In

Blog, Blog 2024

matthias leanza

How do empires end? What influence do the ties and divides that shape imperial formations have after their downfall? And in what sense is the nation-state a legacy of empire rather than its negation? My essay ponders these questions using the example of German colonialism. It looks at the evolution of the German colonial empire from the 1880s in light of its sudden demise following World War I, arguing that the nation-state — in Germany and overseas — was among its most important legacies. However, the nation-state could only become a legacy of German colonialism because anticolonial activists failed to convert the overseas empire into a federated entity. The attempt at federal reform may have been futile, but it would have significantly altered the historical trajectories of all countries involved. Therefore, despite being an unlikely outcome, this counterfactual provides a contrast to assess what nation-states ultimately are — a product of decaying empires.

Anticolonial federalism

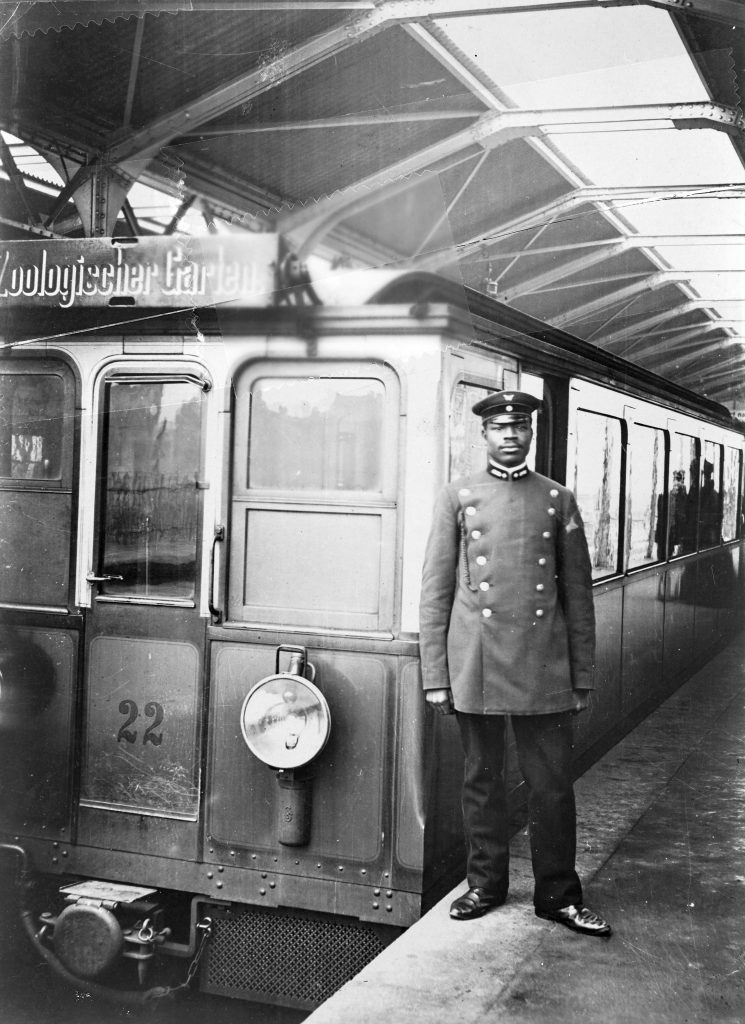

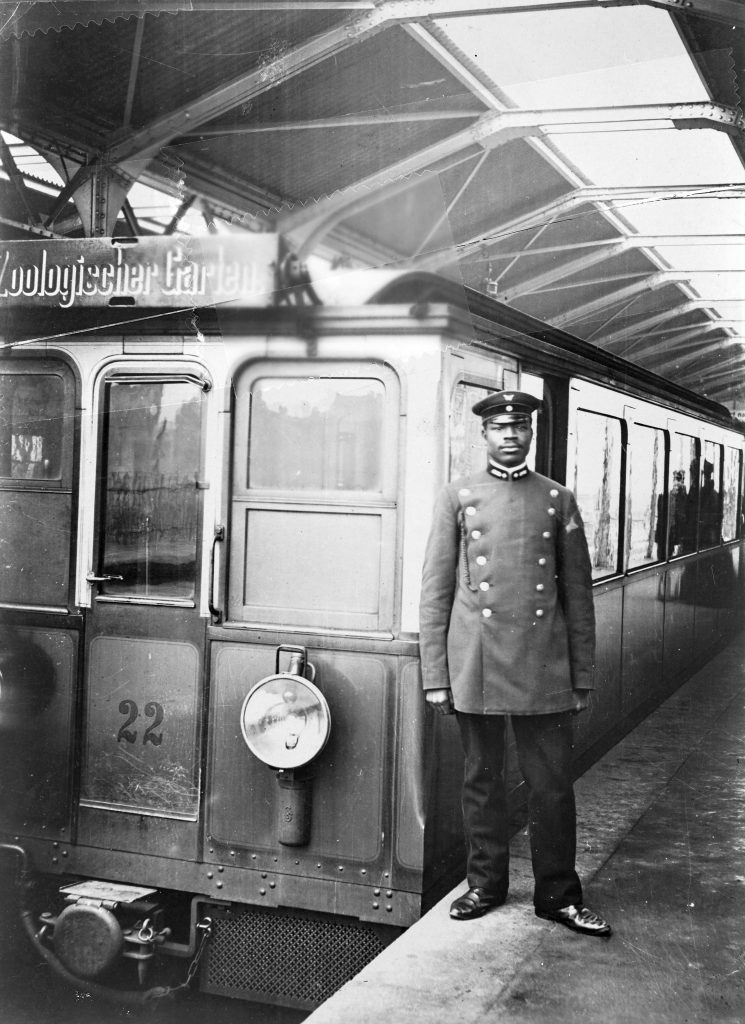

Fig. 1: Martin Dibobe as train driver in Berlin. (Image: Historisches Archiv der BVG)

On 27 June 1919, the day before Germany signed the Treaty of Versailles, Martin Dibobe (born Quane a Dibobe) submitted a petition to the German Colonial Office on behalf of the Duala people in Cameroon.

[1] This was not Dibobe’s first interaction with the Berlin authorities. Born to a Duala chief in 1876, Dibobe had been in Germany for over two decades by that point.

[2] He had come in 1896 to participate in a state-organised colonial exhibit at the Berlin Trade Fair, where 103 individuals from various German colonies were to present their ways of life to the public.

[3] After the fair, some decided to stay and settle in Germany, including Dibobe. He completed vocational training and subsequently worked as a train driver for Berlin’s urban rail and subway company. A fierce supporter of the November Revolution, Dibobe hoped to negotiate better terms for his people and extend the emergent republican order to the German colonies, all of which had been seized by the Entente Powers during the war. In June 1919, he organised a petition to the Weimar National Assembly with the support of 17 other members of the Duala community in Germany before turning to the Colonial Office again, as he had done on previous occasions.

[4]

The list of demands was extensive, but they all revolved around one core issue: Cameroon and the other German colonies in Africa were to remain with Germany. The residents of those territories were to be treated as Germans with equal rights and duties, regardless of their race or ethnicity.

[5] The petition proposed introducing the German civil code and judicial system, including the abolition of corporal punishment, indentured labour and all colonial laws enshrining racial segregation.

