In

Blog 2022

tom menger[1]

He saw in oil a weapon, and he heard groaning in the bowels of the Earth when the jack pumped up the oil (…)

From Varujan Vosganian’s novel Book of Whispers (2018 [2009])[2]

What if global dis:connectivity stretches not only around the surface of our globe, but also into its crust? Let me present some initial thoughts on this idea from the perspective of global oil and gas extraction since the nineteenth century.

Since August 2021, I have been researching early colonial oil extraction (ca. 1880-1920) at

global dis:connect. Specifically, I am investigating the imperial infrastructures

in situ that made such extraction possible and that bound commodities into global networks of extraction and consumption, creating new connections while simultaneously diverting or cutting others. In this piece, however, I want to chart a more experimental course and look, from a broader dis:connective as well as historical and contemporary angle, at oil and gas drilling as connecting and disconnecting the world above with its lithosphere − what one could tentatively call lithospheric connectivity. Obviously, this human foray into the earth did not only involve fossil fuels but all sorts of minerals. Here, however, I focus mainly on oil and gas extraction.

Humans have been digging into the earth for millennia – deep mines were already known in antiquity. In China, oil wells up to 240 metres deep already existed in 347 BCE. Nevertheless, fossil fuel extraction and the consequent incursions into the lithosphere grew dramatically from the second half of the nineteenth century onwards. This was ‘the golden age of resource-based development’, when the last yet-unincorporated territories were colonised and capitalist power pushed into these new, non-commodified spaces − a process Jason Moore has called the ‘lifeblood’ of capitalism.

[3]

The urge to dig deeper was certainly unprecedented, as for instance in the oil boom of the second half of the nineteenth century. While it is little known, many of the areas that were to become centres of Western colonial oil extraction actually already had local extraction infrastructures. Some were quite elaborate, others more rudimentary. In British-occupied Burma, at the Yenangyaung fields, Western oilmen came upon an extensive hand-dug well industry, controlled by a hereditary monopoly of 24 men and women, named the

twinzayo.

[4] In the Mesopotamian oilfields (i.e. Iraq), European travellers noted how fissures where oil seeped from the rocks were leased out by the state and that lease-holders had artificially deepened these natural wells with, for instance, steps hewn out in the rock. At some places, wage labourers emptied the oil pits every four or five days; at others the oil was channeled through iron tubes into collection reservoirs.

[5]

Generally, however, these wells did not reach very far into the lithosphere. In Burma, most wells were 46-76 metres deep; in Mesopotamia they were only a few metres deep.

[6] Depth was not really necessary; often the shallow wells were already producing enough to cover local demand. Transportation obstacles also made it unprofitable to produce for further afar.

Producing for further afar, however, was exactly what the incoming Europeans wanted. Their ceaseless extension of horizontal, global lines of transport was what drove the vertical push deeper into the earth. When a German military commando unit, the first Westerners to drill in Mesopotamia during wartime in 1917-1918, arrived on site, they already had with them steam-powered drilling equipment able to reach a depth of 400 metres.

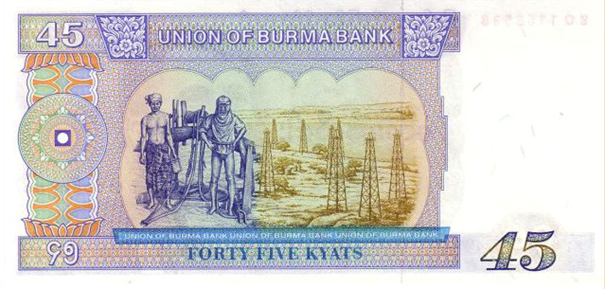

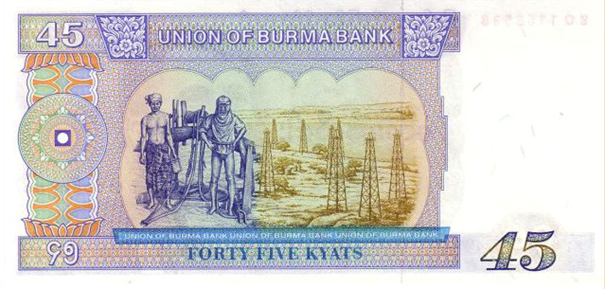

[7] In Burma too, the depth of the existing wells was quickly overtaken by new wells drilled by industrial machinery. Interestingly, however, the twinzayo reacted by adopting the diving dress, which allowed their drillers to stay underground for longer and deepen their wells, thus remaining competitive for several decades.

