In

Blog 2023

katharina wilkens

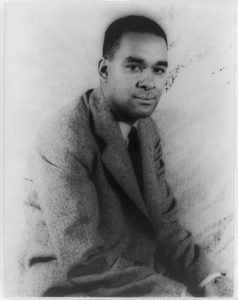

Richard Wright, the African American journalist, former communist, strict secularist and pan-African observer of the independence movements in late-colonial Africa, travelled to the Bandung Conference in Indonesia in 1955. His report from one the founding meetings of the Non-Aligned Movement, which was attended by many leaders from Asia and Africa, intertwines the themes of racism, colonialism, imperialism and communism in the Cold War era. The title

The Color Curtain borrows its imagery from the so-called ‘Iron Curtain’, dividing the Western from the Eastern bloc.

The USSR and People’s Republic of China were vying for hegemony in the communist world. A question raised, but also skilfully skirted at the conference, was how many of the newly emerging nations would be interested in allying with China or the USSR rather than the USA.

‘But is there not something missing here?’ asks Wright. ‘Weren’t all these men deeply religious? Christians? Moslems? Buddhists? Hindus? They were. Would they accept working with Red China? Yes, they would. Why? Were they dupes? No, they were desperate. They felt that they were acting in common defense of themselves. Then, is Christianity, as it was introduced into Asia and Africa, no deterrent to Communism?’ He answers his own question quite succinctly: ‘Obviously, religion, and particularly the Christian religion, was no bulwark against Communism’.[1]

Among the delegates in Bandung was Kwame Nkrumah, then prime minister of the Gold Coast which was still under British control. Richard Wright had visited him a few years earlier during his first journey through a continental African country, when Wright began to weave his own personal pan-African consciousness spanning both sides of the Atlantic. Nkrumah, together with Sékou Touré from Guinea, Léopold Sédar Senghor from Senegal, Julius Kambarage Nyerere from Tanganyika, Modibo Keïta from Mali and others, was a founding figure of African socialism.

[2] All of these leaders, however, insisted on the religious nature of their version of socialism. And they were not afraid to defend their religiosity against Chinese and especially Soviet accusations that they were violating the ‘true teachings’ of Marx and Lenin.

[3]

How to grasp the role of religion in African socialism

Wright’s confusion is understandable. Karl Marx famously criticised religion, particularly the Christian church(es), as part of the superstructure of capitalism. Both Lenin and Mao implemented atheist regimes and vigorously popularised atheist attitudes. Many African labourers and students in France and Great Britain in the 1920s and 1930s founded organisations combining pan-African and communist ideas.

[4] This earlier generation of freedom fighters often followed atheist ideals unlike the later, more pragmatic leaders of the African independence movements.

Nyerere and Senghor were both practicing Catholics, Touré and Keïta Muslims, Nkrumah and others were Protestants. None were shy about it. Indeed, they argued that their anti-atheist position was a distinction between African

socialism from Soviet-style

communism.

[5] Nkrumah writes: ‘Insistence on the secular nature of the state is not to be interpreted as a political declaration of war on religion, for religion is also a social fact and must be understood before it can be tackled’.

[6] For all leaders, Christianity and Islam were essential moral underpinnings of African socialism while also vital aspects of modernisation, progress and development. In the words of Senghor, ‘it is false to claim with the Marxists that Christianity and Islam scorned, or even neglected, the sciences’.

[7] While Wright might have balked at a sentence like this, the socio-political place of religion in the colonies differed from that in the metropoles.

Fig. 02: President Leopold Senghor Viewing African Art at the Musée Dynamique, During the Festival mondial des arts nègres (FESMAN), Dakar, 1966, African Art After Independence, 1957-1977, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, University of Michigan, https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/maa/research/art-of-a-continent/senghor-dakar-1966/.

Dis:connecting religion and civilisation

Studying the global spread of the concept of ‘religion’ (as opposed to church institutions), scholars of religion have noted its immense impact on the discursive construction of ‘civilisation’ and thence on the colonising strategies of European empires. Only ‘civilised humans’ have religions, so the Spanish argued, conversely implying that non-Christian ‘barbarians’ in South America in the early 1500s, for example, could be exploited.

