In

Blog 2023

hanni geiger

[Editor's note: The adjective 'Islamic' was changed to 'Arab' for greater accuracy in a single instance on 11 September 2023.]

The ceramic works of Hanna Charag-Zuntz (1915—2007) in exhibitions throughout the world cannot be read in isolation from the nationally framed history of Israeli ceramics. The exhibition catalogues all address the creative and social connections between East and West in very different ways. Some exhibitions link the artist’s vases, pots and bottles to the themes of exile and imported European modernism as an influence on Israeli ceramics since the state was founded in 1948. This contrasts with exhibitions that link the objects as representatives of a new Jewish pottery (and identity) with archaeological finds in the Middle East and to the state’s demand for cultural assimilation and national stability. In the postmodern-oriented exhibitions, the works are presented as transcultural objects that distance themselves from the early Zionist premises of social unification, but the exhibitions’ frames hardly allow for any deviation.

As different as the programmes might appear, exhibitions framed or funded by national and/or religious institutions tend to conflate Orient and Occident. Favouring a state identity based on connection, these exhibitions and their catalogues fail to problematise the complex, politically charged entanglements of East and West.

By analysing three exhibitions and their catalogues with a local approach focused on the Levant, I decouple Charag-Zuntz’s ceramics, mainly created in the 1950s—70s, from national narrative patterns of abbreviated connections between East and West.

[1] Drawing on Levantine cultural philosophy — a social concept linked to the Eastern Mediterranean — my aim is to reveal the artistic and social interruptions and absences that are usually blurred in nation-based frames.

I work with the concept of dis:connectivity, which emphasises the simultaneity and dynamic co-constitution of integrative and disintegrative elements in globalisation processes, which only become relevant in relation to each other.

[2] I argue that the vessels, which were made on the shores of the eastern Mediterranean, should be interpreted relative to a dis:connective body of water and its local cultures. This means reading the objects in connection to a Levantine Mediterranean — a reading that contradicts geopolitical narratives as presented in the catalogues and as known from theories of the Mediterranean.

[3] Although these theories survey many definitions of this sea and recognise the significance of regional cultures and fragmentations, they all emphasise connectivity, which — whether conceived nationally or otherwise — ultimately produces a certain degree of temporal and spatial stability as well as homogeneity.

[4] What remains absent in such representations is the predominantly North-Western perspective on the narrated Mediterranean and the structurally conditioned, asymmetrical relationship between the narrow ideas of the sea and its creators.

Recontextualising these objects in terms of a ‘Levantine Sea’, which appears unifying and stable only in terms of its physical characteristics and is in fact socially marked by ambivalent connections that coincide with migration, unbounded and fluid identities, constant change and subversion,

[5] would mean recognising these characteristics as intrinsic to Charag-Zuntz’s work. Relating the forms, colours, materials and techniques of her pieces to Mediterranean dis:connectivities could reveal past and present hegemonic structures that feign connectivity.

In order to disrupt the nationally constructed narratives, it is necessary to allow for other perspectives and agencies. I analyse the formal properties of the ceramics through a contemporary Mediterranean lens and reveal what these objects communicate when read as creations not only of the artist, but also of the sea and its coast. Doing so yields insights as to what objects connected to a specific locality but that elude anti-territoriality can tell us about design and ultimately about society. It uncovers how objects that are materially and narratively immobilised in exhibitions but that are in a constant state of cultural performativity tell stories about heterogeneity and entanglements as well as discrimination and exclusion. It describes how the Mediterranean relates to the global North and West or Europe. And it demonstrates how dis:connective objects help to reframe the sea and contribute to thinking globalisation from the eastern and southern Mediterranean.

On becoming one: harmonising East-West disconnections

A photo from the online exhibition

Ton in Ton. Jüdische Keramikerinnen aus Deutschland nach 1933 at the Jewish Museum Berlin in 2013 shows the young Charag-Zuntz in Siegfried Möller’s studio (fig. 01), where she apprenticed in pottery, before she fled to Palestine in 1940.

[6] At the wheel, she is shaping an object with a narrow base and voluminous belly that tapers toward the opening. In its simplicity and progressiveness, the piece can be associated with the Bauhaus, to which Charag-Zuntz was indirectly exposed.

[7]

The influence of exile, the design teachings from Germany and their imputed superiority over Middle Eastern material, techniques, forms and designs are evident in the text accompanying the exhibition.

[8] In it, Michal Friedlander describes the confluence of the East and West in the foundation of Jewish craft, but at the same time allows for criticism of the inhospitable geographic environment and the limitations of indigenous Arab pottery. Although following a long tradition, and though early Israeli ceramic production also draws on the knowledge of Arab potters and collaboration with them, the text depicts ‘underdeveloped Palestine’, with its aridity and heat that prohibited Western glazes, tints and kilns, as an impediment to the establishment of serious ceramic art in Israel.

Nevertheless, according to Friedlander, Charag-Zuntz succeeds in fusing European purism with Middle Eastern experiments with clay, resulting in a seemingly universal aesthetic. This creative connection of purportedly universal validity can be read as a reference to the social unity and stability to which the newly founded nation of Israel aspired. In fact, though, it was caught between cultures. This exhibition, like numerous others, effaces the tensions that attended the simultaneous selection and rejection of West and East in society and the arts.

The exhibition

Forms from Israel, sponsored by the Government of Israel in cooperation with the America-Israel Cultural Foundation & Crafts From Israel, and shown at the New York Museum of Contemporary Crafts, chose a different context for Charag- Zuntz’s objects as mediators among the cultures of Israel exactly a decade after its founding in 1948.

