In

Blog 2023

[Editor's note: this essay is the first in a series on the topic of dis:connected objects, curated by our own Burcu Dogramaci, Hanni Geiger and alumna fellow Änne Söll. The series originated with the workshop on dis:connected objects held in June 2022 and will appear in a special issue of static in May. Enjoy.]

petra löffler

‘… scientific objects are elusive and hard-won.’

(Lorraine Daston)

Magical corals

When the natural scientist Ernst Haeckel visited the shores of the Red Sea in March 1873, a dream came true for him: to see ‘the magical coral reefs’

[1] with his own eyes. However, he went not only to admire the beauty and diversity of the abundant coral species that have fascinated naturalists and artists since antiquity,

[2] but also to extract samples of his own from the sea. Corals are polyps (animals) that live in symbiosis with certain algae (plants), which they shelter in their calciferous exoskeletons, receiving nutrients in return. They live in colonies building the reefs that house many small species. Corals first have to be disconnected from their natural habitat to become collectible and classifiable scientific objects.

[3] My aim is to reconstruct the migration routes and transformations that the extracted corals had to undertake from their natural watery habitat in the shallows around the Sinai Peninsula to the dry natural history museums in Germany.

As I will show, Haeckel’s corals have passed through all commonplaces of Western science: the field as a space of exploration, the laboratory as a space of manipulation, the museum as a space of presentation and the archive as a space of circulation.

[4] In following their traces through inventory lists, correspondences and publications, I seek the ‘waves of action’ they are nevertheless able to release.

[5] As collection items, each specimen has its own history and ‘biography’ of extraction and migration from their areas of origin to the natural-history collections and museum repositories in the global North.

Figure 1: Madrepora (Acropora) squarrosa, collected 1873 by Ernst Haeckel near El Tor, Phyletic Museum, Jena (photo: Bernhard Bock).

Today, Haeckel’s extensive collection of corals is distributed across various scientific institutions, such as Berlin’s Natural History Museum and Jena’s Phyletic Museum. While some samples are exhibited as showpieces (figure 1), the majority of the impressive stock of corals is stored in repositories and thus disentangled once again (figure 2). Seen in this light, ‘his’ corals are not only disconnected but undead objects that raise questions about the entanglements of Western natural science and colonial politics in their extraction and involuntary migration.

Figure 2 a & b: Phyletic Museum, Jena, repository of Haeckel’s coral specimens (photo: Bernhard Bock).

With his 1873 journey, Haeckel explicitly followed in the footsteps of the natural scientist Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg, who had already travelled to the Red Sea in 1832 and had taken up quarters in El Tor to study coral species in their natural habitat.

[6] Haeckel returned to this village on the west coast of the Red Sea, which soon became a regional locus for coral research.

In his travel report, published in 1875, Haeckel complains about the ‘many and great difficulties’ of his journey to the scarcely populated Sinai Peninsula, which was, at least in the culturally biased eyes of the Western traveller, ‘mostly inhabited only by poor, half-wild Muhammedans’. ‘One must bring tents, servants, food and drinking water oneself in order to exist there. Nor is there any regular steamship connection between Suez and these wretched coastal places’.

[7] The alternative overland route through the Sinai desert seemed to him equally arduous and time-consuming and, as he notes, ‘the transport of the corals I wished to collect would have been very awkward on the camel’.

[8] Fortunately, the German naturalist could do without camels and servants because he could use the existing modern infrastructure of the country, which officially belonged to the Ottoman Empire. In his report, he describes hardships that were not too severe for a wealthy Western traveller. Haeckel could comfortably travel from Cairo to Suez with the railroad that opened in 1857, and he reached El Tor on board of an Egyptian navy steamship. These newly built imperial travel and transport routes, including the Suez Canal that opened in 1869, played an important part in the consolidation of colonial power.

Extracting corals

Arriving in El Tor, the whole harbour appeared to Haeckel as ‘a charming coral garden’.

[9] His report betrays how possessive he was of the local people, who built their houses and harbour facilities from dead stone corals: ‘Some of these wretched huts hold in a single wall a larger collection of beautiful coral blocks than can be found in many European museums. We would have loved to buy up the whole village, pack it up and send it home’.

[10]

This did not happen, however, because the zoologist was even more excited about the abundance of coral communities living in the reefs fringing the village. In order to extract them from their natural habitat, he relied on local fishermen, who provided boats and were experienced pearl divers. As Haeckel reports, ‘[t]hey were neither equipped with diving bells nor with scaphander or other diving apparatus; but they swam so excellently, could stay under water so long and knew so skilfully how to detach even larger corals from their points of attachment that they never resurfaced without surprising us with new splendid gifts of coral’.

[11]

I am not as concerned with Haeckel’s admiration for the skill of the local divers as with his remark on the magnificent corals as ‘splendid gifts’. As anthropologist Nicholas Thomas points out, gifts are always part of complex exchange relations, that is ‘a political process, one in which wider relationships are expressed and negotiated in a personal encounter’.

[12] Moreover, Haeckel describes the coral extraction as a fabulously successful treasure hunt: ‘As soon as we have indicated the desired object to our divers, they jump down. [...] In a few hours our boats are filled with the most precious treasures’.

[13] Not only does he claim ownership of the corals, he extends this notion to those who did the work, whom he unhesitatingly refers to as ‘our divers’. In Haeckel’s rationalist Western worldview, the evocation of nature’s wealth is the prerequisite of the ability to freely take possession of it. Claims of ownership overlap with ideas of the assumed superiority of Western economy, culture and science that are entangled with regimes of coloniality.

[14] Haeckel’s journey stood under the protection of the Egyptian regime, which also ruled over the Greek-Arab population of the Sinai. His travel report is dedicated to the Ottoman ruler Ismail Pasha for good reason. As a Western scientist, Haeckel undoubtedly profited from colonial power, even though he explicitly acknowledged the valuable support and hospitality of the local fishermen of El Tor.

[15]

Collecting corals

Corals are a promising research object for the art-loving zoologist because of their immense diversity and their special way of living in colonies.

