In

Blog 2023

felix ehlers

Slow time can lead to more meaningful work

– Ananya Mishra, workshop attendee

Global dis:connect was honoured to host

Ecology, aesthetics and everyday cultures of modernity, a fascinating workshop held on 10-11 July 2023 and conceived by our fellow Siddharth Pandey. The event brought together scholars from various fields to discuss linkages between ecology, everydayness and aesthetics by looking at the modern period from the 19th century to the present. The participants shed light on several topics related to aesthetics by looking at art — movies, paintings and literature — that confront humanities’ relationship with the environment.

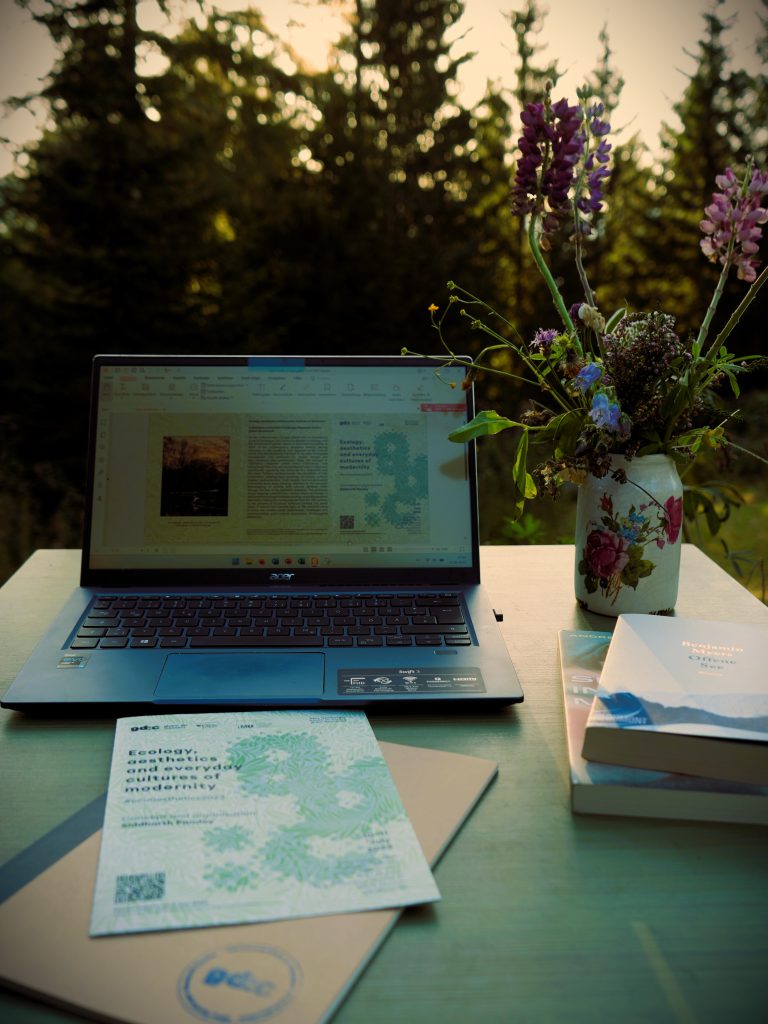

The sound of crickets chirping fills the air, which is heavy with the smell of freshly mowed grass and smoke from burning larch. I inhale the air and look over my laptop into green trees, moving in the wind of an approaching thunderstorm that’s already rumbling among the mountains. It’s a picturesque setting, inspiring surroundings for writing, reading and thinking. It is an aesthetic environment, a place that clearly collapses the illusory dichotomy between nature and culture. Somewhere in the Austrian mountains I can to write about culture in nature, and I do so using cultural practices and materials in an environment that feels wild and untouched but is designed by humans. This aesthetic place is the Anthropocene in microcosm, perfectly suited to write this reflection.

Where does nature begin and culture end? (Photo by the author)

The word

Anthropocene, like the geological epoch, is charging ahead, having become a buzzword evoking dystopian images of environmental degradation, global human-caused pollution and mega-cities expanding in formerly wild environments. The world in the Anthropocene isn´t aesthetic, but what counts as aesthetic changes. Most people would consider winter in general and especially snow in the Alps beautiful, but prior to the rise of tourism and winter sports in the second half of the 19th century, winter in the mountains signified danger and death, not beauty and joy.