[9] Under the heading

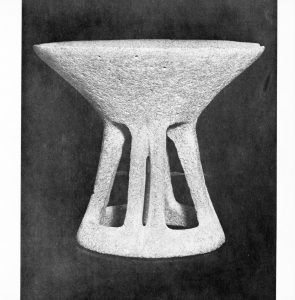

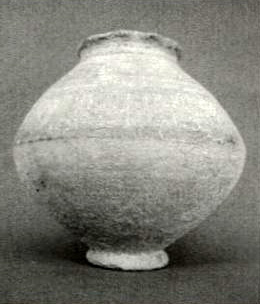

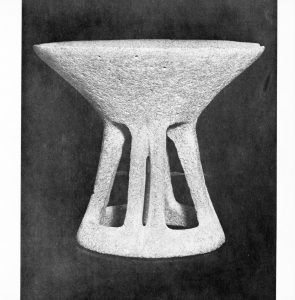

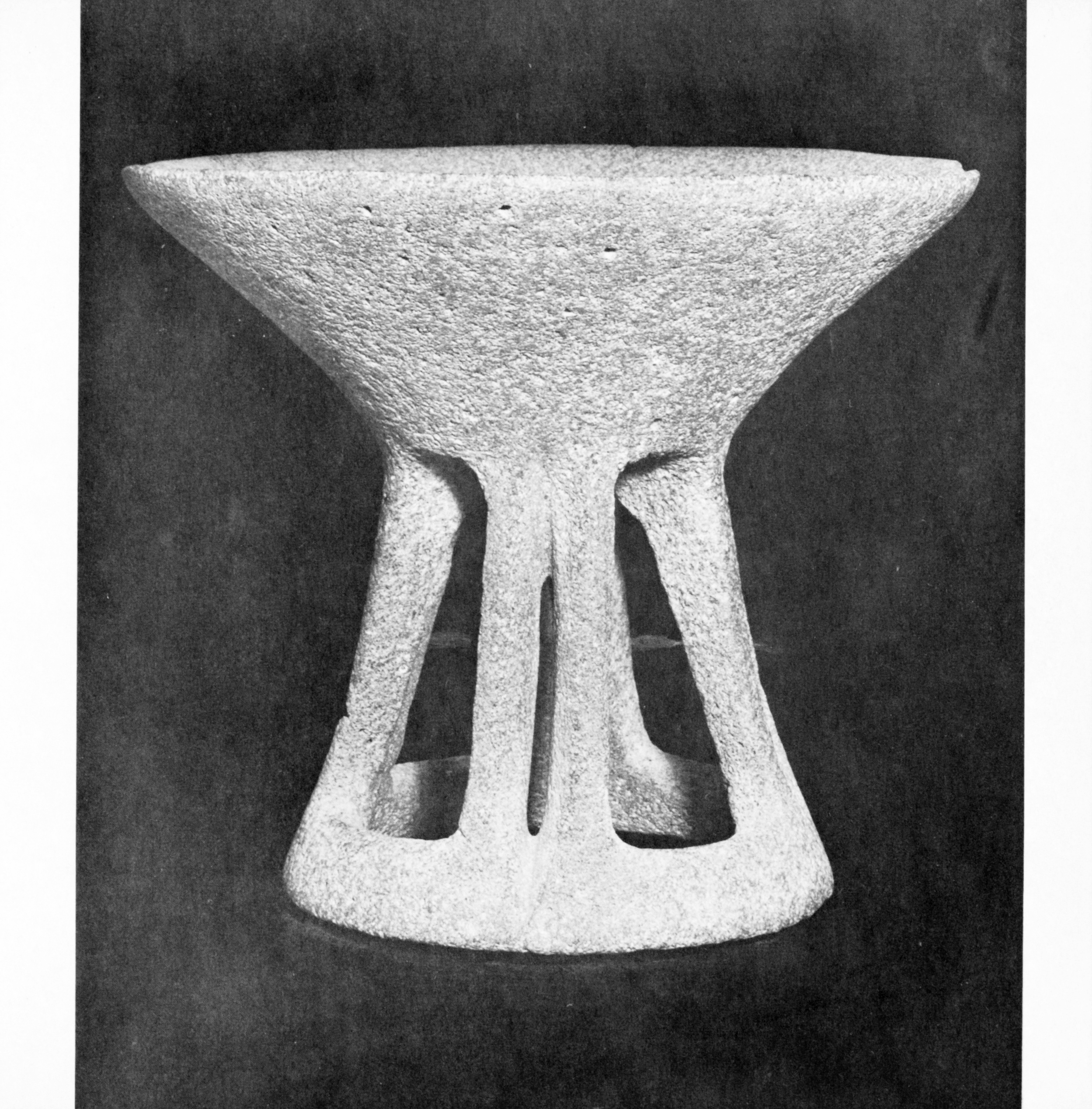

Continuities, her works are flanked on the following page of the accompanying catalogue by a basalt bowl from the biblical site of Beersheba dating to 4000 BCE (fig. 02a + 02b).

[10]

Fig. 02a: Hanna Charag-Zuntz, various ceramic vessels, undated.

Fig. 02b: Basalt bowl, Bersheeba, 4000 BCE

(© American Federation of Arts /

Courtesy American Craft Council

Library & Archives).

Despite a certain formal resemblance between the longer vessel shown here and the early pieces she had created in Germany (see fig. 01), the narratives about her objects in this exhibition, which celebrates the formation of Israeli identity, focus less on European modernity than on the archetypes of the territorially delimited landscape of the Middle East. The juxtaposition of contemporary Israeli handicrafts and purportedly Jewish-Canaanite archaeological finds in the catalogue is intended to emphasise the continuity of biblical Palestine and to restore its authenticity, which had been thought lost.

[11] Additionally, the ‘renascence of a Hebrew civilisation’ is linguistically affirmed by employing the words ‘convergence’, ‘mixing’ and the ‘melting pot’ of carefully selected cultural elements.