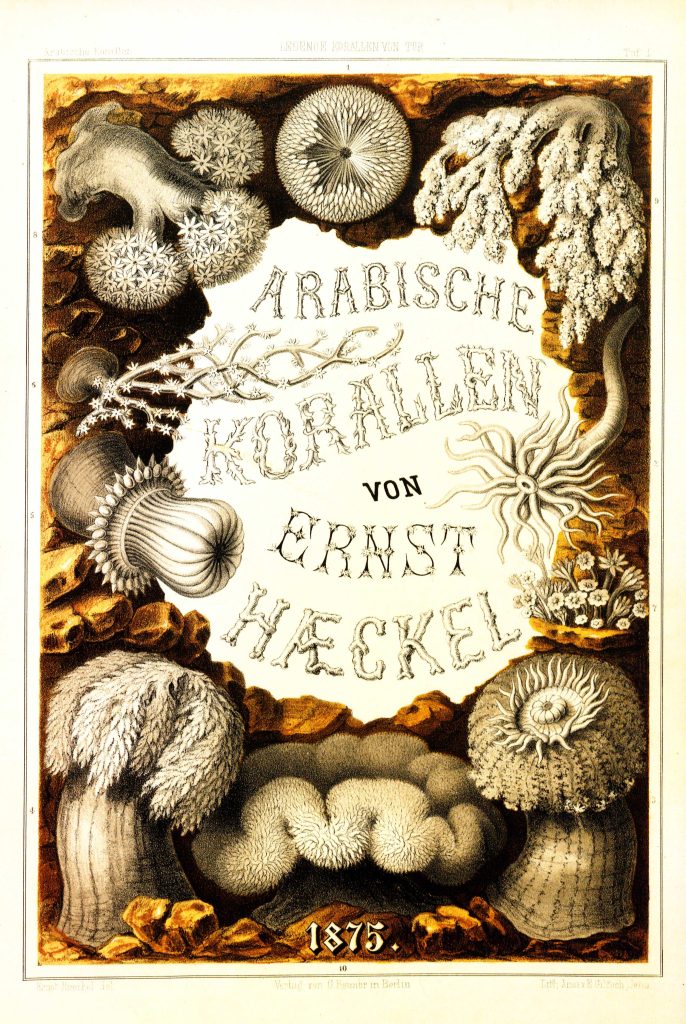

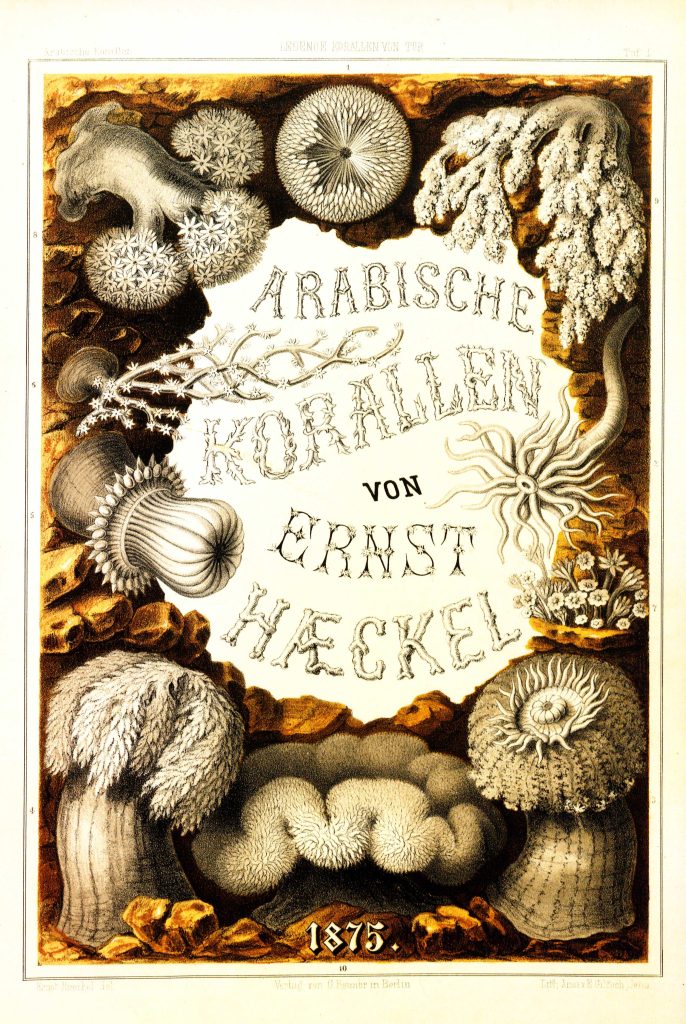

[16] The title page of

Arabische Korallen (

Arabian Corals), designed by Haeckel himself, gives an impression of the richness of forms of these so-called anthozoans or floral animals (figure 3). His admiration for these diverse species was partly ignited by their metabolism (each individual polyp has a stomach and is therefore a person in a strictly biological sense) and because these coral persons settle in large colonies on submarine rocks.