[8] A couple of centuries later, Hegel dismissed Africans as ‘immoral barbarians’ without law, as ‘cannibals’ and as ‘fetishists’ without proper religion or even self-awareness. He argued that they ‘were not part of history’ because they were not ‘capable of development’.

[9] His arguments were often repeated in political and missionary discourse of colonial imperialism and occasionally resonate even today.

[10]

But even when academics, policy makers and colonial officials grudgingly began to accord African religion a place in history, the prevailing evolutionary theory placed ‘fetishism’, ‘animism’ and ‘ancestor worship’ on the lowest rung of religious development, thus denying Africans any indigenous civilisation. In their minds, civilisation could only be established alongside Western (and mostly Protestant) Christianity – David Livingstone’s three C’s of the colonial and missionary enterprise: Christianity, Civilisation and Commerce – held well into the first half of the 20th century.

In the 1930s, Western anthropologists were bent on salvaging indigenous cultures in books and museums because they thought them doomed under imperialism and secular modernity. Edward E. Evans-Pritchard, government anthropologist in southern Sudan and leading scholar of indigenous African religions among the Azande and Nuer. In the 1940s, South African anthropologist Meyer Fortes, himself a son of Russian Jewish refugees, was among the first to discuss the impact of colonialism on the religio-political-juridical system of ancestor veneration among the Talensi in northern Ghana.

Reconnecting with the African past

The counter movement followed from the early 1950s, when Christian theologians, both Western and African, began writing about indigenous religions in a new style. African religions were cast as ‘natural religions’ (rather than ‘heathendom’).

[11] In this argumentation, the god of Christian salvation worked through the gods and priests of African cosmology prior to Christianisation, allowing pious Africans into salvation history. Under the rise of nationalist ideology, religion as a marker of civilisation was thus restored to indigenous peoples. The image of ‘African Traditional Religion’ (ATR) created by these scholars was free of cannibalism and violence, instead emphasising community, beauty, natural philosophy, spirituality and unity across seemingly heterogenous traditions. Prominent writers in this vein from the 1940s to 1970s include Ghanaian politician and theologian Joseph Boakye Danquah, Ugandan theologian John Mbiti and Nigerian theologian Bolaji Idowu. However, despite their celebration of traditional religion, they agreed that it was passé. With the coming of Christ (through the colonial missionaries), Christianity was the way forward, albeit in thoroughly Africanised garb.

[12]

The leaders of African socialism were aware of these discursive positions in the disciplines of anthropology, history and theology, in which many held PhDs. In their publications, they consistently maintained that Africans had been ‘civilised’ people prior to the advent of the European colonisers; that their culture was morally advanced; and that their ancestral religions had the same worth as mission Christianity.

In 1943, Eduardo Mondlane, leader of the Mozambiquan liberation movement with a doctorate in anthropology, wrote in a letter to former Swiss missionary teacher and close friend André-Daniel Clerc:

I think that the beliefs placed in my heart by my grandmother about our ancestors had something to do with my spiritual progress. I believed that there was another life after death because my grandparents live in spirit (even though they are bodily dead). And from this when I heard the story of Christ and God I immediately accepted.[13]

Mondlane later added a further thought to his reflection on religion: ‘Our indigenous religion could have remained and continued to thrive if there had not been another which offered better answers to the questions of the future’.

[14] In emphasising the ancestral lineage of faith in God, Mondlane sets the indigenous way of life on par with Christianity-as-civilisation. Simultaneously, he concurs that the universal church (or rather, Africanised church and neither a specific national nor denominational church) was best suited to modernisation and national independence. While ancestral religion was seen positively there, it belonged to the past.

African scholars and independence-era writers tried hard to counter the Hegelian trope of African a-historicity. Notably, Cheikh Anta Diop, a Senegalese Egyptologist argued in his 1954 thesis

Nations Nègres et Cultures that ancient Egyptian civilisation was derived from the same black civilisation as that of West Africa. His contemporary Léopold Senghor pits the concept of Négritude against the French anthropologist Lucien Lévy-Bruhl’s theory of ‘pre-logical mentality’ and similar theories.