[6] At the same time, Cameroon was to maintain some degree of autonomy from Germany’s federal government — for example, by having three presidents of its own, each representing a different population group, and a separate tax fund — while obtaining permanent representation in the Reichstag.

[7] As the primary liaison between the Duala diaspora in Germany and Cameroon, Dibobe seemed to be the natural candidate for this office. The German government would retain the right to appoint Cameroon’s governor, who had to ensure law and order in the territory.

[8] However, the incumbent could be held accountable and even dismissed if the population expressed dissatisfaction with his performance. By contrast, all other public offices had to be occupied by people of African descent, thus establishing a permanent balance of power between the former metropole and the former colony. Although this proposal clearly distinguished between German citizens from Europe and German citizens from Africa, Dibobe left no doubt that the latter, too, were Germans in every sense of the word. ‘Since we are Germans’, he explained, ‘we demand equality, even if in public life we are always referred to as foreigners. This misapprehension must be eliminated by the present government through public announcements’.

[9]

These demands implied nothing less than the transformation of Germany’s colonial empire into a multiracial and transregional federation, where being German and being African were fully compatible. The proposal demonstrated that decolonisation did not necessarily mean secession, as it did in anticolonial nationalism.

[10] Instead, exit from empire could also involve attempts to reshape existing ties according to the principle of plurality. Dibobe represented a political stance best understood as anticolonial federalism, which combines elements of both connection and disconnection. Later generations of activists from various European colonies would adopt this stance independently of him, as it promised to reconcile equality with difference.

[11]

The Minister for the Colonies, Johannes Bell, one of the envoys who signed the peace treaty in Versailles, even briefly mentioned the Dualas’ petitions in the National Assembly.

[12] But in the end, Dibobe’s radical proposition for a postcolonial Africa, which was centred on federal integration rather than national independence, went unnoticed. In Bell’s account, the loyal people of Cameroon simply preferred to share their fate with Germany, preferring to perish together than become French spoils of war.

Double standards

Neither Dibobe’s plea for a federal reorganisation of the German colonial empire nor the widespread desire among the German population to retain their imperial status, as voiced by Bell and many other officials, had any chance of success. Dibobe lost his job and tried to return to Cameroon with his German wife and two of her children from a previous marriage in 1921, but they only managed to travel as far as Monrovia, where he had relatives.

[13] The pervasive rhetoric of national self-determination notwithstanding, the Entente Powers had no intention of abolishing colonial rule. Instead, self-determination became a justification for carving up the empires of the vanquished in Europe, while the overseas empires of the victors remained intact and even expanded through the mandate system.

[14] When discussing the terms of the peace deal, one deputy of the National Assembly, the high-profile conservative Arthur von Posadowsky-Wehner, expressed his discontent as follows: ‘There is so much talk among our enemies of the self-determination of peoples. Why doesn’t England introduce this right to self-determination in Ireland? Why doesn’t it introduce this principle in India? Well, one interprets things as one pleases’.

[15]

The recurrent theme of national self-determination had arisen in the National Assembly’s opening session in February 1919. Friedrich Ebert, the chairman of the Social Democratic Party, welcomed the elected deputies in his capacity as the head of the provisional government, particularly emphasising the female deputies present.

[16] Although women remained underrepresented — only 37 of the 423 deputies were women — they participated for the first time in the legislative process, evidencing that the November Revolution had infixed the principle of popular sovereignty. Invoking US President Wilson’s principles for the postwar order, Ebert maintained that the German people had earned favourable peace terms, including Germany’s reinstatement as a colonial power. They were just as much victims of Prussian militarism as the countries against which the German Reich had waged war: ‘The German people have fought for their right to self-determination at home; they cannot now cede it to the outside world’.

[17]

Certainly, the victors had a different idea for Germany’s future.

[18] As the peace treaty stipulated, the occupied German colonies were to be administered as League of Nations mandates based on a concept of imperial guardianship, while the country’s multiple border regions in Europe became part of neighbouring nation-states, some newly created.

[19] This uneven application of self-determination followed the colour line, deepening the North–South divide in the global political system.

For Germany, this regulation entailed a double loss of empire, both in Europe and overseas, which was met with a politics of resentment. During the war, when state borders were fluid, Germany’s imperial ambitions evolved into grandiose visions of hegemony over continental Europe and central Africa, but the war resulted in the opposite. Beyond being vanquished, the perceived relegation to an ‘ordinary’ nation-state without imperial peripheries prompted deep resentment.

[20] This sentiment is a desire for revenge despite, or because of, an inability to change the situation, giving birth to what Nietzsche called ‘indignant pessimists’.

[21] This affect is arguably what spurred the numerous protest rallies advocating for the return of the colonies in the run-up to the peace settlement, and it was clearly manifested in a revisionist discourse centred around the theme of the ‘lie of colonial guilt’.

[22] For the political campaigner Martin Hobohm, the loss of Germany’s colonial empire amounted to nothing less than the confinement of the German people in Europe, cutting the country off from its global lifelines.

[23]