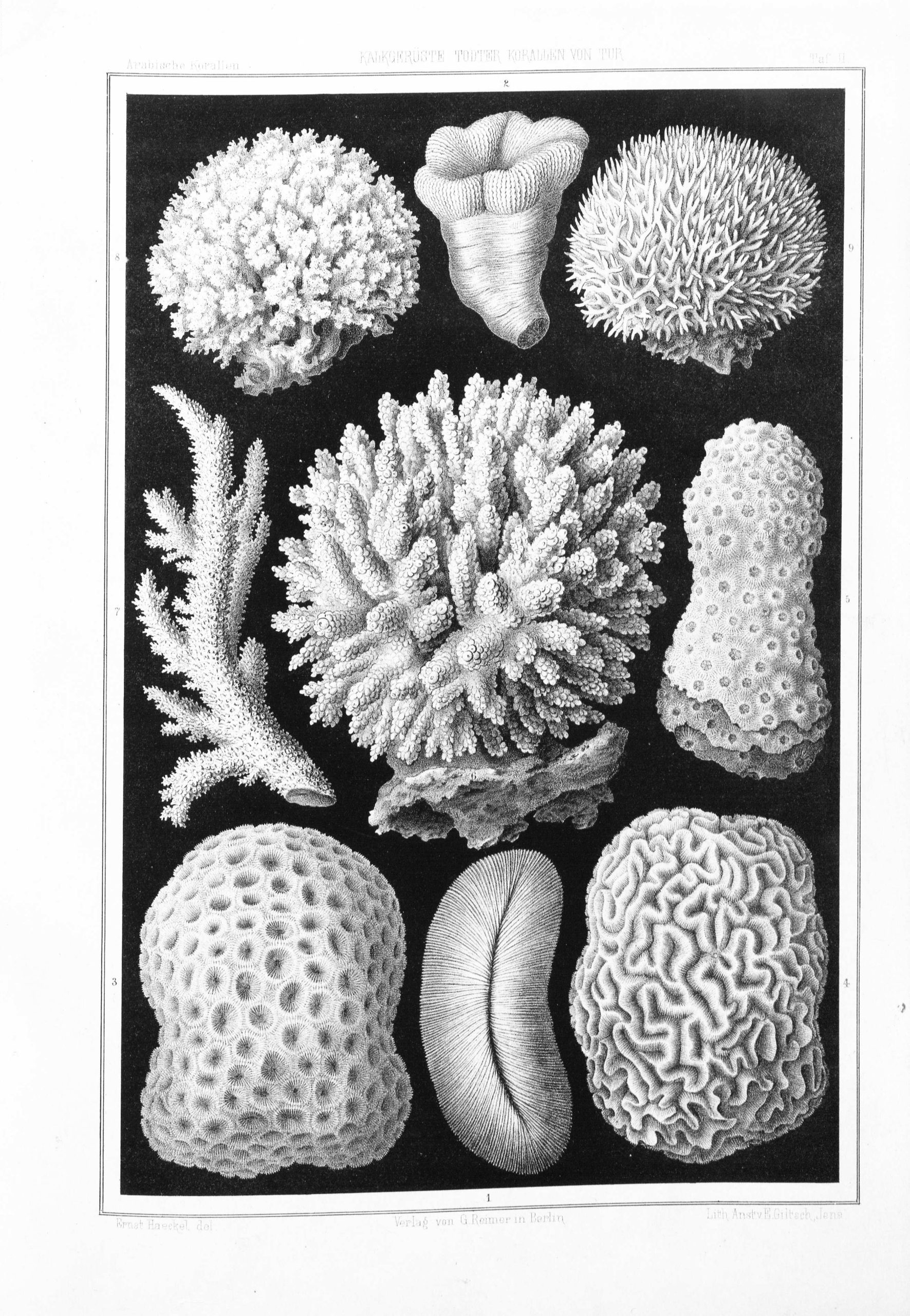

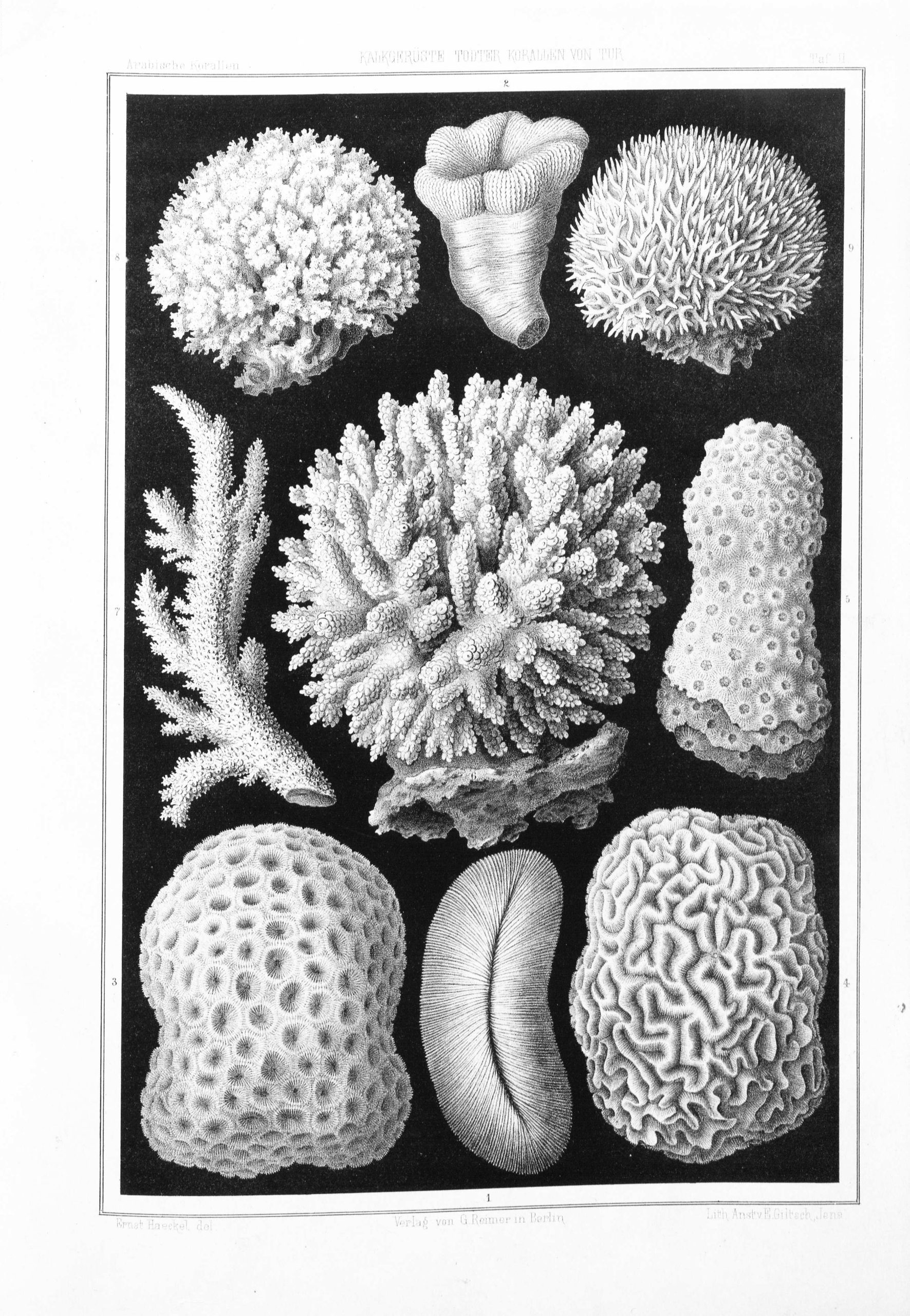

Figure 3: Ernst Heackel: Kalkgerüste toter Korallen von Tur (Calcareous scaffolds of dead corals from El Tor), Arabian Corals, 1875, plate II (scan: Petra Löffler).

Haeckel, who promoted Darwin’s theory of evolution and shared with the English naturalist his admiration for corals as reef architects,

[17] coined the term ‘ecology’.

[18] He became especially interested in coral communities as habitats for various other small marine species that perform a kind of ‘social democracy’.

[19] With this metaphor, corals enter the realm of politics and become a model for a civil society with equal members. At the same time, these coral communities reminded Haeckel of a miniature ‘zoological museum’.

[20] Exactly this last notion turns living corals into a scientific object even before their extraction.

The illustrations in Haeckel’s travelogue represent the richness of forms and the specific morphology of corals (figure 4). What is particularly revealing, however, is how he transformed them into scientific objects and proceeded as a collector. To transport the removed coral specimen, Haeckel already made extensive arrangements before his arrival in El Tor and ordered a great quantity of wooden boxes and big glass jars. The transportation of marine species required special practices, logistics and knowledge of their needs.

[21] The fact that in the end only twelve boxes with both wet and dry specimens arrived in his hometown of Jena, as he noted with regret,

[22] shows the scale of his ambition as a collector.

Figure 4: Ernst Heackel: Arabische Korallen (Arabian Corals), 1875, title page (scan: Petra Löffler).

Naturalists can prove themselves experts by collecting specific specimens and identifying new species. The zoologist Carl Benjamin Klunzinger, for instance, who also travelled to El Tor, praised professional collecting as a serious scientific activity. He documented his collecting activities in

