Dis:connected Cold Wars: rethinking the existence of a vanished state in global history

ann-sophie schoepfel

Stele commemorating Tran Van Ba in Liège (Image courtesy of the author)

On a springtime walk in one of the green parks in the Belgian city of Liège, I was astounded to discover a stele commemorating Vietnamese anti-communist Tran Van Ba. This memorial turned out to be the perfect embodiment of the aesthetics of Cold War omission. It piqued my curiosity. Liège, situated in the Meuse valley, is known as the former industrial backbone of Wallonia. What was a stele in memory Tran Van Ba doing here? Though I had originally planned to discover explore the industrial heritage of Liège and to visit the House of Metallurgy and Industry that day, I decided to go back to my hotel to learn more about Tran Van Ba instead.

On the way back to my hotel, I remembered the name Tran Van Ba as a whisper echoing from the chaos of French colonial archives in Aix-en-Provence. My small hotel room had a funky atmosphere, like a 1970s youth hostel. I turned my computer on. I felt like I was going to solve a mystery like Sherlock Holmes. Who was Tran Van Ba? Who had built this stele? Here Google would serve as Dr Watson, my loyal assistant.

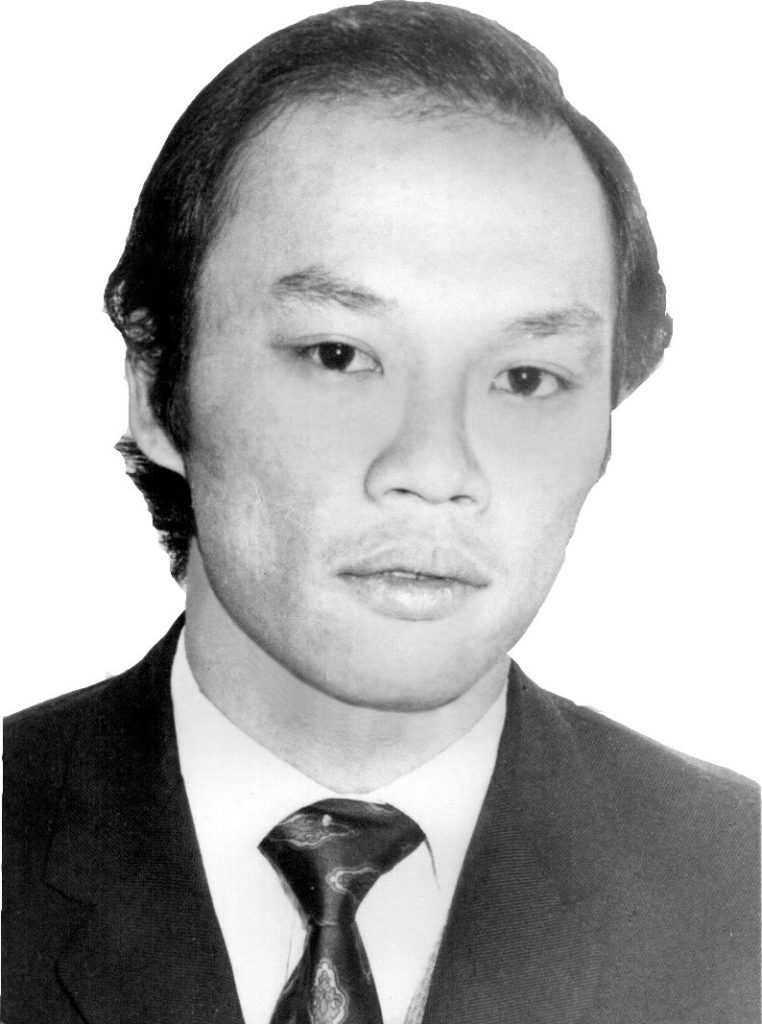

Tran Van Ba was a major figure of the Cold War, to whom Reagan awarded the Medal of Liberty. My preliminary investigation revealed that many Vietnamese in exile saw Ban as a martyr of the struggle against communism. On 8 January 1985, roughly a decade after the end of the American war in Vietnam, Tran Van Ba (1945-1985) was executed for high treason in Thu Duc, a municipality close to Ho Chi Minh City. It was an ignominious end to a life deeply marked by the violent upheaval Vietnam witnessed throughout the twentieth century.

Tran Van Ba, the gentleman (Image: agevp)

Here − in life and death − there is a strange symmetry. In 1966, Tran’s father, himself a prominent political figure with presidential ambitions, was assassinated in South Vietnam by the Viet Cong. Two decades earlier, in 1945, his uncle, the founder of the Vietnamese constitutional party, was shot by the Viet Minh. These symmetries condemned any possibility of moderation in a Vietnam torn between nationalism, communism and capitalism.