[8]

This Bank of Burma banknote, first issued in 1987, shows a Burmese oil driller carrying a diving dress (Image: Nsmm45, Wikipedia).

This Bank of Burma banknote, first issued in 1987, shows a Burmese oil driller carrying a diving dress (Image: Nsmm45, Wikipedia).

But how connected was humankind really with the subsoil? Relative to the enormity of the lithosphere, these wells remained limited in depth as well as extraction. The Germans in Mesopotamia, could not operate the machinery for their deep drills, first by a lack of personnel, then by the collapse of the front, which saw the German connection to the area cut (the region was taken over by the British Empire, whose engineers would only resume drilling there in 1927).

[9]

Furthermore, drillers actually extracted very little of Original Oil In Place (OOIP), a technical term denoting the total amount of oil present in a basin. For a long time, drillers had only the vaguest estimates of how much of this OOIP they actually extracted, although they sensed that it was very little. In 1925, some 65 years after first industrial oil extraction in Pennsylvania, a German study surveyed the existing literature and concluded the rate of extraction could be anywhere between 4 and 20 per cent. Later research has shown this to be closer to 5-15 per cent (obviously, the exact amounts vary depending on the location). A French expert was cited who, with some justification, held that an oil well, for all the industrial machinery and the drilling towers, was nothing but a ‘pin prick’ into the earth.

[10]

For most of this extraction, the drillers relied not on machinery but on the forces of nature. Natural water or gas, reacting to pressure differences in underground basins, is generally what pushed the oil to the surface. Initially, this often occurred with great force, as we know from the famous images of blowouts or ‘geysers’.

An oil gusher in the Kirkuk district, Iraq, c. 1932 (Image: G. Eric and Edith Matson, Matson Photographic Collection, Library of Congress, Wikimedia)

An oil gusher in the Kirkuk district, Iraq, c. 1932 (Image: G. Eric and Edith Matson, Matson Photographic Collection, Library of Congress, Wikimedia)

Interestingly, too much connectivity was actually a bad thing here. The more ‘pin pricks’ into the Earth, the more outlets to release pressure that would otherwise push the oil to the surface. However, as the article quoted above noted, human egotism generally led to an ‘overdose’ of such connectivity, as there were too many rival actors at the same spot (at least initially).

[11] As we now know, perforating the Earth in that way was also detrimental in that it released the natural gas (mostly methane) from the reservoir into the atmosphere. Such gas leakage remains an important contributor to climate change.

Over the course of the twentieth century, new drilling technology enabled the oil industry to penetrate ever deeper. In 1949, when records began, the average depth of oil wells was already 3635 feet (1108 metres). By the end of the 2010s, it sank to nearly 6000 feet (1828 metres, or 1,8 kilometres). Outliers are poorly reflected in these averages. The world’s deepest well (measured by true vertical depth) in the Tiber Oil Field, in the American portion of the Gulf of Mexico, pierces 10.87 kilometres into the ground (though it is currently dormant). Worldwide, ‘shallow’ oil reserves are largely exhausted. The introduction of directional drilling in the 1970s has changed the idea of depth itself, as it entails drilling horizontally from a certain depth. The former ‘pin pricks’ thus become tentacles, extending our subterranean reach. Depth is no longer equivalent to distance. For example, the Sakhalin O-14 well in Russia, with a modest depth of a less than a kilometre belies an astonishing length of nearly fifteen kilometres.

[12]

It should also be noted that the hunger for fossil fuels did not drive human infiltration into the lithosphere alone. Superpower rivalry was another motive. In 1970, the Soviet Union started drilling the Kola Superdeep Borehole (on the Kola Peninsula, near the Norwegian border), to reach the deepest artificial point on Earth. This was not ventured as a hunt for fuel, but as a scientific feat. In 1979, it became the deepest borehole in the world, surpassing the Bertha Rogers oil well in the United States. Despite several breakdowns and interruptions, the Soviets reached a depth of 12,262 metres in 1989. Symbolising the breakdown of the Soviet Union itself, the borehole could go no deeper, though drilling from other holes at the same shaft continued into the early 1990s till financial problems prompted its abandonment in 1994. The temperatures at that depth exceeded expectations, and the rock became plastic, precluding further drilling.