[1]

What is aesthetic? Siddharth Pandey claims reception through our physical senses provides the best access to the concept of aesthetics, which was later connected with evolving conceptions of beauty. Today, aesthetic and beautiful are practically synonyms. When reflecting on aesthetics, one starts see them everywhere — our aesthetic environment, the beautiful library of on the ground floor of our gd:c building, the alpine setting where I wrote this article. Aesthetics influence our thinking and our work as researchers.

Even so, the Anthropocene was indelibly inscribed in the workshop’s topic and influenced the discussions of artworks showcasing the interplay between humans and the environment. But aesthetics offered an alternative to the stereotypically dystopian view of the Anthropocene. We noticed this already in the early stages of preparing the workshop when Siddharth Pandey, Daniel Bucher (another student assistant) and I met for the first time to discuss how to design the posters and flyers.

The first drafts visualised a dystopic environment, but Siddharth Pandey wanted to reconceive the design. Using motifs by the British craftsperson, polymath and founder of the Arts and Crafts movement, William Morris, we combined the ideas of everyday culture, aesthetics and the intertwining of nature and culture.

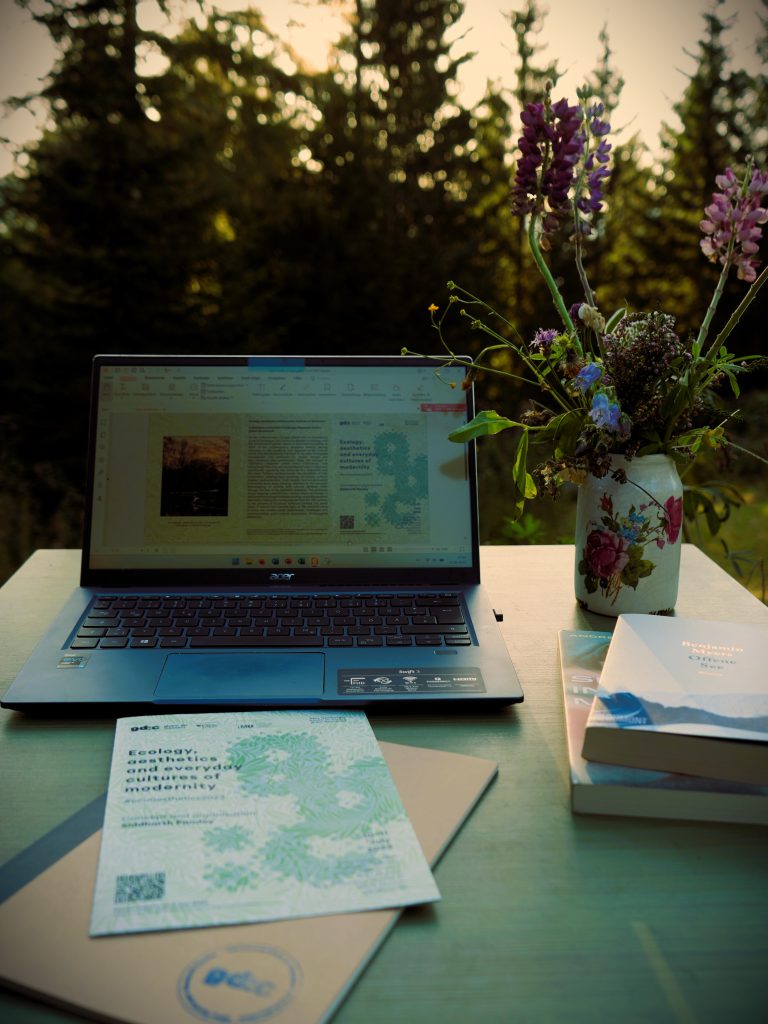

On two scorching days in July, the participants gathered in the gd:c library, where we discussed many topics. We listened to Salu Majhi’s poetry, saw photographs of sled dogs towing a sled through a shallow, crystal-blue lake on still-frozen sea ice, recalled our childhood memories with an analysis of the visual language

Bambi, learned about Chile saltpetre in artworks and as a medium, virtually visited the

Time Landscape project in lower Manhattan, and more.

The presenter's view of the library (Photo by Siddharth Pandey)

As a historian, I was unfamiliar with art historians’ and literary critics’ approaches, but all the panels were inspiring despite (or because of) that, relating easily to my own field and interests. Each presentation touched aspects of everyday life in some way. Our reliance on synthetic fertilisers to produce food, firsthand experiences of the effects of climate change and a childhood encounter with Caspar David Friedrich’s romantic paintings are just some examples.