[15] He also emphasised that African religion was based on both reason and idealist ontology; it touched on life and meaning beyond the everyday, perceiving beauty and searching for the divine in nature.

[16] However, he opposed ‘magic’ to ‘animism’ (the Francophone alternative to ‘African Traditional Religion’, not the primitive religion of evolutionary theory). He considered ‘magic’ and particularly the so-called secret societies, or mask societies, who ostensibly practiced it, to be ‘a superstitious deformation, too human’.

[17]

In the discursive framework of Africanist history, anthropology and theology, ‘religion’ was a pre-condition of ‘civilisation’, which in turn was a pre-condition for independent rule, free of colonial paternalism. Though I am oversimplifying the complex economic and political negotiations of the independence movements, of course, the strategic role of the discursive figure of religion as the basis of civilisation – and thus modernity – must not be underestimated.

[18]

Disconnecting religion and culture

In Europe, however, public interest in religious and church matters declined steeply in the 1950s and 1960s, while theories of secularisation-as-modernisation abounded. Christianity and Islam had lost their discursive weight as harbingers of modernity while outright atheism, general agnosticism and New Age spirituality gained ground. Instead, culture and art (rather than Christianity) became arenas of communication about contemporary values, morality and visions for the future. In socialist states cultural propaganda became a preferred method of education and indoctrination.

In the nascent African nations, religion was not controversial. In contrast to Europe, however, Islam and Christianity (not indigenous religions) were seen positively because they offered global networks of moral support, education and development aid. Conversion accelerated in these decades, especially in urban areas. Political leaders, however, preferred the discursive formation of ‘culture’ when talking about the necessity of Africanisation as part of de-colonialisation and independence. Across the continent, presidents and ministers celebrated African culture, created ministries of national culture, instituted festivals and held dance, art and music competitions.

[19] Soviet-style realism in art, however, never outshone the policy of Africanisation, which favoured more abstract and expressionist styles.

[20]

In true socialist fashion, Nyerere, Touré, Senghor and other leaders combatted ‘backwardness’, ‘traditionalism’, ‘superstition’ and ‘witchcraft’. While Marx saw these forces reflected in Christianity and feudalism, the African leaders associated them with indigenous religion only. Ancestors were thus separated from their rituals. Mondlane, Senghor, Nkrumah and many others praised the tradition of African ancestor veneration as symbols of proto-socialist communalism, but never addressed them as spirits afflicting people through sickness and demanding bloody sacrifices as a remedy. The latter was ‘magic’.

Fig. 04: Leaders of the non-aligned movement, 1960 in New York (Jawaharlal Nehru, Kwame Nkrumah, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Sukarno, Yosip Tito), Intellivoire – Portal ouverte sur l’Afrique, Sommet Asie Afrique 60 ans après la conférence de Bandung, avril 20, 2015, https://intellivoire.net/sommet-asie-afrique-60-ans-apres-la-conference-de-bandung/.

In Guinea, Sékou Touré went furthest of all presidents in fighting so-called superstition, which he found in indigenous religions in mystical Sufi brotherhoods alike. Soviet Africanist I. Bochkarev supported this approach: ‘The Democratic Party [of Guinea] is aware of the need to dispel the religious myths with which the minds of the people are befuddled, and is taking steps in this direction’.

[21] In an effort to break the power of the local chiefs and sheikhs and to subsume them under party politics and national integration, Touré initiated a cultural revolution (modelled on China) and a programme of ‘demystification’. Ancestral mask dances were summarily forbidden in order to de-legitimise the chiefs’ power.

[22] This violent incursion into rural social structures (heavily aided by party secret service agencies) diverged from the celebration of annual pan-African festivals of art and culture that attracted performers from the Americas and throughout Africa.

The dis:connected legacy of African socialism

Today, after the Cold War and in an era characterised by religious resurgence, indigenous religious leaders are rallying and claiming their own public space while Pentecostal Christians and Salafists compete for political attention. What then is the legacy of African socialism, an ideology classified by Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni among the pre-eminent epistemologies of the Global South?