[13]

Technology has not only changed the depth of humanity’s reach into the Earth, but also its intensity. Primary recovery — the initial phase of production — can extract some 5-15 per cent of OOIP. When the pressure starts to fall, as is natural in all producing oil reservoirs over time, yields decrease. Pumps can compensate for a while, but that is where primary recovery ends. Therefore, the oil industry has long been using secondary recovery: flooding water or gas into the reservoirs, thus restoring pressure. This allows for more extraction, though typically only to some 30-50 per cent.

Recent decades have seen the adoption of tertiary recovery, which can increase yields by an additional 5-15 per cent. These processes, which mostly involve the injection of further fluids into the reservoirs, impact the subsoil drastically. For heavy oil, these processes are mostly thermal, reducing viscosity through heat to ease extraction. This can involve introducing hot steam into the Earth under heavy pressure or simply burning part of the oil underground to release part of the rest. Other methods include injecting chemicals into the wells or using microbes (though the latter, apparently less damaging, is still very rare).

[14]

Human efforts to extract the resources of the lithosphere reach their maximum when just over half of the OOIP has reached the surface. The natural properties of subterranean oil resist some of the oil industry’s machinery, which leads some scientists to speak anthropomorphically of ‘recalcitrant oil fields’.

[15]

Moreover, reaching into the Earth also has unintended consequences. As Martin Meiske has noted for huge artificial canals, humankind cannot interfere with impunity in what took geological processes millions of years to create.

[16] While the damage done by oil extraction above ground is well-known (e.g. pollution and human conflict), the effects underground can be at least as intense. For instance, in the Dutch province of Groningen, where natural gas has been extracted from below ground for decades, empty gas reservoirs have destabilised the soil, leading to increased seismic activity, with homes sinking and fracturing.

[17] Hydraulic fracturing (‘fracking’), another aggressive mode of extraction, whereby rock formations containing gas or oil are ‘cracked open’ by injecting liquids at high-pressure, has led to the contamination of groundwater and triggered earthquakes in fracking areas in the United States and elsewhere.

However, will the anticipated ‘end of oil’, or fossil fuels more generally, disconnect us from the lithosphere at some point? Despite the currently breath-taking rise in fuel prices, pressure to decarbonise will eventually make reaching deep into the lithosphere for oil and gas unprofitable. In the long run, all such connections will be cut.

[18] Will this mean a retreat of lithospheric connectivity?

First, abandoning and plugging oil wells have been a constant in the age of fossil fuels. Wells that fail to produce are abandoned. This points to a key aspect of dis:connectivity: connection and disconnection generally occur simultaneously, and they are mutually constitutive. On Sumatra, another of my case studies involving early oil extraction in a colonial setting, the Peureulak oil field in Aceh, was the field that effectively launched the Royal Dutch Shell oil company. However, by the time Shell had become one of the world’s main oil companies, the Peureulak field was already exhausted and abandoned, leaving a huge area of derelict pumps, tubes and polluted soil (though drilling continued in other parts of the island).

[19]

Currently, some 29 million wells have been abandoned globally, which brings us to the second point: abandoning a well does not disconnect it from our surface and atmosphere. Instead, many continue to leak gas or oil, sometimes for more than a century (and some might go on for another century). By one estimate, 2.5 million tonnes of methane might escape abandoned wells globally per year, with the annual damage to our climate equivalent to three weeks of current US oil consumption.

[20]

Third, rather than cut connections, we will likely merely reverse their direction. While we have mostly been extracting hydrocarbons from the Earth, there are ambitious plans to refill oil and gas reservoirs with carbon dioxide sequestered from the atmosphere. Ironically, however, this is in part intended as a way to access the oil remaining in ‘depleted’ oilfields. As it is, injecting carbon dioxide into these reservoirs can modify some qualities of the oil still in place so that it is more easily released from the rock. This ‘CO

2-Enhanced Oil Recovery’ is represented as a bridge to a carbon-free future — still extracting oil for consumption while simultaneously sequestering carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. According to one study CO

2-EOR has the potential to sequester 140 billion tonnes of CO

2 (for comparison: global annual emissions are now some 36 billion tonnes). In the Permian Basin in the United States and elsewhere, there is already an extensive pipeline network carrying carbon dioxide to oilfields.

