In

Blog 2023

david grillenberger

From 2 to 5 of August 2022, 20 scholars – PhD students, organisers

Anna Nübling &

Nikolai Brandes and student assistants – gathered in Munich during a scorching heat wave for global dis:connect’s inaugural summer school. Our engaging discussions and presentations emitted as much energy as the sun itself. Titled

Postcolonial interruptions? Decolonisation and global dis:connectivity, our very first summer school at global dis:connect focused on dis:connectivities in processes of decolonisation. The topic was apt, as decolonisation in itself is a very sudden (or sometimes very slow) interruption. It admits literal disconnects between former colonies and the empires that conquered them and simultaneously maintained connections to these empires. The process of decolonisation emphasises the colon in ‘dis:connectivity’ that, in this case, might represent the tension between independence and the continuation of relationships.

After a (literally) warm welcome from co-director Prof. Christopher Balme and a get together in our garden on Tuesday (2

. August), we gathered in global dis:connect’s library the next morning to hear the first master class by UCLA’s Ayala Levin. In her talk about

Continuity vs. discontinuity from colonialism to postcolonialisms, Levin emphasised African actors’ agency, as, for example, when choosing Israel and China as partners for architectural projects. Both nations have framed themselves as former colonial subjects and ‘developing countries’ fit to help African nations’ ‘development’.

Ayala Levin's master class (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger)

Ayala Levin's master class (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger)

Following Ayala’s master class and a short coffee break, Seung Hwan Ryu presented the first PhD project of the day, speaking on the relationship between North Korea and Tanzania. In his talk (

Surviving the disconnection. North Korea’s social internationalism in Tanzania during the Cold War — for a closer look,

check out Seung Hwan’s post summarising the talk on our

global dis:connect blog), Seung Hwan posed the question how North Korea was similar but different from other socialist globalisation projects. He emphasised ‘North Korea’s in-between geopolitical position’, between China and the USSR after the great disconnect that was the Sino-Soviet split. For some, Seung Hwan’s talk might have evoked memories of the fantastic Danish documentary

The Mole, which features present-day North Korea and its dealings in Africa, which have attracted the UN’s attention in 2020.

Next among the presentations was Lucas Rehnman, a Brazilian visual artist and curator, who presented his curatorial project. His project (

Unfinished Museum of Peripheral Modernity) on postcolonial modernist architecture in Guinea-Bissau poses an interesting what-if question: what if Bissau-Guineans did not simply follow external influences in the context of ‘foreign aid’ and ‘technical cooperation’ but instead worked actively and creatively as architects, establishing an architectural legacy that deserves attention?

After the lunch break, Adekunle Adeyemo presented his project on Israeli architect Arieh Sharon’s Obafemi Awolowo University Campus in Ile-Ife. Adekunle argued that the campus is a good example of modern architecture in Africa. He emphasised dis:connectivity when he argued that it was precisely the decolonial disconnect from the British empire that led Nigeria to look for new connections to Israel, as Ayala Levin also pointed out that morning. Adekunle framed the processes that led to Sharon’s designing the campus as a ‘Fanonian rupture’, as a crack in existing structures, which allows new things to fill the void.