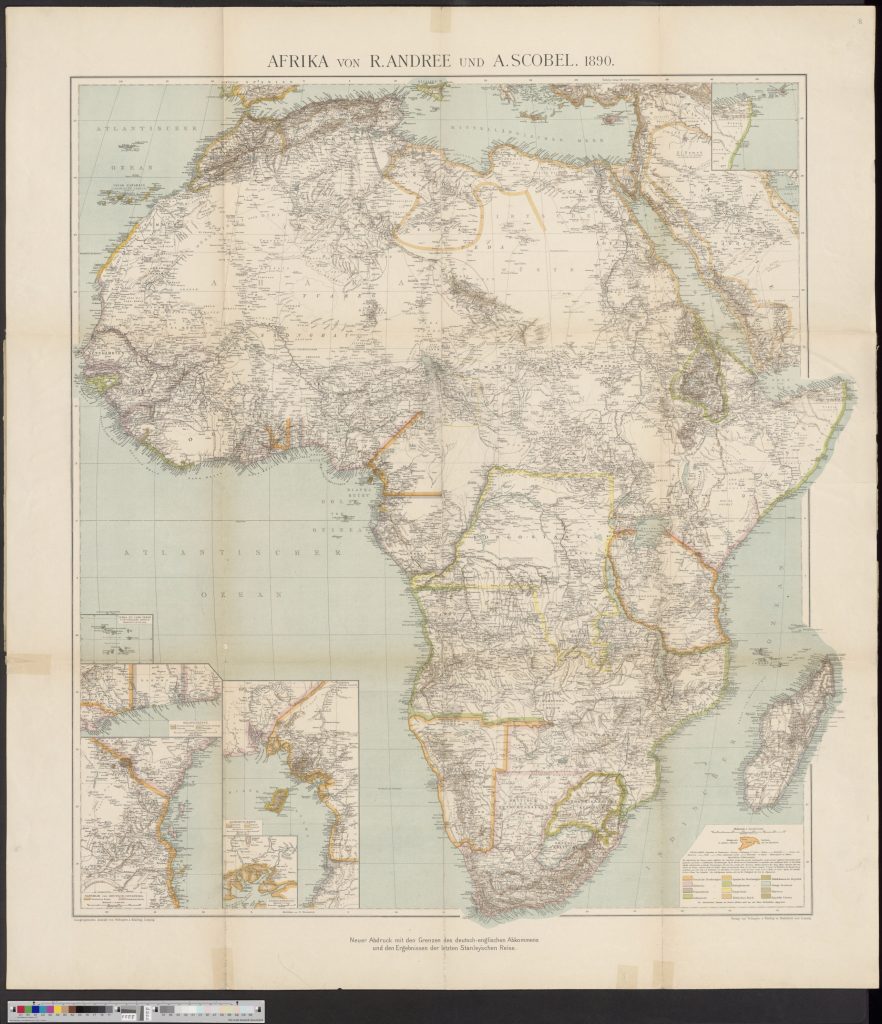

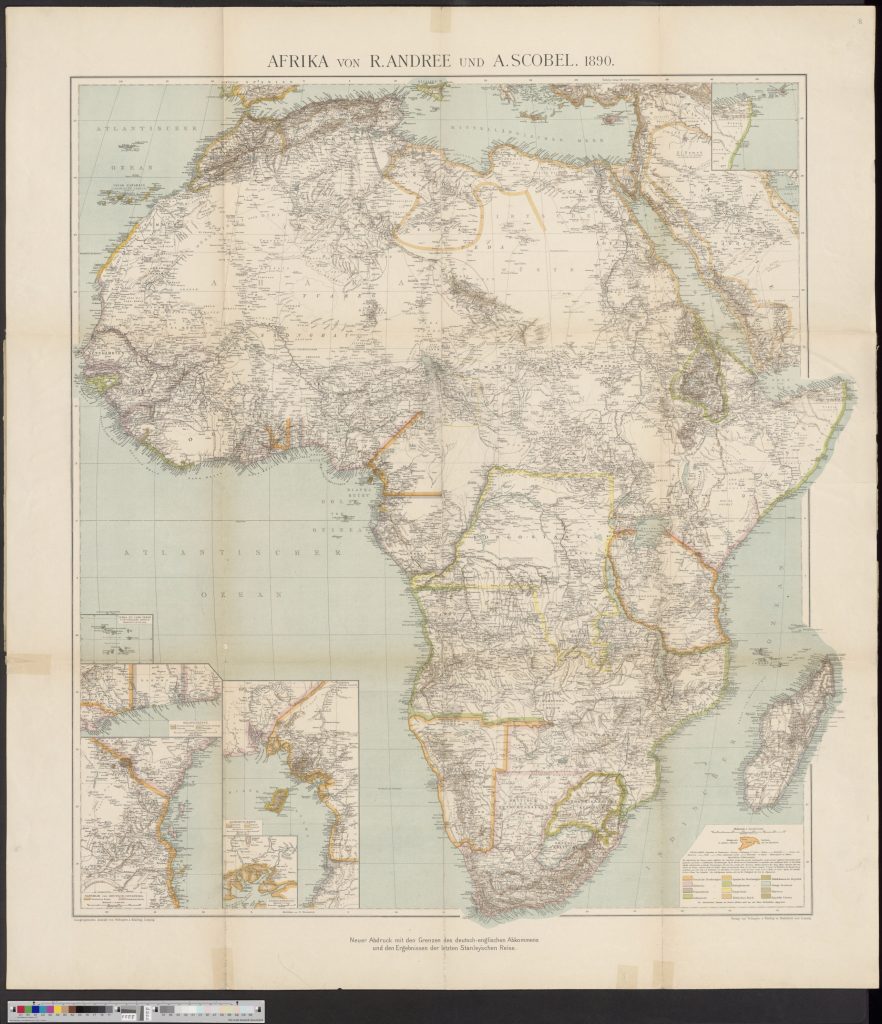

Fig. 2: Andree, R. and A. Scobel. 'Karte von Afrika'. Bielefeld: Velhagen & Klasing, 1890.

Spheres of influence

This view echoed a pervasive theme of colonialist discourse in Germany since the mid-19th century. Recalling Malthus, this discourse crystallised around the idea that colonial settlements represented a solution to overpopulation.

[24] Emigration could help curb unchecked population growth, but it created its own problems — most notably, the loss of able-bodied men and women to competing nations. Expanding on Adolf Zehlicke’s adaptation of Malthus to the German situation, Friedrich Fabri advocated in 1879 for the establishment of colonial settlements.

[25] To this end, a national emigration office was to be established and convert emigrants into settlers.

However, the first impulse toward realising this idea came from voluntary associations, not from the state. The German Colonial Association, founded in 1882, soon emerged as the key player. It was conceived as a national umbrella organisation to coordinate various local initiatives. At the inaugural meeting in Frankfurt, the explorer and founding member Hermann von Maltzan explained that the previous associations were too local to affect the national consciousness and politics. That is why it had become imperative to create a nationwide umbrella organisation.

[26] At the same time, Maltzan urged his fellow members to lower their expectations regarding the capabilities of such an entity. Establishing settler colonies was not yet viable. Fabri, who also attended the meeting, vehemently objected, arguing that only colonial settlements would forestall further population drain.

[27] The statutes that the assembly eventually adopted, however, were unequivocal: in keeping with the founding call, they rejected the maximalist program of settler colonies and constrained the organisation’s purpose to lobbying for trading colonies without participating in their establishment.

[28]

Germany thus had a national lobby organisation promoting colonial expansion, but it had no colonies — something that only began to change thanks to a disparate group of political entrepreneurs.

[29] In the early 1880s, various merchants and companies pushed for their ventures on the African coasts and in the Pacific to be protected by the German state. They hoped for a competitive advantage over other businesses, as foreign investors would either have to pay heavy tariffs or be excluded from the market. These scattered, largely uncoordinated initiatives took place in an international environment where competing powers jealously monitored each other’s expansion, which fuelled desires for territorial gains and fears of falling behind. The result was a self-reinforcing process of expansion that only halted when virtually all available territory had been claimed. The West Africa Conference of 1884–85 sought to regulate this process in its broad outlines, but expansion into the African interior and its piecemeal partition were organised in a decentralised manner through bilateral agreements.

[30] The expansion into the Pacific followed a similar pattern.

Thus, the European powers carved out their spheres of influence. Of course, this was not a new phenomenon, as a debate among legal scholars and political scientists around 1900 quickly established.

[31] The spheres, however, were comparatively small and gave rise to a patchwork of territorial claims. The imperial periphery could no longer be integrated into overarching hemispheres as in earlier times when far fewer powers were involved. Initially, these spheres were only defined near coastlines, while the hinterlands remained open as frontiers for potential expansion. Yet even after the borders had been settled, which in some cases took until the 1900s, these territories were far from evenly integrated. When the German Reich took them over from private companies and gradually established colonial states, they displayed a pronounced core–periphery structure.

[32] The reach of the colonial administration was limited to a core that faded into an active military frontier, pushing gradually into the hinterland. In virtually all colonies, some regions remained beyond colonial authorities’ control, often where local communities had already formed their own states. These regions represented an internal exterior, located within the sphere of influence but outside the colonial state.