[21]

If subsoil sequestration of carbon dioxide does indeed take off globally, we might soon have a global network of such pipelines. One day, however, even the underground reservoirs will be full, and this network might fall idle like the preceding infrastructures of lithospheric connectivity, becoming terminals to nowhere, testimonies to the human urge to penetrate and capitalise on the ground beneath our feet.

Let us return, finally, to the Kola Superdeep Borehole. According to a picture on Wikipedia, the borehole appears to have been welded shut sometime after the project was halted.

The Kola Superdeep Borehole, welded shut, August 2012 (Image: Rakot13, Wikimedia)

The Kola Superdeep Borehole, welded shut, August 2012 (Image: Rakot13, Wikimedia)

While closed now, its ability to ignite popular fantasies is unbroken. In 2020, it starred in a Russian horror film, in which a mysterious mould contaminates researchers in a fictitious secret lab deep down the shaft, causing them to melt into one huge aggressive creature that hunts for the rescuers on their way down.

[22] The real horror of lithospheric connectivity, however, might lay instead in its prolonged effects on our environment. The human ‘pin pricks’ into the Earth will prove of great consequence for all of us — and certainly also a subject worth exploring further from the perspective of a global lithospheric dis:connect.

[1] I thank Ben Kamis not only for his copy-editing but especially also for giving me the thematic suggestion for this piece.

[2] Unless otherwise indicated, all translations are my own.

[3] Jason W. Moore,

Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital (London: Verso, 2015), 82; Edward B. Barbier,

Scarcity and Frontiers: How Economies Have Developed Through Natural Resource Exploitation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), chap. 7, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511781131.008.

[4] Marilyn Longmuir, ‘Twinzayo and Twinza: Burmese “oil Barons” and the British Administration’,

Asian Studies Review 22, no. 3 (1998): 339–56.

[5] See for instance: Walther Schweer,

Die türkisch-persischen Erdölvorkommen (Hamburg: Friederichsen, 1919), 41–42.

[6] Longmuir, ‘Twinzayo and Twinza’, 341; Schweer,

Die türkisch-persischen Erdölvorkommen, 40–46.

[7] Erich Reuss, Reisebericht über die Kommandierung zum Brennstoffkommando in Arabien von Jan. 1917-März 1919, Landesarchiv Nordrhein-Westfalen, Oberbergamt Bonn BR 0101, Nr. 1286, pp. 5-6, 14.

[8] Marilyn V. Longmuir,

Oil in Burma: The Extraction of ‘Earth-Oil’ to 1914 (Bangkok: White Lotus Press, 2001), 158–59.

[9] Reuss, Reisebericht, p. 31; Ferdinand Friedensburg,

Das Erdöl im Weltkrieg (Stuttgart: Enke, 1939), 48–49.

[10] Gottfried Schneiders, ‘Wieviel Erdöl ist in verlassenen Ölfeldern zurückgeblieben?’,

Petroleum XXI, no. 13 (n.d.): 866.

[11] Schneiders, 866; E. Tzimas et al.,

Enhanced Oil Recovery Using Carbon Dioxide in the European Energy System (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the EU, 2005), 22.

[12] ‘Average Depth of Crude Oil and Natural Gas Wells’, U.S. Energy Information Administration, 1 October 2020, https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/pet_crd_welldep_s1_a.htm; ‘Longest Vertically and Directionally Drilled Oil and Natural Gas Wells Worldwide as of 2019’, Statista, November 2019, https://www.statista.com/statistics/479685/global-oil-wells-by-depth/; ‘How Far Do We Drill To Find Oil?’, Petro Online, 5 November 2014, https://www.petro-online.com/news/fuel-for-thought/13/breaking-news/how-far-do-we-drill-to-find-oil/32357.

[13] Christopher McFadden, ‘The Kola Superdeep Borehole Is the Deepest Vertical Borehole in the World’, Interesting Engineering, 29 March 2019, https://interestingengineering.com/the-real-journey-to-the-center-of-the-earth-the-kola-superdeep-borehole.

[14] Tzimas et al.,

Enhanced Oil Recovery, 21–22; Ann Muggeridge et al., ‘Recovery Rates, Enhanced Oil Recovery and Technological Limits’,

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 372, no. 2006 (13 January 2014): 20120320, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2012.0320. Also note that the sequence of primary to tertiary recovery has become increasingly obsolete, with tertiary techniques currently being used right from the beginning in a process now known simply as Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR).