[23] The nationalist nostalgia for a unified ‘African culture’ was heavily critiqued by later generations. Nonetheless, ideas of ancestral communalism live on in Ubuntu, African Renaissance, Afrotopia and other post-colonial visions of Africa’s future.

By focussing on secularity and the negation of atheism in African socialism, the complexity of scholarly, political and activist networks with their attendant ideological dis:connections emerges. Mobile and well-educated pan-African activists managed the independence movements across three continents. They had to argue against Western orientalist and colonial scholarship that insisted Africans were not civilised because they had ‘no religion’, while simultaneously shaping smart alliances according to Cold War logics. Marxism and socialism were not born out of class struggle in an age of industrialisation, as Soviet commentators often criticised. The pan-African fight against racism and imperialism, however, lent itself easily to Marxist rhetoric, but without needing to declare war on Africanised Christianity and Islam.

Beyond these global discourses, political leaders in the nascent nations of Africa had to contend with local politics, rival chieftains, party opponents and eminent religious leaders. What emerged was a pan-African ideal of African socialism refracted in local implementations that differed widely across nations and over time. Connections on one level of discourse coincided with disconnections on other levels, even if the results might surprise astute contemporary observers, such as Richard Wright.

[1] Richard Wright, ‘The Color Curtain’, in

Black Power. Three Books from Exile (New York: Harper Perennial, 2008), 429–630. For a historical and contextual re-evaluation of Wright, see Michael E. Nowlin,

Richard Wright in Context (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

[2] William H. Friedland and Carl Gustav Rosberg, eds.,

African Socialism (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1964). I focus here on the 1950s and 1960s, when African leaders developed pre-independence arguments for self-rule and formulated early rules for national integration. These discourses had two audiences: the colonial governments in Europe and the local people who lived in these artificially created territories but spoke dozens of different languages and had previously lived in completely different kingdoms and chieftaincies. Ghana (the former Gold Coast) gained independence from the UK in 1958. Guinea followed in 1958, when it refused to join a new French constitutional arrangement in the colonies. Most Francophone and Anglophone countries were granted independence in 1960, while the Lusophone countries were involved in years of separatist wars through the 1960s and 1970s. At the height of the Cold War, independence required the African leaders to identify with and implement either socialism or capitalism — a fierce binary that most leaders overcame through their personality cults and that gave rise to distinct political atmospheres. African socialism, as described in this article, dominated continental public discourse at the time.

[3] Julius Kambarage Nyerere, ‘The Varied Paths to Socialism’, in

Freedom and Socialism. A Selection from Writings and Speeches 1965-1967 (Dar es Salaam: Oxford University Press, 1969), 301–10.

[4] Hakim Adi,

Pan-Africanism and Communism: The Communist International, Africa and the Diaspora, 1919-1939 (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2013); Holger Weiss,

Framing a Radical African Atlantic: African American Agency, West African Intellectuals, and the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers (Leiden: Brill, 2014).

[5] Léopold Sédar Senghor, ‘The Theory and Practice of Senegalese Socialism’, in

On African Socialism, trans. Mercer Cook (London: Pall Mall, 1964), 105–65; Nyerere, ‘Varied Paths’.

[6] Kwame Nkrumah,

Consciencism: Philosophy and Ideology for De-Colonization (London: Heinemann, 1964), 13.

[7] Senghor, ‘Theory and Practice’, 164.

[8] Jonathan Z. Smith, ‘Religion, Religions, Religious’, in

Critical Terms for Religious Studies, ed. Mark Taylor (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1998), 269–84; for a discussion of humanness, religion and Oxford scholarship before and after the Zulu wars in South Africa during the 19th century, see also David Chidester,

Savage Religion: Colonialism and Comparative Religion in Southern Africa (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996).

[9] Georg Friedrich Wilhelm Hegel,

Lectures on the Philosophy of World History. Introduction: Reason in History, ed. Johannes Hoffmeister, trans. Hugh Barr Nisbet (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1975), 173-190.

[10] This enduring view of African religion, culture and civilisation was repeated by the French president Nicolas Sarkozy on a state visit to Senegal which in turn triggered student protests and a wave of post-colonial debate. To take just one example, see the reaction by Achille Mbembe, ‘L’Afrique de Nicolas Sarkozy’,

Mouvements 4, no. 52 (2007): 65–73; Holger Weiss,

Framing a Radical African Atlantic: African American Agency, West African Intellectuals, and the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers (Leiden: Brill, 2014).

