, an enabling, organic relationship between an independent public ethos and the practice of architecture never truly developed in independent India. This resulted in a strange skewing of creative and practical vision, to the extent that aggressive individualism became the order of the day. This is not to say that India hasn’t produced good architects in the postcolonial period. One has only to look at the inspiring works of world-renowned visionaries such as BV Doshi and Charles Correa, who have blended together a strong public sensibility with a sustainable Indian imagination. But given the largeness of the country, such examples are but a drop in the ocean, and Bhatia’s remarks thus hold true for India in general.*

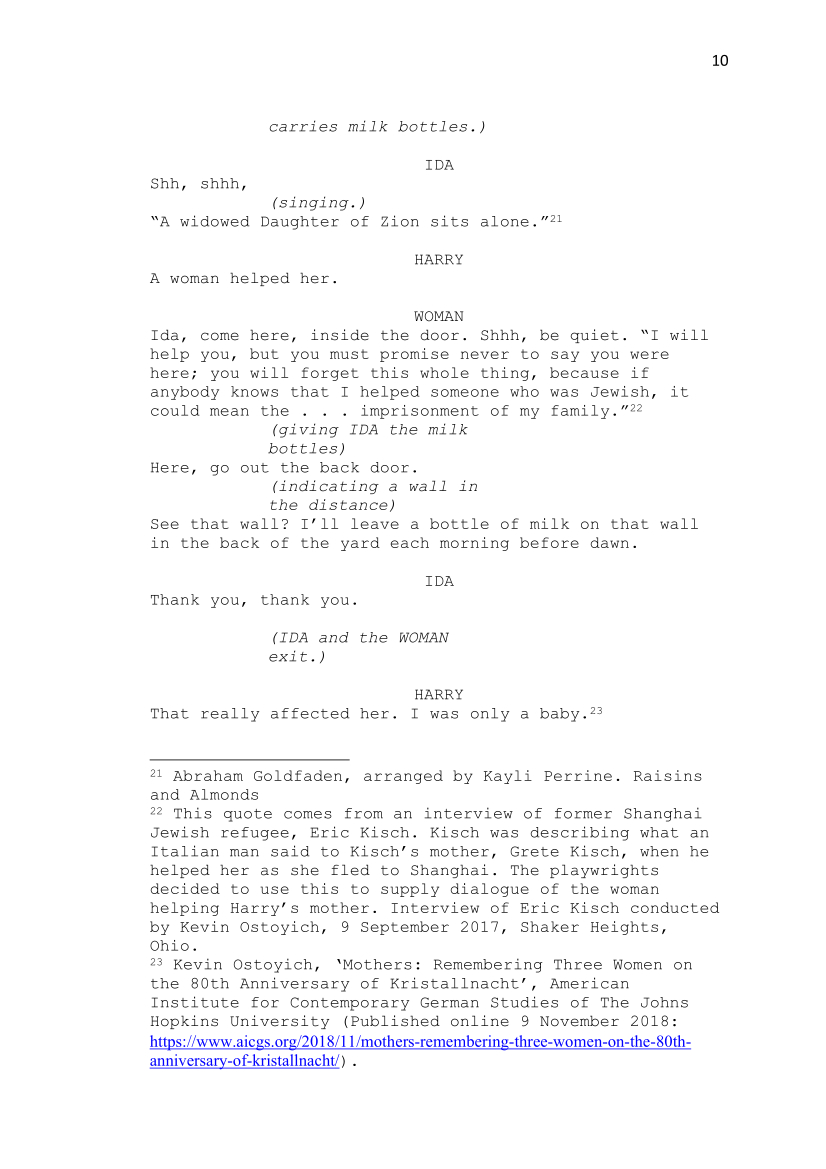

What is perhaps most tragic in the context of the Himalayas is the sheer indifference that has characterised the reception of public pleas and protests against such unscrupulous development. Despite the many voices in the region that have strongly stood against the barrage of shoddy novel projects, such endeavours have brazenly proceeded ahead. In the case of Joshimath, for instance, residents had started noticing cracks in their houses more than a year ago, before the crisis became a national headline. But every citizen intervention fell on deaf ears.[6] And as if the Joshimath crisis or the destructive flash floods weren’t enough as cautionary events, the Supreme Court of India gave the greenlight in January 2024 to open all the formerly designated ‘green areas’ of Himachal Pradesh’s capital Shimla for new construction.[7] This was done as part of the proposed 2041 Shimla Development Plan, under the pressure from the builders’ lobby, which wields astonishing power over politicians, bureaucrats and the judiciary. When the highest judicial body of the country is unable to protect the last remaining forested land, what hope can we have from anyone else? To quote the Himalayan anthropologist-activist Lokesh Ohri,Between such frustration and acceptance arises a ‘disconnect’ in every aspect of mountain life, a disconnect embodied most forcefully by architecture.the [postcolonial] state itself suffers a deep entrenchment of corporate interests and contractor lobbies. Sane voices in the mountain states are in no position to voice their concern over ‘development’ policies doled out from the Centre, gratefully accepting, and implementing whatever is on offer. At the Centre, too, there is little effort to hear voices on the ground, the ones that could narrate the truth of the crumbling Himalayas. There is no realization that what works in the plain-based states of the country may not work in the mountains.[8]