[15] Christina Nikolova and Tony Gutierrez, ‘Use of Microorganisms in the Recovery of Oil from Recalcitrant Oil Reservoirs: Current State of Knowledge, Technological Advances and Future Perspectives’,

Frontiers in Microbiology 10 (2020): 1–18.

[16] Martin Meiske,

Die Geburt des Geoengineerings: Großbauprojekte in der Frühphase des Anthropozäns (Göttingen: Wallstein-Verlag, 2021), 205–7.

[17] Herman Damveld,

Gaswinning Groningen: een bewogen geschiedenis (Bedum: Profiel, 2020).

[18] ‘The Age of Fossil-Fuel Abundance Is Dead’,

The Economist, 4 October 2021, https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/the-age-of-fossil-fuel-abundance-is-dead/21805253.

[19]Anton Stolwijk,

Atjeh: het verhaal van de bloedigste strijd uit de Nederlandse koloniale geschiedenis (Amsterdam: Prometheus, 2016), 185-186.

[20] Nichola Groom, ‘Special Report: Millions of Abandoned Oil Wells Are Leaking Methane, a Climate Menace’, Reuters, 16 June 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-drilling-abandoned-specialreport-idUSKBN23N1NL.

[21] Michael Godec et al., ‘CO2 Storage in Depleted Oil Fields: The Worldwide Potential for Carbon Dioxide Enhanced Oil Recovery’,

Energy Procedia 4 (2011): 2162–69.

[22] Arseny Syuhin,

Superdeep [Kolskaya Sverhglubokaya], motion picture, 2020.

Bibliography

U.S. Energy Information Administration. ‘Average Depth of Crude Oil and Natural Gas Wells’, 1 October 2020. https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/pet_crd_welldep_s1_a.htm.

Barbier, Edward B.

Scarcity and Frontiers: How Economies Have Developed Through Natural Resource Exploitation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511781131.008.

Damveld, Herman.

Gaswinning Groningen: een bewogen geschiedenis. Bedum: Profiel, 2020.

Friedensburg, Ferdinand.

Das Erdöl im Weltkrieg. Stuttgart: Enke, 1939.

Godec, Michael, Neil Wildgust, Kuuskraa, Vello, Tyler Van Leeuwen, and Stephen L. Melzer. ‘CO2 Storage in Depleted Oil Fields: The Worldwide Potential for Carbon Dioxide Enhanced Oil Recovery’.

Energy Procedia 4 (2011): 2162–69.

Groom, Nichola. ‘Special Report: Millions of Abandoned Oil Wells Are Leaking Methane, a Climate Menace’. Reuters, 16 June 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-drilling-abandoned-specialreport-idUSKBN23N1NL.

Petro Online. ‘How Far Do We Drill To Find Oil?’, 5 November 2014. https://www.petro-online.com/news/fuel-for-thought/13/breaking-news/how-far-do-we-drill-to-find-oil/32357.

Statista. ‘Longest Vertically and Directionally Drilled Oil and Natural Gas Wells Worldwide as of 2019’, November 2019. https://www.statista.com/statistics/479685/global-oil-wells-by-depth/.

Longmuir, Marilyn. ‘Twinzayo and Twinza: Burmese “oil Barons” and the British Administration’.

Asian Studies Review 22, no. 3 (1998): 339–56.

Longmuir, Marilyn V.

Oil in Burma: The Extraction of ‘Earth-Oil’ to 1914. Bangkok: White Lotus Press, 2001.

McFadden, Christopher. ‘The Kola Superdeep Borehole Is the Deepest Vertical Borehole in the World’. Interesting Engineering, 29 March 2019. https://interestingengineering.com/the-real-journey-to-the-center-of-the-earth-the-kola-superdeep-borehole.

Meiske, Martin.

Die Geburt des Geoengineerings: Großbauprojekte in der Frühphase des Anthropozäns. Göttingen: Wallstein-Verlag, 2021.

Moore, Jason W.

Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital. London: Verso, 2015.

Muggeridge, Ann, Andrew Cockin, Kevin Webb, Harry Frampton, Ian Collins, Tim Moulds, and Peter Salino. ‘Recovery Rates, Enhanced Oil Recovery and Technological Limits’.

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 372, no. 2006 (13 January 2014): 20120320. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2012.0320.

Nikolova, Christina, and Tony Gutierrez. ‘Use of Microorganisms in the Recovery of Oil from Recalcitrant Oil Reservoirs: Current State of Knowledge, Technological Advances and Future Perspectives’.

