Bridging a gap: global knowledge production and its dis:connectivity — a review of the gd:c annual conference 2023

doğukan akbaş & peter seeland

Munich, 11-13 October 2023

The writer Bernadette Mayer addresses the plurality of knowledge production by interweaving various novellas in her work Story (1968). ‘All stories are at least not the same’, she says. How can this plurality be grasped and explored? How does knowledge get transmitted and applied, and what (global) dynamics apply? Last year’s annual conference, organized by Nikolai Brandes and Burcu Doğramaci of the Käte Hamburger Research Centre global dis:connect (gd:c), aimed to answer these questions. Combining notions of connectivity and disconnectivity in globalisation processes, the participants considered dis:connectivities in global knowledge production. Focusing on various forms of interruptions, absences, and detours in knowledge production, they sought a nuanced image to surpass the narrative of linear, boundless, uniform globalisation. The conference built on the previous year’s method-oriented conference.[1] And by inviting artists and activists in addition to scholars, gd:c emphasised diversity and multidisciplinarity in knowledge production. The annual conference covered three themes: exploration, carriers, and challenges of knowledge and its production. A film screening and museum visits took the participants out of the conference room and stimulated them with exploratory media.

Fig. 1: Starting point: Zu den Kinos — to the screening rooms. Image by: Doğukan Akbaş

The conference kicked off with a screening of the film Queer Gardening (2022). In this documentary, the urban planner, filmmaker and gardener Ella von der Haide (Munich) captures stories of queer individuals living in the USA through their individual experiences with gardening. The subjects expressed their resistance to the normative practice of gardening and the associated discrimination, which have traditionally been shaped by hetero-cis bias, through linguistic, etymological, spiritual and historical exploration of gardening. To rethink gardening from queer perspectives, not only in terms of societal norms but also as growing food and herbal medicines, was the primary goal of the documentary. Ecological knowledge, previously dominated by a heteronormative understanding of reproduction, can be reinterpreted and revised. Gardening can thus reflect queer identities as it creates and conveys queer knowledge.

The exiled writer and gender researcher Stella Nyanzi (Berlin) described challenges of queer knowledge production and started by defining herself as a knowledge producer. She emphasised her three identities, academic, poet and activist. Using visual activism, she focused on the criminalisation of knowledge production in Uganda and the resulting challenges of queer knowledge production. Uganda’s anti-homosexual laws subject queer people to defamation by the press and (physical) violence by the public, robbing them of their senses of safety and dignity. Nyanzi, without seeking a conclusion, sought to prompt future research and activism with a few questions: how can knowledge producers deal with such challenges, and how can queer knowledge contribute to society as a whole? The historian Stephanie Zloch (Dresden) sees education as a central pillar of knowledge production and addressed the challenges associated with (global) migration, particularly focusing on the educational circumstances in Germany during the major migrations since 1945. She examined displaced persons, the post-war education system, language schools for migrants, Islamic education in Germany and ‘foreigner classes’ in German schools. Zloch investigated how knowledge can be recontextualised and synthesised into new forms through interruptions and detours, political debates and national interests.