This layered governance architecture informed how the victors of World War I redistributed the German colonies as mandated territories among themselves. For instance, the East African kingdoms of Burundi and Rwanda, administered by the Germans on the model of indirect rule, were transferred to Belgium, while Tanganyika fell under British control. It is nonetheless remarkable how enduring the borders of the originally established spheres of influence have proven. Even a century later, around three-quarters of the land borders established under German rule persist today.

[33] Together with the borders changed in the interwar period, they represent the fault lines along which the colonial empires disintegrated in the decolonisation that followed World War II, leaving territorial fragments behind that underlay postcolonial nation building.

[34]

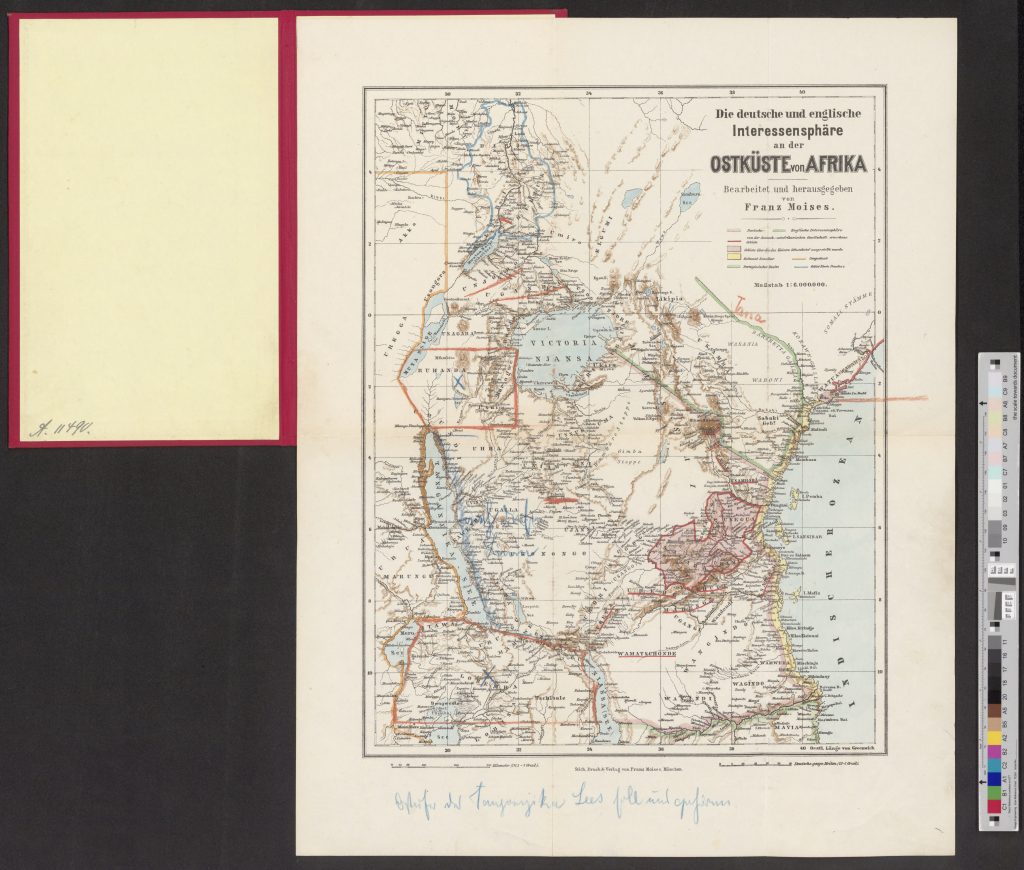

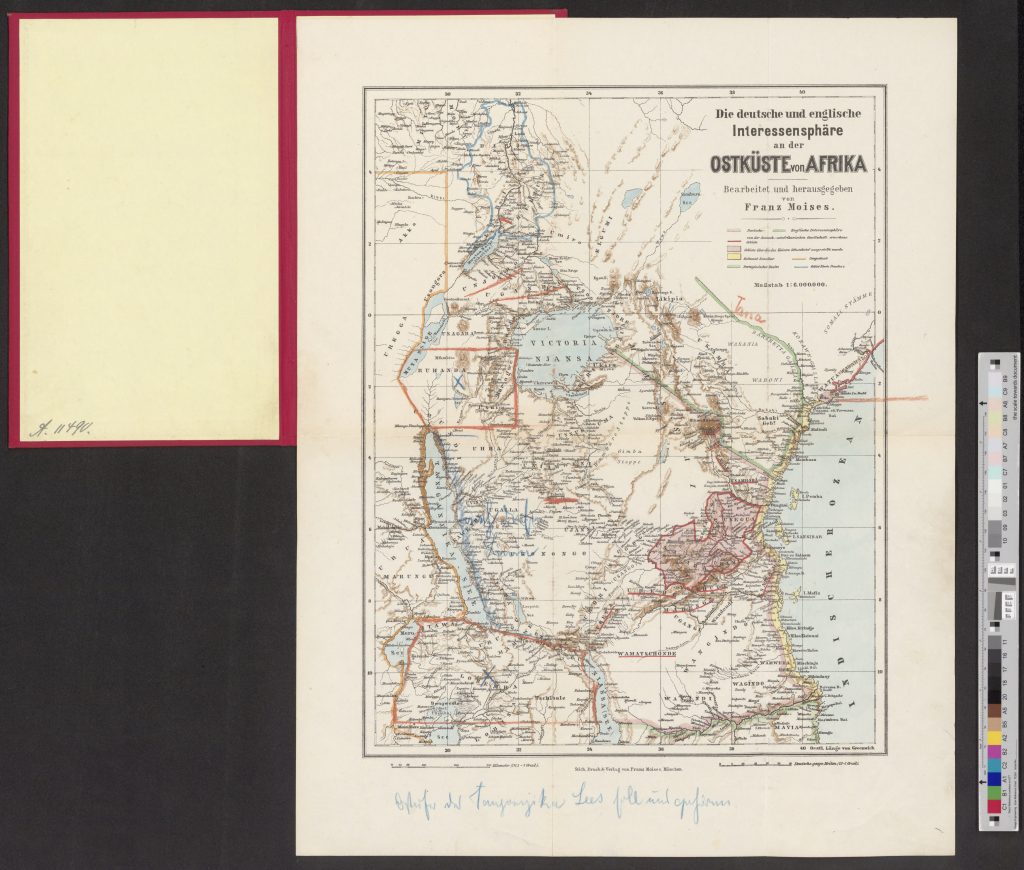

Fig. 3: 'Die deutsche und englische Interessensphäre an der Ostküste von Afrika'. Munich: Franz Moises, 1889.

In the public eye

The colonial empire also left a lasting imprint on the metropole and its political system. As already indicated, the loss of Germany’s status as a colonial power coincided with an internal reorganisation that transformed the country into a republic. Max Weber, who was directly involved in the preparation of the draft constitution by the Ministry of the Interior, suggested as early as December 1918 replacing the office of the Kaiser with a democratically elected president.

[35] As a political official, the president’s job was to counterbalance the bureaucracy with its rational, legal orientation and bring an element of charismatic leadership into the state machinery. If Weber had had his way, the new constitution would have omitted the federalist aspects of the German state altogether. But he was well aware that such a radical change had no chance for political reasons — the Entente Powers would never allow it.