Frontiers in Microbiology 10 (2020): 1–18.

Schneiders, Gottfried. ‘Wieviel Erdöl ist in verlassenen Ölfeldern zurückgeblieben?’

Petroleum XXI, no. 13 (n.d.): 865–70.

Schweer, Walther.

Die türkisch-persischen Erdölvorkommen. Hamburg: Friederichsen, 1919.

Syuhin, Arseny.

Superdeep [Kolskaya Sverhglubokaya]. Motion picture, 2020.

The Economist. ‘The Age of Fossil-Fuel Abundance Is Dead’, 4 October 2021. https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/the-age-of-fossil-fuel-abundance-is-dead/21805253.

Tzimas, E., A. Georgakaki, C. Garcia-Cortes, and S.D. Peteves,.

Enhanced Oil Recovery Using Carbon Dioxide in the European Energy System. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the EU, 2005.

citation information:

Continue Reading

Image: Dhammika Heenpella

Image: KHK global dis:connect collection

From left to right: Eiko Honda, Enis Maci, Anna Sophia Nübling (Image: Luzia Huber)

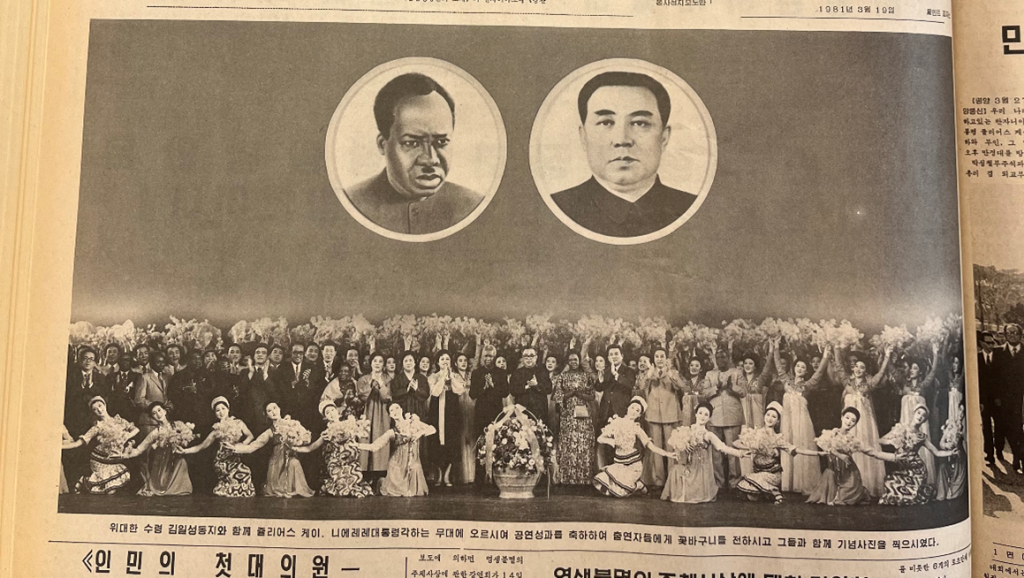

From left to right: Eiko Honda, Enis Maci, Anna Sophia Nübling (Image: Luzia Huber) Julius Nyerere and Kim Il Sung congratulating the actors and actresses after watching a musical <Song of Paradise> in Mansudae Art Theater (Rodong Shinmun March 28, 1981), photograph by the author.

