The Singer of Shanghai – a play about the Jewish diaspora (with introduction)

[Scroll down for the complete script and an audio recording of the play as performed by the playwrights.]

Introducing The Singer of Shanghai

kari-anne innes & kevin ostoyich

What is historical theatre?

At its heart, historical theatre allows students to create and perform works that convey historical meaning to an audience. The goal is to break the traditional boundaries of the teacher-student echo chamber and encourage students to communicate with the past and educate the public of the present and future directly. Historical theatre encourages students to employ empathy, artistry and intellect to connect with and convey the humanity of the past. Historical theatre helps students to see history not merely as an academic exercise, but a living relationship between past and present. Historical theatre is not a genre, but a pedagogy that merges two disciplines to create a distinct product — whether it be a script or the performance thereof — that can be experienced and/or performed by others in an ongoing conversation of educational discovery and human understanding.

The genesis of The Singer of Shanghai

The Singer of Shanghai is the third play to result from our historical theatre programme. The previous plays, Knocking on the Doors of History: The Shanghai Jews (2016) and Shanghai Carousel: What Tomorrow Will Be (2019), were both written and performed at Valparaiso University.[1] The Singer of Shanghai arose from a series of interviews Kevin Ostoyich conducted with Harry J. Abraham as well as field research Ostoyich conducted in Frickhofen and Altenkirchen, Germany.[2] Ostoyich supplied students with the interviews with Abraham as well as those of other former Shanghai refugees. The group also read various articles that Ostoyich had written about Shanghai Jewish refugees, most importantly his article about Harry J. Abraham, ‘From Kristallnacht and Back: Searching for Meaning in the History of the Shanghai Jews‘ and his article that incorporates Ida Abraham’s experiences, ‘Mothers: Remembering Three Women on the 80th Anniversary of Kristallnacht’.[3] Ostoyich challenged the students to use the oral testimony and other materials to write a play about a sewing machine that accompanied the Abraham family on their long journey from Germany to China and ultimately to the USA. The format, structure and themes of the play were to be determined collectively by the students and professors. Each member of the group was to contribute research and writing to a script that would narrate the history of the Abraham family and convey the meaning of the sewing machine.

A note on historical accuracy

The Singer of Shanghai closely follows the history of the Abraham family and much of the ‘interview’ dialogue in the play comes directly from conversations with Harry. Nevertheless, there are several places in the script where the playwrights incorporated elements from other oral testimonies of former Shanghai Jewish refugees (all of which based on Ostoyich’s interviews). Therefore, the play is best considered a historical composite. The use of old parachute fabric in making clothes in Shanghai comes from the testimony of Inga Berkey — a former Shanghai Jewish refugee who is also a friend of Harry’s. The description of children playing with marbles and cigarette packs comes from the testimonies of Helga Silberberg and Gary Sternberg. The playwrights drew inspiration from the interaction of refugee children with American GIs immediately after the Second World War from several oral testimonies (including Harry’s). They drew most heavily from the testimony of Bert Reiner for this scene. It was thus appropriate that Bert Reiner played the American GI in the radio-theatre version of the play. The lyrics of the song You Look Just Like a GI, My Friend, which is sung in the background and inspired dialogue, originate from the Shanghai Jewish refugee community. Ostoyich found the German lyrics in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, translated them and provided his translation along with translated songs from Shanghai for use in the play. The group incorporated the song into the play because the lyrics echo the common refrain in the oral testimonies about how much the refugees (especially the children) were fascinated by the sudden influx of so many American GIs into the city.

Whereas the interviews with Harry provided text for much of the play’s interview dialogue, the playwrights wrote original dialogue for the flashback sequences. Such instances allowed them to work creatively within the boundaries of the historical space. In such instances, students explored the connection between themselves and the history to write dialogue appropriate to the historical context and that expresses their own observations and reflections.