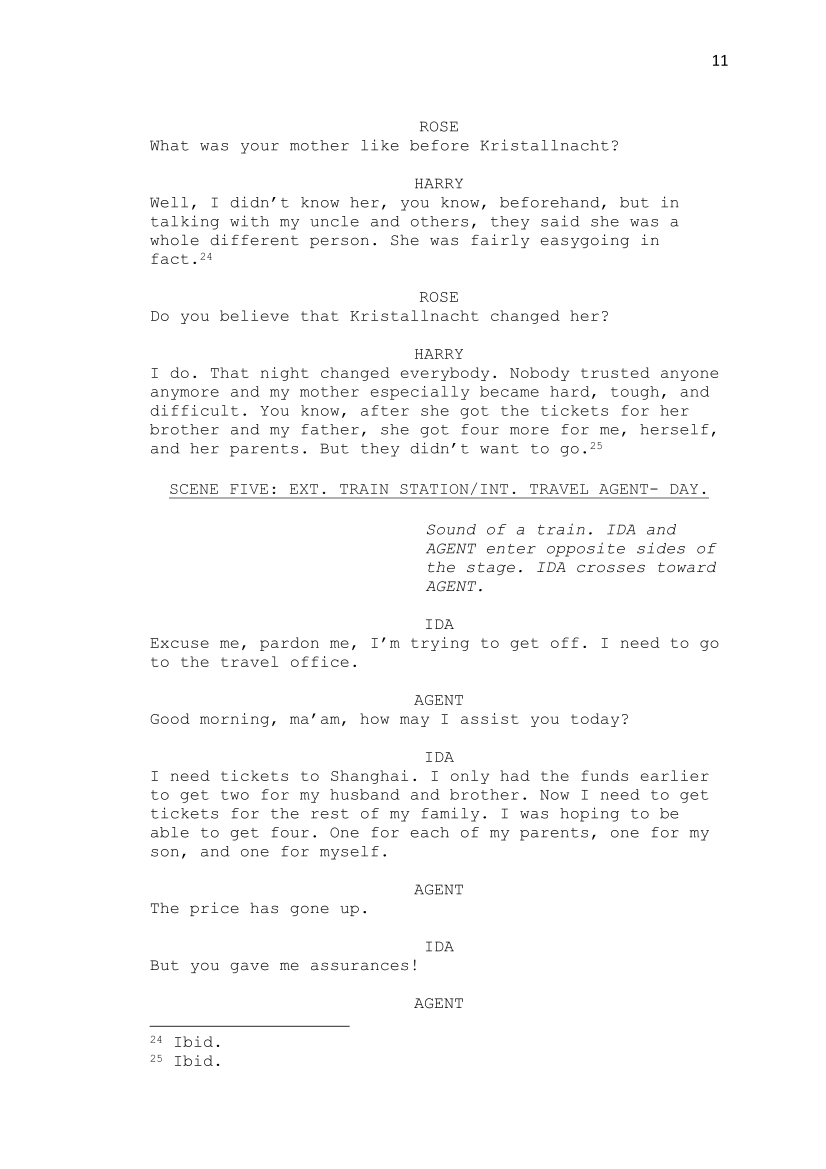

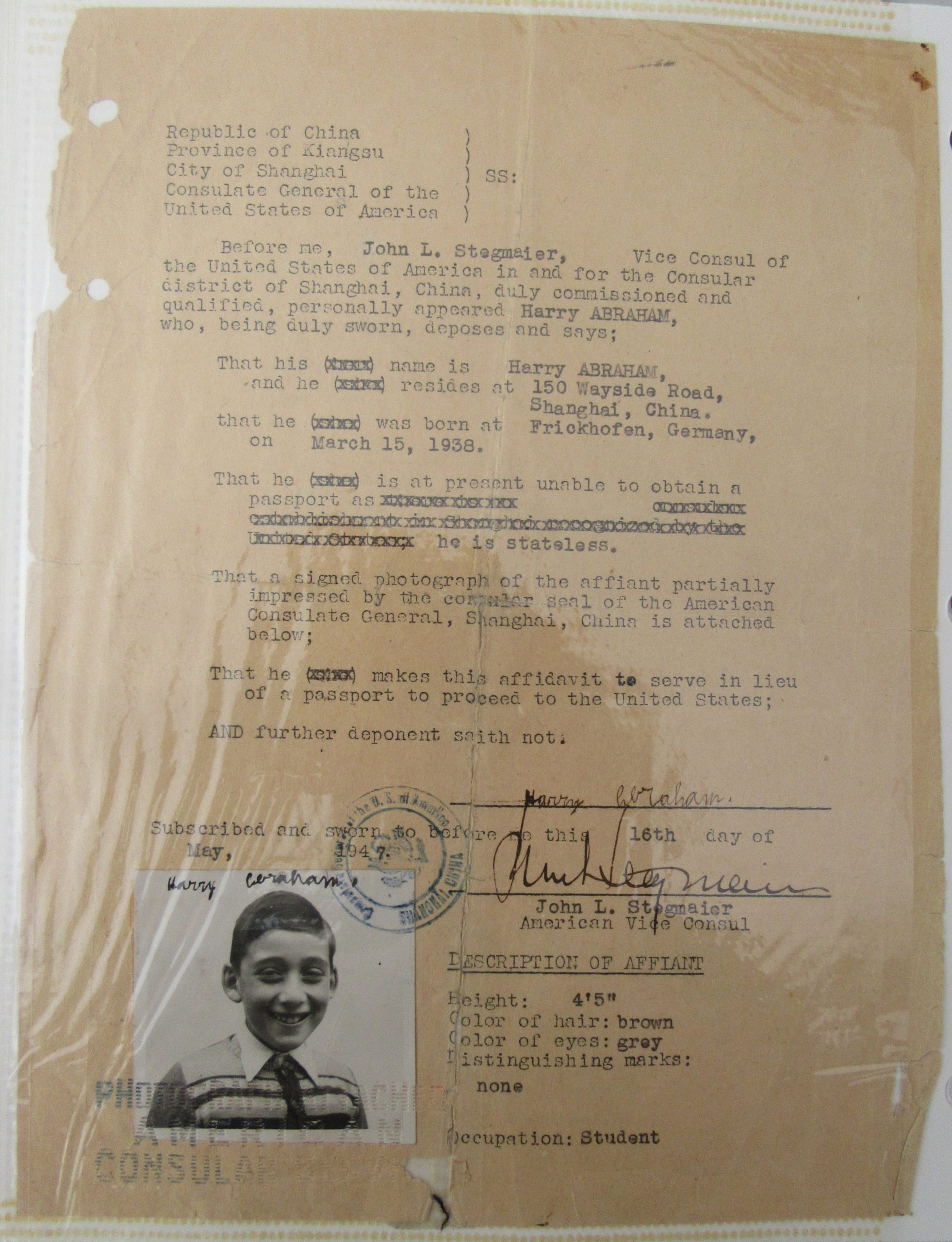

Fig. 4: Siddarth Pandey. Haphazard modern development in Mandi town, Himachal Pradesh.