The workshop opened with David Whitley´s keynote on how the textual descriptions in the 1928 novel

Bambi. A Life in the Woods by the hunter Felix Salten had been translated into visual forms in Disney´s

Bambi movie. His analysis of a movie most of us recall from our childhood was fascinating, because the visual language is typically absorbed unconsciously. Whitely’s exposition of such aesthetic commonplaces set the tone for the following presentations.

In the first panel on the language of plants, Sarah Moore spoke about Alan Sonfist’s

Time Landscape project, in which he and the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation represented the ecological loss in Manhattan over the last 400 years with a slow-growing forest on a quarter-acre of land that was no longer maintained as a park. Moore connected this project with works of the 19th century that were already dealing with human-induced environmental degradation, like Thomas Cole’s works and contemporary seed banks. Moore presented

Time Landscape as a place where trees bring us a message from the past, a message that recurred in other presentations.

Next, Vera-Simone Schulz discussed images of plants, analysed how ecology and aesthetics influence these depictions, and why depictions of tropical plants can be intentionally misleading. The floral decorations at lunch were a glaring coincidence.

Geopolitical aesthetics were the topic of the second panel treating mineral resources, their exploitation and related artworks. Nicolas Holt’s presentation focused on minerals, especially Chilean saltpetre, a powerful natural fertiliser that is less harmful than synthetic fertilisers gained by the Haber-Bosch-Method, as a medium in art history.

The next presentation by Ananya Mishra focused on the translation Salu Majhi’s songs and analysed how local forms of protest against mining companies are expressed in his poetry, showing that Majhi considered his poetry as a form of protest as well as part of his everyday life. Beyond the topic itself, Mishra’s multidimensional presentation was intriguing. Not only did she show and discuss translations of the poems on a screen, she combined this with audio recordings of Salu Majhi singing the poems as ambient sound. Together with a video of her journey to Salu Majhi documenting her research, this blended the object of research, the act of research, the past, the present and the presentation.

Hence we return to the quote opens starts this report. ‘Slow time leads to more meaningful work’. This is a concept I cherish in my own work: not working slowly in terms of pace and productivity, but taking and investing time for the best possible, most meaningful result is valuable and necessary.

Of form and feeling was the topic of the third panel. Nathalie Kerschen opened the panel with her talk on expressing nature in architectural design and how the experience of nature, termed

eco-phenomenology, influences design. She also touched on the importance for scholars not to lose their connection with everyday experiences. Touch grass.

Following up was Jane Boddy with her presentation on form-feeling and the aesthetics of nature around 1900. She asked whether form-feeling was a general collective experience and about the role of nature in that experience. Boddy demonstrated the importance of looking at feelings and emotions. In her words ‘the feeling of a form (

Formgefühl) is source and intuition of style’.

The last panel on the first day was titled

Between the known and unknown and dealt with experimental prehistory and Bermuda oceanographic expeditions. Jutta Teutenberg started her talk about experimental prehistoric research with a focus on recreating the conditions under which prehistoric artists created art and crafts by referring to the ethnographer Frank Hamilton. This again invoked positionality and the importance of considering feelings, as an experimental prehistoric researcher who feels like an artist will experience different things and produce different results than a researcher who does not.

[2]

Magdalena Grüner analysed three of Else Bostelmann’s 1934 paintings capturing fishes with watercolours as seen by oceanographic expeditions to Bermuda in their natural environment and by taking into account how the colour spectrum changed with the depth. She used taxidermically stuffed animals as models and descriptions by the deep-sea researcher William Beebe because Bostelmann hadn’t ever seen the real thing. Bostelmann therefore worked with her imagination and artistic methods, diverging from the aim of the expedition, which was to gain scientific knowledge.

The fifth panel, titled

The limits and edges of perception, opened with Jessie Alperin’s presentation about the imagination of the Earth from above in Odilon Redon’s

Le paravent rouge, a folding screen made for André Bonger. She analysed this artwork as an everyday, aesthetic object, which made it possible to view the impossible: the Earth imagined from above visualised inside a home.