This framework of performing stories of the other to inspire dialogue between the subject (the actor) and the object of study (individual stories of humanity) is inspired by the performance theories of Dwight Conquergood. Conquergood drafted a ‘moral map’ to guide performers toward a balance of committing to the embodiment of the other while remaining detached enough to respect that it is not their story.[4] Thus, students identify with the subject’s circumstances, words and feelings while acknowledging differences, therefore enabling them to approach history empathetically yet objectively. Each student’s understanding and experience of history becomes as personalised as the stories themselves. The student’s experience of history is affected – moved in mind and feeling. In turn, through performance, the student affects the audience, deepening the shared experience of history, an experience that is at once based on historical accuracy yet particularised to each individual’s understanding and reflections.

A brief introduction to the history of the Shanghai Jews

Facing increasing discrimination from the Nazis, many Jews started to look for a refuge. In the wake of the pogrom that swept through Germany and Austria on the night of 9/10 November 1938 (known as the Reichsprogramnacht, Kristallnacht, or ‘Night of Broken Glass’), many Jews (such as Albrecht Abraham in Altenkirchen and Sigfrid Rosenthal in Frickhofen) were rounded up and sent to concentration camps. Often, it then fell to women (such as Ida Abraham) to try to extract their husbands, fathers, brothers and/or sons from the camps and lead their families to safety. Immediately after Kristallnacht, it was still possible to secure release if assurances of emigration were given immediately. Nevertheless, the Jews found that doors to the West were often closed due to a combination of quota policies, bureaucratic obstacles and outright anti-Semitism. One peculiar destination became attractive because no entry visa was required: Shanghai, China.

The British pried Shanghai open to the West following the Opium Wars in the 19th century. The city was split into different sections administered by Western colonial powers. The International Settlement was governed by the Shanghai Municipal Council (predominantly under British and American control), and the French Concession was under French control. During the 1930s, the Japanese invaded China. In 1937, the Japanese established control in north-eastern Shanghai. Thus, as Jewish refugees fled to Shanghai, they entered a city that was partitioned into various sections subject to varied administrative regimes.

In December 1941, concurrent to attacking Pearl Harbor, the Japanese forcibly subjugated the International Settlement and started to intern British and American citizens as enemy combatants. This left European refugees vulnerable. Many of the Sephardic Jews who had roots in the city since the 19th century and who had helped the refugees with housing, kitchens and so on could no longer assist them because the Sephardic Jews, themselves, either fled the city or were forced into internment camps due to their being British citizenship.

In February 1943, the Japanese occupiers proclaimed that all stateless persons who had entered the city after 1 January 1937 had to move into a ‘Designated Area’ in the depressed Hongkew district by 18 May 1943. Approximately half of the 16,000 to 20,000 refugees already lived in the Designated Area; others had to move (losing many possessions in the process). The Designated Area has often been called the ‘Shanghai Ghetto’. This should not be confused with the ghettos of Europe during the Holocaust (such as those in Warsaw, Łódź, etc). Though allied to the Germans during the Second World War, it was not Japanese policy to kill Jews. This did not, however, mean the Designated Area was pleasant. Refugees tend to remember the time in the Designated Area until the end of the war as a time of hunger, poverty and disease. Their movement was severely restricted, and they needed to apply for passes to leave the Designated Area. The application process was often humiliating, and passes were never assured. Shortly after the Americans dropped atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, the Japanese left Shanghai. As the Japanese left, American soldiers entered, met with jubilation and relief on the part of the refugees. Nevertheless, such euphoria was soon tempered by the tragic news of what had happened to the Jews in Europe during the war. Lists of those murdered in what would become known as the Holocaust or Shoah started to be posted in Shanghai. The refugees then started to realise how important Shanghai had been in shielding them from the fate of friends and relatives who succumbed to the Nazis.