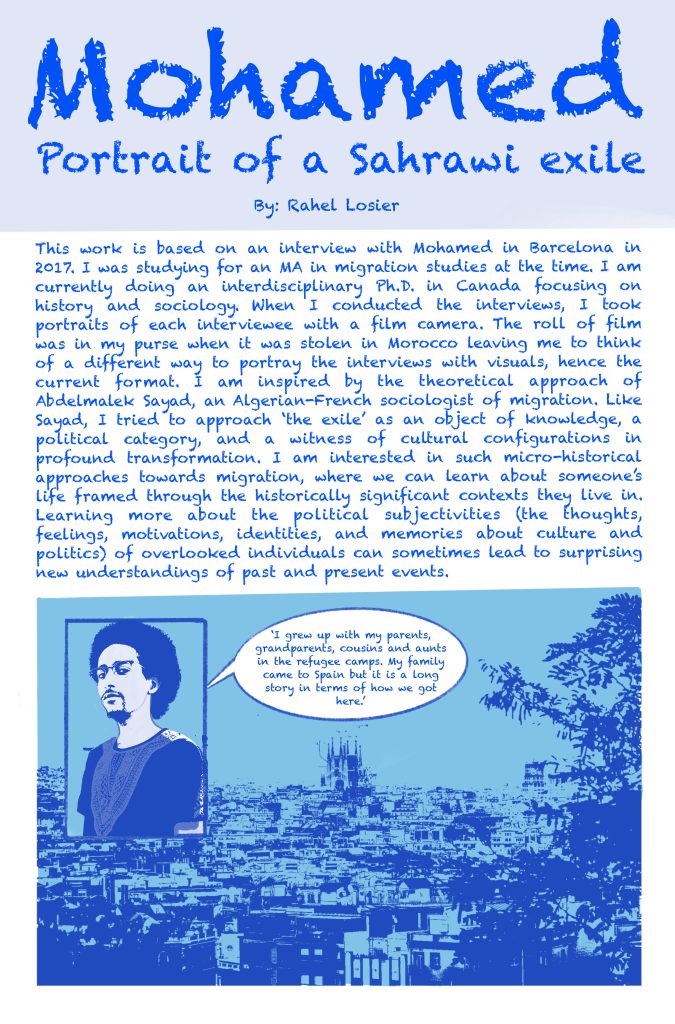

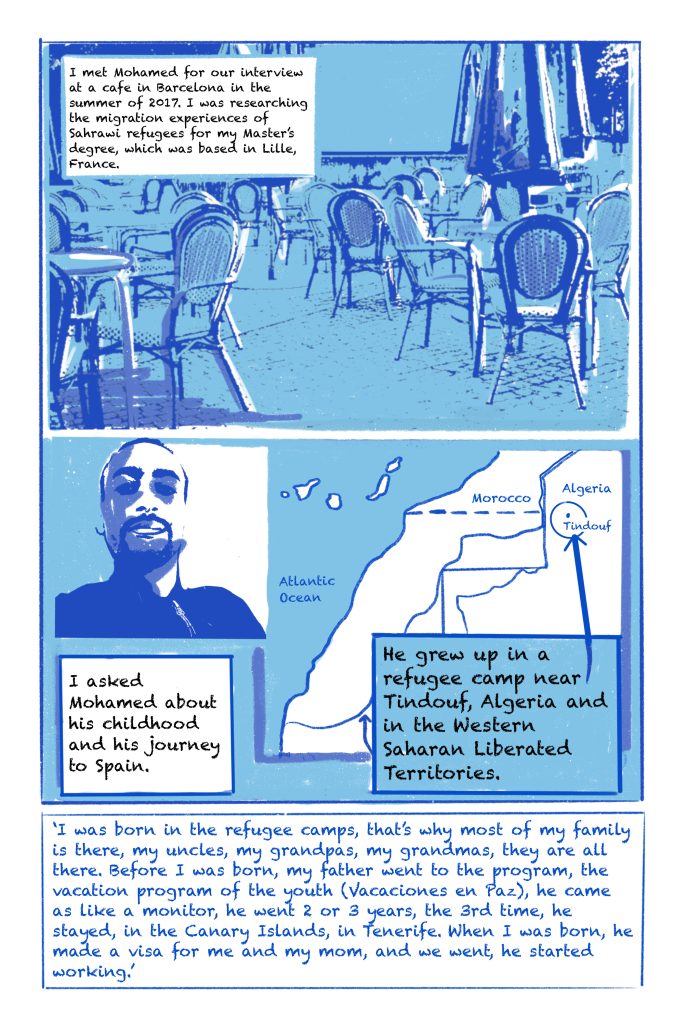

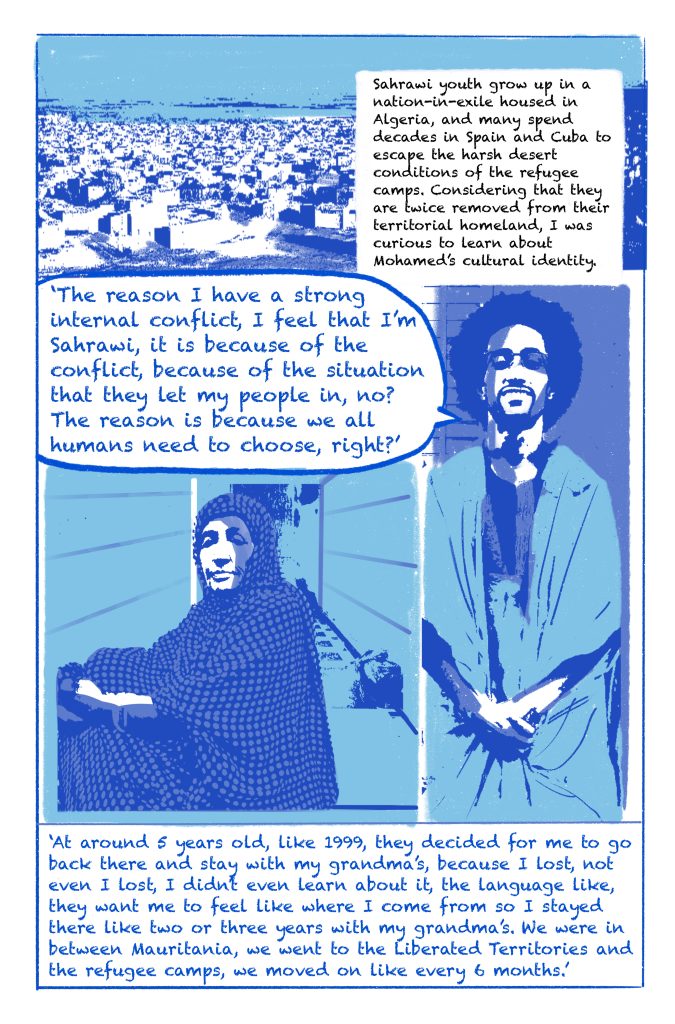

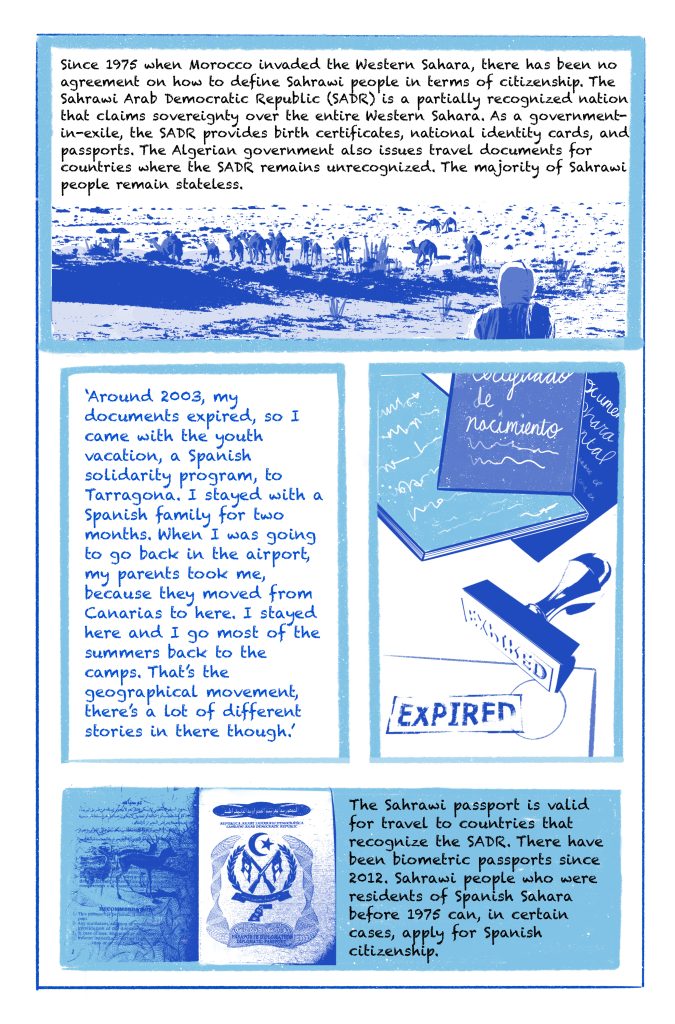

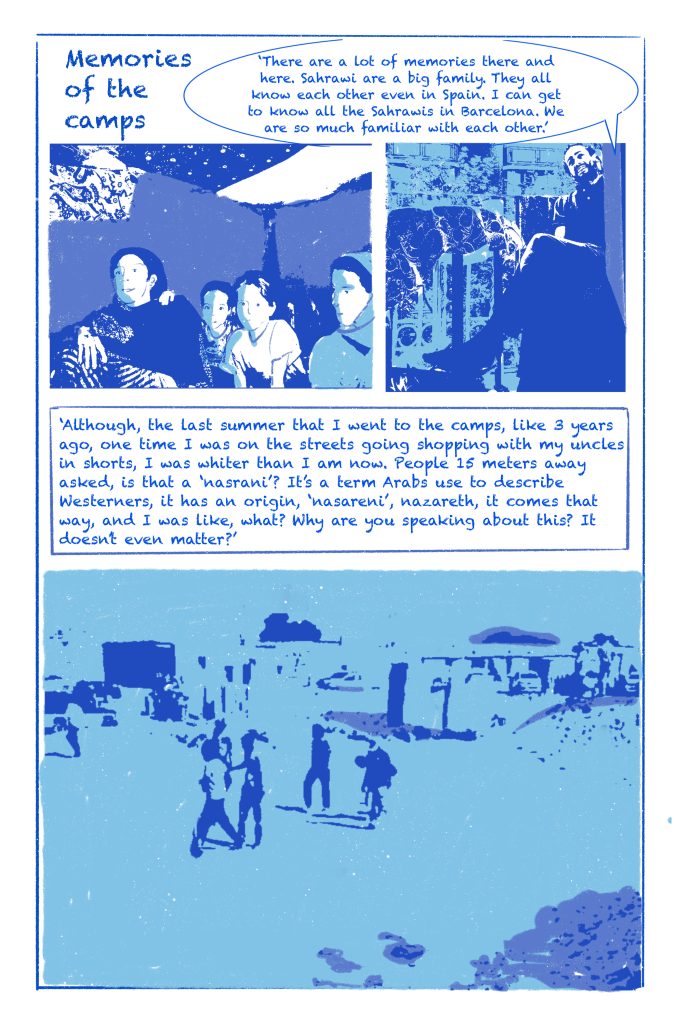

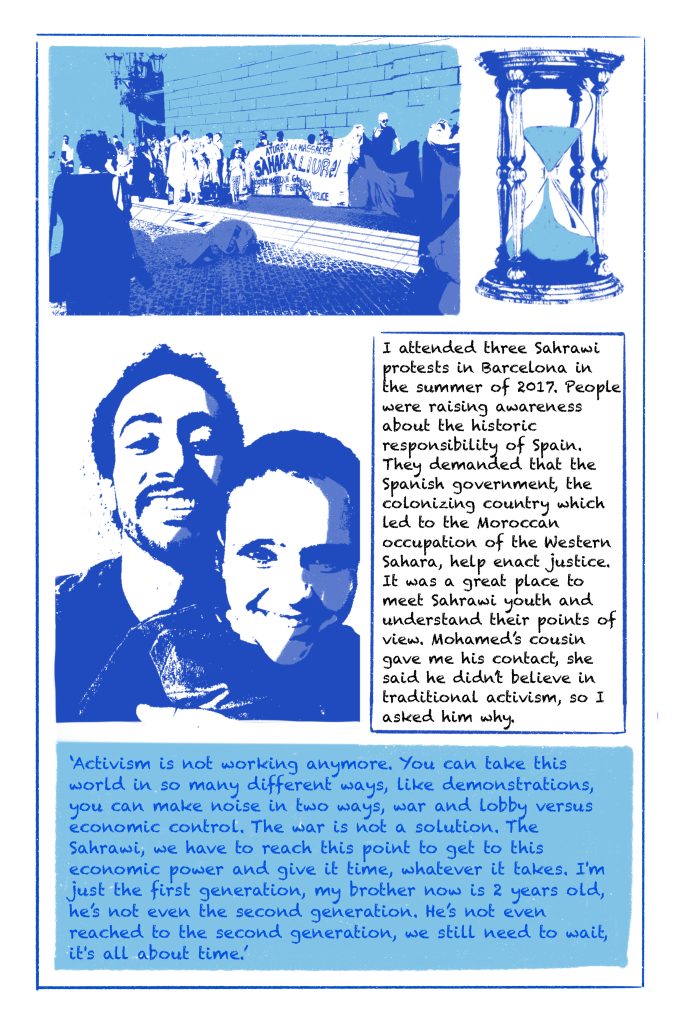

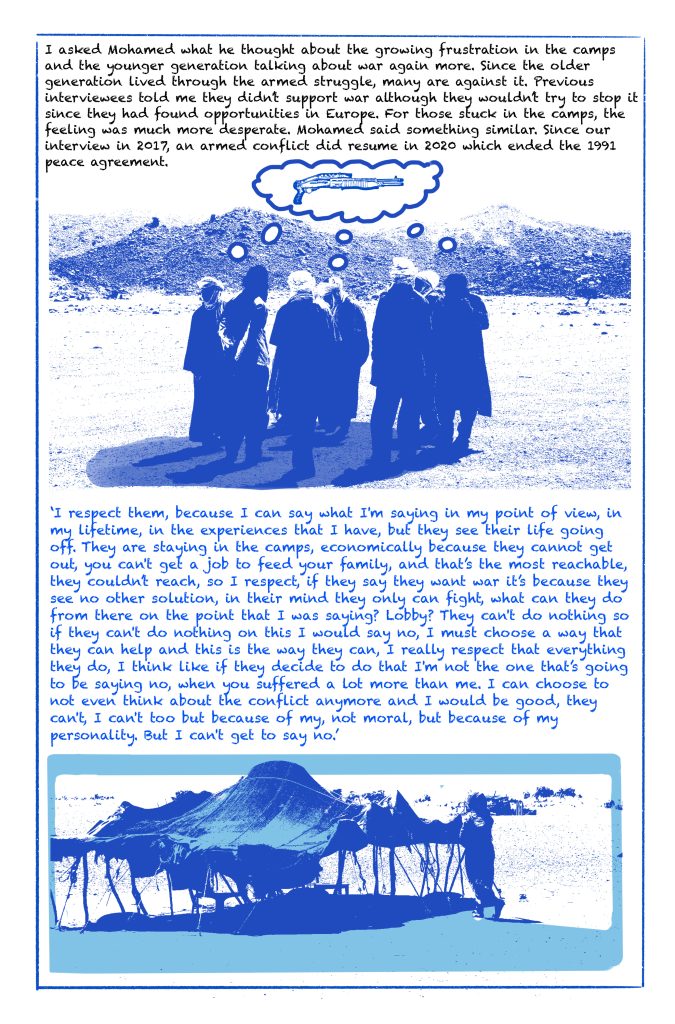