[12] This hybridisation of particular set pieces — traditional and contemporary — is noticeable in the juxtaposition of Turkish coffee sets, Arab drums, poster design and modern wooden toys.

Charag-Zuntz’s work here is marshalled to reinforce a national ceramic tradition based in multicultural assimilation of excavated finds as markers of genuine Jewish culture and diverse immigrant cultures into the Middle Eastern landscape. What remains invisible, however, is a fusion restricted to selected art pieces, styles, elements and cultural groups.

[13] As Rachel S. Harris argues, connecting with the new landscape economically and physically meant simultaneously remaining intellectually and socially distinct from the Middle Eastern ‘Other’. The catalogue erases the exclusion of any unreformed groups, namely Muslim communities, Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews, that blurred identities and disrupted hybridisation.

My next example is the 2018 exhibition in San Diego, entitled

Israel. 70 Years of Craft and Design, that reckoned with the Zionists’ previously lauded notions of hybridisation. According to the catalogue’s authors: ‘[…] it did not result in forming the collective unified identity of the “New Jew” dreamt of by Israel’s first leaders. Instead the Israeli melting pot sizzled with a vast array of ideologies, vigorously contradicting and swiftly replacing one another but never cohering into one entity’.

[14] The exhibition was a collaboration between the House of Israel, which professes emphatically to be ‘non-profit’, ‘non-political’ and ‘non-sectarian’ at the beginning of the catalogue, and the Mingei international Museum, whose programme is dedicated to the collection, preservation and exhibition of arts of daily life ‘from all eras and cultures of the world’.

[15]

Although the catalogue distances itself from Israel’s early policy of unification, the exhibition recalls

Form from Israel. It includes a selection of diverse objects from different times and cultures that have shaped Israel. Traditional Bedouin textiles and Yemeni jewellery were shown alongside contemporary industrial products, furniture and ceramics, notably Charag-Zuntz’s.

[16] In contrast to what the museum claims on its webpage, the objects do not ‘[…] speak for themselves — in line, form, and color — the universal language of art’.

[17] Instead, they are contextualised by Smadar Samson’s introduction, who relates the multidisciplinarity and stylistic heterogeneity of the vessels to a pluralistic Israel, open to differences and deviations. But, by emphasising the connection of diverse creative set pieces within one object — without referring to social gaps, segregation and isolation — the objects are once again truncated as symbols of cultural reconciliation,

[18] at which point we must return to the exhibition’s title. The artefacts are employed to commemorate the founding of a state that geopolitically subsumes its cultures, religions and languages under an all-encompassing category. The curators’ critique of Israel’s unity policy and the museum’s pacifist programme thus seem committed to an imaginary postmodern dissolution of artistic and social classifications that never manifests in (national) reality.

Levantine disruptions or detours to connection

The émigré and philosopher Vilém Flusser observed that ‘visual languages’ ‘[…] run across the boundaries of national languages […]’.

[19] So what do Charag-Zuntz’s ceramics reveal when decoupled from geopolitical narratives? What happens when we focus instead on their formal properties from a local perspective that would, unlike previous exhibitions, view the Mediterranean as the objects’ co-designer?

Upon moving to Haifa in 1943, Charag-Zuntz specialised in Terra Sigillata, an ancient Mediterranean technique.

[20] In this process, the pieces are fired at high temperatures and usually obtain a shimmering red surface without glazing. This technique was practiced throughout the Mediterranean 2500 years ago and suggests that people and their products were moving across historical and political boundaries.

[21]

Nationally framed exhibitions mention Terra Sigillata in Charag- Zuntz’s work as one of her many design tools. These exhibitions invoke this technique to symbolise Israel’s unitary ideal of interconnected cultures. In the context of the philosophy of Levantinism, however, the objects’ core message changes.

‘Levantine’ stands for a diverse society of immigrants from different places in the Mediterranean, including descendants of Genoese and Venetian merchants and of Jews who fled to the Ottoman Empire from Spain since antiquity.

[22] They are migrants, refugees and dissidents who mixed with other minorities in the coastal countries of the eastern Mediterranean: Christian Arabs, Greeks, Armenians and Jews. Marked by their place of arrival rather than their origins, even Jewish immigrants from North Africa and Arabic groups were called Levantines. They were branded as non-conformist, partly Eastern in the West and partly European in the East, subject neither to the colonial dictum of imitating the West nor to the later Israeli orientation towards Europe.[23] This diverse group of people were perceived as a threat to national identity and security, presumably because they were ‘not all of a piece’ and refusing to be ‘contained’ in geopolitical categories.[24] In their territorially and culturally indeterminate existence on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean, as ‘cross-breeds’ despised by Israel’s early assimilating forces,

[25] they de-stabilised territories and interrupted political narratives of connection.

Prompted by the politically negated diaspora and the collective memory of Jews of European and Arab origins in the 1950s and 60s, Jaqueline Kahanoff dared to revitalise Levantinism as a social option for the young state.

[26] In a 1959 article entitled

Israel: Ambivalent Levantine, she called for a transcultural society that would include Arab and other minorities on an equal footing.

[27] She referred to the absence of all the rejected, discriminated and geographically and socially excluded groups in slums, refugee camps of the Occupied Territories and marginal development town,

[28] especially those marked by centuries of migration along the eastern Mediterranean coastline, which actually means half the population of Israel.

[29]

Linking Charag-Zuntz’s objects to the contested waters off Israel’s coast exposes ambiguities and tensions that are constitutive of social entanglements. It reveals constant change, disturbing expectations of rootedness that coincide with residence and indicating the simultaneous identification with and disavowal of both East and West. In short, it subverts spaces and disrupts singularities.