The history of the Shanghai refugees was long barely known. The refugees went on with their lives, and most chose not to speak of their past. In his interviews, Ostoyich has often heard that no one seemed very interested in their story. Recently, scholars and documentary filmmakers have discovered the history of the Shanghai refugees. They have found that, despite tremendous obstacles, the refugees were able to build a surprisingly vibrant community with art, theatre cabaret, music, cinemas, schools, etc in their ‘harbor from the Holocaust.’[5] We hope this play not only helps to introduce the history of the Shanghai refugees to a wider public, but also honours the artistic expression of those refugees. Most importantly, the playwrights have taken their cue from Harry J. Abraham in centring the story on the pogrom of 9/10 November 1938. The importance of Shanghai can only be understood in the context of the pogrom and the collective silence and inaction of people and countries to respond to the discrimination and violence that was being unleashed on the Jews.

[1] For more a more detailed description of historical theatre, see Kari-Anne Innes, Kevin Ostoyich, and Rebecca Ostoyich, ‘Turning “Limitations” into Opportunities: Online and Unbound’, in Undergraduate Research in Online, Virtual, and Hybrid Courses: Proactive Practices for Distant Students, ed. Jennifer G. Coleman, Nancy H. Hensel, and Campbell, William E. (New York: Stylus Publishing, 2022); Kari-Anne Innes and Kevin Ostoyich, ‘Characterizing Interdisciplinarity in Historical Theatre: Exploring Character with the History Student’, Theatre/Practice: The Online Journal of the Practice/Production Symposium of the Mid America Theatre Conference 10 (2021). (Published online, 8 April 2021: http://www.theatrepractice.us/current.html).

[2] Ostoyich learned a great deal from Hubert Hecker in Frickhofen and Werner Ziedler in Altenkirchen.

[3] Kevin Ostoyich, ‘From Kristallnacht and Back: Searching for Meaning in the History of the Shanghai Jews’ (History Faculty Publication, Valparaiso, 2017); Kevin Ostoyich, ‘Mothers: Remembering Three Women on the 80th Anniversary of Kristallnacht’, American Institute for Contemporary German Studies of Johns Hopkins University, accessed 4 January 2023, https://www.aicgs.org/2018/11/mothers-remembering-three-women-on-the-80th-anniversary-of-kristallnacht/.

[4] Dwight Conquergood, ‘Performing as a Moral Act: Ethical Dimensions of the Ethnography of Performance’, in Cultural Struggles: Performance, Ethnography, Praxis, ed. Patrick E. Johnson (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013), 65–80.

[5] Tang Yating, ‘Reconstructing the Vanished Musical Life of the Shanghai Diaspora: A Report’, Ethnomusicology Forum 13, no. 1 (2004): 101–18, https://doi.org/10.1080/1741191042000215291. We draw here from the PBS documentary titled Harbor from the Holocaust, Director: Violet Du Fang, Writer: Lynne Squilla, 2020.

bibliography

Conquergood, Dwight. ‘Performing as a Moral Act: Ethical Dimensions of the Ethnography of Performance’. In Cultural Struggles: Performance, Ethnography, Praxis, edited by Patrick E. Johnson, 65–80. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013.

Innes, Kari-Anne, and Kevin Ostoyich. ‘Characterizing Interdisciplinarity in Historical Theatre: Exploring Character with the History Student’. Theatre/Practice: The Online Journal of the Practice/Production Symposium of the Mid America Theatre Conference 10 (2021).

Innes, Kari-Anne, Kevin Ostoyich, and Rebecca Ostoyich. ‘Turning ‘Limitations’ into Opportunities: Online and Unbound’. In Undergraduate Research in Online, Virtual, and Hybrid Courses: Proactive Practices for Distant Students, edited by Jennifer G. Coleman, Nancy H. Hensel, and Campbell, William E. New York: Stylus Publishing, 2022.

Ostoyich, Kevin. ‘From Kristallnacht and Back: Searching for Meaning in the History of the Shanghai Jews’. History Faculty Publication. Valparaiso, 2017.