Bilder aus Oberägypten, der Wüste und dem Rothen Meere (

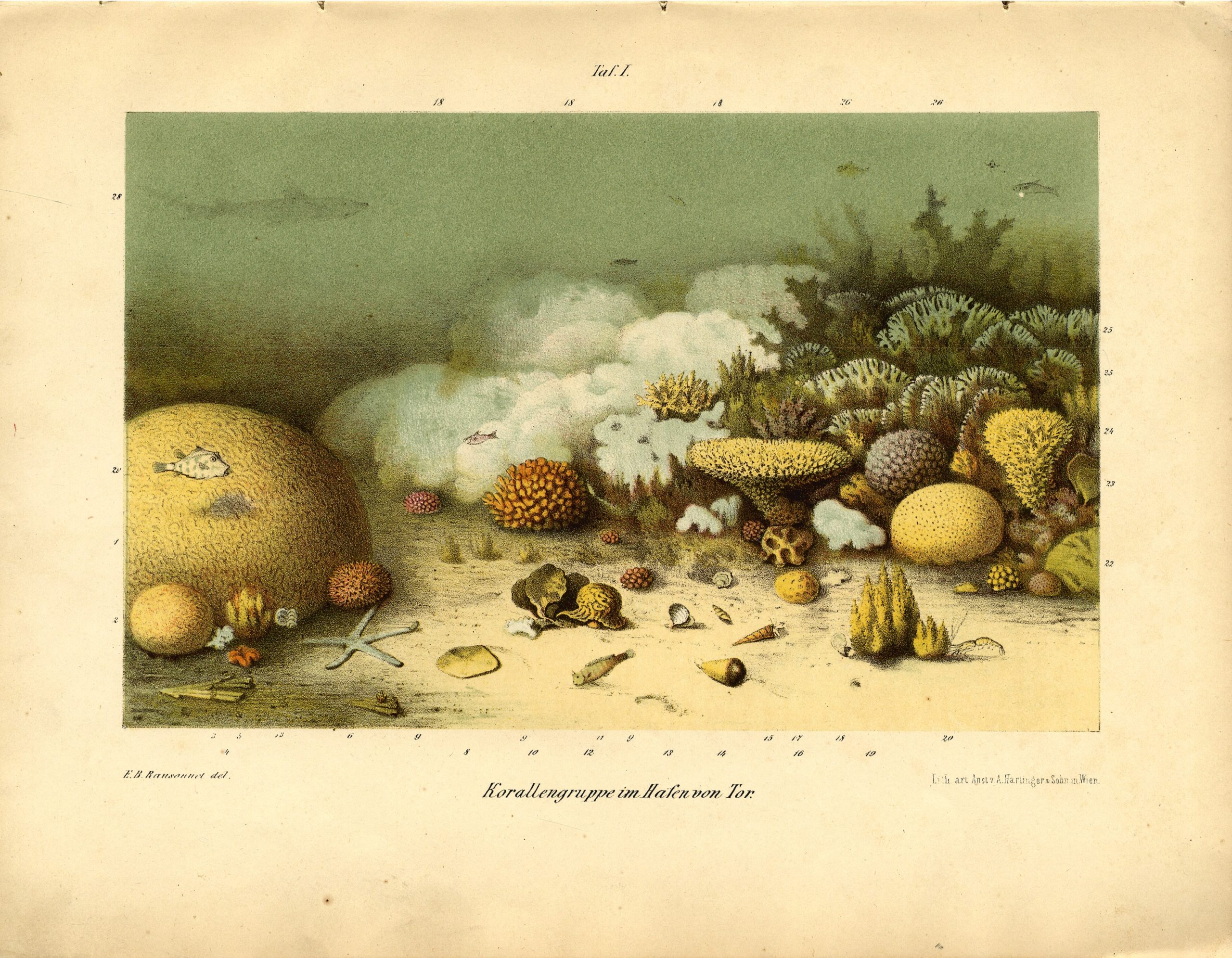

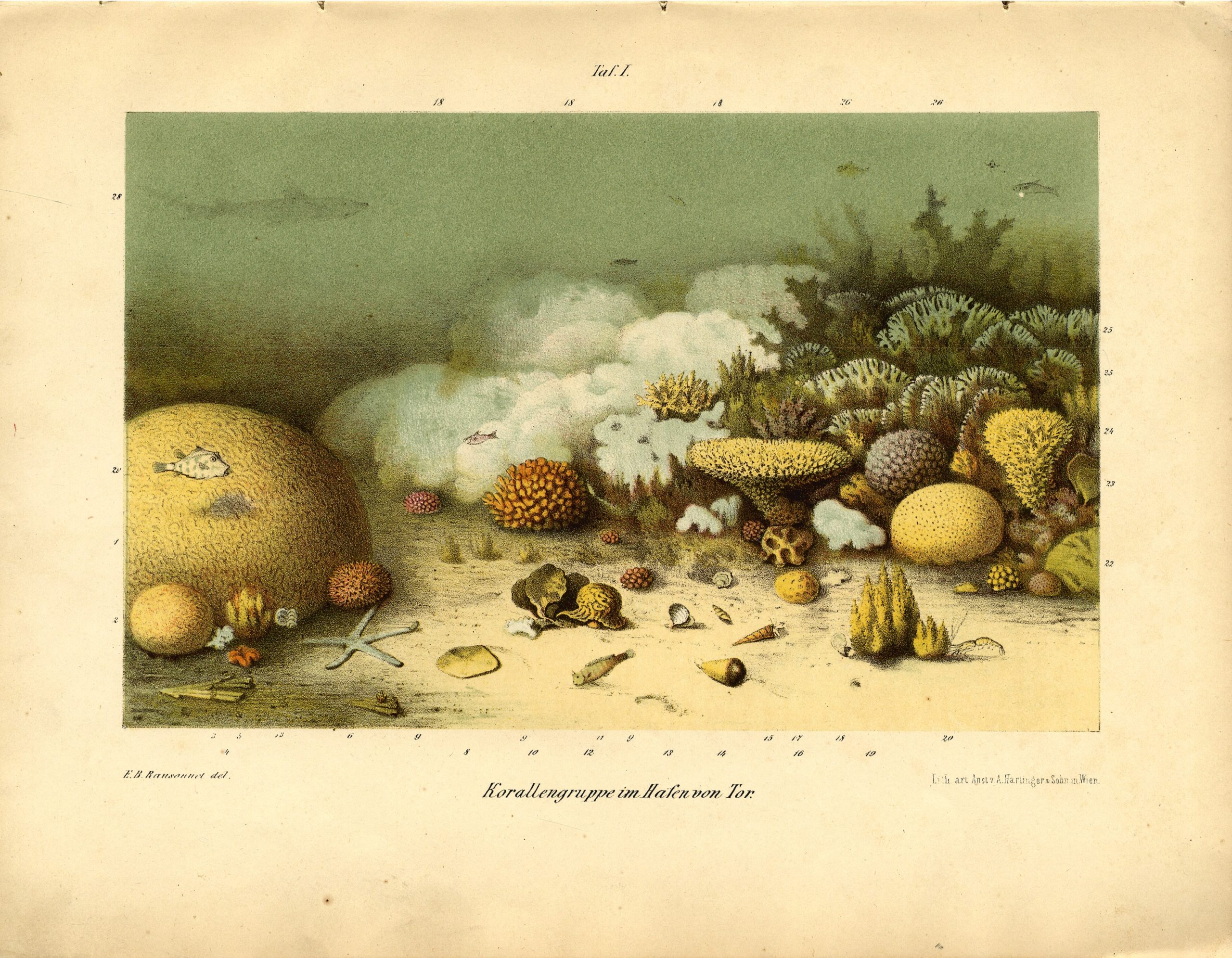

Images from Upper Egypt, the Desert and the Red Sea), published in 1877 with 22 drawings. Extensive collecting of specimens was primarily intended to benefit scientific teaching and object lessons. But corals die quickly in the air and lose their colour. To depict their diverse forms and vivid colours, the explorer and painter Eugen Baron Ransonnet-Villez developed a special diving apparatus and made underwater drawings on site. Nevertheless, the colourful depictions of reef colonies that adorn the publications of Ransonnet-Villez (1863) and Haeckel are idealised images that underline the necessity of visual representations to advance scientific knowledge (figure 5).