[30] Also, the vessels narrated through this Mediterranean-Levantine lens disclose absences caused by the (neo-)colonial and imperialist programme of connections limited to selected decorative facets

[31] of the Middle East that become equally evident in most exhibitions of Charag-Zuntz’s pieces. The narratively excluded elements of the cultural ‘Other’ remain invisible. Therefore, the works’ interruptions and absences in form and content demand interrogation.

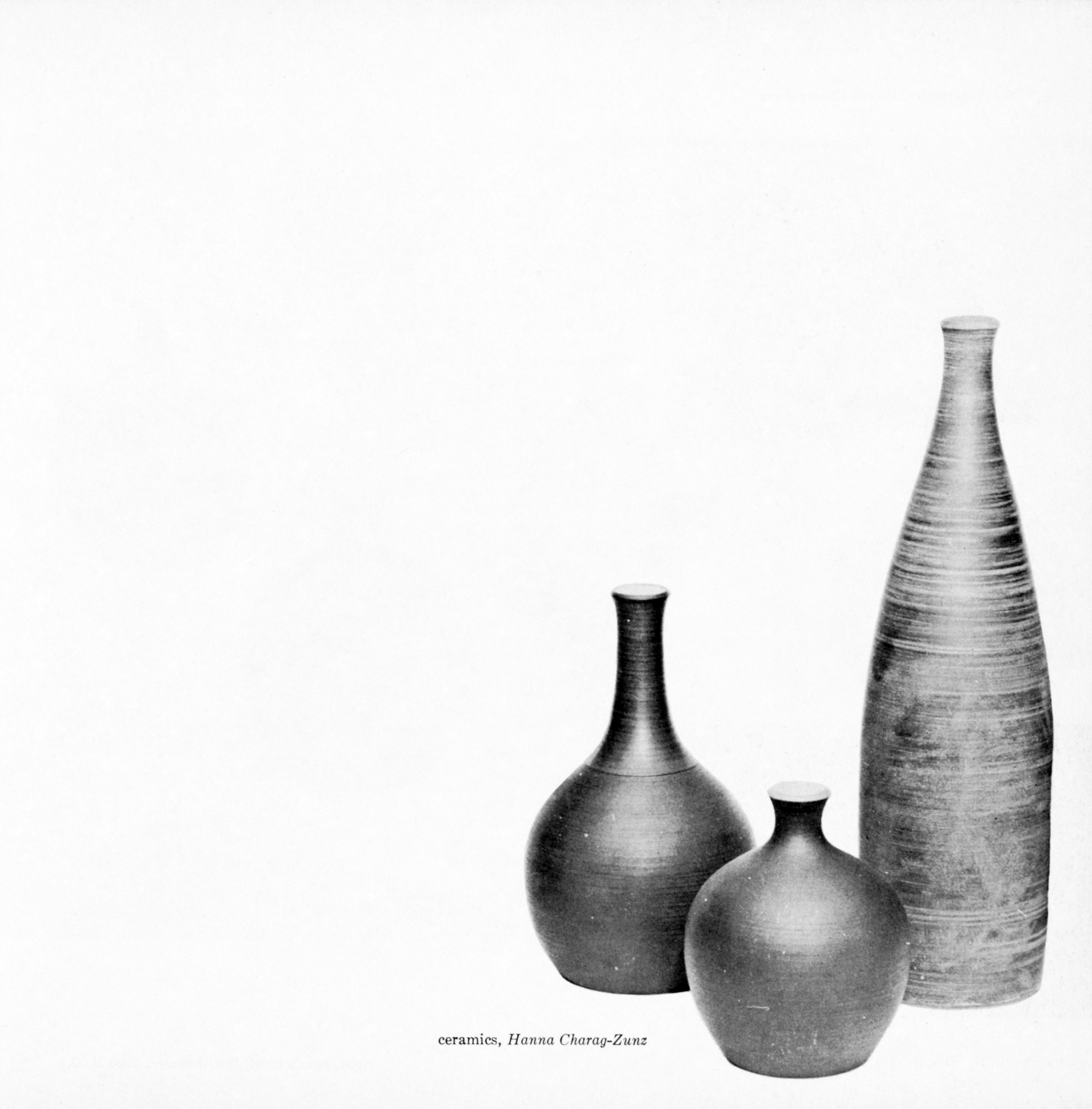

This becomes evident not only in Charag-Zuntz’s use of Terra Sigillata, which is a politically discarded symbol of cultural non-fixation and ambivalence in the eastern Mediterranean, but also through the ceramic’s shadings (fig. 03). Apart from the numerous reddish, yellow and brown objects, such as those in

Forms from Israel, she also uses turquoise, blue and green nuances, which the exhibitions omit and fail to associate with the Oriental and Mediterranean ceramics known for these hues.

[32]

Fig. 03: Hanna Charag-Zuntz, various ceramic vessels, late 1960s and 1970—’76s, image: Shay Ben Efraim (© The Benyamini Contemporary Ceramics Centre / © Shay Ben Efraim).

The absence of the ‘Other’ in design also becomes apparent in the objects’ material. Charag-Zuntz finds sand and brine for the firing process off the ‘impure’ coast of Israel and clay in the formerly Arab Negev Desert, since absorbed into Israel.

[33] This becomes relevant considering that the ascendence of Israeli ceramics and their national promotion to the status of art rests on the allegorical creation of ‘Adam’ and ‘Adamah’, referring to Israeli society, which actually arose from local — most recently Muslim — earths.

[34]

The catalogues’ description of the vessels as predominantly ‘calm’, ‘clear’, ‘simple’, ‘balanced’ and ‘unifying’ is also disputable.