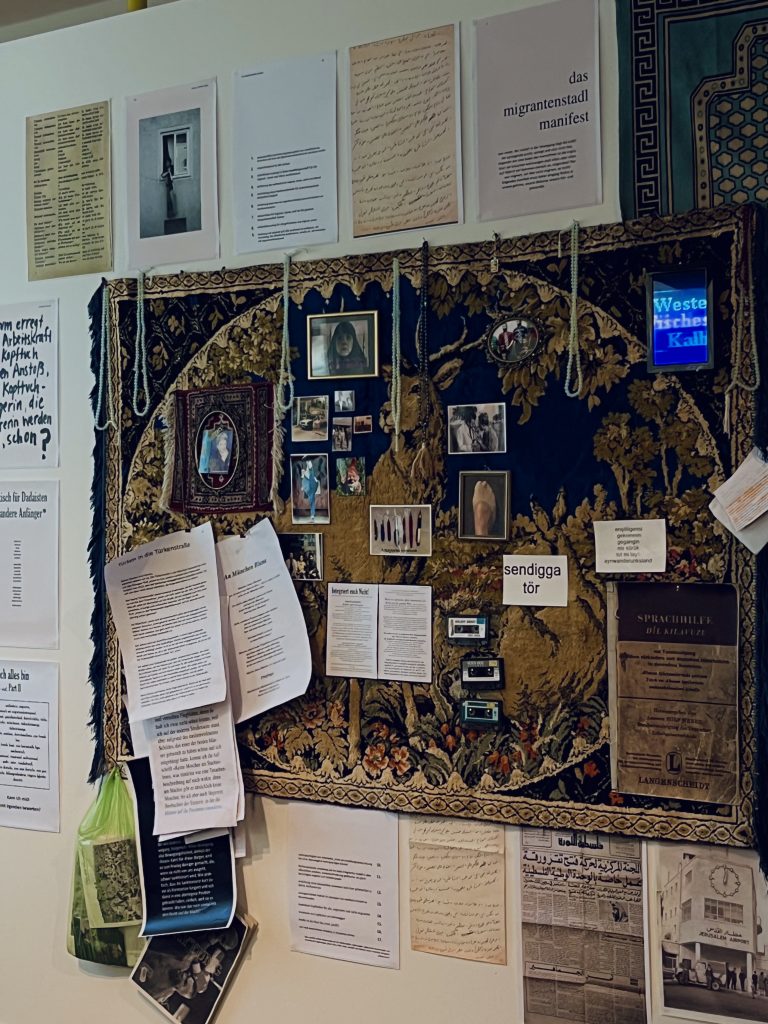

From the labour migrants of the 19th and 20th centuries to the present day, Munich has long been a city of migration, as illustrated by a guided tour of the Münchener Stadtmuseum led by historian Simon Goeke (Munich). The sociologist and artist Tunay Önder, for example, created a mind map of migration experiences with her Transtopischer Teppich (2016).[2] The collaged objects blend migration culture, forming hybrids of German and Turkish languages and memory cultures, resulting in the emergence of terms such as Migrantenstadl (migrant town) and even a whole migration dictionary. Culture and knowledge change through migration and give rise to completely new forms.

Fig. 2: Transtopischer Teppich. Image by: Doğukan Akbaş

The historian Lucie Mbignie Nankena (Dschang) discussed intergenerational and global transfer of knowledge, using the example of traditional Cameroonian dances. A dance can embody knowledge and convey identity as well as cultural and factual knowledge, about life with nature and traditions.

Mariana Sadovska (Cologne) concluded the day with her concert-lecture on this idea of knowledge transfer through culture and tradition. With her research-based collection of folk songs from Ukraine, Sadovska helps preserve and transmit oral culture. Her concert, explicitly scheduled as part of the lecture section and not as a marginal event, guided the audience through the multicultural musical landscape of Ukraine, using her voice and harmonium. This landscape includes Jewish, Albanian, Greek and Swedish influences. The mostly polyphonic pieces metaphorically represent the diverse Ukrainian culture. The ongoing war lent Sadovska’s connection of art and research particular relevance. Preserving and reviving knowledge through personal appropriation is her main goal.

The artist Lizza May David (Berlin) reported on her archive project in which she explores Philippine colonial history through photography. Western colonial powers created photo archives that only depicted their ideas and fantasies. Once these Western ideas had reached the Philippines, manifested in the photos and returned to Europe, David worked with them and sent her work back to Indonesia. This practice highlighted the global and dis:connective aspects of knowledge dynamics.