[11] In the 18th century, Enlightenment philosophers and deists such as David Hume began critising the teleology of church history as the only salvation of mankind. They disrupted the binary of Christendom and heathendom by including a category of ‘natural religion’, in which morality, spirituality and the knowledge of God were just as manifest as in the gospels (Smith,

Religion, Religions, Religious).

[12] Katharina Wilkens and Mariam Goshadze, ‘Indigenous Religions in West Africa’, in

Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023),

https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.1133.

[13] This and the following letter are cited in: Robert N. Faris,

Liberating Mission in Mozambique: Faith and Revolution in the Life of Eduardo Mondlane (Cambridge: Lutterworth Press, 2015): Robert N. Faris,

Liberating Mission in Mozambique: Faith and Revolution in the Life of Eduardo Mondlane (Cambridge: Lutterworth Press, 2023), 18.

[14] Faris,

Liberating Mission, 20.

[15] Léopold Sédar Senghor, ‘Vues sur L’Afrique noire ou: assimiler, non être assimilés’, in

Liberté I: Négritude et Humanisme, ed. Léopold Sédar Senghor (Paris: Éditions de Seuil, 1964), 36–69: 43. This essay was written in 1949.

[16] Léopold Sédar Senghor, ‘Éléments constructifs d’une civilisation d’inspiration négro-africaine’,

Présence Africaine 24/25, no. 1 (1959), 249–79.

[17] Léopold Sédar Senghor, ‘Ce que L’homme noir apport’, in

Liberté I: Négritude et Humanisme, ed. Léopold Sédar Senghor (Paris: Éditions de Seuil, 1964), 22–38: 36.

[18] There are many other reasons why Christianity and Islam continued to play important roles in African socialism. For religious biographies of the leaders, missionary education in general and the problem of the economic monopoly of Sufi brotherhoods in various trades and plantations, see Katharina Wilkens, ‘African Socialism: A Blueprint for Secular State Formation at the Time of Independence’, in

Working Paper Series of the CASHSS: Multiple Secularities – Beyond the West, Beyond Modernities (. University of Leipzig, open access (forthcoming), n.d.).

[19] Julius Kambarage Nyerere, ‘President’s Inaugural Address’, in

Freedom and Unity: A Selection from Writings and Speeches 1952-1965 (London: Oxford University Press, 1967), 186–87.; Léopold Sédar Senghor, ‘Fonction et Signification de Premier Festival Mondial Des Arts Nègres’, in

Liberté III: Négritude et Civilisation de L’Universel (Paris: Éditions de Seuil, 1977); Sékou Touré, ‘A Dialectical Approach to Culture’,

The Black Scholar 1, no. 1 (1969); for an overview of pan-African festivals, see Yair Hashachar, ‘Guinea Unbound: Performing Pan-African Cultural Citizenship Between Algiers 1969 and the Guinean National Festivals’,

Interventions 20, no. 7 (2018),

https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2018.1508932.

[20] Léopold Sédar Senghor, ‘L’ésthetique négro-africaine’, in

Liberté I: Négritude et Humanisme (Paris: Éditions de Seuil, 1964).

[21] I. Bochkarev, ‘The Guinean Experiment’,

New Times, no. 29 (1960): 28, quoted in Arthur Jay Klinghoffer,

Soviet Perspectives on African Socialism (Rutherford: Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 1969): 107.

[22] Ramon Sarró,

The Politics of Religious Change on the Upper Guinea Coast: Iconoclasm Done and Undone (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press for the International African Institute London, 2009).

[23] Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni,

Epistemic Freedom in Africa. Deprovincialization and Decolonization, Rethinking Development (London/New York: Routledge, 2018): 19-52 and Chapter 4, in which African Socialism is discussed under the broader term of African nationalist humanism.

Bibliography

Adi, Hakim.

Pan-Africanism and Communism: The Communist International, Africa and the Diaspora, 1919-1939. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2013.

