In

Blog 2023

Looking back on global dis:connect’s first annual conference: Dis:connectivity in processes of globalisation: theories, methodologies, explorations

peter seeland

The global:disconnect annual conference took place from 20 to 21 October 2022, and it sought to clarify methodological and theoretical questions as well as to reflect on our research in general. By investigating global dis:connections, the Centre is inaugurating a new research programme. It emphasises the roles of delays and detours, of interruptions and resistances, of the active absence of connections in globalisation processes and investigates their social significance. One of the starting premises is that connectivity and disconnectivitity are not dichotomous; they are, rather, mutually constitutive in a relationship we call ‘dis:connectivity’. Fundamental methodological questions about how to research dis:connectivity remain to be answered. The central terms and how to apply them also demand attention. Multi-perspectival research on dis:connectivity fosters interdisciplinary dialogue on these questions. The conference also served as a space for just such a dialogue. Artists and scholars interacted, with each side gaining the benefit of exposure to the other. The conference comprised three thematic panels — absences, detours and interruptions —to structure and concretise the discourse.Richard M. Kabiito opened the event with the panel on absences. With a paper on Globalising Ugandan art: remixing the contest between tradition and modernity, Kabiito posed the question of absence and dis:connectivity in postcolonial Uganda and its culture. He described the estrangement and absence from African tradition left behind by colonialism. He construed the dis:connective relationship between tradition and modernity, between the indigenous and the foreign, as an identity crisis that a new African art of a ‘New Africa’ is facing. Moreover, Kabiito contributed artistic methods to the methodological discourse. Through art from Uganda, which is ‘a living modern art deeply rooted in tradition’, this absence and estrangement can be uncovered and overcome. Thus, artistic practice contributes to cultural decolonisation and functions as a method of dealing with absence and dis:connectivity. Kabiito connected art and research conclusively with a transdisciplinary method, one able to profoundly affect the culture of a ‘New Africa’. Gabriele Klein continued with a talk about The dancing body is absent/present. Methodological and theoretical aspects of digitalisation in dance. She described the approach to dance in dance studies as intrinsically dis:connected. Dance fades in its physicality after the performance. It seems simultaneously absent and present in the memories of the spectators, but it also appears transformed and present in other media. Questions about the absence of corporeality especially in relation to digital media pose epistemological problems for dance studies. Here, Klein focused on social media platforms such as TikTok, in which dance is represented in many forms and can be accessed globally. She proposed a praxeological method that respects the differences between dance and dance studies and includes the new, young generation of digitally influenced choreographers with a global reach. She concluded that digital media can partially overcome absences, but researchers need to reflect more than ever on their use of medium and methods. The ensuing discussion revealed changes in dance through digital and global social media. Contrary to the expectation that more possibilities for participation would flourish on digital media, Klein observed a standardisation of dance in the digital and thus a dwindling of diversity. Later, the artist Aleksandra Domanović spoke about cultural dislocation in her presentation From yu to me to turbo culture: presence and absence in internet technology and culture in the former Yugoslavia. The absence of a state that has dissolved with all its institutions but is present in the past of its former citizens results in a crisis of identity. They are simultaneously connected and disconnected to Yugoslavia and its culture. The identity crisis is especially apparent in the phenomenon of Turbo Culture, in which Yugoslavian architecture, public sculpture and cultural assets have been rapidly replaced by non-local structures. Thus, Turbo Culture erected monuments of Bill Clinton as well as Hollywood figures like Rocky Balboa in the former Yugoslavia. In her art, Domanović deals with these aspects of the disconnected and the absent. She sees her art as a means of pointing out this identity crisis marked by absence and dis:connectivity. Meha Priyadarshini then spoke about Fashion and its absent histories: the case of Madras fabric in the Caribbean. She notes aspects of absence in the history of Madras fabric, which colonial powers exported from India to Euro-American and African-diasporic markets. The importers never reflected on its foreign cultural heritage and traditional Indian origins. Madras fabric, with its specific colour and pattern, revolutionised the fashion industry but is dis:connected from its origins. To this day, the fashion industry is largely unaware of the origins of Madras textiles and profits uncritically from other cultures. The research of Madras fabric is complicated by this absence and dis:connectivity. No original Madras fabric has survived. Methodologically, Priyandarshini addressed this absence of historical consciousness through the open-access textile research project Subaltern Histories of Global Textiles: Connecting Collections. So, it is one aim to regrow historical connection of Madras textile to its origins, which could draw attention