With her Urban Bodies projects the choreographer Yolanda Gutiérrez (Hamburg) connected to the theme of archiving. These projects are ‘colonial city tours’, in which choreographic performances, executed by David Valencia and Jana Baldovino, draw attention to the presence of colonisation in European cities and shape a decolonised future through dance. The body serves as a carrier of colonial experience, and the corporeality facilitates the production and transmission of knowledge about colonial history. Thus, she perceives the body as an archive of knowledge.

The writer Franz Dobler (Augsburg) guided the participants through the Archiv 451 exhibition at the Haus der Kunst. The autonomous publishing archive is the knowledge repository of the Trikont publishing house, which played a central role in Munich’s 1968 protests. As one of the first autonomous publishers in West Germany, it disseminated alternative perspectives on new social and ecological ideas in line with workers’ movements according to Franz Dobler, who himself participated as a writer and activist in the later years of the publishing house. With its focus on decolonisation and anti-fascism, the publisher shaped knowledge on a societal level. The archive exhibited not only published books but also records and documents from the music label and publishing house.

The art historian Mona Schieren (Bremen) considered the physicality of knowledge through the Brazilian artist Lygia Clark’s understanding of the body. In her project Structuring the Self (1988-89), Clark attempted to trigger memories in various people through physical touch and objects. She associates remembering, reviving and expanding knowledge with a transcendental physical knowledge experience. This means not only reading, learning and familiarising oneself with knowledge, but also physically experiencing and expanding it.

The corporeality of knowledge is palpable in Non Aligned Movement (2020) – a performance by artist Christian Guerematchi. A black man with a black mask, who donned the airs and uniform of the Yugoslav president Josip Tito before divesting them through dance.[3] The art historian Jasmina Tumbas (Buffalo) interpreted this performance as an Afro-European search for identity: the artist, originally from the former Yugoslavia, deconstructs Tito as a symbol of a racist, patriarchal and heteronormative society through his dancing body. Corporeality as a bearer and producer of knowledge can disrupt and reshape paradigms.

Ana Druwe (São Paulo) spoke on the institutional preservation and production of knowledge at the Casa do Povo cultural centre in São Paulo. Founded in 1946 by Jewish immigrants as a Holocaust memorial, Casa do Povo is a living monument, providing space for education, art, collective and social activities. Its diverse practices, fundamental openness and Nossa Voz – the in-house magazine – foster anti-fascism, intercultural dialogue and social understanding. ‘Sharing the key to the building’ is the motto signifying the trust and spirit of collaborative knowledge production among the house users.

The architect, theorist and activist Niloufar Tajeri (Berlin) also focused on buildings and the problems of architectural knowledge. Architecture directly and indirectly manifests various levels of knowledge in built space. So, who sees what in architecture, and how does it affect those who dwell therein? Using the example of current plans for Hermannplatz in Berlin, she revealed racist structures, potential exclusion and the importance of individual experience in architecture. Knowledge production does not end with construction — users and residents create knowledge within and with it. Architecture is an archive of knowledge that must become more aware of the challenge of including the people touched, affected and affiliated by and with it. ‘At least everybody doesn’t see the same in architecture’, concludes Tajeri fittingly.

A poster session, organised by Doğukan Akbaş, Sophia Fischer and Peter Seeland, catalysed dialogue with young scholars. Chiara Di Carlo (Rome) spoke about pilgrimages to the Holy Land in the 16th century and dis:connectivities in transmitting knowledge (see her article in this issue). Yunting Xie (Uppsala) and Jie Yang (Munich) presented their research on global knowledge transfer in 20th-century China. Sabrina Herrmann (Kassel) discussed contemporary artistic attempts to resist gender-based human rights violations, examining how Mexican and Colombian artists raise awareness. Scott Blum-Woodland (Cambridge) treated the reception of Russian post-war literature in the UK in the late-20th century. Blum-Woodland forwarded the thesis that knowledge production is inevitably local and depends on societal (and national) connections.