———. ‘Mothers: Remembering Three Women on the 80th Anniversary of Kristallnacht’. American Institute for Contempoary German Studies of Johns Hopkins University. Accessed 4 January 2023. https://www.aicgs.org/2018/11/mothers-remembering-three-women-on-the-80th-anniversary-of-kristallnacht/.

Yating, Tang. ‘Reconstructing the Vanished Musical Life of the Shanghai Diaspora: A Report’. Ethnomusicology Forum 13, no. 1 (2004): 101–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1741191042000215291.

The Singer of Shanghai, as performed by the playwrights

The Singer of Shanghai (complete script)

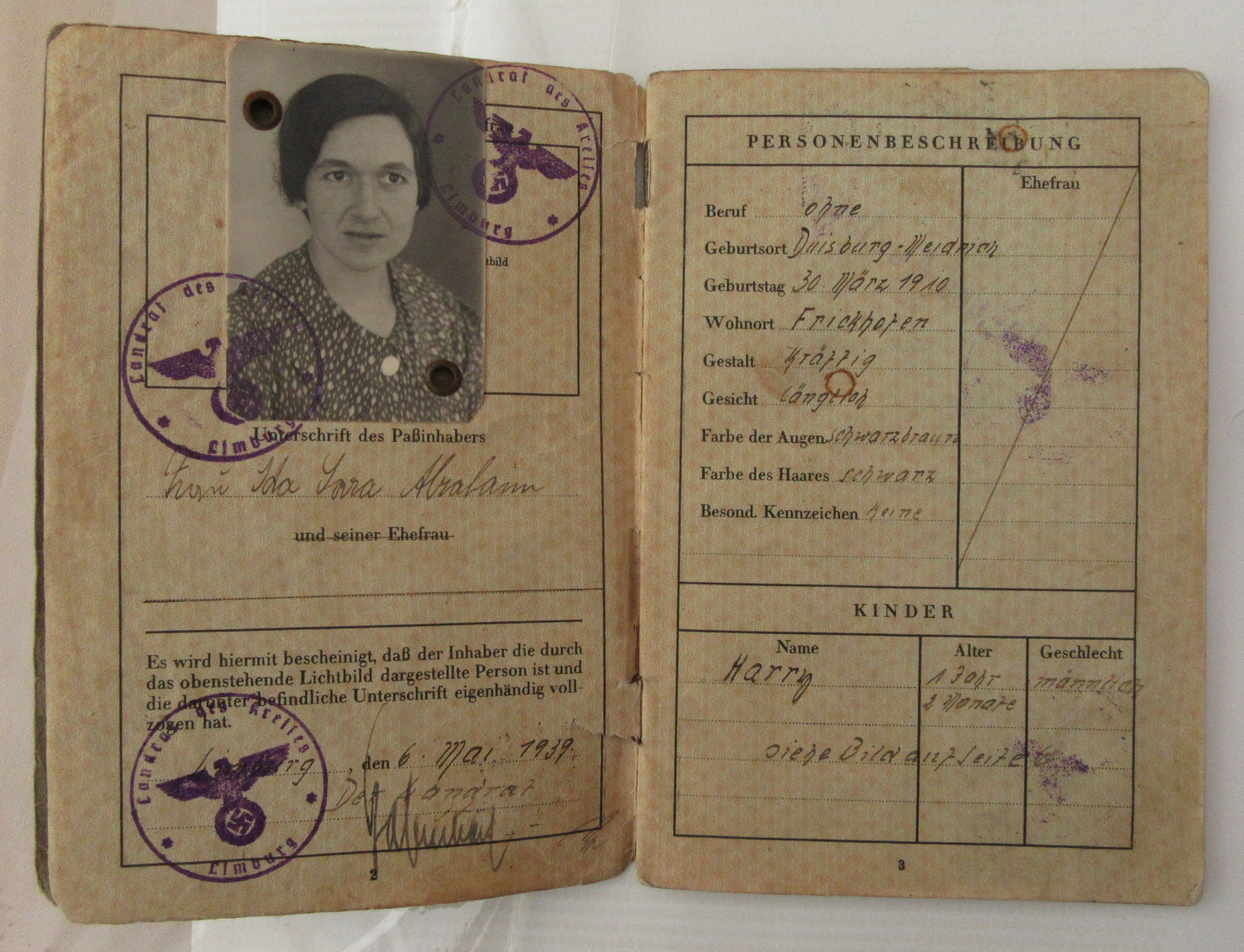

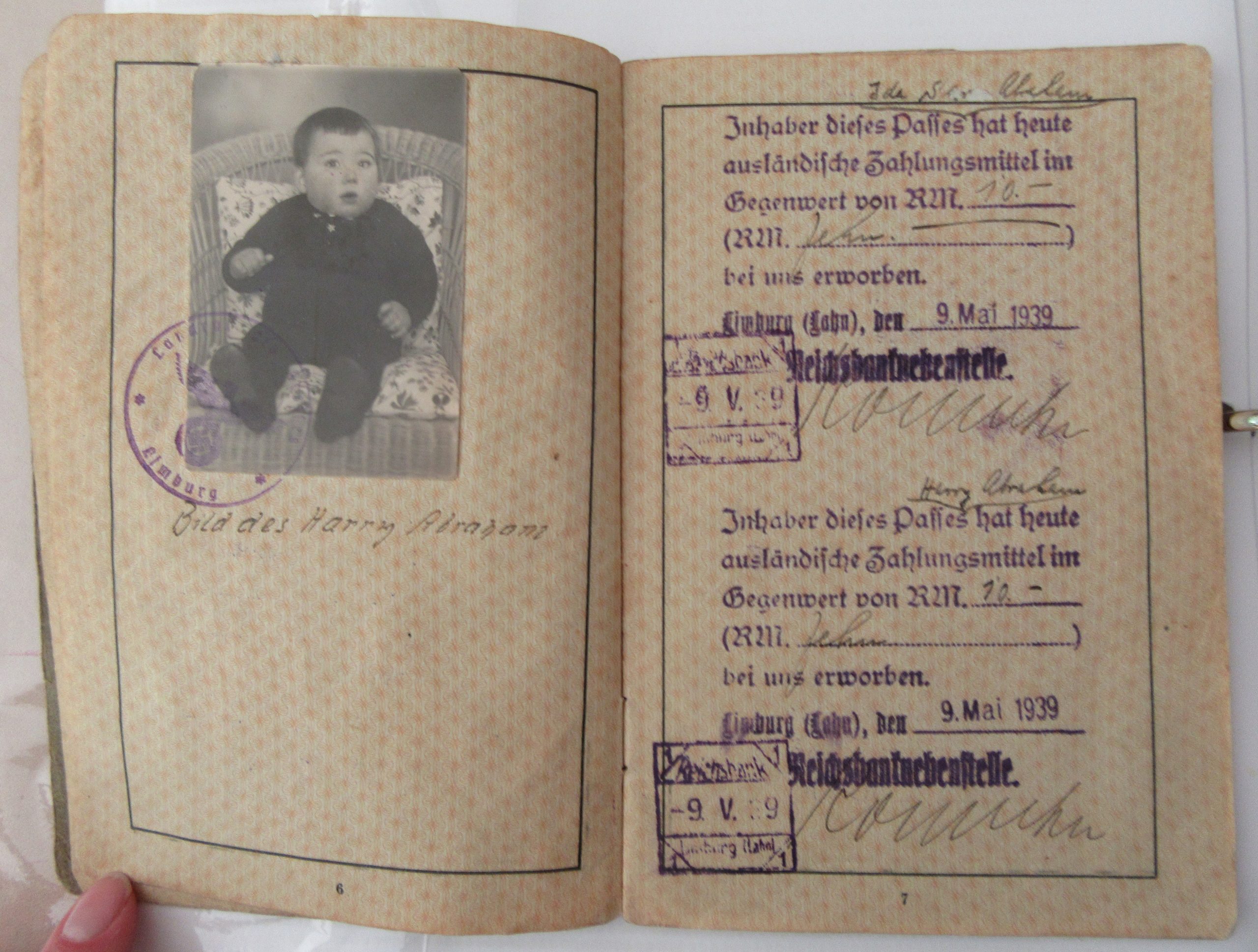

Ida Abraham’s Nazi-issued passport from 1939 (Photo by Rebecca Ostoyich and courtesy of Harry J. Abraham and family)

Harry J. Abraham’s Nazi-issued passport from 1939 (Photo by Rebecca Ostoyich and courtesy of Harry J. Abraham and family)

Harry J. Abraham posing beside his mother’s sewing machine ca. 2017 (Photo courtesy Harry J. Abraham and family)