The sixth panel on the prism of the pastoral began with Mihir Kumar Jha, who talked about spatialisation in colonial literature and the pastoral as a genre that deals with man’s interaction with nature. He analysed the pastoral landscape with a view to the surroundings of Hazaribagh as an ecological space between wilderness and civilisation, between nature and culture.

From the pastoral in colonial literature, we moved to the pastoral in paintings by the Belgian artist Roger Raveel and his attempts to develop an aesthetics of complexity, as presented by Senne Schraeyen’s. This talk also focused on the nature-culture nexus and how the environment changed through the rapid economic change in the second half of the 20th century. Recalling how the Alps also changed radically in the last century and the ensuing sense of ecological loss, I felt compelled to ask whether the loss and damage, the pollution and the destruction are necessary to prompt new aesthetic perceptions of formerly inaccessible landscapes and our environment in general.

The final panel was titled

Ice tales and offered a stark contrast to the 34-degree temperatures that afternoon. Oliver Aas opened the last panel on the Artic Sea ice by analysing art that depicts melting sea ice and questioning how our view of the Artic changes in light of the effects of climate change.

From the ice of the present, we moved to Kaila Howell’s close reading of Caspar David Friedrich’s

The Sea of Ice and its historic depiction of ice of the past. She combined her analysis of the painting with Kant’s philosophy and the concept of scale in art history.

After seven closely connected and very diverse panels with fascinating and inspiring presentations and discussions, Camille Serchuk’s concluding remarks were the grand finale. Serchuk wonderfully summarised the diverse presentations and related them to her own work on medieval maps, which demonstrated the relevance of the topic beyond its chosen modern period. Still, the end had to be aesthetic. Therefore, we enjoyed a walking tour through the English Garden in the sweltering heat, but it made for a perfectly aesthetic ending thanks to a field of wild flowers, a part of the English Garden uncultivated and untouched by landscapers, bringing us back full circle to the

Time Landscape project.

Reflectively synthesising nature, culture and aesthetics

The workshop is over, but the associations and threads it spun continue.

Holt’s paper, for example, evoked the relevance of mineral resources in the context of digitalisation, especially with regard to the humanities. Mineral resources make our daily life possible, though we take them for granted. Digitalisation, which is as indomitable as it is universal, also shapes our research practices and relies heavily on mineral resources. This text, for instance, was written on a laptop produced in Taiwan with mineral resources from China and Latin America, and I also use it to read digital papers by scholars from the Netherlands, the USA and India.

The more we digitalise, the more we lose a genuine connection to our analogue environment. But ironically, that same digitalisation and environmental alienation coincides with greater environmental exploitation. Materials are a medium by which we surpass our natural boundaries and enter a digital space. We do well to remember, however, that this journey is predicated on natural resources. The virtuality of digitalization is an illusion. In the end, everything is analogue.

Many of the presentations, especially those from Boddy, Grüner, Mishra and Moore highlighted the importance of reflecting on emotions in research. Art is emotion; it is, to paraphrase Benjamin Myers, the desire to cast the moment in amber.

[3] Seeing Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings, hearing Salu Majhi’s songs, smelling the plants growing in the

Time Landscape project makes us

feel. Those feelings can be shared or disparate, again depending on our mindsets, experiences and many other factors. If a good poem breaks open the oyster shell of the mind to reveal the pearl within, as Benjamin Myers writes,

[4] then art in general can have the same, if not a much more intrusive effect. This must be especially true for art that confronts humans’ impact on the environment, the nature—culture interaction and everyday life.

In research as in life, we work with narratives, and our preconceptions, beliefs, values and feelings affect those narratives.

[5] To observe and note the influence of our feelings as agents in the past and the present in producing and distributing knowledge is sensible for various reasons, but especially for art and aesthetics. The concept of aesthetics relies on our senses, which combine with and shape our feelings and emotions.

Jha’s reflections prompted me to reconsider the landscape I feel close to, as he described a place totally different but then again very similar to the place in the southern Alps that inspired me and where I wrote these words. A landscape that seems wild, inhabited by wild fauna with wolves returning, but shaped by grazing cows, ruminating sheep and humans cutting trees and building ski slopes on which deer — animals designed to live in open spaces — spend the dawn reintroduces questions of perception and emotions. Would the Alps be perceived as beautiful were they wild rather than cultivated? Sharing these forests and mountain ridges with wolves, after their local extinction centuries ago, is changing my feelings for this region, but I’m not yet sure how. Perhaps the landscape will now feel wilder, and it would be more romantic if the call of the rutting deer mixes with the howling of a wolf. But even if they pose no threat to me, their effects on grazing livestock – possibly fatal – and measures to protect them, like herding dogs, will likely lead to a loss of human freedom and carefreeness.