For North Vietnam, the fall of Saigon in April 1975 represented triumph in a decade-long war for national liberation against American imperialism. For Tran Van Ba, it was just the beginning of a new struggle that ended in Thu Duc, a struggle that persisted across three generations and permeated the lived experience of Tran Van Ba. It combined a series of disconnections − war, memory and diasporic battles over symbols of nationhood – and raged from Saigon to Paris, Bandung to the United Nations and from Little Saigon in California to Alt-Mariendorf in south Berlin. These disconnections resulted in the erection of the statue of Tran Van Ba in Liège.

In my small room, I decided to turn off my computer. I had to understand where the origins of these disconnections lay. I dived into the abyss. I thought about my scientific research on French colonial Indochina. Finally, I understood. These disconnections were dawning as French imperial sovereignty waned, when a sprawling empire, which dominated much of the Southeast Asian landmass and West Africa, disappeared in the aftermath of World War II. Decolonisation represented a disjuncture in Vietnamese history, symbolised by the death of Tran Van Ba’s uncle, Bui Quang Chieu (1973-1945), whom I had the chance to study during my doctoral research.

Bui Quang Chieu was a politician and a journalist in French Indochina. In 1917, he founded the journal La Tribune Indigène in Saigon. French Governor General Albert Sarraut supported him. Indeed, Bui Quang Chieu advocated the modernisation of Vietnam under French colonialisation, but the Vietnamese communist party did not accept his position. The Viet Minh considered him a collaborator. When Japan surrendered, the Viet Minh executed Bui Quang Chieu, his four sons and his daughter. Decolonisation entailed fratricidal struggle between the various Vietnamese nationalist movements.

France’s Afro-Asian empire did not evaporate into thin air. In the 1950s and 1960s, Vietnamese statesmen, commissions, committees and a bevy of soldiers and scoundrels descended on the waning French empire. They dissected, sorted and reorganised its parts into what we might call ‘ground zero’ for Cold War in Afro-Asia. It was unquestionably a foundational moment for a new post-imperial and international order.

On the turbulent frontiers of post-imperial Asia, the end of the First Indochina War between the Viet Minh and France was a messy process of redrawing collapsing boundaries. Populations displaced in wartime migrated. The new post-colonial states and societies were militarised in the Cold War. Diplomats from France, the Viet Minh, South Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, the Soviet Union, China, the USA and the UK sought agreement in Geneva from April to July 1954. The agreement they achieved temporarily separated Vietnam into two zones, a northern zone to be governed by the Viet Minh and a southern zone to be governed by the State of Vietnam, then headed by former emperor Bao Dai.

The disconnections at the end of the French colonial empire mentioned here had global impacts. They shaped not only the transformation of international relations in the Cold War; they also laid the ground for a transnational exiled network at the end of the American War in 1975.

It is at Bandung, Indonesia that the divisions between North and South Vietnam became glaring. The 1955 Bandung Conference is considered the birth of the Third World. As the Western empires slipped into crisis, anticolonial elites were fomenting a frenetic vision of how to reshape world affairs. For the Martinican poet Aimé Césaire, Bandung signified ‘to Europe that the time of the European empire was over’.[1] The French sociologist Raymond Aron was more critical: Bandung, although Afro-Asian, was very similar to a typical meeting of Western intellectuals and diplomats. He noted the same disproportion ‘between the pretensions of the men and the insignificance of the unanimous motions’ and ‘the same invocation of principles (fundamental human rights) by those who despise or violate them’.[2]

Neither Césaire nor Aaron saw Bandung as the birth of a divided nation − Vietnam. After nine years of war, North and South Vietnam were irreconcilable. Their delegations present at Bandung refused to meet. The Democratic Republic of Vietnam delegate Pham Van Dong addressed the conference by reiterating the commitment made in the 1954 Geneva Conference. The delegate of the State of Vietnam, Nguyen Van Thoai, cited the influx of North Vietnamese refugees in South Vietnam as the result of a ‘dictatorial regime’.[3] The two delegations had contradictory views on politics and nationhood.

After Bandung, North and South Vietnam became two pawns on the global chessboard, taking on Korea’s role of the hot front of the Cold War. North Vietnam was supported by China and the Soviet Union, the South by the United States. With the Vietnam War from 1955 to 1975, the term ‘Vietnam’ came to signify the transformation of modern war. It became central to the global countercultural movement, and it suffused debates on war, torture, colonialism, technology and media.

In the midst of that war, new global networks were created, networks that would come to be meaningful after the fall of Saigon in 1975. Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, became home of the monthly journal of the Asian Pacific League for Freedom and Democracy, The Free Front. This journal had a global audience in Australia, Japan, South Korea, France, Germany and the United States. From Paris, the former imperial metropole of French Indochina, Tran Van Ba led a student movement denouncing communism. In Western European cities, Vietnamese students demonstrated against communism and the American intervention in South Vietnam.