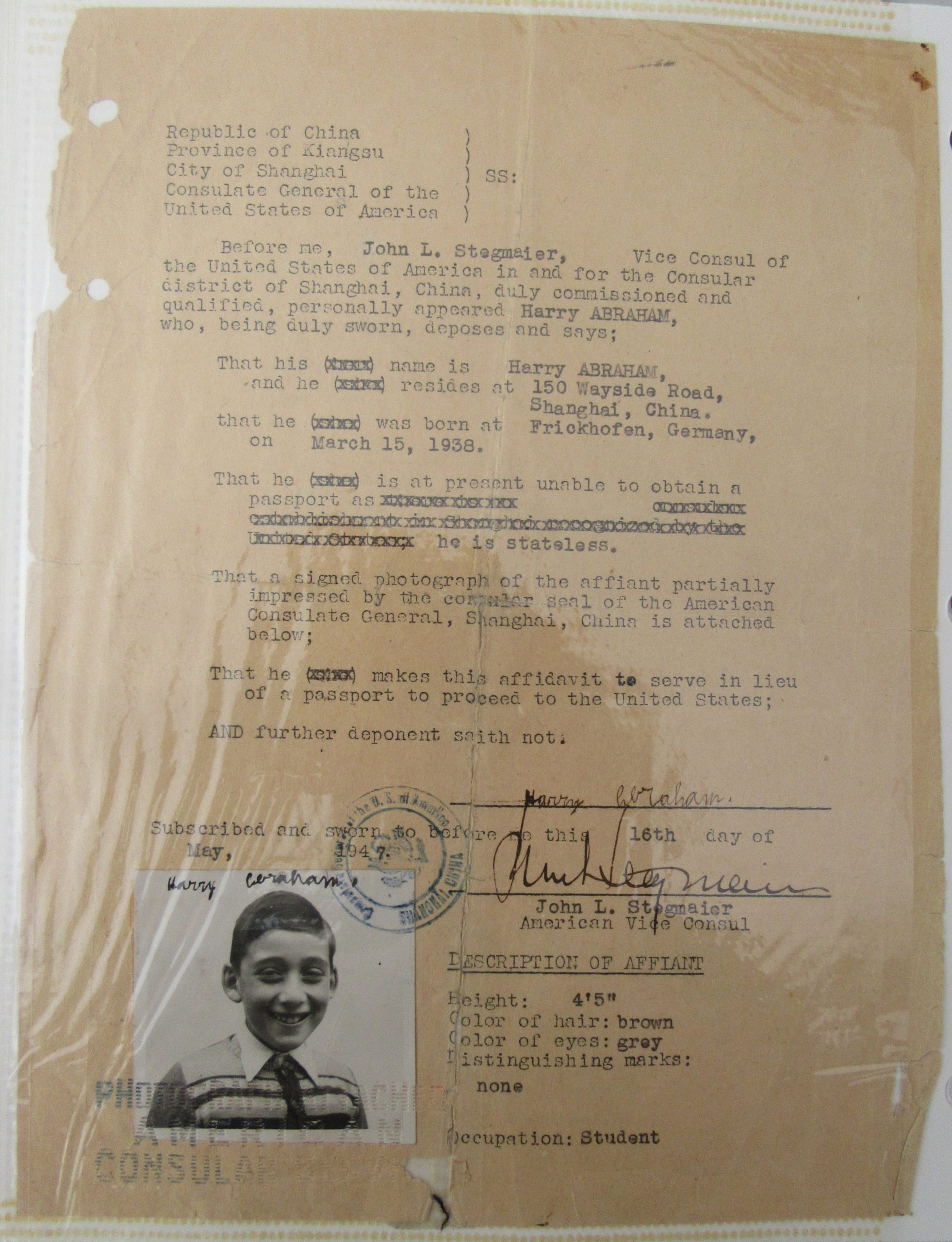

Harry J. Abraham’s identification issued by the US consulate in Shanghai in 1947 for travel to the USA (Photo by Rebecca Ostoyich)