[35] In contrast to the exhibitions, one could equally focus on the tension between the pots’ protruding bellies and narrow openings, which interrupts Israeli rhetoric of cultural harmonisation. The objects’ doubtful functionality, which is a product of this formal disparity, further reinforces the impression of disruption: as in design, so in society.

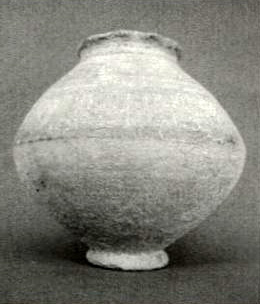

The references some exhibitions make to ostensibly Jewish archaeological finds can also be disrupted. Round artefacts with shapes that merge almost seamlessly into the opening and elongated forms that expand in the middle are also found among Levantine cultures from Cyprus and Muslims from Syria and Palestine (fig. 04a + 04b).

[36] Moreover, the horizontal lines are also a common design element in ancient Levantine ceramics.

[37] Charag-Zuntz’s brushstrokes, interpreted as Japanese in some exhibitions,[38] exemplify such Levantine characteristics.

Fig. 04a:

Jar with geometric designs, Levantine, ca. 585 BCE, h. 10,2 cm, terracotta, The William D. and Jane Welsh Collection at Fordham University, (from: Barbara Cavaliere and Jennifer Udell, eds., Ancient Mediterranean Art. The William D. and Jane Welsh Collection at Fordham

University (New York: Fordham University Press, 2012), 334.)

Fig. 04b

Bottle with pouring spout for water transport, mid-4th millennium BCE, Habuba Kabira, Syria, clay, pottery wheel ceramics, h. 69 cm, Prähistorische Staatssammlung, München, inv. nr. 1985, 701; (from: Gisela Zahlhaas, Prähistorische Staatssammlung. Keramiken des Vorderen Orients im internationalen Keramik-Museum Weiden, collection catalogue, Weiden, Keramik-Museum, 1990, 65.)

Thus, if we consider Charag-Zuntz’s works to be shaped by the eastern Mediterranean, a double dis:connectivity emerges. First, the detachment of the vessels from national narratives and their simultaneous coupling with a Levantine local culture is a methodological dis:connectivity, which reveals absent maritime narratives. Second, these maritime narratives frame the pieces as products of complex connections that go along with interruptions and absences. They are bound to a specific location but subvert the ideas of a settled territory and singular religions, languages and identities; they perform culture without possessing it.

[39] A ‘neither—nor’ supplants and interrupts the narrow national vision of a ‘both—and’.

[40] Interpreting the objects through this local cultural lens exposes the politically constructed absences that the nationally framed narratives of the exhibitions manage to circumvent. Instead of connection, harmony, and stability, analysing the works through an expanded Levantine perspective unveils past and present hegemonic mechanisms that segregate and exclude unwanted groups. The objects testify to the multidimensional interconnections in a space whose natural characteristics seem stable, all-encompassing and unifying, but whose social and political changes connote instability. These pieces echo the understanding of globalisation Deleuze and Guattari described as ‘[…] an effect of the multitudes of forces that coalesce, concatenate, and collapse at local, provisional sites.’

[41]

In this light, the Mediterranean and the understanding of the ceramics produced along its shores are more complicated than most theories (and exhibitions) permit. By revealing the interruptions and absences — in research and society — dis:connected objects read in contemporary Levantine terms present an alternative to the simplistic rhetoric of national connectivity. Extending the point, this new perspective and the visualisation of excluded artefact narratives and groups can even reintroduce previously erased themes and agents in art and society. For the history of art, craft and design, regionally influenced approaches can complicate object-bound narratives by generating more creative, institutional and personal participation and contribute to non-hegemonic research and theorisation. Locally framed objects represent a detour to a social and artistic presence and inclusion that national narratives only imagine.

By extension, dis:connective Mediterranean artefacts could interrupt the dominant Northern and Western narratives of the Mediterranean, de-nationalising its past for its future perception.

[42] New (trans-)local perspectives, images, ideas and representations would help to reconceive the global impact of the Mediterranean and the discursive absences of the manifold influences, which it has always exerted on modern Europe and its identity.

[1] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the term ‘narrative’ goes back to the postmodern philosopher Jean-François Lyotard, who used it 1979 in La condition postmoderne to refer to a crisis that for him heralded an era succeeding optimistic modernity, when the meta-narratives of the Enlightenment and Idealism had become implausible. Recognising and naming a narrative as such thus means distancing oneself from it. In the social sciences of the last three decades, the term ‘narrative’ stands for ’meaningful storytelling’: as regionally, culturally or nationally related narratives that are subject to change and are imbued with legitimacy. In my investigation, I refer to both concepts and use the term critically to denote how storytelling can influence the way the environment and thus art and design are perceived. In the following, the term relates to the creation of meaning in Charag-Zuntz’s objects in the context of nationally framed exhibition catalogues on the one hand and the cultural concept of ‘Levantinism’ — a sort of counternarrative to the catalogues — on the other. See: ‘Narrativ’, Duden, 2023, https://www.duden.de/rechtschreibung/Narrativ_Erzaehlung_Geschichte; Matthias Heine, ‘Hinz und Kunz schwafeln heutzutage vom “Narrativ”’, Die Welt, 13 November 2016, https://www.welt.de/debatte/kommentare/article159450529/Hinz-und-Kunz-schwafeln-heutzutage-vom-Narrativ.html; Wolfgang Seibel, ‘Hegemoniale Semantiken und radikale Gegennarrative. Beitrag zum Arbeitsgespräch des Kulturwissenschaftlichen Kollegs’, Uni Konstanz, 22 January 2009, https://www.exc16.uni-konstanz.de/fileadmin/all/downloads/veranstaltungen2009/Seibel-Heg-Semantiken-090122.pdf.