Bochkarev, I. ‘The Guinean Experiment’.

New Times, no. 29 (1960).

Chidester, David.

Savage Religion: Colonialism and Comparative Religion in Southern Africa. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996.

Faris, Robert N.

Liberating Mission in Mozambique: Faith and Revolution in the Life of Eduardo Mondlane. Cambridge: Lutterworth Press, 2023.

Friedland, William H., and Carl Gustav Rosberg, eds.

African Socialism. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1964.

Hashachar, Yair. ‘Guinea Unbound: Performing Pan-African Cultural Citizenship Between Algiers 1969 and the Guinean National Festivals’.

Interventions 20, no. 7 (2018).

https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2018.1508932.

Hegel, Georg Friedrich Wilhelm.

Lectures on the Philosophy of World History. Introduction: Reason in History. Edited by Johannes Hoffmeister. Translated by Hugh Barr Nisbet. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1975.

Klinghoffer, Arthur Jay.

Soviet Perspectives on African Socialism. Rutherford: Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 1969.

Mbembe, Achille. ‘L’Afrique de Nicolas Sarkozy’.

Mouvements 4, no. 52 (2007): 65–73.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo J.

Epistemic Freedom in Africa. Deprovincialization and Decolonization. Rethinking Development. London/New York: Routledge, 2018.

Nkrumah, Kwame.

Consciencism: Philosophy and Ideology for De-Colonization. London: Heinemann, 1964.

Nowlin, Michael E.

Richard Wright in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Nyerere, Julius Kambarage. ‘President’s Inaugural Address’. In

Freedom and Unity: A Selection from Writings and Speeches 1952-1965, 186–87. London: Oxford University Press, 1967.

———. ‘The Varied Paths to Socialism’. In

Freedom and Socialism. A Selection from Writings and Speeches 1965-1967, 301–10. Dar es Salaam: Oxford University Press, 1969.

Sarró, Ramon.

The Politics of Religious Change on the Upper Guinea Coast: Iconoclasm Done and Undone. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press for the International African Institute London, 2009.

Senghor, Léopold Sédar. ‘Ce que L’homme noir apport’. In

Liberté I: Négritude et Humanisme, edited by Léopold Sédar Senghor, 22–38. Paris: Éditions de Seuil, 1964.

———. ‘Éléments constructifs d’une civilisation d’inspiration négro-africaine’.

Présence Africaine 24/25, no. 1 (1959): 249–79.

———. ‘Fonction et Signification de Premier Festival Mondial Des Arts Nègres’. In

Liberté III: Négritude et Civilisation de L’Universel. Paris: Éditions de Seuil, 1977.

———. ‘L’ésthetique négro-africaine’. In

Liberté I: Négritude et Humanisme, 202–2017. Paris: Éditions de Seuil, 1964.

———. ‘The Theory and Practice of Senegalese Socialism’. In

On African Socialism, translated by Mercer Cook, 105–65. London: Pall Mall, 1964.

———. ‘Vues sur L’Afrique noire ou: assimiler, non être assimilés’. In

Liberté I: Négritude et Humanisme, edited by Léopold Sédar Senghor, 36–69. Paris: Éditions de Seuil, 1964.

Smith, Jonathan Z. ‘Religion, Religions, Religious’. In

Critical Terms for Religious Studies, edited by Mark Taylor, 269–84. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1998.

Touré, Sékou. ‘A Dialectical Approach to Culture’.

The Black Scholar 1, no. 1 (1969).

Weiss, Holger.

Framing a Radical African Atlantic: African American Agency, West African Intellectuals, and the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers. Leiden: Brill, 2014.

Wilkens, Katharina. ‘African Socialism: A Blueprint for Secular State Formation at the Time of Independence’. In

Working Paper Series of the CASHSS: Multiple Secularities – Beyond the West, Beyond Modernities. University of Leipzig, open access (forthcoming), n.d.

Wilkens, Katharina, and Mariam Goshadze. ‘Indigenous Religions in West Africa’. In

Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.1133.

Wright, Richard. ‘The Color Curtain’. In

Black Power. Three Books from Exile, 429–630. New York: Harper Perennial, 2008.

citation information:

Continue Reading