[23]

Figure 5: Eugen Baron Ransonnet-Villez: Reise von Kairo nach Tor zu den Korallenbänken des rothen Meeres (Journey from Cairo to Tor to the Coral Banks of the Red Sea), 1863, plate I.

Regimes of circulation

What did Haeckel do in Jena, where he had held a professorship in zoology since 1865, with all the corals he had appropriated? His collection was initially used for the morphological classification of a phylum whose diversity he had always admired. Some particularly splendid specimens became showpieces in his Villa Medusa. Some are also currently exhibited in the Haeckel Museum in Jena. Others ended up in the Phyletic Museum, which Haeckel founded in 1908. There, 128 coral specimens are still kept, among them 25 from El Tor.

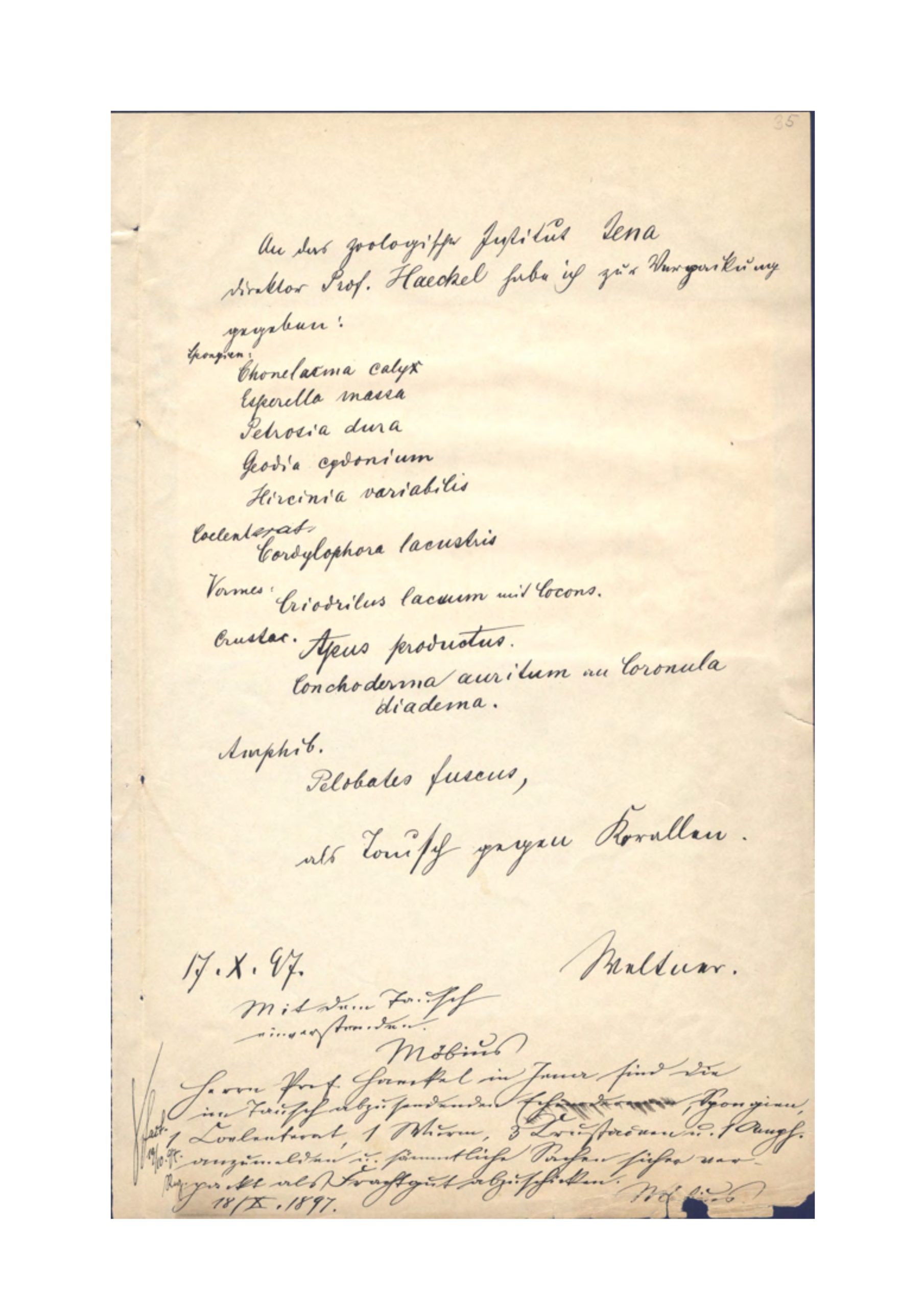

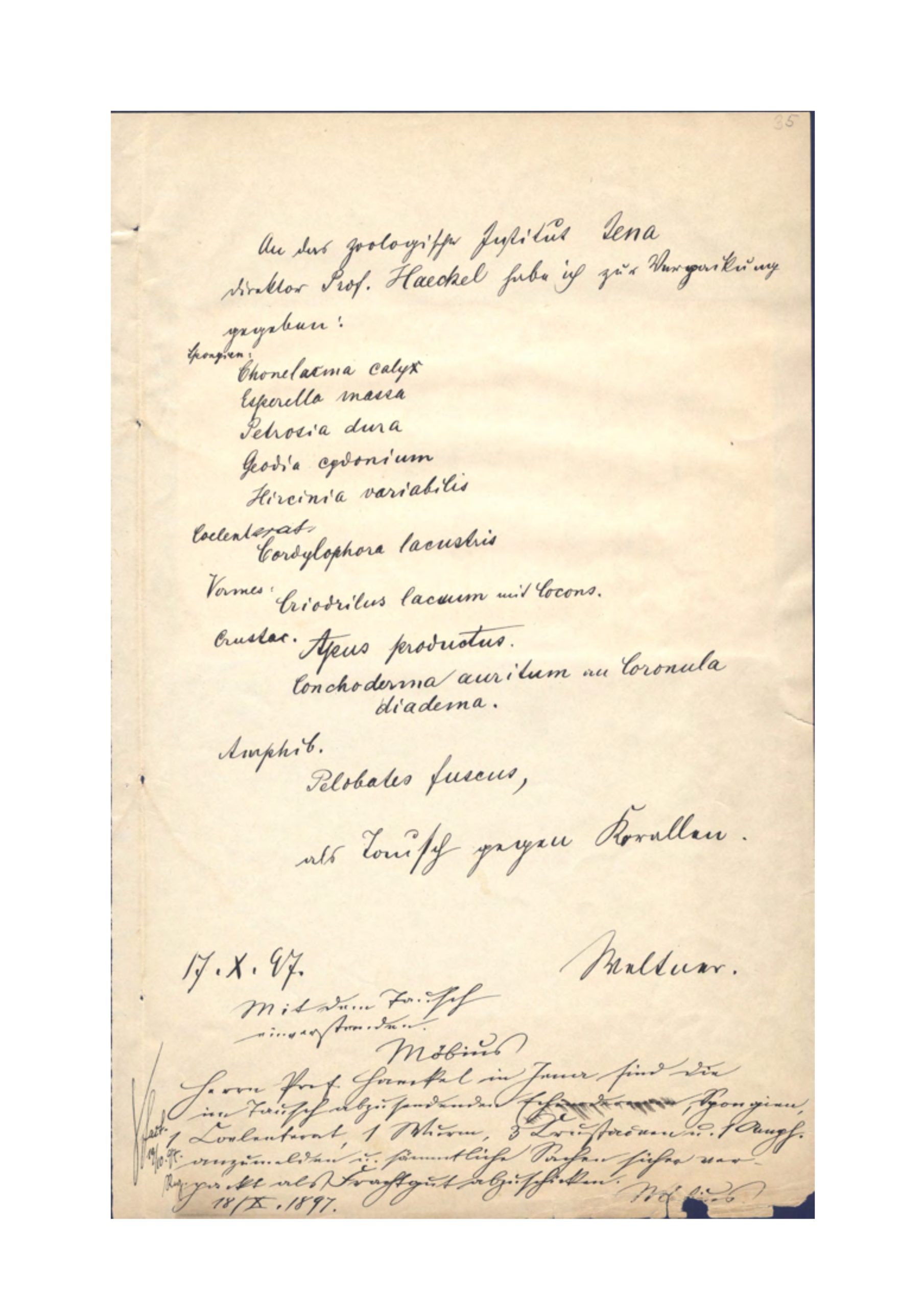

[24] He gave other pieces to the Natural History Museum in Berlin, which opened in 1889. Thereupon a lively correspondence began between the natural scientists, in which the exchange of collection objects was a recurring topic. On 25 November 1897, for instance, Karl Möbius, the director of its zoological collections at the time, thanked Haeckel in a short letter for sending corals and jellyfish to Berlin. Many such letters that Haeckel wrote contain long lists of the specimens exchanged and testify to the great interest in their circulation (figure 6). To this day, Haeckel’s corals from El Tor are kept in the archive cabinet 98/93 at the Natural History Museum.

[25]

Figure 6: List of marine invertebrates’ specimens given to Ernst Haeckel by the Berlin Museum of Natural History in exchange with coral specimens (Letter from 10/17/1897 with a note by Karl Möbius from 10/18/1897) (source: Berlin Museum of Natural History)

In order to demonstrate the political significance of the natural sciences, large natural-history collections were important prestige projects for the newly founded scientific institutions, such as the afore mentioned Berlin Museum of Natural History or the Phyletic Museum in Jena.

[26] These collections were intended to illustrate nature’s diversity and general order in detail. In short, they served to open the great book of nature and make it scientifically readable. To present the taxonomic order of species, it seemed necessary for biologists to collect as many specimens as possible and to exchange them with other researchers, even if this exchange dissolved the original collection. Haeckel’s collection is only recognisable today through inventory lists.

As natural-history objects disconnected from their natural habitat, these specimens only attain scientific significance within the taxonomic scheme as developed by Carl Linné in the 18th century, which remained the prevailing mode of ordering biological objects until the end of the 19th century.

[27] Showcases in natural history museums and the storage system in their repositories still represent this Western ‘order of things’. In addition, museum displays try to reanimate the vivid natural habitat of coral reefs by creating dioramas or VR experiences for their visitors even today. In times of anthropogenic climate change, however, coral reefs are suffering from the heating and acidification of the ocean and will soon be extinct, many marine scientists suspect.

[28] The discovery of new species and variants has been a crucial task in biology as a discipline of Western science for hundreds of years and was, as I have demonstrated, intricately connected to colonial claims.

Now marine biologists search for corals that are more resistant to global warming and its effects and to extract them from their marine habitats to breed new species. Calling the invention of corals in the laboratory – in Darwin’s footsteps – ‘assisted evolution’, they involuntary add a new chapter to the marginalised colonial history of the natural sciences.

[29]

[1] Ernst Haeckel,