[2] This concept was coined by the Käte Hamburger Research Centre global dis:connect, see: ‘Research’, global dis:connect, 2023,

https://www.org/research/disconnectivity/.

[3] Among the basic theories of the Mediterranean are: Fernand Braudel,

La Méditerranée et le Monde méditerranéen à l’epoque de Philippe II (Paris: Armand Colin, 1949); Peregrin Horden and Nicholas Purcell,

The Corrupting Sea. A Study of Mediterranean History (Oxford: Blackwell, 2000).

[4] See Braudel’s study on how the geographical and cultural consistency and uniformity of the Mediterranean has affected humanity and our perception of the natural Connectivity — a concept later adapted by Horden and Purcell — plays a major role. Although the latter refer to the fragmented nature of the micro-regions, the natural disposition of a larger inland sea implies a bond and an exchange that ultimately ensures unity in diversity — which is once again elevated to the specificity of the Mediterranean. See: Braudel,

La Méditerranée et le monde méditerranéen; Horden and Purcell,

The Corrupting Sea; Mihran Dabag et al., ‘“New Horizons” der Mittelmeerforschung. Einleitung’, in

New Horizons. Mediterranean Research in the 21st Century, eds. Mihran Dabag et al., Mittelmeerstudien, 10 (Paderborn: Fink/Schöningh, 2016).

[5] Rachel S. Harris, ‘Israel. Finding the Levant within the Mediterranean’, review of

The Place of the Mediterranean in Modern Israeli Identity by Alexandra Nocke,

The Levantine Review, no. 1 (Spring 2012): 107-8.

[6] Jüdisches Museum Berlin.

Ton in Ton. Jüdische Keramikerinnen aus Deutschland nach 1933. Online exhibition 2013, Google Arts and Culture, 2013,

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/IQVBfUHgPN-sLA?hl=de.

[7] Even though Charag-Zuntz, like colleagues of hers, such as Hedwig Grossmann, had not attended the famous art school, she attests in an interview with Antje Soléau to growing up in ‘the artistic atmosphere of the Bauhaus’ and emphasises its tangible influence on the ceramic attitudes of the young ceramicists in Germany in the Cf.: Antje Soleáu, ‘Zwei Leben — Zwei Schicksale: Margarete Heymann-Loebenstein und Hanna Charag-Zuntz’,

Neue Keramik, no. 1 (2016): 33.

[8] For the following paragraph see: Michal Friedlander, ‘Vasen statt Milchflaschen — Eva Samuel, Hedwig Grossmann und Hanna Charag-Zuntz: Die Töpferpionierinnen in Palästina nach 1932’, in

Avantgarde für den Jüdische Keramikerinnen in Deutschland 1919—1933. Marguerite Friedlaender- Wildenhain, Margarete Heymann-Marks, Eva Stricker-Zeisel, Berlin, Bröhan- Museum, 2013, 104–11. Exhibition catalogue,

https://www.jmberlin.de/sites/default/files/katalogbeitrag_friedlander_0.pdf.

[9] The Israel Institute of Industrial Design in consultation with The American Federation of Arts, eds.,

Forms from Israel, New York, Museum of Contemporary Crafts in New York City, 1958–1960. Exhibition catalogue,

https://digital.craftcouncil.org/digital/collection/p15785coll5/id/4735/rec/2.

[10] Ibid., 44ff.

[11] Friedlander, ‘Vasen statt Milchflaschen’, 108-9. On roots of Jewish pottery in ancient Canaanite finds, see: Gidon Ofrat, ‘The Beginnings of Israeli Ceramics’,

Ariel 90 (1992): 79. The authors of the exhibition catalogues largely dismiss the influence of the ‘small’ and ‘little’ Arab pots, especially since they produced the porous earthenware disdained by German ceramists. Cf.: Soleáu, ‘Zwei Leben — Zwei Schicksale‘, 33.

[12] The Israel Institute of Industrial Design et. al.,

Forms from Israel, 6-7.

[13] For the following paragraph see: Harris, ‘Israel’, 106–11.

[14] Samson Smadar, ‘Introduction’, in

70 Years of Craft and Design, Mingei International Museum, 2018—2021, ed. Jean Patterson, San Diego, House of Israel, 2018, 12-13. Exhibition catalogue.

[15] Jean Patterson, ed.,

70 Years of Craft and Design, San Diego, Mingei International Museum, 2018—2021, San Diego, House of Israel, 2018, exhibition catalogue. Mingei International Museum, ‘About: Mission and Vision,’ accessed 9 February 2023.

https://mingei.org/about/mission.

[16] Patterson,

Israel, 92ff.

[17] Mingei International Museum, ‘About’.

[18] Patterson,

Israel, 92-3.

[19] Vilém Flusser, ‘Nationalsprachen’, in

Von der Freiheit des Einsprüche gegen den Nationalismus (Hamburg: CEP Europäische Verlagsanstalt, 2013), 12.

[20] The term dates to the 18th A name from antiquity is not certain. Cf.: Verena Hasenbach, ‘Terra Sigillata’, Historisches Lexikon, 31 December 2011,

https://historisches-lexikon.li/Terra_sigillata.

[21] Ofrat, ‘The Beginnings of Israeli Ceramics’, 87.

[22] For the following paragraph, see: Eva Meyer and Eran Schaerf, ‘Kahanoff’s Levantinism: The Anachronic Possibilities of a Concept’, BAK, accessed 3 February 2022,

https://www.bakonline.org/prospections/kahanoffs-levantinism-the-anachronic-possibilities-of-a-concept/.

[23] Jaqueline Kahanoff, ‘Reflections of a Levantine Jew’,

Jewish Frontier, April 1958, 7, cited in Meyer and Schaerf, ‘Kahanoff’s Levantinism’.