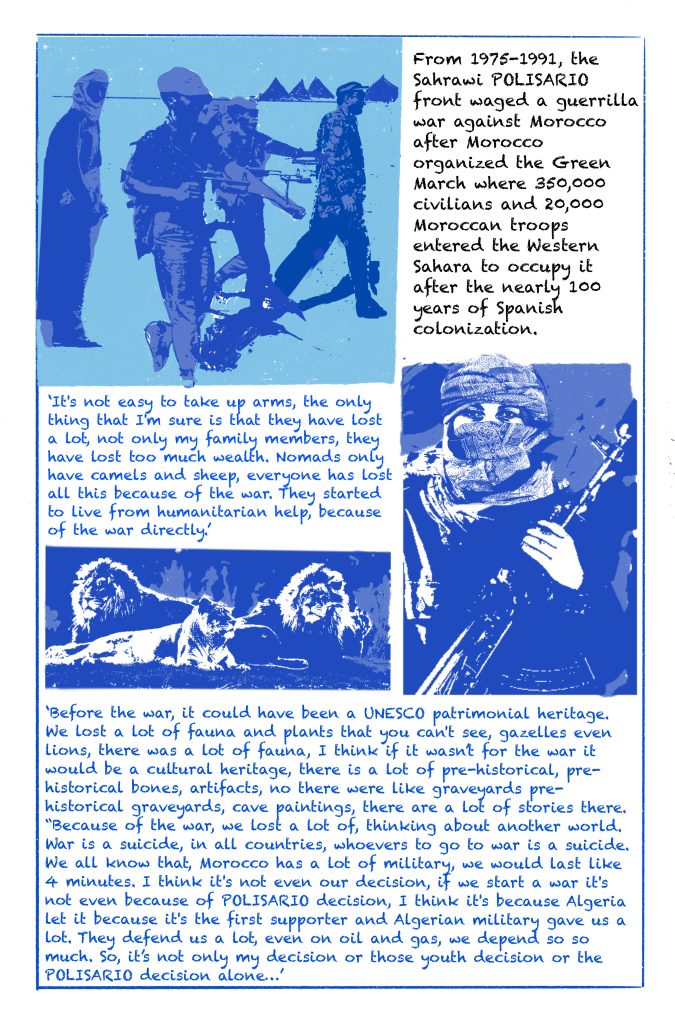

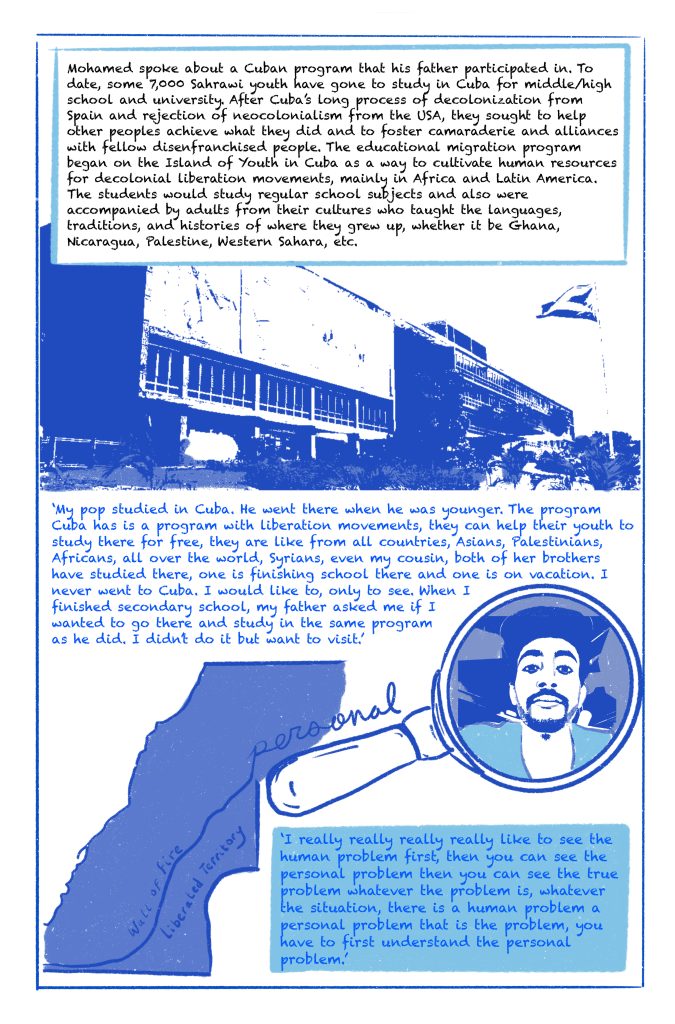

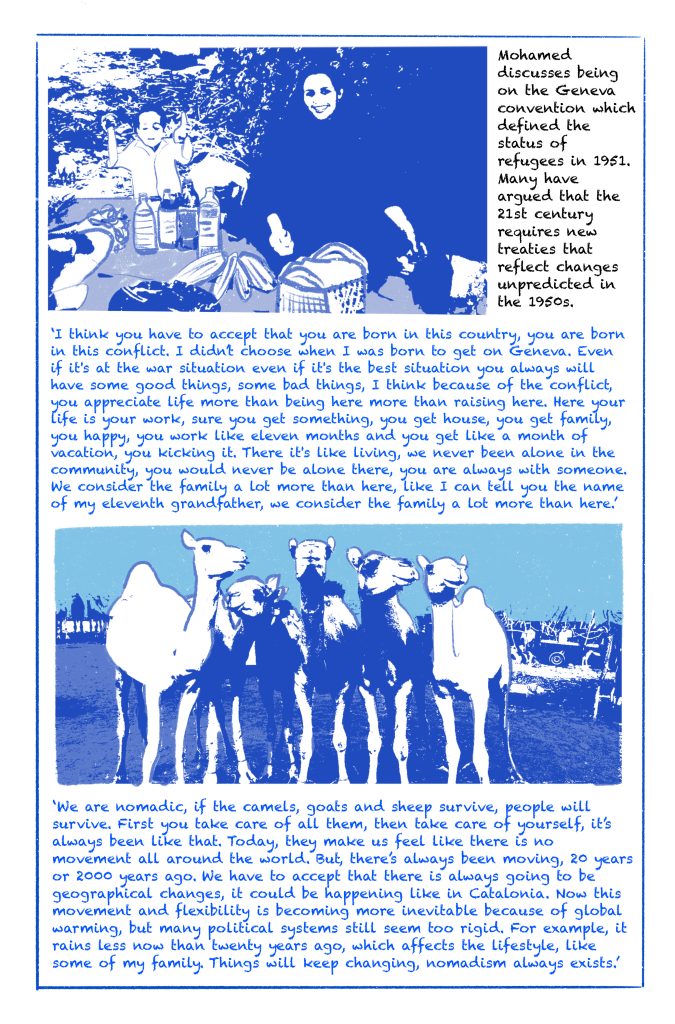

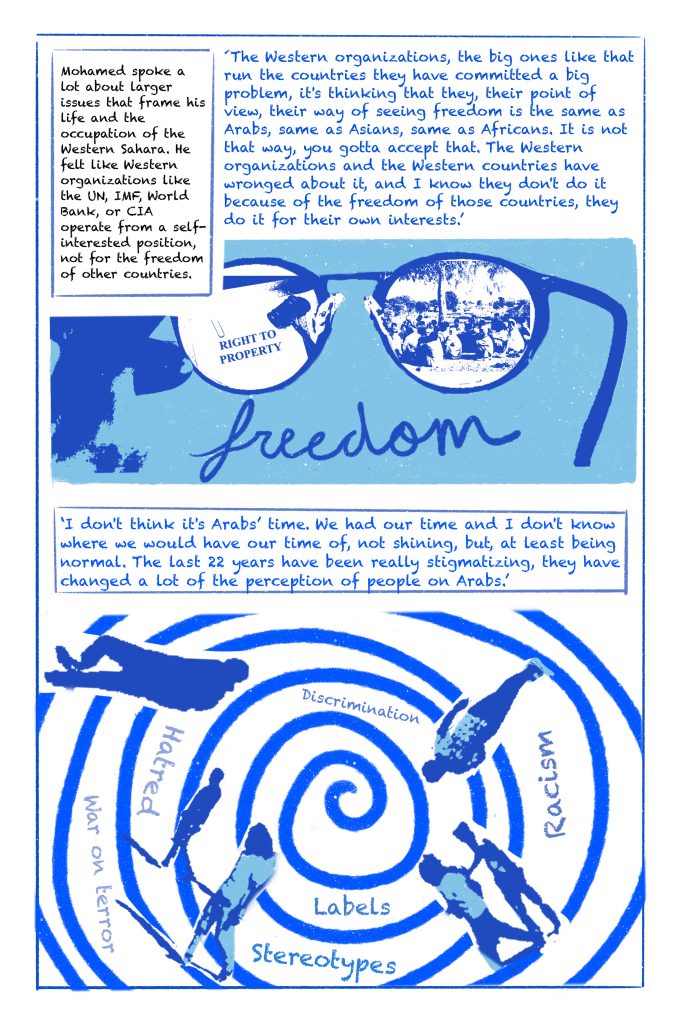

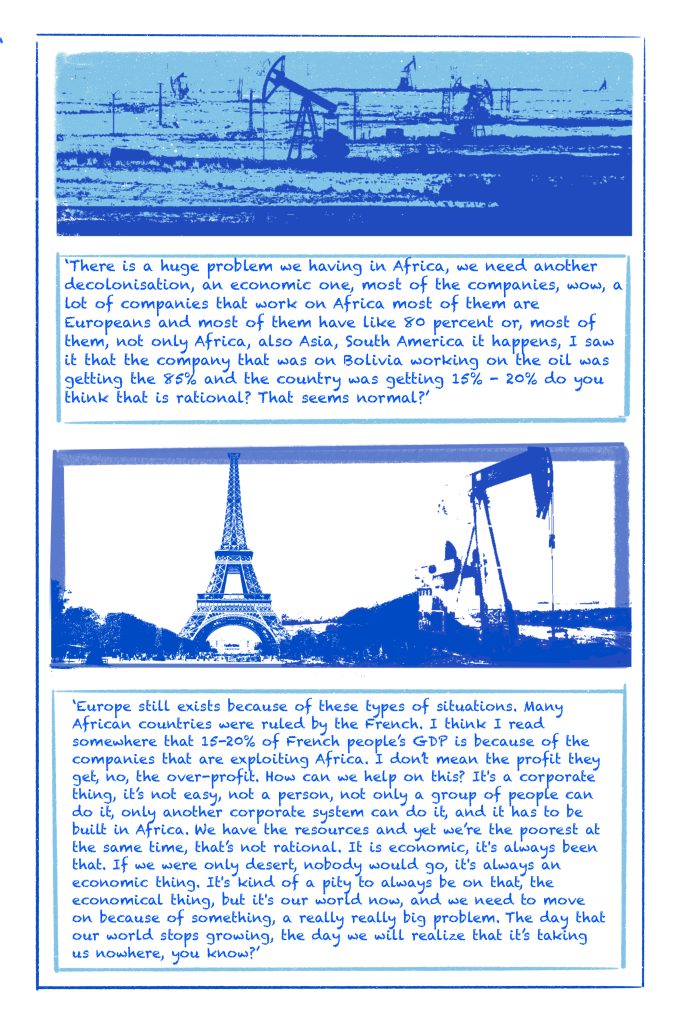

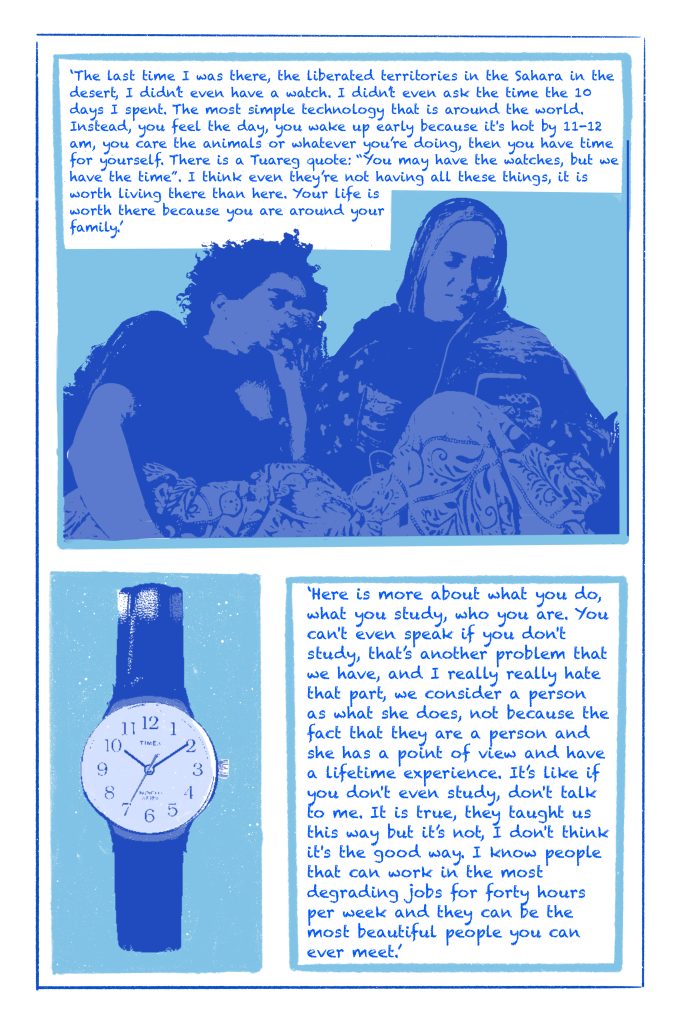

The last to present her project on our first full day together was Rahel Losier. Rahel spoke on the topic of ‘Sahrawi educational migration to Cuba from the 1970s to the present’. Chris Balme, one of the discussants, pointed out that the conflict in Western Sahara central to Rahel’s talk was one of our time’s ‘forgotten conflicts’ and that the relationship between Sahrawis and Cuba is a forgotten story. It is absent in history, one might say. And what could be more fitting than absences for the questions of global dis:connect? Rahel approached her research topic artistically as well and

created a brilliantly unique comic out of the interviews she conducted for her project. The presentation of her first comic also initiated an interesting discussion on whether and how artistic practice could help to better formulate research questions.