[36]

Nevertheless, the constitution endowed the Reich president with far-reaching powers. These included the right to dissolve the Reichstag and the prerogative to appoint the government, which consisted of the chancellor and his ministers.

[37] However, as the central organ of the legislative branch, the Reichstag could hold the government accountable and even withdraw its confidence, while the Federal Council (

Reichsrat), the representation of the states on the national level, maintained a back seat in the political process.

[38]

This power-sharing arrangement was the result of developments that had been underway for several decades by that point, developments that had been fuelled by Germany’s overseas expansion. It is true that the German colonies were mainly governed by ordinances and decrees, rather than by proper law, which made it easy to circumvent parliament with its legislative powers.

[39] In addition, decisions regarding the overseas empire were at the discretion of the Kaiser, who, on behalf of the Reich, exercised sovereignty (

Schutzgewalt) over the colonies, officially referred to as protectorates (

Schutzgebiete).

[40] This meant the Kaiser alone could decide on spending the revenues generated by the colonies, but this was precisely the problem. The colonies’ inability to support themselves financially gave the Reichstag a powerful lever. Because this situation was not expected to change, the Reich leadership decided early on to show goodwill and involve the Reichstag in determining the overall colonial budget, not just the subsidies.

[41] Thus, the national parliament drew strength from the financial weakness of the overseas empire.

Each year, from January to March, parliament transformed into a public forum where representatives from various parties ruminated on Germany’s colonial affairs. The spokesperson of the Reichstag’s Budget Commission, Ludwig Bamberger, set the tone in 1891. As was to become customary in future budget debates, he briefly addressed some technical issues before moving on to an hour-long assessment of the colonial policy.

[42] The head of the Colonial Department in the Foreign Office, the legal expert Paul Kayser, responded right away, making some corrections and explaining his department’s policy.

[43]

Although the Reich leadership could usually secure majorities for its budget proposals, the Reichstag showered it with criticism during the legislative process. Each party used the colonial issue to raise its profile.

[44] Above all, however, they collectively created a counterpart — the government — whose members had to explain themselves to the public. A particularly strong catalyst for this development were the countless cases of violent misconduct by colonial officials that impelled the government to act.

[45] For example, Kayser maintained in 1893 that no abuse of office across the colonies had ever come to his attention.

[46] The Reichstag made sure that this would soon change. In early 1894, the Social Democrats placed some hippo whips and other instruments of torture on display in the Reichstag building, explaining that they had come directly from Cameroon.

[47] Just the day before, August Bebel had raised the brutal flogging of the wives of Dahomey soldiers ordered by Cameroon’s deputy governor, Heinrich Leist.

[48] Reich Chancellor Caprivi, who attended the session, felt compelled to react and rejected the allegations against Leist.

[49] However, his refusal to take responsibility elicited criticism, even from the conservative parties, recalibrating expectations regarding the accountability of senior government officials.

[50] Tensions peaked in 1906 when the Reichstag denied additional funds for the contentious war against Herero and Nama in South West Africa. In a bold move, the government dissolved parliament, asserting its constitutional dominance in this trial of strength.

[51] But this incident also revealed the undeniable influence the Reichstag had gained over national politics. The colonial empire made no small contribution to this structural transformation, which bolstered a core institution of the emergent German nation-state. Its effects would outlast the colonial era, forming part of its enduring legacy.

[1] 32-point petition to the Imperial Colonial Office in Berlin, personally submitted by Martin Dibobe together with Thomas Manga Akwa on June 27, 1899, BArch, R 1001/7220, 224–9. A reproduction can be found in Adolf Rüger, 'Imperialismus, Sozialformismus und antikoloniale demokratische Alternative: Zielvorstellungen von Afrikanern in Deutschland im Jahre 1919',

Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenchaft 23, no. 7 (1975).

[2] For a biographical sketch, see Eve Rosenhaft and Robbie Aitken, 'Martin Dibobe', in

Unbekannte Biographien: Afrikaner im deutschsprachigen Europa vom 18. Jahrhundert bis zum Ende des Zweiten Weltkrieges, ed. Ulrich van der Heyden (Berlin: Kai Homilius, 2008).

[3] Anne Dreesbach,

Gezähmte Wilde: Die Zurschaustellung "exotischer Menschen" in Deutschland 1870-1940 (Frankfurt: Campus, 2005); George Steinmetz, 'Empire in Three Keys: Forging the Imperial Imaginary at the 1896 Berlin Trade Exhibition',

Thesis Eleven 139, no. 1 (2017).

[4] Stefan Gerbing,

Afrodeutscher Aktivismus: Interventionen von Kolonisierten am Wendepunkt der Dokolonisierung Deutschlands 1919 (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2010), 57-60; Andreas Eckert,

Die Duala und die Kolonialmächte: Eine Untersuchung zu Widerstand, Protest und Protonationalismus in Kamerun vor dem Zweiten Weltkrieg (Münster: Lit, 1991), 216-25.

[5] Points 1 and 20.

[6] Points 2 t0 4.

[7] Points 26, 27 and 31.

[8] Points 5, 7 and 15.

[9] Point 20. Unless otherwise indicated, all translations are by the author.

[10] Erez Manela,

The Wilsonian Moment: Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007); Michael Goebel,

Anti-Imperial Metropolis: Interwar Paris and the Seeds of Third World Naitonalism (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

[11] Frederick Cooper,

Citizenship between Empire and Nation: Remaking France and French Africa, 1945-1960 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014); Adom Getachew,

Worldmaking after Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019); Frederick Cooper and Jane Burbank,

Post-Imperial Possibilities: Eurasia, Eurafrica, Afroasia (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2023).

[12] 'Proceedings of the German National Constituent Assembly, 96th Session', 330 (11 October 1919): 3023.

[13] Robbie Aitken and Eve Rosenhaft,

Black Germany: The Making and Unmaking of a Diaspora Community, 1884-1960 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 103, 07-08.

[14] Robert Gerwarth,

The Vanquished: Why the First World War Failed to End, 1917-1923 (London: Penguin, 2017); Mark Mazower,

Governing the World: The History of an Idea, 1815 to the Present (New York: Penguin, 2012), ch. 5-6.

[15] 'Proceedings of the German National Constituent Assembly, 40th Session', 327 (22 June 1919): 1122.

[16] 'Proceedings of the German National Constituent Assembly, 1st Session', 326 (6 February 1919): 1.

[17] 'Proceedings of the German National Constituent Assembly, 1st Session', 2.

[18] Margaret MacMillan,

Peacemakers: Six Months that Changed the World (London: John Murray, 2001), ch. 13-16.

[19] See also Susan Pedersen,

The Guardians: The League of Nations and the Crisis of Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015).

[20] Sean Andrew Wempe,

Revenants of the German Empire: Colonial Legacies, Imperialism, and the League of Nations (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

[21] Friedrich Nietzsche, 'Nachgelassene Fragmente: Anfang 1888 bis Anfang Januar 1889', in

Kritische Gesamtausgabe, ed. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, vol. 8.3, (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1972), 219.

[22] There were at least 84 such rallies between December 1918 and March 1919, as documented in BArch, R 1001/7220, 262–72. The term ‘lie of colonial guilt’ was popularised by Heinrich Schnee,

Die Koloniale Schuldlüge (Munich: Süddeutsche Monatshefte, 1924).