The United Nations became the diplomatic arena for North and South Vietnam. The two states both sought international recognition. In Europe and the United States, Vietnamese students appealed to the United Nations in their fight against communism. The Vietnamese Undersecretary Bui Diem attempted to secure UN support against North Vietnam. In October 1966, he visited the UN headquarters and met with UN Secretary General U Thant. However, his attempts and the students’ demonstrations were fruitless. Bui Diem, as South Vietnam’s ambassador to the United States, desperately attempted to secure $722 million USD in military aid to defend South Vietnam against the North in 1975.

Yet, with the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975, the state of South Vietnam was wiped from the map. Two years later, communist Vietnam was made an official member of the UN. Bui Diem became a refugee and university professor in the Unites States. For Tran Van Ba, the fall of Saigon was unacceptable. He decided to leave Paris, where he had studied political science, to engage in another, third war. His aim was to install an anti-communist government in Vietnam. In the process of deimperialisation, the disconnections in the Vietnamese nation became striking.

What a difference a uniform makes. (Image: indomemoires)

The disconnections in the history of Vietnam during the Cold War became visible in societies at the end of the Cold War. The fall of Saigon catalysed the mass exodus of Vietnamese ‘boat people’. Transnational exile networks grew throughout the worldwide diaspora. They built upon the pre-existing Vietnamese students’ and anti-communist networks that had emerged in Western Europe, the United States and Australia.

These disconnections transformed the political, social and visual landscapes of the cities where the boat people lived in exile. For them, the flag of South Vietnam became the symbol of freedom from North Vietnam. It consists of a yellow background, symbolising the Empire of Vietnam, with three red horizontal stripes through the middle, emblematic of the common blood running through North, Central, and South Vietnam. In Alt-Mariendorf in south Berlin, Hannover, Hamburg and Stuttgart, this flag is displayed during the Vietnamese communities’ gatherings to call for democracy in a unified Vietnam.

On 21 October 1990, in the United States, former soldiers and refugees from the former South Vietnamese regime founded the Provisional National Government of Vietnam, headquartered in Orange County and Little Saigon. Dao Minh Quan was elected as the president of the newly created ‘Third Republic of Vietnam’. US government staff gave speeches and expressed hope that the newly elected president would work closely with the USA. Yet, for many exiled Vietnamese, Dao Minh Quan did not have any political legitimacy. He was only interested in embezzling from the provisional government.

In Europe, Vietnamese diasporas are still fighting against the communist Vietnamese regime. They consider the current regime ‘authoritarian and corrupt’. They denounce human rights abuses in Vietnam. In parallel with this political struggle, the exiled Vietnamese communities are committed to building sites of memory. In Hamburg, Liège and Geneva, members of the Vietnamese diaspora have contacted municipal authorities to install steles commemorating the boat people.

The mayor of Paris first agreed to the installation of a plaque in memory of Tran Van Ba in the 13th arrondissement in 2008. The Vietnamese embassy protested to French authorities, who eventually renounced the plaque. In Liège, a statue honouring Tran Van Ba was erected on 30 June 2006. Local and Belgian national newspapers, such as Le Soir, La Libre Belgique and La Meuse published articles on Tran Van Ba as well as on the boat people at that time. Every year, on 8 January, the Vietnamese exiled community in Liège pays respect to Tran Van Ba, a ‘martyr of communism’.

The Vietnamese government considers these commemorations problematic. It listed the Provisional National Government of Vietnam as a terrorist organisation and condemns the efforts of the Vietnamese diaspora to overthrow the current regime. It is said that the Cold War ended with the fall of the Berlin Wall. In fact, it continues in the streets and the squares of Liège, Berlin, Paris, Orange County and Little Saigon.

In my small room in Liège, I was reflecting on my own investigations. To no one’s surprise, Google is a wonderful fount of information. I never regretted not visiting the House of Metallurgy and Industry in Liège and or skipping my exploration of its industrial heritage. I thought to myself how a series of disconnections resulted in the creation of a statue in a Belgian city, and how the complexities of global disconnections have transformed our societies.

[1] Statement at the meeting of 27 January 1956 organised by the Comité d’Action des intellectuels contre la poursuite de la guerre en Afrique du Nord.

[2] Raymond Aron, ‘Bandoeng: Conférence de l’équivoque’, Le Figaro, 27 April 1955, 1.

[3] ‘Konferentsiia Stran Azii i Afriki Zakonchila Svoiu Rabotu’, Pravda, 25 April 1955, 4.

[4] Interviews of members of the Vietnamese diaspora in Berlin in November 2021.

bibliography

Aron, Raymond. ‘Bandoeng: Conférence de l’équivoque’. Le Figaro. 27 April 1955.

Pravda. ‘Konferentsiia Stran Azii i Afriki Zakonchila Svoiu Rabotu’. 25 April 1955.

citation information

Schöpfel, Ann-Sophie. ‘Dis:Connected Cold Wars: Rethinking the Existence of a Vanished State in Global History’. Institute Website. Blog, Global Dis:Connect (blog), 19 July 2022. https://www.globaldisconnect.org/07/19/disconnected-cold-wars-rethinking-the-existence-of-a-vanished-state-in-global-history/?lang=en.