[24] Meyer and Schaerf, ‘Kahanoff’s Levantinism’; Harris, ‘Israel’, 107-8.

[25] Harris, ‘Israel’, 108.

[26] Jacqueline Shohet Kahanoff, ‘Ambivalent Levantine’, in

Mongrels or Marvels: The Levantine Writings of Jacqueline Shohet Kahanoff, Deborah A. Starr and Sasson Somekh (Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011), 193–212.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Karen Grumberg,

Place and Ideology in Contemporary Hebrew Literature (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2010), 243, cited in Harris, ‘Israel’, 116.

[29] Abraham B. Yehoshúa, ‘Beyond Folklore: The Identity of the Sephardic Jew’,

Quaderns de La Mediterrània, no. 14 (2010),

https://www.iemed.org/publication/beyond-folklore-the-identity-of-the-sephardic-jew-2/.

[30] Ronit Matalon,

The One Facing Us (New York: Metropolian Books, 1998), 214, cited in Harris, ‘Israel’, 116.

[31] Harris, ‘Israel’, 107.

[32] The objects were shown in an Israeli exhibition in 2019, which dealt with inter-generational dialogue among the artists. Cf.: Benyamini Contemporary Ceramics Centre,

Type of a Dialogue — Hanna Charag-Zuntz, Michal Alon, exhibition, Tel Aviv-Jaffa, 2019,

https://www.benyaminiceramics.org/en/ceramic-galleries/past-exhibitions/2019-2/type-if-a-dialogue/.

[33] Ofrat, ‘The Beginnings of Israeli Ceramics’, 76.

[34] From a quote by the ceramist Hedwig Grossmann-Lehmann on the beginnings of Israeli ceramics. Cf.: Maika Korfmacher, ‘Hanna Charag-Zuntz und Varda Yatom’, in

Hanna Charag-Zuntz und Varda Yatom. Gefäße und Skulpturen aus Israel, ed. Bernd Hakenjos, Düsseldorf, Hetjens Museum, 1998, 6. Exhibition catalogue.

[35] Ibid., 7, as well as Tadmor,

Tova Berlinski.

[36] For an overview of Levantine jars from the ancient Mediterranean region, see: Barbara Cavaliere and Jennifer Udell, eds.,

Ancient Mediterranean Art. The William D. and Jane Welsh Collection at Fordham University (New York: Fordham University Press, 2012). For Syrian or Palestinian traditional pottery, see: Gisela Zahlhaas,

Prähistorische Staatssammlung. Keramiken des Vorderen Orients im internationalen Keramik-Museum Weiden, (1990). Collection catalogue; John Landgraf and Owen Rye, ‘Introduction’, in

Palestinian Traditional Pottery. A Contribution to Palestinian Culture, eds. Elizabeth Burr et al. (Leuven/Paris/Bristol: Peeters, 2021), XXVII–XXX.

[37] Cavaliere and Udell,

Ancient Mediterranean Art, especially 334.

[38] For example, in the exhibition

70 Years of Craft and Design. Cf.: Patterson,

Israel, 92.

[39] Gil Hochberg, ‘“Permanent Immigration”: Jacqueline Kahanoff, Ronit Matalon, and the Impetus of Levantinism’,

Boundary 31, no. 2 (Summer 2004): 220–21, cited in Harris, ‘Israel’, 107.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guttari,

A thousand plateaus: capitalism and schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, First published 1980 by Éd. de Minuit, Paris), cited in: Cavan Concannon and Lindsey A. Mazurek, ‘Introduction: A New Connectivity for the Twenty-First Century,’ in

Across the Corrupting Sea: Post-Braudelian Approaches to the Ancient Eastern Mediterranean, eds. Cavan W. Concannon and Lindsey A. Mazurek (London: Routledge, 2016), 14.

[42] Matthew D’Auria and Fernanda Gallo, ‘Introduction. Ideas of Europe and the (Modern) Mediterranean’, in

Mediterranean Europe(s). Rethinking Europe from its Southern Shores, Matthew D’Auria and Fernanda Gallo (London/New York: Routledge, 2023).

Bibliography

Benyamini Contemporary Ceramics Centre,

Type of a Dialogue — Hanna Charag-Zuntz, Michal Alon. Exhibition, Tel Aviv-Jaffa, 2019.

https://www.benyaminiceramics.org/en/ceramic-galleries/past-exhibitions/2019-2/type-if-a-dialogue/.

Braudel, Fernand,

La Méditerranée et le monde méditerranéen à l’epoque de Philippe II. Paris: Armand Colin, 1949.

Cavaliere, Barbara and Jennifer Udell, eds.

Ancient Mediterranean Art. The William D. and Jane Welsh Collection at Fordham University. New York: Fordham University Press, 2012.

Concannon, Cavan, and Lindsey A. Mazurek, eds.

Across the Corrupting Sea: Post-Braudelian Approaches to the Ancient Eastern Mediterranean. London: Routledge, 2016.

Dabag, Mihran, Dieter Haller, Nikolas Jaspers and Achim Lichtenberger. ‘“New Horizons” der Mittelmeerforschung. Einleitung’. In

New Horizons. Mediterranean Research in the 21st Century, edited by Mihran Dabag, Dieter Haller, Nikolas Jaspers, and Achim Lichtenberger, Mittelmeerstudien, 10. Paderborn: Fink/Schöningh, 2016.

D’Auria, Matthew and Fernanda Gallo. ‘Introduction. Ideas of Europe and the (Modern) Mediterranean’. In

Mediterranean Europe(s). Rethinking Europe from its Southern Shores, edited by Matthew D’Auria and Fernanda Gallo. London/New York: Routledge, 2023.

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guttari,

A thousand plateaus: capitalism and schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987. First published 1980 by Éd. de Minuit, Paris).