*

In his well-regarded 2006 work The Architecture of Happiness, the philosopher Alain de Botton explores the many ways in which architecture is directly and indirectly related to the sphere of human emotions and nature, not just functionality. In a beautifully crafted moral statement, de Botton observes that ‘we owe it to the fields that our houses will not be the inferiors of the virgin land they have replaced. We owe it to the worms and the trees that the building we cover them with will stand as promises of the highest and most intelligent kinds of happiness’.[9] Likewise, we owe it to the Himalayas that the human endeavours we subject them to do not evolve as cruel forms of domination but rather as sensitive dialogues between the desires of men and the destiny of mountains.[1] See Chetan Singh, Natural Premises: Ecology and Peasant Life in the Western Himalaya 1800-1950 (New Dehli: Oxford University Press, 1998); Aniket Alam, Becoming India: Western Himalayas Under British Rule (New Dehli: Cambridge University Press, 2008). [2] Reya Mehrotra, 'What makes Himachal Pradesh the happiest state in India', The Week, 23 April 2023, https://www.theweek.in/theweek/cover/2023/04/14/what-makes-himachal-pradesh-the-happiest-state-in-india.html#:~:text=It%2C%20therefore%2C%20comes%20as%20no,did%20so%20last%20year%2C%20too. [3] Gautam Bhatia, 'Without architecture', Seminar, no. 722 (2019). https://www.india-seminar.com/2019/722/722_gautam_bhatia.htm. [4] Ciara Nugent, 'Western architecture is making India's heatwaves worse', Time, 16 May 2022, https://time.com/6176998/india-heatwaves-western-architecture/. [5] Bhatia, 'Without architecture'. [6] Kavita Upadhyay, 'How heavy, unplanned construction and complex geology is sinking Joshimath', India Today, 16 January 2023, https://www.indiatoday.in/news-analysis/story/how-heavy-unplanned-construction-complex-geology-sinking-joshimath-uttarakhand-2319530-2023-01-10. [7] Satya Prakash, 'Supreme Court upholds Shimla Development Plan — 'Vision 2041', sets aside National Green Tribunal order', The Tribune, 11 January 2024, https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/himachal/supreme-court-upholds-shimla-development-plan-—-vision-2041-sets-aside-national-green-tribunal-order-580368. [8] Lokesh Ohri, 'Joshimath collapse: Uttarakhand is on the brink', The Indian Express, 9 January 2023, https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/joshimath-collapse-uttarakhand-brink-8370295/. [9] Alain De Botton, The Architecture of Happiness (London: Penguin, 2006), 267.

Holt’s paper, for example, evoked the relevance of mineral resources in the context of digitalisation, especially with regard to the humanities. Mineral resources make our daily life possible, though we take them for granted. Digitalisation, which is as indomitable as it is universal, also shapes our research practices and relies heavily on mineral resources. This text, for instance, was written on a laptop produced in Taiwan with mineral resources from China and Latin America, and I also use it to read digital papers by scholars from the Netherlands, the USA and India.

The more we digitalise, the more we lose a genuine connection to our analogue environment. But ironically, that same digitalisation and environmental alienation coincides with greater environmental exploitation. Materials are a medium by which we surpass our natural boundaries and enter a digital space. We do well to remember, however, that this journey is predicated on natural resources. The virtuality of digitalization is an illusion. In the end, everything is analogue.

Many of the presentations, especially those from Boddy, Grüner, Mishra and Moore highlighted the importance of reflecting on emotions in research. Art is emotion; it is, to paraphrase Benjamin Myers, the desire to cast the moment in amber.

Holt’s paper, for example, evoked the relevance of mineral resources in the context of digitalisation, especially with regard to the humanities. Mineral resources make our daily life possible, though we take them for granted. Digitalisation, which is as indomitable as it is universal, also shapes our research practices and relies heavily on mineral resources. This text, for instance, was written on a laptop produced in Taiwan with mineral resources from China and Latin America, and I also use it to read digital papers by scholars from the Netherlands, the USA and India.

The more we digitalise, the more we lose a genuine connection to our analogue environment. But ironically, that same digitalisation and environmental alienation coincides with greater environmental exploitation. Materials are a medium by which we surpass our natural boundaries and enter a digital space. We do well to remember, however, that this journey is predicated on natural resources. The virtuality of digitalization is an illusion. In the end, everything is analogue.