Arabische Korallen (Berlin: Verlag von G. Reimer, 1875), 23, All translations from Haeckel’s Arabische Korallen (Arabian Corals) are by the author.

[2] Marion Endt-Jones,

Coral: Something Rich and Strange (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013).

[3] On the making of scientific objects and their biographies, see: Igor Kopytoff, ‘The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process’, in

The Social Life of Things. Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. Arjun Appadurai (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge), 64–91 and ; Lorraine Daston, ed.,

Biographies of Scientific Objects (Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press, 2000).

[4] See: David Livingstone,

Putting Science in Place: Geographies of Scientific Knowledge (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003).

[5] I draw here on Bruno Latour’s claim that living and non-living entities are entangled in networks and able to act: Bruno Latour,

Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2017), 101; See also: Bruno Latour,

Pandora’s Hope: Essays in the Reality of Science Studies (Cambridge/London: Harvard University Press, 1999).

[6] Ehrenberg published his findings on the coral reef communities of the Red Sea in 1834. At the same time, from 1832 to 1836, Charles Darwin made his circumnavigation on the HMS Beagle and researched the formation and distribution of coral reefs around the world, see: Charles Darwin,

The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs: Being the First Part of the Geology of the Voyage of the Beagle (1832-1836) (London: Smith, Elder & Co, 1842); He also collected coral specimens as evidence for his hypothesis of how the different reef types formed. They are now in the holdings of the Natural History Museum in London, see: Hayley Dunning, ‘Charles Darwin’s Coral Conundrum’, Natural History Museum, 23 January 2023, https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/charles-darwin-coral-conundrum.html.

[7] Haeckel,

Arabische Korallen, 23–24.

[8] Haeckel, 24.

[9] Haeckel, 29.

[10] Haeckel, 30.

[11] Haeckel, 30.

[12] Nicholas Thomas,

Entangled Objects: Exchange, Material Culture, and Colonialism in the Pacific (Cambridge/London: Havard University Press, 1991), 7.

[13] Haeckel,

Arabische Korallen, 31.

[14] Walter D. Mignolo defines coloniality as ‘the underlying logic of the foundation and unfolding of Western civilization from the Renaissance to today of which historical colonialisms have been a constitutive, although down-played, dimension’: Walter D. Mignolo,

The Darker Side of Western Modernity. Global Futures, Decolonial Options (Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2011), 2.

[15] In the 1880s, marine biologist Johannes Walther visited El Tor again to undertake a survey on the geological formation of the fringing-reef-rich Red Sea. From Suez, he took the route through the desert with camels. In his report, Walther thanked the German ‘consulate agent’ in El Tor, Hannén, and his sons for their assistance with coral diving: Johannes Walther,

Die Korallenriffe Der Sinaihalbinsel: Geologische Und Biologische Betrachtungen (Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1888), 471.

[16] At the time of the publication of Arabian Corals, ‘more than one thousand different living coral species, and the fossilised skeletons of more than three thousand extinct species’ were already known: Haeckel,

Arabische Korallen, 3.

[17] On the discovery of the reef-building activity of corals in the 18th century by explorers such as Johann Reinhold Forster or Louis-Antoine Bougainville, see: Alistair Sponsel, ‘From Cook to Cousteau: The Many Lives of Coral Reefs’, in

Fluid Frontiers: New Currents in Marine Environmental History, ed. John R. Gillis and Franziska Torma (Cambridge: The White Horse Press, 2015), 137–61.