After an extended coffee break – much needed after engaging discussions and scholarly debates – Maurits van Bever Donker finished the day with a lecture, unintentionally representing the topic of ‘dis:connectivity’ in that he had to give his lecture remotely from South Africa. At 7:30 p.m., we all met for dinner and reflected on a long day of interesting projects and our new acquaintances.

The next day, Thursday, 4 August, started with decolonisation and epistemology. First up was another master class, this time held by Prof. Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni of Bayreuth University. He focused on three meta-topics: epistemology, decolonisation and dis:connectivity. Sabelo emphasised especially how knowledge itself could also be colonised and – referring to Dipesh Chakrabaty – suggested provincialising Europe in an institutional sense too, meaning that Western universities must reflect on the relationship between knowledge and power and how non-Western universities can get a more equal footing in global science.

The perfect follow-up to Sabelo’s talk was Tibelius Amutuhaire, who spoke on

The realities of higher education decolonisation: possibilities and challenges to decolonise university education in East Africa. Tibelius noted that, in most African universities, continuing eurocentrism is apparent in the exclusive use of Western (often foreign) languages to disseminate knowledge. Although, as Tibelius argued, African universities should lead the decolonisation efforts. In his master class, Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni also referred to the role of peer-reviewed journals, of which the most prestigious are still located in the West. Tibelius’s takeaway was that one of the main problems today is the continuous re-education of ‘false’ knowledge.

It was not only African countries and peoples who were subjected to colonialism, but also Asian countries like Pakistan, which was the focus of Talha Minas’ presentation. By focusing on the case study of Pakistan’s construction of its nationalist project, Talha discussed the theoretical and methodological challenges global history faces. He analysed the ‘master narrative’ of a Muslim claim to their own state in South Asia, especially in opposition to the British Empire. In the following discussion, gd:c co-director and one of this day’s discussants, Roland Wenzlhuemer argued that Talha’s topic could very well be a self-observational project that could tackle global history and its problems.

The afternoon started with Hannah Goetze’s presentation. Her talk focused on weaving, whose own literal connectivity makes it all the more interesting from the perspective of disconnections. Hannah analysed two different subjects: Lubaina Himid’s artpiece

cotton.com and Amalie Smith’s book

Thread Ripper. Weaving, Hannah argued, is closely connected to the internet as well as history and the future of computers in both works. So, in a way, they are stories about networks, be they woven or digital.

Up next was Flavia Elena Malusardi, whose research project aims to look at the cultural space

Dar el Fan in Beirut and how women’s identities were shaped there between postcolonialism and cosmopolitanism. For example, the anti-establishment movements of the 1960s also resonated in Beirut and intersected with decolonisation and the Cold War. Founded in 1967 by Janine Rubeiz, Dar el Fan also promoted ideas of gender equality and visibility and offered women a space where they could enjoy extensive freedoms in an otherwise often still conservative society.

The last of Thursday’s presentations focused on post-apartheid in South Africa. In his project, Brian Fulela analysed the novels of three different South African authors: K. Sello Duiker, Lgebetle Moele and Sifoso Mzobe. He examined the role and place of psychoanalysis in these novels and what psychoanalysis can bring to research on post-apartheid South Africa. Central to his project are feelings of trauma, loss and the subjectivity of post-apartheid, which are very much emotions and feelings of dis:connectivity.

The next day, Friday, began at the

Museum Fünf Kontinente in the centre of Munich. We were greeted by Stefan Eisenhofer and Karin Guggeis, who are responsible for the museum’s Africa and North America exhibitions. They showed us through the Africa exhibition and spoke on the difficulties of provenience research. Both also accompanied us back to

global dis:connect to attend the remaining presentations.

The gd:c summer school takes a field trip to the Museum Fünf Kontinente. (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger)

The gd:c summer school takes a field trip to the Museum Fünf Kontinente. (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger)

The first presentation of the day came from Lucía Correa, who is researching the ethnographic collections of French-Swiss Anthropologist Alfred Metraux. Ethnographic museums, Lucía argues, were a new way of thinking about human history with an emphasis on material culture. Meanwhile, Latin America is in the process of deconstruction and working with native communities to decolonise museums and their collections, since the colonialist perspective that motivated the founding of ethnographic museums is no longer viable. Metraux considered his collections a way to ‘remember’ the indigenous populations, which he perceived to be rapidly disappearing as a result of Western expansion in the 1930s. It is easy to see how absences – one of the key concepts informing dis:connectivity – play an important role in Lucía’s research and the future of ethnographic museums in general.

Next up was Claudia di Tosto’s talk on

Austerity and muddled optimism: the impact of decolonisation on Britain’s participation at the 1948 Venice Biennale. Claudia spoke on the recontextualisation of Britain’s exhibition in the context of decolonisation after World War II. In her presentation, she focused on one case study, namely 1948 and two artists that were prominently featured at the exhibition: J.M.W. Turner – a 19

th-century artist – and Henry Moore – a 20

th-century artist and contemporary painter at the time of the Biennale. Claudia argued that Britain used its 1948 pavilion to project the image of a nation that was using humanism as a rhetorical tool to both cover the demise of the empire and still lay a claim of superiority over its former colonies.