Superficially, we learned a lot about works of art treating and confronting humans’ impact on nature, a lot about art historical views on everydayness and ecology. Underneath that surface, though, the workshop raised far more questions, some of which I have raised here. Despite their apparent disconnection, when seen from above these questions might reconnect many things, including us as feeling, emotional beings, dependent on but alienated from our environment.

[1] For further information, see Andrew Denning,

Skiing into Modernity: A Cultural and Environmental History (Oakland: University of California Press, 2014).

[2] For further information on the effect of emotions in research, see Ute Frevert,

Gefühle in der Geschichte (Göttingen: Vendenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2021).

[3] Benjamin Myers,

Offene See (Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, 2020), 14.

[4] Myers, Offene See, 2022, 111.

[5] For further thoughts on how we shape our narratives, see Douglas Booth, "Seven (1+6) surfing stories: the practice of authoring,"

Rethinking History: The Journal of Theory and Practice 16, no. 4 (2012),

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13642529.2012.697284.

Bibliography

Booth, Douglas. "Seven (1+6) Surfing Stories: The Practice of Authoring."

Rethinking History: The Journal of Theory and Practice 16, no. 4 (2012): 565-85.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13642529.2012.697284.

Denning, Andrew.

Skiing into Modernity: A Cultural and Environmental History. Oakland: University of California Press, 2014.

Frevert, Ute.

Gefühle in Der Geschichte. Göttingen: Vendenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2021.

Myers, Benjamin.

Offene See. Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, 2020.

citation information

Ehlers, Felix, 'Finding aesthetics everywhere: recalling a workshop on ecology, aesthetics and everyday cultures of modernity " Ben Kamis ed. global dis:connect blog. Käte Hamburger Research Centre global dis:connect, 17 October 2023, 2023, https://www.globaldisconnect.org/10/17/finding-aesthetics-everywhere-recalling-a-workshop-on-ecology-aesthetics-and-everyday-cultures-of-modernity/.

Continue Reading

Holt’s paper, for example, evoked the relevance of mineral resources in the context of digitalisation, especially with regard to the humanities. Mineral resources make our daily life possible, though we take them for granted. Digitalisation, which is as indomitable as it is universal, also shapes our research practices and relies heavily on mineral resources. This text, for instance, was written on a laptop produced in Taiwan with mineral resources from China and Latin America, and I also use it to read digital papers by scholars from the Netherlands, the USA and India.

The more we digitalise, the more we lose a genuine connection to our analogue environment. But ironically, that same digitalisation and environmental alienation coincides with greater environmental exploitation. Materials are a medium by which we surpass our natural boundaries and enter a digital space. We do well to remember, however, that this journey is predicated on natural resources. The virtuality of digitalization is an illusion. In the end, everything is analogue.

Many of the presentations, especially those from Boddy, Grüner, Mishra and Moore highlighted the importance of reflecting on emotions in research. Art is emotion; it is, to paraphrase Benjamin Myers, the desire to cast the moment in amber.

Holt’s paper, for example, evoked the relevance of mineral resources in the context of digitalisation, especially with regard to the humanities. Mineral resources make our daily life possible, though we take them for granted. Digitalisation, which is as indomitable as it is universal, also shapes our research practices and relies heavily on mineral resources. This text, for instance, was written on a laptop produced in Taiwan with mineral resources from China and Latin America, and I also use it to read digital papers by scholars from the Netherlands, the USA and India.

The more we digitalise, the more we lose a genuine connection to our analogue environment. But ironically, that same digitalisation and environmental alienation coincides with greater environmental exploitation. Materials are a medium by which we surpass our natural boundaries and enter a digital space. We do well to remember, however, that this journey is predicated on natural resources. The virtuality of digitalization is an illusion. In the end, everything is analogue.

Many of the presentations, especially those from Boddy, Grüner, Mishra and Moore highlighted the importance of reflecting on emotions in research. Art is emotion; it is, to paraphrase Benjamin Myers, the desire to cast the moment in amber.

Image: Ben Kamis

Image: Ben Kamis The global dis:connect team.

The global dis:connect team.