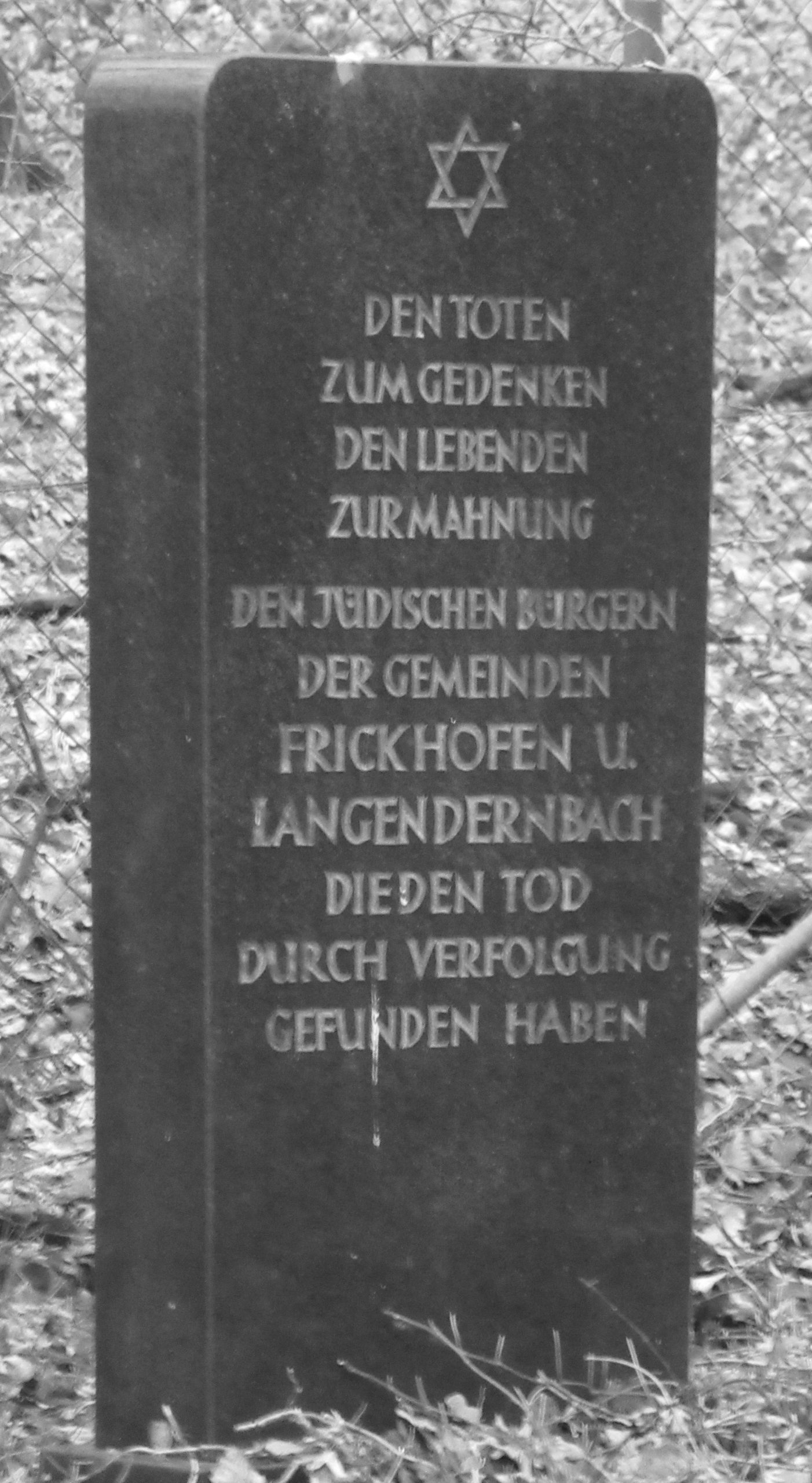

Figure 5: A memorial in the Frickhofen Jewish cemetery to the Jews murdered by the Nazis (Photo by Kevin Ostoyich)

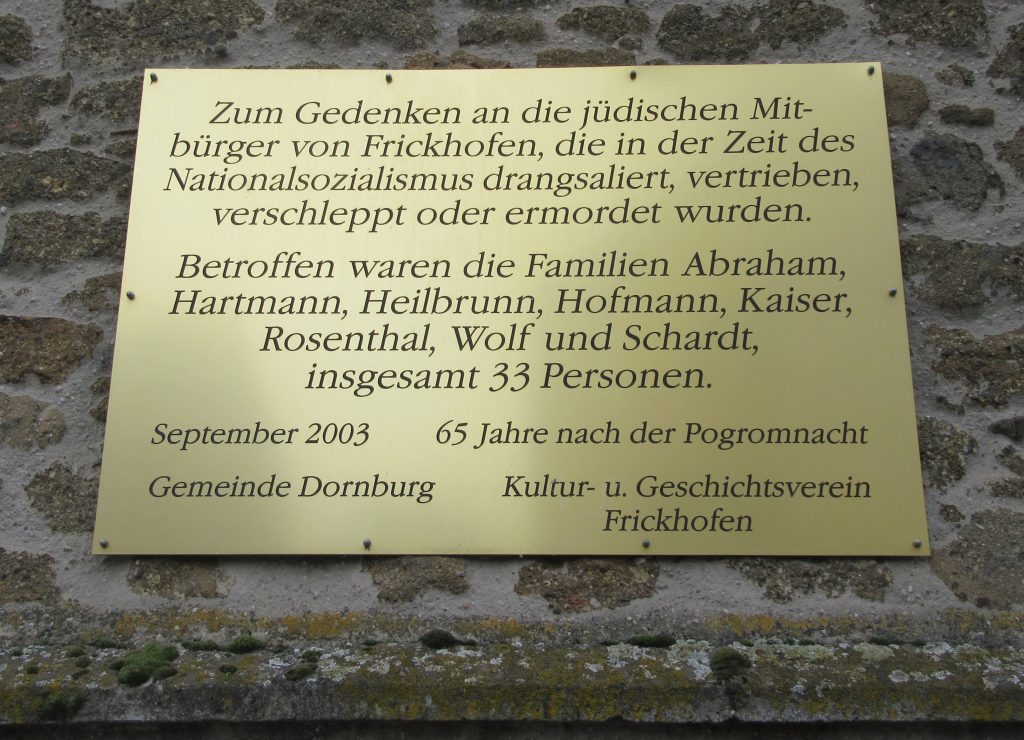

A plaque on the Frickhofen town hall memorialising the 33 murdered Jews of the town and their suffering at the hands of the Nazis (Photo by Kevin Ostoyich)

Harry J. Abraham with his parents Ida and Albrecht in Shanghai (Photo courtesy Harry J. Abraham and family)