[23] Martin Hobohm,

Wir brauchen Kolonien (Berlin: Engelmann, 1918), 23..

[24] Klaus J. Bade,

Friedrich Fabri und der Imperialismus in der Bismarckzeit: Revolution - Depression - Expansion (Freiburg: Atlantis, 1975), 135-44. See also Sebastian Conrad,

Globalisation and the Nation in Imperial Germany, trans. Sorcha O´Hagan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

[25] Freidrich Fabri,

Bedarf Deutschland der Colonien (Gotha: Perthes, 1879), 86.

[26] Hermann von Maltzan,

Rede des Freiherrn Hermann von Maltzan auf der constituierenden Generalversammlung des Deutschen Kolonialvereins zu Frankfurt am Main am 6. Dezember 1882 (Berlin: Julius Sittenfeld, 1882).

[27] Report in

Frankfurter Journal und Frankfurter Presse on 6 December 1882, BArch, R 8023/253, 46.

[28] Statutes of the German Colonial Association in Frankfurt, BArch, R 8023/253, 68–9.

[29] For recent studies, see Kim Sebastian Todzi,

Unternehmen Weltaneignung: Der Woermann-Konzern und der deutsche Kolonialismus 1837-1916 (Göttingen: Wallstein, 2023); Dietman Pieper,

Zucker, Schnaps und Nilpferdpeitsche: Wie Hanseatische Kaufleute Deutschland zur Kolonialherrschaft trieben (Munich: Piper, 2023).

[30] Norbert Berthold Wagner,

Die deutschen Schutzgebiete: Erwerb, Organisation und Verlust aus juristischer Sicht (Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2002), 172-74.

[31] Martin Hasenjäger,

Der völkerrechtliche Begriff der "Interessensphäre" und des "Hinterlandes" im System der außereuropäischen Gebietserwerbungen (Greifswald: Kunike, 1907); Andreas Weissmüller,

"Die Interessensphären:" Eine kolonialrechtliche Studie mit besonderer Berücksichtigung von Deutschland (Würzburg: Boegler, 1908).

[32] For example, see Giorgio Miescher,

Namibia's Red Line: The History of a Veterinary and Settlement Border (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

[33] For more information, see

African Boundaries: A Legal and Diplomatic Encyclopaedia, ed. Ian Brownlie and Ian R. Burns (London: C. Hurst & Co, 1979).

[34] Jörg Fisch,

The Right of Self-Determination of Peoples: The Domestication of an Illusion, trans. Anita Mage (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 203-17.

[35] Max Weber, 'Aufzeichnung über die Verhandlungen im Reichsamt des Innern über die Grundzüge des der verfassungsgebenden deutschen Nationalversammlung vorzulegenden Verfassungsentwurfs vom 9. bix 12. Dezember 1918', in

Gesamtausgabe, ed. Wolfgang J. Mommsen and Wolfgang Schwentker, vol. 16: Zur Neuordnung Deutschlands, (Tübingen: Mohr, 1988), 56-90; Weber, 'Deutschlands künftige Staatsform', 98-146.

[36] Weber, 'Aufzeichnung über die Verhandlungen', 57.

[37] Ernst Rudolf Huber,

Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte seit 1789, vol. 6: Die Weimarer Reichsverfassung (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1981), 307-28.

[38] Huber,

Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte, 349-89.

[39] Harald Sippel, 'Recht und Gerichtsbarkeit', in

Die Deutschen und Ihre Kolonien: Ein Überblick, ed. Horst Gründer and Hermann Hiery (Berlin: be.bra, 2018), 201-21; Wagner,

Die deutschen Schutzgebiete, 304-06, 14-19. See also Marc Grohmann,

Exotische Verfassung: Die Kompetenzen des Reichstags für die deutschen Kolonien in Gesetzgebung und Staatsrechtswissenschaft des Kaiserreichs (1884-1914) (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2001).

[40] Wagner,

Die deutschen Schutzgebiete, 273-82.

[41] Grohmann,

Exotische Verfassung, 70-76.

[42] 'Proceedings of the Reichstag, 131st session', 118 (1 December 1891): 3172-78.

[43] 'Proceedings of the Reichstag, 131st session', 3178-79.

[44] Woodruff D. Smith,

The German Colonial Empire (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1978), 143-50.

[45] For a vivid case study, see Rebekka Habermas,

Skandal in Togo: Ein Kapitel deutscher Kolonialherrschaft (Frankfurt: Fischer, 2016).

[46] 'Proceedings of the Reichstag, 55th session', 128 (1 March 1893): 1346.

[47] 'Proceedings of the Reichstag, 53rd session', 134 (19 February 1894): 1340. However, the instruments of punishment were laid out the previous Saturday, 17 February.

[48] 'Proceedings of the Reichstag, 51st session', 134 (16 February 1894): 1294-95.

[49] 'Proceedings of the Reichstag, 51st session', 1295.

[50] 'Proceedings of the Reichstag, 51st session', 1296.

[51] Erik Grimmer-Solem,

Learning Empire: Globalization and the German Quest for World Status, 1875-1919 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 344-49.

bibliography

African Boundaries: A Legal and Diplomatic Encyclopaedia. Edited by Ian Brownlie and Ian R. Burns. London: C. Hurst & Co, 1979.

Aitken, Robbie and Eve Rosenhaft.

Black Germany: The Making and Unmaking of a Diaspora Community, 1884-1960. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Bade, Klaus J.

Friedrich Fabri und der Imperialismus in der Bismarckzeit: Revolution - Depression - Expansion. Freiburg: Atlantis, 1975.

Conrad, Sebastian.

Globalisation and the Nation in Imperial Germany. Translated by Sorcha O´Hagan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Cooper, Frederick.

Citizenship between Empire and Nation: Remaking France and French Africa, 1945-1960. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014.

Cooper, Frederick and Jane Burbank.

Post-Imperial Possibilities: Eurasia, Eurafrica, Afroasia. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2023.

Dreesbach, Anne.

Gezähmte Wilde: Die Zurschaustellung "exotischer Menschen" in Deutschland 1870-1940. Frankfurt: Campus, 2005.

Eckert, Andreas.

Die Duala und die Kolonialmächte: Eine Untersuchung zu Widerstand, Protest und Protonationalismus in Kamerun vor dem Zweiten Weltkrieg. Münster: Lit, 1991.

Fabri, Freidrich.

Bedarf Deutschland der Colonien. Gotha: Perthes, 1879.

Fisch, Jörg.

The Right of Self-Determination of Peoples: The Domestication of an Illusion. Translated by Anita Mage. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Gerbing, Stefan.

Afrodeutscher Aktivismus: Interventionen von Kolonisierten am Wendepunkt der Dokolonisierung Deutschlands 1919. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2010.

Gerwarth, Robert.

The Vanquished: Why the First World War Failed to End, 1917-1923. London: Penguin, 2017.

Getachew, Adom.

Worldmaking after Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019.

Goebel, Michael.

Anti-Imperial Metropolis: Interwar Paris and the Seeds of Third World Naitonalism. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Grimmer-Solem, Erik.