beyond academia to what patterns we wear our shirts and skirts. The first panel ended with the artist lecture by Parastou Forouhar and Cathrine Bublatzky. Bublatzky provided the theoretical framework and led the talk with her questions. Forouhar’s art deals with the absence and deracination of home. Her artwork Butterflies (2008) shows a butterfly collection, with each butterfly representing memories of her native Iran. The poetic encoding of memories of a changed homeland can thus be understood as an artistic method of facing absence and dis:connectivity. In her installation Written Rooms, Forouhar writes illegible Farsi texts with which Iranians are connected and disconnected at the same time; they are in familiar script but illegible nonetheless. The absences and dis:connectivity in relation to one's homeland thus become clear. Her art is a method of facing and experiencing absences and dis:connectivity. Sujit Sivasundaram opened the second panel on detours. He talked about Detours in the history of Islam in the Indian Ocean: Muslim Colombo. Originally a Muslim port city, Colombo has been a junction of cultural and economic connections for centuries. In such a globally connected city, the Muslim minority has been repressed, and their history has been erased since colonial occupation. Sivasundaram chose detours as a method of coming to terms with this marginalisation. Through the detour of material remains, such as architecture, clothes and artefacts, he explored the lives of minorities. The Colombo Grand Mosque served to demonstrate his method. Detour, as a methodological supplement, yields insights into dis:connectivity. Kerstin Schankweiler spoke about Global contexts of art in the GDR, in which detours played a decisive role. The German Democratic Republic (i.e. East Germany), where mobility was strongly controlled, opened up culturally to its so-called ‘brother nations’ via the detour of socialist internationalism. Bureaucracy and regulations extended this ideologically conditioned detour. Mail art, which overcame the Iron Curtain via the postal service, also dealt with dis:connectivity through postal diversions. The artistic relics of socialist internationalism and mail art depict detours as a way of dealing with dis: connectivity in the history of the GDR and in German-German history. Promona Sengupta talked about Time travel for all: decolonising the time-space continuum. She understands the idea of space that can be traversed and conquered as a colonial concept that shapes today's understanding. Similarly, Sengupta understands the linear concept of time as a colonial idea that supports capitalist productivity and is thus kept alive. These concepts lead to estrangement from the natural flow of space and time through colonialism and capitalism. New methods are needed to overcome them, methods that allow a non-capitalistic and non-colonial approach to space and time. Time travel, which reverses such understandings of time and space, is one example. In her conclusion, Sengupta recommended methods that question all-embracing concepts and open research to new perspectives. The lecture Rethinking urban materiality: time as a resource by Anupama Kundoo opened the third panel on the topic of interruptions. Her presentation revealed the interruptions in industrialisation, which replaced hitherto dominant local building traditions in local economies with local materials, with foreign experts and materials. Such changes actually reduce efficiency in many cases and uproot people from their buildings. Indeed, the building becomes a consumer in the global economy. She concluded by arguing for local industries and economies to create efficient architecture. Valeska Huber presented a paper entitled ´The Limits of my Language mean the Limits of my World´: language barriers and ideas of global communication in the 1920s, in which she reflected critically on English as a global lingua franca and thought about more inclusive alternatives to overcome linguistic barriers in global communication. Huber introduced the Vienna Circle of the 1920s, in which Maria and Otto Neurath, among others, developed Isotype, a pictorial language that is supposed to function across cultures and languages. Marie Neurath’s own projects were primarily responsible for Isotype’s global dissemination. Huber proposed that extending this idea could disrupt the Anglosphere and lead to more inclusive global communication and research. Thus, interruptions and dis:connectivity in global communication could be overcome. Peter W. Marx closed the panel by addressing The elephant in the room: (dis:)connecting encounters in the early modern period. Marx established dis:connectivity as the proverbial elephant in the room of global history studies. This was followed by a genealogy of the presence of elephants (and how it was documented by contemporary artists) in northern Europe from the Middle Ages to the early modern period. Marx’s genealogy showed historical interruptions and connections in the complex discourse around the elephants. From humanisation and fantasy to a symbol of power and violence, the discourse around elephants in Europe has also represented transcultural military and dialogical contact since Hannibal. Fabienne Liptay closed the conference with a screening of Atlantiques (2009, Mati Diop) and Atlantique (2019, Mati Diop). Across an interval of 10 years, the films deal with the topic of migration from Senegal across the Mediterranean to Europe. Characters meet their fates in transit. They are uprooted from their homeland and at the same time bound to it. Dis:connectivity is not just an abstract research topic, but it touches people's lives directly and concretely.Image: Ben Kamis