Duden. ‘Narrativ’, 2023.

https://www.duden.de/rechtschreibung/Narrativ_Erzaehlung_Geschichte.

Flusser, Vilém, ‘Nationalsprachen’. In

Von der Freiheit des Migranten. Einsprüche gegen den Nationalismus, 11–14. Hamburg: CEP Europäische Verlagsanstalt, 2013.

Friedlander, Michal, ‘Vasen statt Milchflaschen — Eva Samuel, Hedwig Grossmann and Hanna Charag-Zuntz: Die Töpferpionierinnen in Palästina Nach 1932’. In

Avantgarde für den Alltag. Jüdische Keramikerinnen in Deutschland 1919—1933. Marguerite Friedlaender-Wildenhain, Margarete Heymann-Marks, Eva Stricker-Zeisel, 104–11. Berlin: Bröhan-Museum. Exhibition catalogue,

https://www.jmberlin.de/sites/default/files/katalogbeitrag_friedlander_0.pdf.

global dis:connect, ‘Research’, 2023.

https://www.globaldisconnect.org/research/disconnectivity/.

Google Arts and Culture,

Jüdisches Museum Berlin. Ton in Ton. Jüdische Keramikerinnen aus Deutschland nach 1933, online exhibition, 2013.

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/IQVBfUHgPN-sLA?hl=de.

Grumberg, Karen,

Place and Ideology in Contemporary Hebrew Literature. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2010.

Harris, Rachel S., ‘Israel. Finding the Levant within the Mediterranean. Review of

The Place of the Mediterranean in Modern Israeli Identity by Alexandra Nocke,

The Levantine Review, no. 1 (Spring 2012): 106–17.

Hasenbach, Verena, ‘Terra Sigillata’.

Historisches Lexikon, 31 December 2011.

https://historisches-lexikon.li/Terra_sigillata.

Heine, Matthias, ‘Hinz und Kunz schwafeln heutzutage vom “Narrativ”’.

Die Welt, 13 November 2016.

https://www.welt.de/debatte/kommentare/article159450529/Hinz-und-Kunz-schwafeln-heutzutage-vom-Narrativ.html.

Hochberg, Gil, ‘“Permanent Immigration”: Jacqueline Kahanoff, Ronit Matalon, and the Impetus of Levantinism’.

Boundary 31, no. 2 (Summer 2004): 219–43.

Horden, Peregrin, and Nicholas Purcell.

The Corrupting Sea. A Study of Mediterranean History. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

Israel Institute of Industrial Design, The, in consultation with The American Federation of Arts, ed.

Forms from Israel. New York: Museum of Contemporary Crafts in New York City, 1958. Exhibition catalogue,

https://digital.craftcouncil.org/digital/collection/p15785coll5/id/4735/rec/2.

Kahanoff, Jacqueline Shohet, ‘Ambivalent Levantine’. In

Mongrels or Marvels: The Levantine Writings of Jacqueline Shohet Kahanoff, edited by Debora A. Starr and Sasson Somekh, 193–212. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011.

Kahanoff, Jaqueline, ‘Reflections of a Levantine Jew’.

Jewish Frontier, April 1958.

Korfmacher, Maika ‘Hanna Charag-Zuntz und Varda Yatom’, in

Hanna Charag-Zuntz und Varda Yatom. Gefäße und Skulpturen aus Israel, edited by Bernd Hakenjos, 6–8. Düsseldorf, Hetjens Museum, 1998. Exhibition catalogue.

Landgraf, John and Owen Rye, ‘Introduction’. In

Palestinian Traditional Pottery. A Contribution to Palestinian Culture, edited by Elizabeth Burr, Jean- Baptiste Humbert, Owen Rye and Hamed Salem, XXVII–XXX. Leuven/Paris/ Bristol: Peeters, 2021.

Matalon, Ronit,

The One Facing Us. New York: Metropolian Books, 1998.

Meyer, Eva and Eran Schaerf, ‘Kahanoff’s Levantinism: The Anachronic Possibilities of a Concept’. Prospections. Accessed 3 February 2022.

https://www.bakonline.org/prospections/kahanoffs-levantinism-the-anachronic-possibilities-of-a-concept/.

Ofrat, Gidon, ‘The Beginnings of Israeli Ceramics’.

Ariel 90 (1992): 75–94.

Patterson, Jean,

Israel. 70 Years of Craft and Design, San Diego, Mingei International Museum, 2018—2021. San Diego: House of Israel, 2018. Exhibition catalogue.

Seibel, Wolfgang. ‘Hegemoniale Semantiken und radikale Gegennarrative. Beitrag zum Arbeitsgespräch des Kulturwissenschaftlichen Kollegs Uni Konstanz.’ Konstanz, 2009.

https://www.exc16.uni-konstanz.de/fileadmin/all/downloads/veranstaltungen2009/Seibel-Heg-Semantiken-090122.pdf.

Smadar, Samson, ‘Introduction’. In

Israel. 70 Years of Craft and Design. Mingei International Museum, 2018—2021, edited by Jean Patterson, San Diego, House of Israel, 2018. Exhibition catalogue.

Soleáu, Antje, ‘Zwei Leben — Zwei Schicksale: Margarete Heymann- Loebenstein und Hanna Charag-Zuntz’.

Neue Keramik, no. 1 (2016): 30–33.

Yehoshúa, Abraham B. ‘Beyond Folklore: The Identity of the Sephardic Jew’.

Quaderns de La Mediterrània, no. 14 (2010).

Zahlhaas, Gisela,

Prähistorische Staatssammlung. Keramiken des Vorderen Orients im internationalen Keramik-Museum Weiden. Collection Catalogue. Weiden: Keramik-Museum Weiden, 1990.

citation information:

Continue Reading