[18] In his Generelle Morphologie der Organismen (General Morphology of Organisms), Haeckel defines ecology as ‘the general science of the interdependence among organisms’: Ernst Haeckel,

Generelle Morphologie Der Organismen: Allgemeine Grundzüge Der Organischen Formenwissenschaft, Mechanisch Begründet Durch Die von Charles Darwin Reformirte Descendenztheorie, Vol. II: Allgemeine Entwickelungsgeschichte der Organismen (Verlag von G. Reimer, 1866), 236, Authors Translation.

[19] Haeckel,

Arabische Korallen, 20.

[20] Haeckel, 20,35.

[21] See: Mareiken Vennen,

Das Aquarium: Praktiken, Techniken Und Medien Der Wissensproduktion (1840 – 1910) (Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2018), 235–63.

[22] Haeckel,

Arabische Korallen, 35.

[23] For a deeper understanding of the importance of visual representations in Haeckel’s work, see: Olaf Breidbach,

Ernst Haeckel. Bildwelten Der Natur. (Munich/Berlin/London/New York: Prestel, 2006), 187–94.

[24] For information on coral specimens in the Jena Phyletic Museum collected by Haeckel at the Red Sea coast, I thank the preparator Bernhard L. Bock, who also provided photographs.

[25] For this information I thank the curator of the marine invertebrates collection, Carsten Lüter, and the research assistant Fiona Möhrle for providing the exchange of letters.

[26] See: Susanne Köstering,

Natur Zum Anschauen: Das Naturkundemuseum Des Deutschen Kaiserreichs 1871-1914 (Cologne/Weimar/Vienna: Böhlau Verlag, 2003); And: Carsten Kretschmann,

Räume Öffnen Sich: Naturhistorische Museen Im Deutschland Des 19. Jahrhunderts (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 2006).

[27] See: Kretschmann,

Räume Öffnen Sich: Naturhistorische Museen Im Deutschland Des 19. Jahrhunderts, 92; Since the middle of the century aquariums and dioramas of watery environments became an attraction of many natural history museums and zoological gardens in the global North (and of wealthy homes in the case of the former) seeking to mimic the lively and colorful natural habitat of marine species and their ecology. See: Natascha Adamowsky,

The Mysterious Science of the Sea, 1775-1943 (Abingdon/New York: Routledge, 2016); And Endt-Jones,

Coral: Something Rich and Strange, 7–16.

[28] See, for instance: J.E.N. Veron,

Corals in Space and Time: Biogeography and Evolution of the Scleractinia. Ithaca; NY: Cornell University Press, 1995. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995); And Sean D. Connell and Gillanders Bronwyn, eds.,

Marine Ecology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), 328–49.

[29] See: Petra Löffler, ‘Colonizing the Ocean: Coral Reef Histories in the Anthropocene’, in

Earth and beyond in Tumultuous Times. A Critical Atlas of the Anthropocene, ed. Réka Patrícia Gál and Petra Löffler (Lüneburg: Meson Press, 2021), 185–213.

bibliography

Adamowsky, Natascha. The Mysterious Science of the Sea, 1775-1943. Abingdon/New York: Routledge, 2016.

Breidbach, Olaf. Ernst Haeckel. Bildwelten Der Natur. Munich/Berlin/London/New York: Prestel, 2006.

Connell, Sean D., and Gillanders Bronwyn, eds. Marine Ecology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Darwin, Charles. The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs: Being the First Part of the Geology of the Voyage of the Beagle (1832-1836). London: Smith, Elder & Co, 1842.

Daston, Lorraine, ed. Biographies of Scientific Objects. Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

Dunning, Hayley. ‘Charles Darwin’s Coral Conundrum’. Natural History Museum, 23 January 2023. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/charles-darwin-coral-conundrum.html.

Endt-Jones, Marion. Coral: Something Rich and Strange. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013.

Haeckel, Ernst. Arabische Korallen. Berlin: Verlag von G. Reimer, 1875.

———. Generelle Morphologie Der Organismen: Allgemeine Grundzüge Der Organischen Formenwissenschaft, Mechanisch Begründet Durch Die von Charles Darwin Reformirte Descendenztheorie. Vol. II: Allgemeine Entwickelungsgeschichte der Organismen. Verlag von G. Reimer, 1866.

Kopytoff, Igor. ‘The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process’. In The Social Life of Things. Commodities in Cultural Perspective, edited by Arjun Appadurai, 64–91. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Köstering, Susanne. Natur Zum Anschauen: Das Naturkundemuseum Des Deutschen Kaiserreichs 1871-1914. Cologne/Weimar/Vienna: Böhlau Verlag, 2003.

Kretschmann, Carsten. Räume Öffnen Sich: Naturhistorische Museen Im Deutschland Des 19. Jahrhunderts. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 2006.

Latour, Bruno. Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2017.

———. Pandora’s Hope: Essays in the Reality of Science Studies. Cambridge/London: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Livingstone, David. Putting Science in Place: Geographies of Scientific Knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Löffler, Petra. ‘Colonizing the Ocean: Coral Reef Histories in the Anthropocene’. In Earth and beyond in Tumultuous Times. A Critical Atlas of the Anthropocene, edited by Réka Patrícia Gál and Petra Löffler, 185–213. Lüneburg: Meson Press, 2021.

Mignolo, Walter D. The Darker Side of Western Modernity. Global Futures, Decolonial Options. Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2011.

Sponsel, Alistair. ‘From Cook to Cousteau: The Many Lives of Coral Reefs’. In Fluid Frontiers: New Currents in Marine Environmental History, edited by John R. Gillis and Franziska Torma, 137–61. Cambridge: The White Horse Press, 2015.

Thomas, Nicholas. Entangled Objects: Exchange, Material Culture, and Colonialism in the Pacific. Cambridge/London: Havard University Press, 1991.

Vennen, Mareiken. Das Aquarium: Praktiken, Techniken Und Medien Der Wissensproduktion (1840 – 1910). Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2018.

Veron, J.E.N. Corals in Space and Time: Biogeography and Evolution of the Scleractinia. Ithaca; NY: Cornell University Press, 1995. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995.

Walther, Johannes. Die Korallenriffe Der Sinaihalbinsel: Geologische Und Biologische Betrachtungen. Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1888.

citation information:

Continue Reading

With his 1873 journey, Haeckel explicitly followed in the footsteps of the natural scientist Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg, who had already travelled to the Red Sea in 1832 and had taken up quarters in El Tor to study coral species in their natural habitat.

With his 1873 journey, Haeckel explicitly followed in the footsteps of the natural scientist Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg, who had already travelled to the Red Sea in 1832 and had taken up quarters in El Tor to study coral species in their natural habitat.