After our lunch break, Johanna Böttiger presented a very eloquently written essay in which she spoke on the topic of black dolls during the years of the Jim Crow laws in the USA. Children, argued Johanna, were an embodiment of coloniality and different stereotypes came with the colour of children’s skins – even in dolls, as black dolls were subjected to violence by white children. Certainly no child’s play, learned behavioural patterns like segregation or racism were also expressed in the form of children and dolls.

The last presentation of our time together was testament to the breadth of backgrounds the participants brought with them. Franziska Fennert, a German artist living in Indonesia, presented her project

Monumen Anthroposen as a film. The project consists of a ‘temple’, a monument complex, that is built in Indonesia and made from waste that is being transformed into a new product. Franziska’s aim was to redefine the relationship between humans, the planet and each other. In the long run, the ‘Anthropocene Monument’ should act as an infrastructure for upcycling that benefits its surrounding region.

Franziska’s presentation concluded our time together in Munich – at least from a scholarly perspective – and heralded the beginning of a convivial get-together with some traditional Bavarian music, beer and Brezen (soft pretzels). The participants agreed that the concept of dis:connectivity informed their research, and their varied backgrounds made for an engaging discussion and a lot of valuable comments.

It is almost staggering that a phenomenon such as decolonisation, which is so essentially dis:connective – the simultaneity of severing ties while still maintaining some and sometimes the stress they cause for the people involved – waited so long for the dis:connectivity treatment.

One, yet many (but not too many). (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger - the author in the back left with the snappy Hawaiian shirt)

One, yet many (but not too many). (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger - the author in the back left with the snappy Hawaiian shirt)

Continue Reading

A warm welcome to our new guest Katharina Wilkens who joins global dis:connect in early February.

A warm welcome to our new guest Katharina Wilkens who joins global dis:connect in early February.

A warm welcome to our new guest Katharina Wilkens who joins global dis:connect in early February.

A warm welcome to our new guest Katharina Wilkens who joins global dis:connect in early February.

On 8 February 2023, the Centre will hold a workshop centring on the representation of Istanbul in Germany through several exhibitions since 2000.

The global curatorial and artistic narratives about artists from Turkey have resulted in several critiques of European representational strategies that are predominately centred on geographical, cultural and national identities. In consequence, an increasing number of critical artistic and curatorial practices have emerged that attempt to transcend and challenge the art world's reductionist, Eurocentric tendencies, such as casting doubt on conventional stereotypes of East vs. West and the construction of 'Other'.

With global connectedness and disconnectedness as framing concepts, this workshop aims to explore the tensions that emerge from this dichotomy and how they relate to representations of Istanbul through several exhibitions in Germany since 2000. By exploring this context as a complex relationship of global interconnectivity, it aims to identify gaps, limitations and tensions in the globalisation processes of contemporary art from Turkey by considering the politics of art and exhibition politics in Europe.

This workshop's main objective is to contribute to a decolonial discussion on the globalization of contemporary art from Turkey by focusing on exhibition strategies and artistic forms of resistance. This involves sharing knowledge to understand globalisation and its intricate structures from a variety of perspectives. The workshop is a forum for debate and dialogue, bringing together scholars, artists, and curators to further develop this research and share from their own areas of expertise.

Where and when: Munich, 8 February 2023, 9.00 - 18.30

Language: English

Venue: Käte Hamburger Research Centre global dis:connect,

On 8 February 2023, the Centre will hold a workshop centring on the representation of Istanbul in Germany through several exhibitions since 2000.

The global curatorial and artistic narratives about artists from Turkey have resulted in several critiques of European representational strategies that are predominately centred on geographical, cultural and national identities. In consequence, an increasing number of critical artistic and curatorial practices have emerged that attempt to transcend and challenge the art world's reductionist, Eurocentric tendencies, such as casting doubt on conventional stereotypes of East vs. West and the construction of 'Other'.

With global connectedness and disconnectedness as framing concepts, this workshop aims to explore the tensions that emerge from this dichotomy and how they relate to representations of Istanbul through several exhibitions in Germany since 2000. By exploring this context as a complex relationship of global interconnectivity, it aims to identify gaps, limitations and tensions in the globalisation processes of contemporary art from Turkey by considering the politics of art and exhibition politics in Europe.

This workshop's main objective is to contribute to a decolonial discussion on the globalization of contemporary art from Turkey by focusing on exhibition strategies and artistic forms of resistance. This involves sharing knowledge to understand globalisation and its intricate structures from a variety of perspectives. The workshop is a forum for debate and dialogue, bringing together scholars, artists, and curators to further develop this research and share from their own areas of expertise.

Where and when: Munich, 8 February 2023, 9.00 - 18.30

Language: English

Venue: Käte Hamburger Research Centre global dis:connect,  Image: Martin Rempe

Image: Martin Rempe

Ayala Levin's master class (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger)

Ayala Levin's master class (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger) The gd:c summer school takes a field trip to the Museum Fünf Kontinente. (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger)

The gd:c summer school takes a field trip to the Museum Fünf Kontinente. (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger) One, yet many (but not too many). (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger - the author in the back left with the snappy Hawaiian shirt)

One, yet many (but not too many). (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger - the author in the back left with the snappy Hawaiian shirt)