The speakers introduced new perspectives on dis:connective research on globalisation, including some methodological suggestions and approaches. Artistic practice uncovered dis:connectivity in several aspects, making it tangible and offering ways to deal with it. On a theoretical level, several participants emphasised the importance of critical reflection on one's own perspective and situatedness as a researcher. There were also proposals without a ripe, ready method, but set out demands, priorities and innovations for a methodology of global dis:connectivity. Indeed, this could be an initial step towards more developed methods. The ‘elephant in the room’ was certainly methodology. The dialogue and interplay between art and research invigorated the conference, resulting in a special climate of interdisciplinarity and multi-perspectivity. Minds open to novelty and awareness of the lack of a full-fledged methodology are a fine basis for further research. Facing this elephant in the room was perhaps one of the main achievements of the conference. Continue ReadingThe global dis:connect team.

21 March 2023

Ayala Levin's master class (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger)

Ayala Levin's master class (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger) The gd:c summer school takes a field trip to the Museum Fünf Kontinente. (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger)

The gd:c summer school takes a field trip to the Museum Fünf Kontinente. (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger) One, yet many (but not too many). (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger - the author in the back left with the snappy Hawaiian shirt)

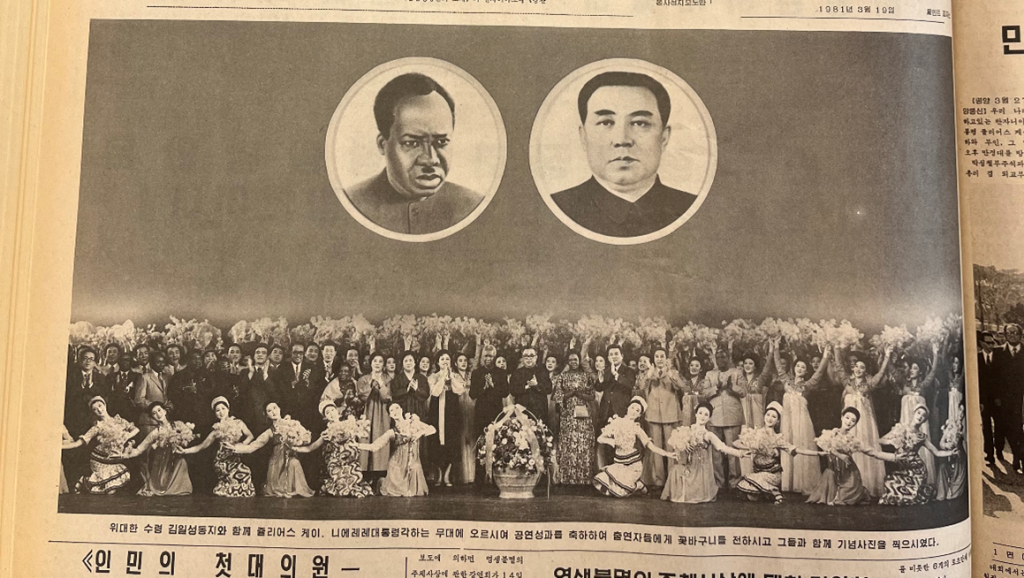

One, yet many (but not too many). (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger - the author in the back left with the snappy Hawaiian shirt) Julius Nyerere and Kim Il Sung congratulating the actors and actresses after watching a musical <Song of Paradise> in Mansudae Art Theater (Rodong Shinmun March 28, 1981), photograph by the author.

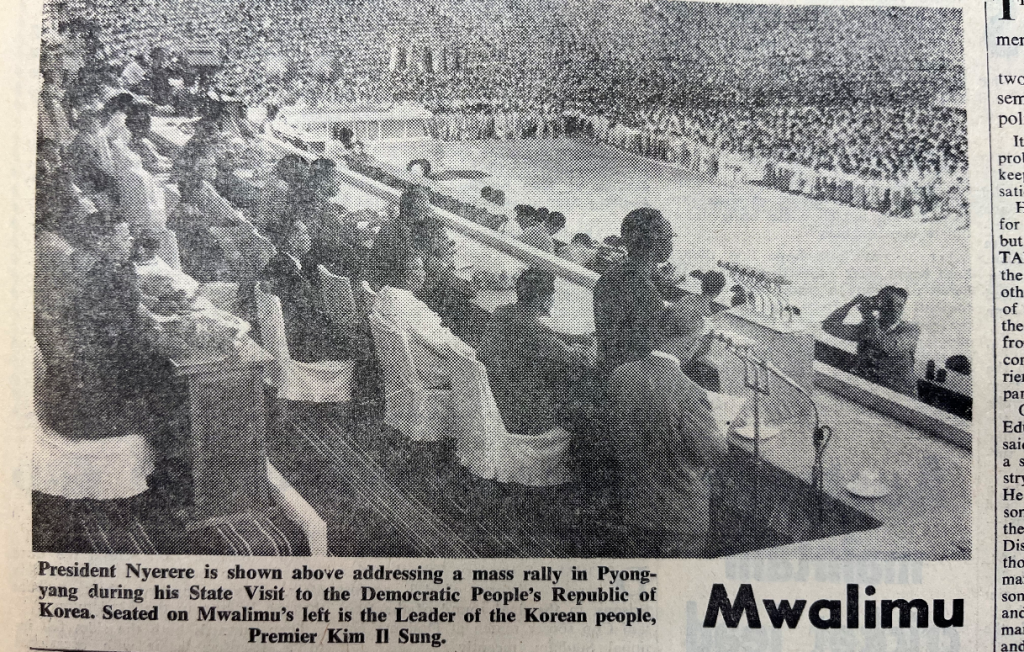

Julius Nyerere and Kim Il Sung congratulating the actors and actresses after watching a musical <Song of Paradise> in Mansudae Art Theater (Rodong Shinmun March 28, 1981), photograph by the author. Julius Nyerere addressing a speech in front of a mass rally in Pyongyang (The Nationalist, June 27, 1968), photograph by the author.

Julius Nyerere addressing a speech in front of a mass rally in Pyongyang (The Nationalist, June 27, 1968), photograph by the author.