Fig. 3: The poster session team in the gd:c library. Image by: Doğukan Akbaş

The conference evinced a diverse, transdisciplinary and multi-perspective approach to knowledge production, without neglecting the common theme. Instantiating ‘glocalisation’,[4] we explored the global through local Munich. This conference fostered communication between the arts and sciences. Thus, it became a site of knowledge production itself. In lieu of a closing statement with concrete results, we proposed research questions, approaches, methods and topics for ongoing conversations. In a way, the conference concluded as it began, recalling the introductory quote by Bernadette Mayer: ‘knowledge is never the same’. The conference pointed to a gap in the current academic discourse. Knowledge and its production must be analysed more intensively, more broadly and more inclusively. And dealing with this fact is a challenge that research must necessarily face.

Fig. 4: Happy and fulfilled: celebrating the conference in the gd:c gardens. Image by: Doğukan Akbaş

(Global) knowledge production initially appeared to be an omnipresent concept in everyday life. We have all undergone an educational journey through school, university, work and our private lives, experiencing knowledge production first-hand. The term knowledge production immediately made us think of these institutional instances. While aware of significant differences on a(n) (inter)national level, awareness for the depth of these differences and the challenges evoked was not fully there. A mere glance at the conference programme showed that there is more to look at than just institutions. It provided us with a different approach to knowledge production and its underlying principles. A more out-of-the-box approach was necessary. It quickly became clear that this examination could only be successful from various perspectives across diverse disciplines, not limited to a lecture-type of examination. Historical assessments, musical performances and architectural considerations – all contributed to our awareness of the challenges of knowledge production and led to the outcome of our conference. We were especially impressed by the interdisciplinary collaboration of international researchers, ranging from facing political persecution for their research and the standing-up-for-justice we take for granted, to traveling through various regions experiencing war. It was their perspectives and personal stories that brought life to this conference.

[1] Peter Seeland, ‘Looking back on global dis:connect’s first annual conference: dis:connectivity in processes of globalisation: theories, methodologies, explorations’, static: thoughts and research from global dis:connect 2, no. 1 (2023), https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5282/static/41.

[2] Tunay Önder, Transtropischer Teppich, 2016, Carpet, paper, plastic, metal, digital material, 250 x 350 x 10 cm, Münchner Stadtmuseum, Sammlung Stadtkultur. https://sammlungonline.muenchner-stadtmuseum.de/objekt/kunstwerkcollage-transtopischer-teppich-10203686.

[3] Christian Guerematchi, ‘NAM – Non Aligned Movement teaser’, digital video. ICK Dans Amsterdam et al., 2021. YouTube, 1:00. https://youtu.be/5dh991XPHFs.

[4] Robert Robertson, ‘Glokalisierung — Homogenität und Heterogenität in Raum und Zeit’, in Perspektiven der Weltgesellschaft, ed. Ullrich Beck (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1998).

bibliography

Guerematchi, Christian. ‘NAM – Non Aligned Movement teaser’. digital video. ICK Dans Amsterdam, Amsterdams Fonds voor de Kunst, music/sound: Shishani, text/dramaturgy: Gita Hacham, costumes/design: Jonathan Ho and creative direction: PINKB!NK, 2021, YouTube, 1:00. https://youtu.be/5dh991XPHFs.

Önder, Tunay. Transtropischer Teppich. 2016. Carpet, paper, plastic, metal, digital material, 250 x 350 x 10 cm. Münchner Stadtmuseum, Sammlung Stadtkultur. https://sammlungonline.muenchner-stadtmuseum.de/objekt/kunstwerkcollage-transtopischer-teppich-10203686.

Robertson, Robert. ‘Glokalisierung — Homogenität und Heterogenität in Raum und Zeit’. In Perspektiven der Weltgesellschaft, edited by Ullrich Beck, Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1998.

Seeland, Peter. ‘Looking back on global dis:connect’s first annual conference: dis:connectivity in processes of globalisation: theories, methodologies, explorations’. static: thoughts and research from global dis:connect 2, no. 1 (2023): 77-81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5282/static/41.