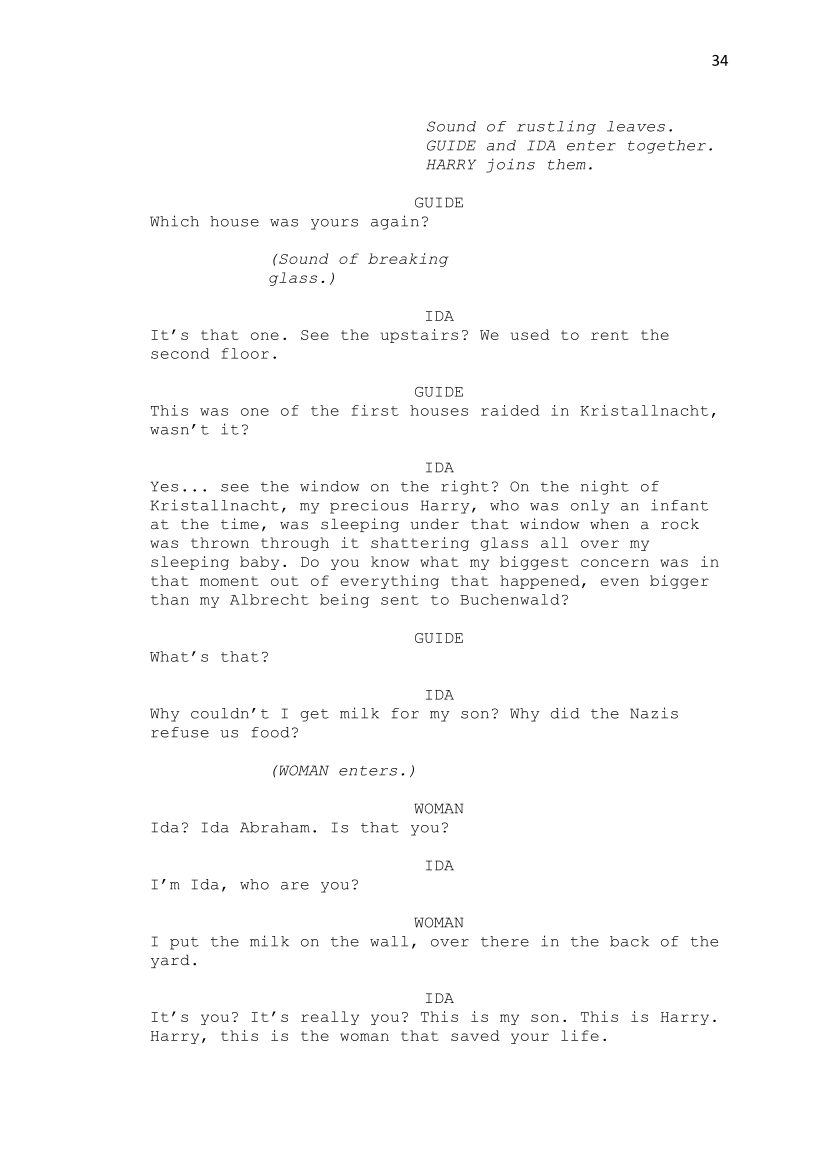

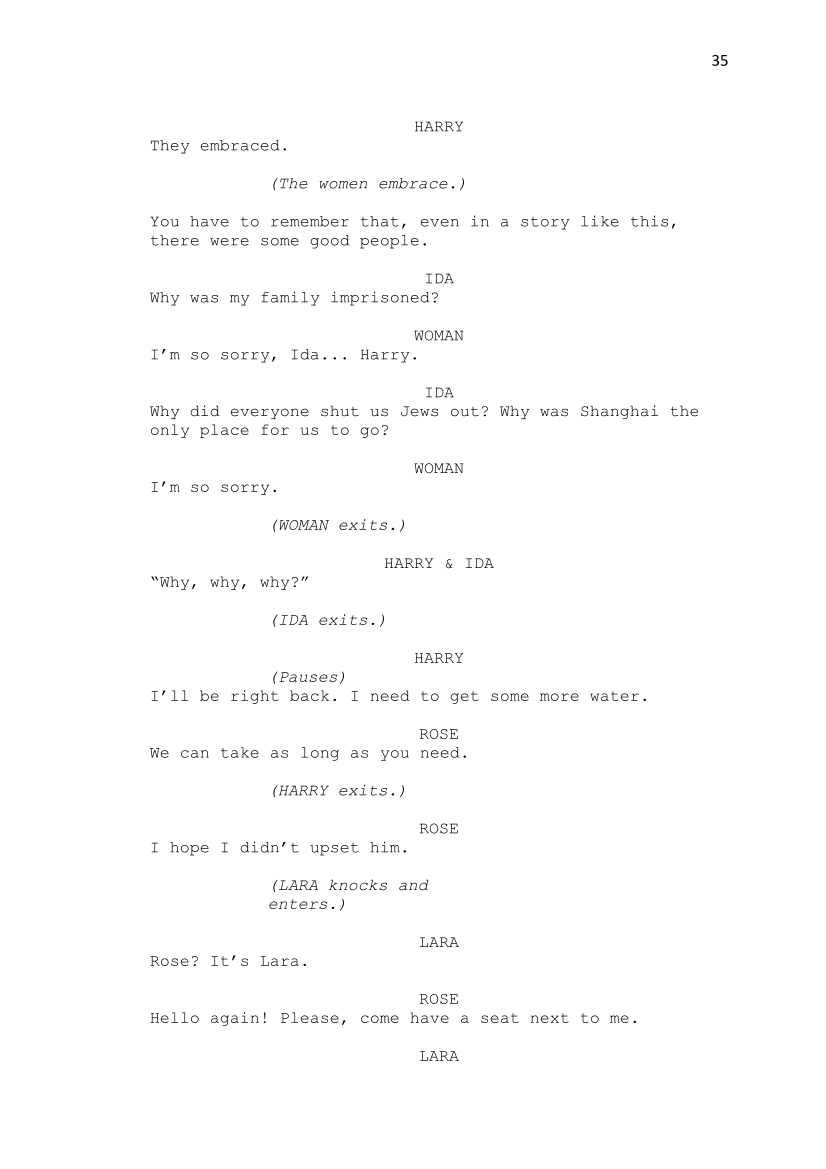

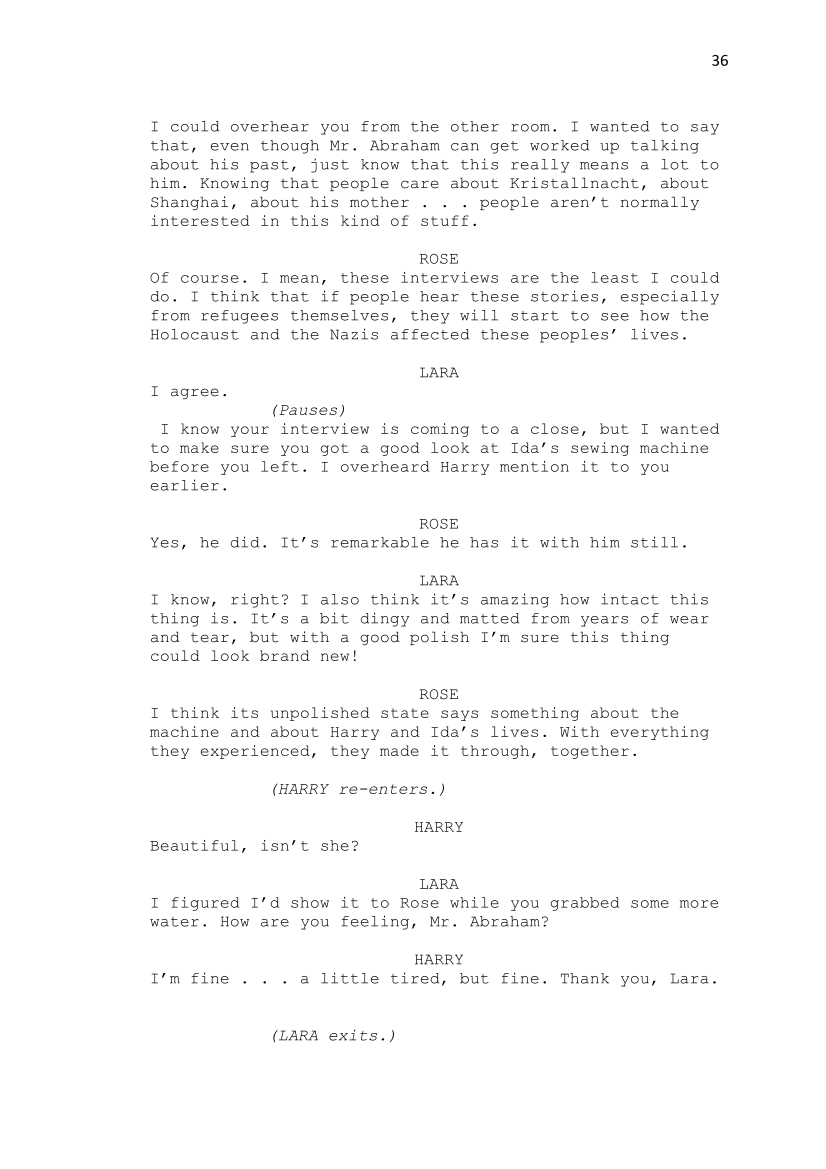

Many of the presentations, especially those from Boddy, Grüner, Mishra and Moore highlighted the importance of reflecting on emotions in research. Art is emotion; it is, to paraphrase Benjamin Myers, the desire to cast the moment in amber.