Ayala Levin's master class (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger)

Ayala Levin's master class (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger) The gd:c summer school takes a field trip to the Museum Fünf Kontinente. (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger)

The gd:c summer school takes a field trip to the Museum Fünf Kontinente. (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger) One, yet many (but not too many). (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger - the author in the back left with the snappy Hawaiian shirt)

One, yet many (but not too many). (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger - the author in the back left with the snappy Hawaiian shirt)

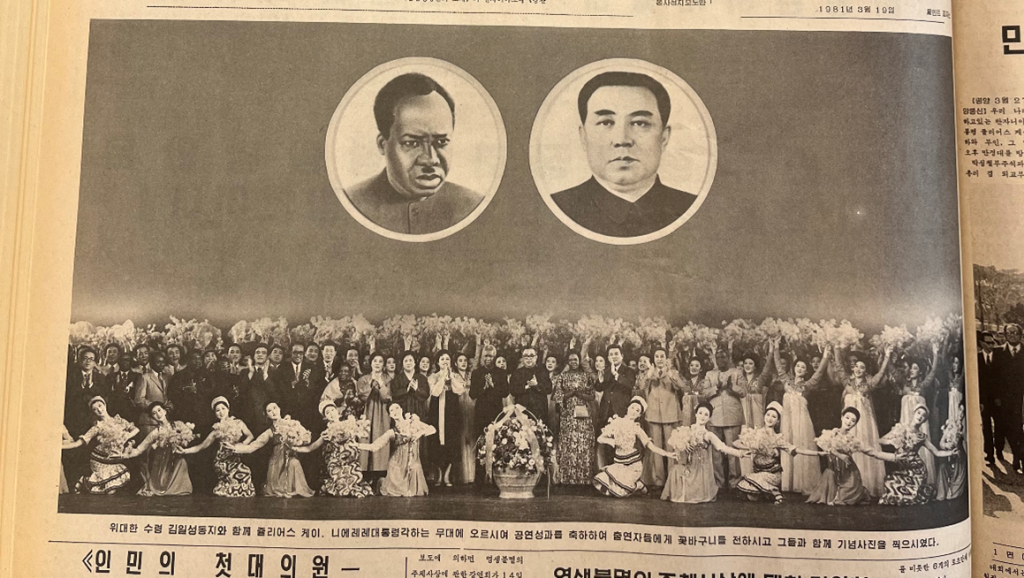

Julius Nyerere and Kim Il Sung congratulating the actors and actresses after watching a musical <Song of Paradise> in Mansudae Art Theater (Rodong Shinmun March 28, 1981), photograph by the author.

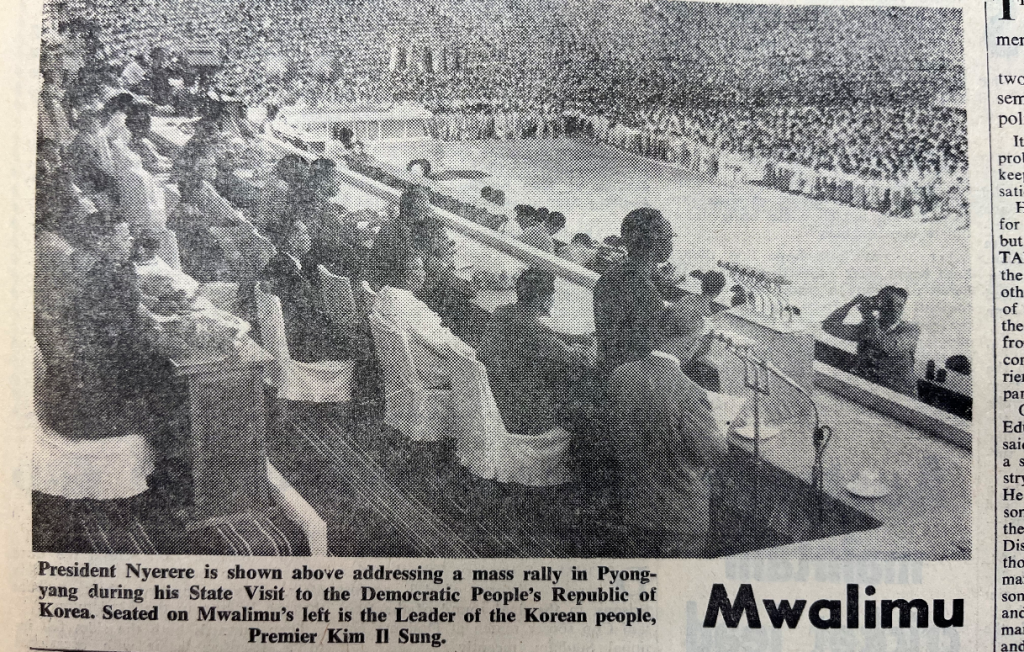

Julius Nyerere and Kim Il Sung congratulating the actors and actresses after watching a musical <Song of Paradise> in Mansudae Art Theater (Rodong Shinmun March 28, 1981), photograph by the author. Julius Nyerere addressing a speech in front of a mass rally in Pyongyang (The Nationalist, June 27, 1968), photograph by the author.

Julius Nyerere addressing a speech in front of a mass rally in Pyongyang (The Nationalist, June 27, 1968), photograph by the author.

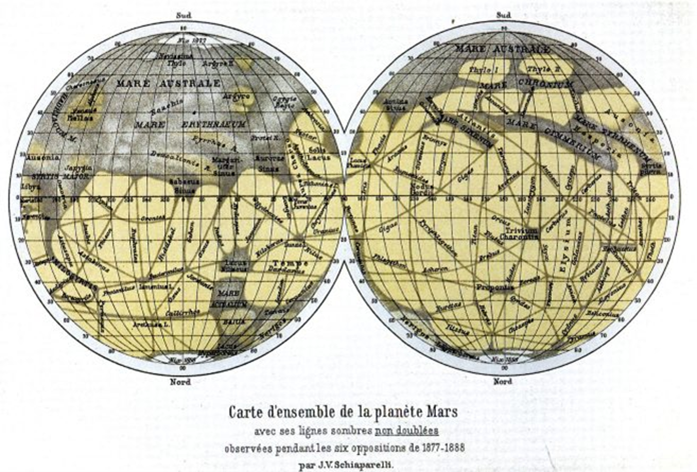

A depiction of the imagined system of canals on Mars. Title of Cosmopolitan Magazine XLIV, 4 (March 1908). https://www.loc.gov/item/cosmos000114.

This theory about life on Mars featured prominently in the discussion around 1900 about whether the new wireless communication technology could be used to communicate with extra-terrestrial beings — a discussion electrified by pioneers of that technology, like Nikola Tesla and Guglielmo Marconi, as well as the keen interest of the press. Already in 1892, Flammarion was convinced that the prospect of communicating with extra-terrestrials was ‘not at all absurd’.

A depiction of the imagined system of canals on Mars. Title of Cosmopolitan Magazine XLIV, 4 (March 1908). https://www.loc.gov/item/cosmos000114.

This theory about life on Mars featured prominently in the discussion around 1900 about whether the new wireless communication technology could be used to communicate with extra-terrestrial beings — a discussion electrified by pioneers of that technology, like Nikola Tesla and Guglielmo Marconi, as well as the keen interest of the press. Already in 1892, Flammarion was convinced that the prospect of communicating with extra-terrestrials was ‘not at all absurd’.