Learning Empire: Globalization and the German Quest for World Status, 1875-1919. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Grohmann, Marc.

Exotische Verfassung: Die Kompetenzen des Reichstags für die deutschen Kolonien in Gesetzgebung und Staatsrechtswissenschaft des Kaiserreichs (1884-1914). Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2001.

Habermas, Rebekka.

Skandal in Togo: Ein Kapitel deutscher Kolonialherrschaft. Frankfurt: Fischer, 2016.

Hasenjäger, Martin.

Der völkerrechtliche Begriff der "Interessensphäre" und des "Hinterlandes" im System der außereuropäischen Gebietserwerbungen. Greifswald: Kunike, 1907.

Hobohm, Martin.

Wir brauchen Kolonien. Berlin: Engelmann, 1918.

Huber, Ernst Rudolf.

Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte seit 1789, vol. 6: Die Weimarer Reichsverfassung. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1981.

MacMillan, Margaret.

Peacemakers: Six Months that Changed the World. London: John Murray, 2001.

Manela, Erez.

The Wilsonian Moment: Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Mazower, Mark.

Governing the World: The History of an Idea, 1815 to the Present. New York: Penguin, 2012.

Miescher, Giorgio.

Namibia's Red Line: The History of a Veterinary and Settlement Border. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. 'Nachgelassene Fragmente: Anfang 1888 bis Anfang Januar 1889'. In

Kritische Gesamtausgabe, edited by Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, Vol. 8.3. Berlin: De Gruyter, 1972.

Pedersen, Susan.

The Guardians: The League of Nations and the Crisis of Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Pieper, Dietman.

Zucker, Schnaps und Nilpferdpeitsche: Wie Hanseatische Kaufleute Deutschland zur Kolonialherrschaft trieben. Munich: Piper, 2023.

'Proceedings of the German National Constituent Assembly, 1st Session'. 326 (6 February 1919).

'Proceedings of the German National Constituent Assembly, 40th Session'. 327 (22 June 1919).

'Proceedings of the German National Constituent Assembly, 96th Session'. 330 (11 October 1919).

'Proceedings of the Reichstag, 51st session'. 134 (16 February 1894).

'Proceedings of the Reichstag, 53rd session'. 134 (19 February 1894).

'Proceedings of the Reichstag, 55th session'. 128 (1 March 1893).

'Proceedings of the Reichstag, 131st session'. 118 (1 December 1891).

Rosenhaft, Eve and Robbie Aitken. 'Martin Dibobe'. In

Unbekannte Biographien: Afrikaner im deutschsprachigen Europa vom 18. Jahrhundert bis zum Ende des Zweiten Weltkrieges, edited by Ulrich van der Heyden, Berlin: Kai Homilius, 2008.

Rüger, Adolf. 'Imperialismus, Sozialformismus und antikoloniale demokratische Alternative: Zielvorstellungen von Afrikanern in Deutschland im Jahre 1919'.

Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenchaft 23, no. 7 (1975): 1293-308.

Schnee, Heinrich.

Die Koloniale Schuldlüge. Munich: Süddeutsche Monatshefte, 1924.

Sippel, Harald. 'Recht und Gerichtsbarkeit'. In

Die Deutschen und Ihre Kolonien: Ein Überblick, edited by Horst Gründer and Hermann Hiery, Berlin: be.bra, 2018.

Smith, Woodruff D.

The German Colonial Empire. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1978.

Steinmetz, George. 'Empire in Three Keys: Forging the Imperial Imaginary at the 1896 Berlin Trade Exhibition'.

Thesis Eleven 139, no. 1 (2017): 46-68.

Todzi, Kim Sebastian.

Unternehmen Weltaneignung: Der Woermann-Konzern und der deutsche Kolonialismus 1837-1916. Göttingen: Wallstein, 2023.

von Maltzan, Hermann.

Rede des Freiherrn Hermann von Maltzan auf der constituierenden Generalversammlung des Deutschen Kolonialvereins zu Frankfurt am Main am 6. Dezember 1882. Berlin: Julius Sittenfeld, 1882.

Wagner, Norbert Berthold.

Die deutschen Schutzgebiete: Erwerb, Organisation und Verlust aus juristischer Sicht. Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2002.

Weber, Max. 'Aufzeichnung über die Verhandlungen im Reichsamt des Innern über die Grundzüge des der verfassungsgebenden deutschen Nationalversammlung vorzulegenden Verfassungsentwurfs vom 9. bix 12. Dezember 1918'. In

Gesamtausgabe, edited by Wolfgang J. Mommsen and Wolfgang Schwentker, Vol. 16: Zur Neuordnung Deutschlands. Tübingen: Mohr, 1988.

———. 'Deutschlands künftige Staatsform'. In

Gesamtausgabe, edited by Wolfgang J. Mommsen and Wolfgang Schwentker, Vol. 16: Zur Neuordnung Deutschlands. Tübingen: Mohr, 1988.

Weissmüller, Andreas.

"Die Interessensphären:" Eine kolonialrechtliche Studie mit besonderer Berücksichtigung von Deutschland. Würzburg: Boegler, 1908.

Wempe, Sean Andrew.

Revenants of the German Empire: Colonial Legacies, Imperialism, and the League of Nations. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

citation information

Leanza, Matthias, 'The German colonial empire, seen from its end', Ben Kamis ed. global dis:connect blog. Käte Hamburger Research Centre global dis:connect, 30 April 2024, https://www.globaldisconnect.org/04/30/the-german-colonial-empire-seen-from-its-end/.

Continue Reading

Fig. 2: Andree, R. and A. Scobel. 'Karte von Afrika'. Bielefeld: Velhagen & Klasing, 1890.

Fig. 2: Andree, R. and A. Scobel. 'Karte von Afrika'. Bielefeld: Velhagen & Klasing, 1890.