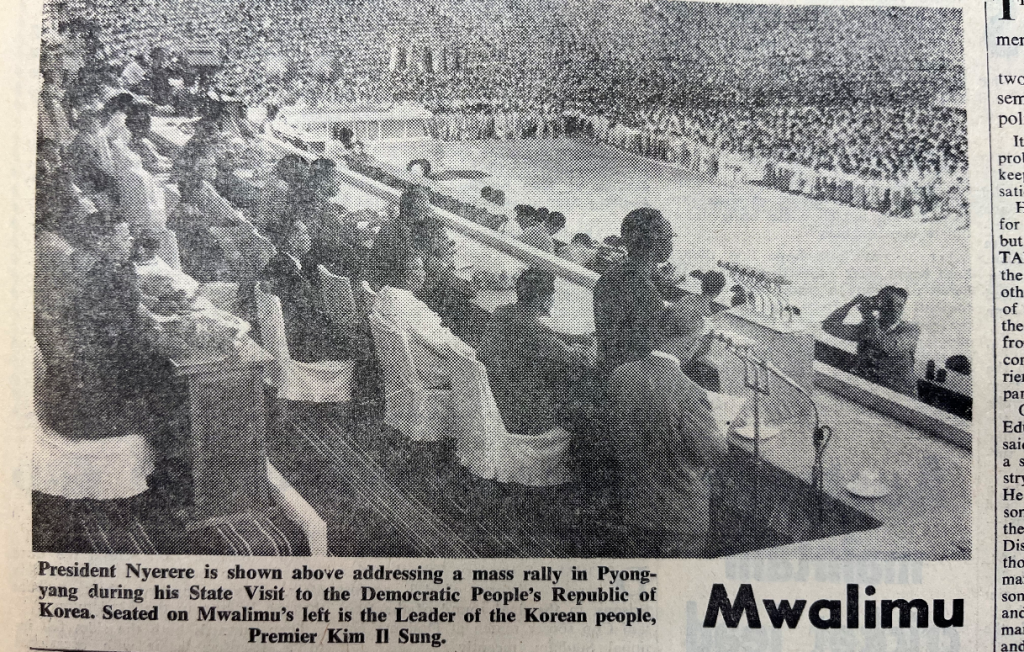

Julius Nyerere and Kim Il Sung congratulating the actors and actresses after watching a musical <Song of Paradise> in Mansudae Art Theater (Rodong Shinmun March 28, 1981), photograph by the author. Julius Nyerere addressing a speech in front of a mass rally in Pyongyang (The Nationalist, June 27, 1968), photograph by the author.

Julius Nyerere addressing a speech in front of a mass rally in Pyongyang (The Nationalist, June 27, 1968), photograph by the author.

An oil gusher in the Kirkuk district, Iraq, c. 1932 (Image: G. Eric and Edith Matson, Matson Photographic Collection, Library of Congress,

An oil gusher in the Kirkuk district, Iraq, c. 1932 (Image: G. Eric and Edith Matson, Matson Photographic Collection, Library of Congress,  The Kola Superdeep Borehole, welded shut, August 2012 (Image: Rakot13,

The Kola Superdeep Borehole, welded shut, August 2012 (Image: Rakot13,

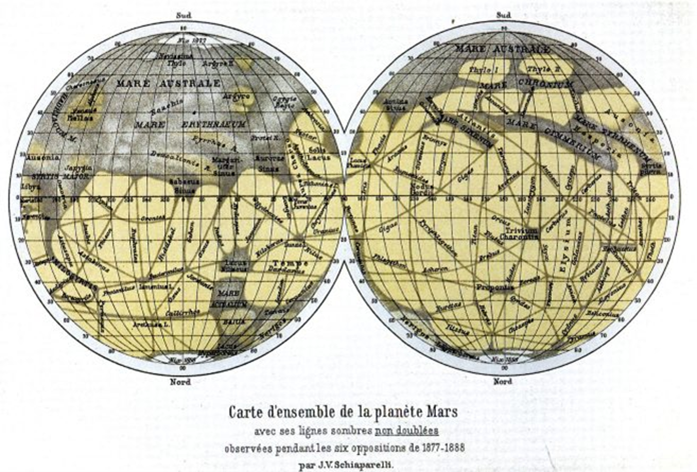

A depiction of the imagined system of canals on Mars. Title of Cosmopolitan Magazine XLIV, 4 (March 1908). https://www.loc.gov/item/cosmos000114.

This theory about life on Mars featured prominently in the discussion around 1900 about whether the new wireless communication technology could be used to communicate with extra-terrestrial beings — a discussion electrified by pioneers of that technology, like Nikola Tesla and Guglielmo Marconi, as well as the keen interest of the press. Already in 1892, Flammarion was convinced that the prospect of communicating with extra-terrestrials was ‘not at all absurd’.

A depiction of the imagined system of canals on Mars. Title of Cosmopolitan Magazine XLIV, 4 (March 1908). https://www.loc.gov/item/cosmos000114.

This theory about life on Mars featured prominently in the discussion around 1900 about whether the new wireless communication technology could be used to communicate with extra-terrestrial beings — a discussion electrified by pioneers of that technology, like Nikola Tesla and Guglielmo Marconi, as well as the keen interest of the press. Already in 1892, Flammarion was convinced that the prospect of communicating with extra-terrestrials was ‘not at all absurd’.

(Image courtesy of the

(Image courtesy of the