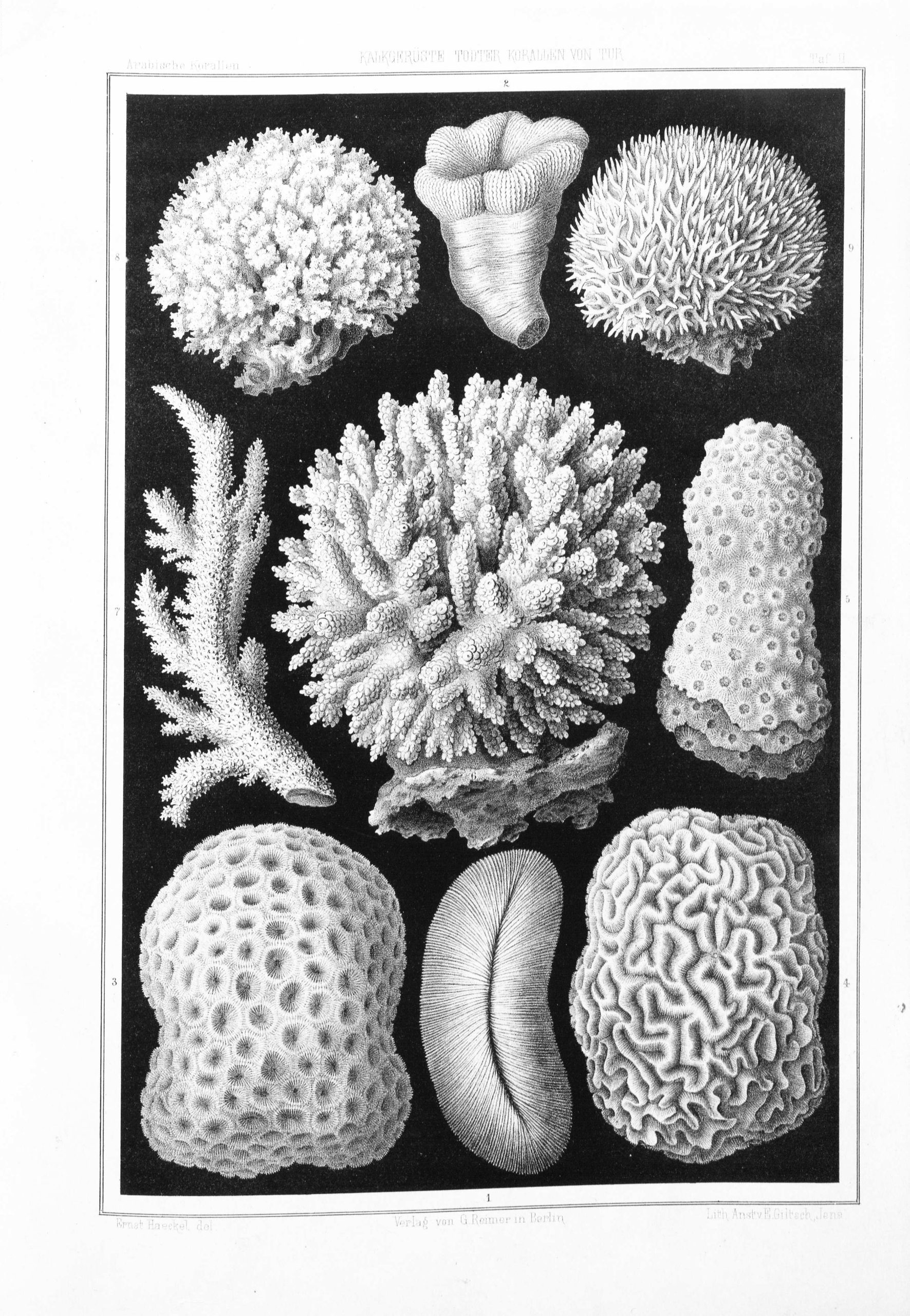

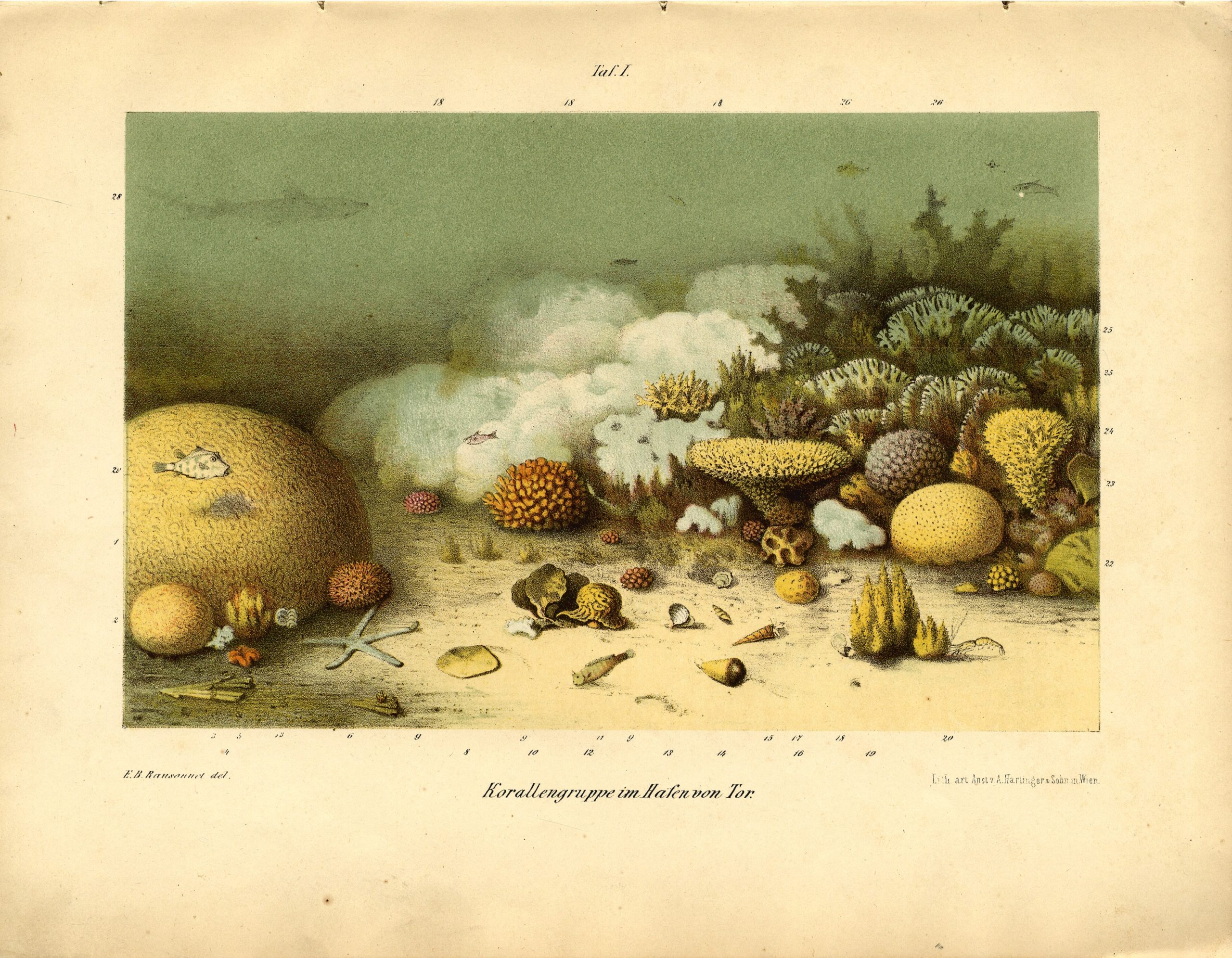

With his 1873 journey, Haeckel explicitly followed in the footsteps of the natural scientist Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg, who had already travelled to the Red Sea in 1832 and had taken up quarters in El Tor to study coral species in their natural habitat.

With his 1873 journey, Haeckel explicitly followed in the footsteps of the natural scientist Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg, who had already travelled to the Red Sea in 1832 and had taken up quarters in El Tor to study coral species in their natural habitat.

Image: Ben Kamis

Image: Ben Kamis The global dis:connect team.

The global dis:connect team. Seeking to learn from other empires: the German colonial officer Glauning translated into German this British manual for military expeditions in Africa.

Seeking to learn from other empires: the German colonial officer Glauning translated into German this British manual for military expeditions in Africa. Wissmann‘s famous colonial handbook, published 1895. Already on its first page, it recommended its readers to study the British colonial wars.

Wissmann‘s famous colonial handbook, published 1895. Already on its first page, it recommended its readers to study the British colonial wars.