Yvonne Hackenbroch’s birdcage: the experience of Jewish exile and the return as object

änne söll

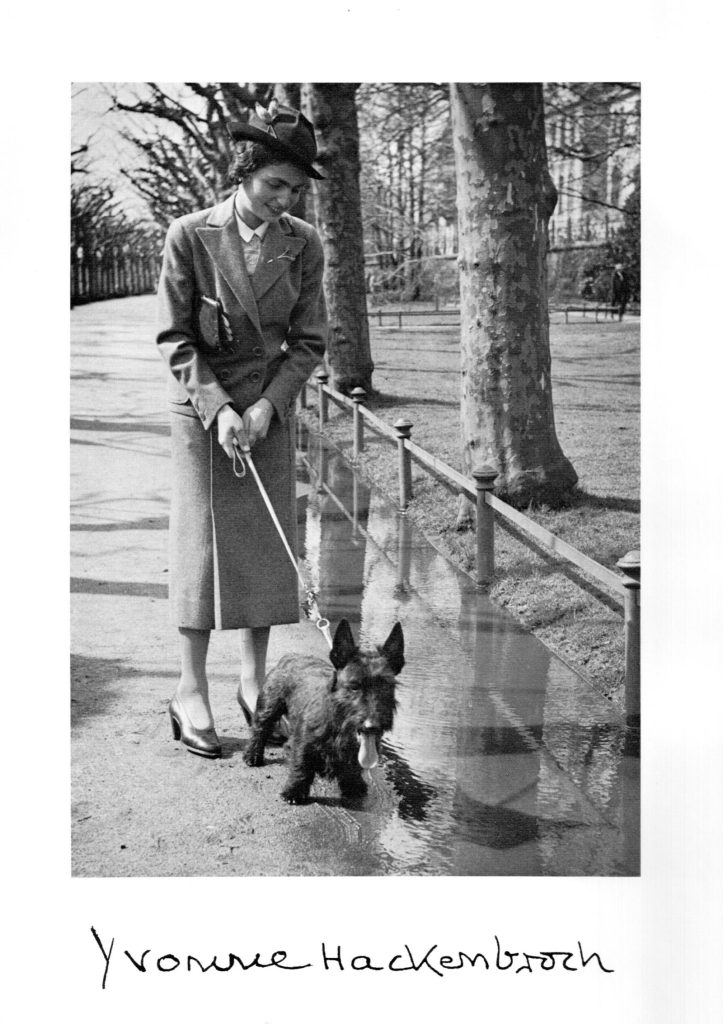

Fig 1: Yvonne Hackenbroch with family dog ‘Racker’, Frankfurt on the Main, c. 1935/36 (from: Jörg Rasmussen: Festschrift: Studien zum europäischen Kunsthandwerk, München 1983, cover).

Two years after receiving her doctorate from the University of Munich in 1936, the Jewish art historian Yvonne Hackenbroch (1912 – 2012) was compelled to leave Germany and emigrate to London in 1938, where her older sister and mother were already residing. Yvonne Hackenbroch’s father, a prominent and prosperous art and antiques dealer, had passed away the year before. This photo portrait shows Hackenbroch with the family dog ‘Racker’ (Rascal) in her native city, Frankfurt am Main, near her parents’ house in 34 Untermainkai. It is from this house, Yvonne Hackenbroch’s childhood home in Frankfurt, that the birdcage in question originates.

Fig. 2: Birdcage, 1757, 26.3 x 35.5 x 21.2 cm, carved, partly coloured and gilded oak and coniferous wood, metal wire covering, tray, Historisches Museum Frankfurt am Main, donated by Yvonne Hackenbroch 2012 (© Horst Ziegenfusz).

Hackenbroch took the cage with her to London. In fact, it accompanied her throughout her exile spanning decades. The two went first to Toronto, where she worked from around 1945 until 1949 as a curator for the Fareham Collection at the University of Toronto, then to New York, where she curated the Irwin Untermeyer Collection, even moving with the collection when it was relocated to the Metropolitan Museum. When she returned to London after her retirement in 1982, the birdcage was again among her belongings and remained in her apartment near Hyde Park until her death in 2012. At her behest, the wooden cage was then donated to the Historical Museum in Frankfurt as a ‘token of reconciliation[1]’ by her great-nephew Adam Hills. The cage is thus both a gift and a legacy. In its current presentation at the museum, as will become clear, it is as much a gesture of reconciliation as it is an object of admonition. The birdcage as museum object also produces a contradiction: it is simultaneously a symbol of incarceration as well as a reminder of Hackenbroch’s endurance and dignity in the face of persecution turning it into a truly dis:connected object.

With this bequest, Hackenbroch has (re-)inscribed herself and her displaced family into the history of the city of Frankfurt and sent what initially appears to be a reconciliatory message to the post-war generation. This gift can also be seen as the symbolic ‘return’ of Hackenbroch to the city of Frankfurt, which she had visited sporadically after the war, even delivering a lecture at the Historical Museum in 1990, but from which she was to remain permanently exiled, though it was the place she first called home.

Since incorporating the birdcage into its collection in 2013, the Historical Museum in Frankfurt has preserved it and, since 2017, displayed it not only in its permanent exhibit on the history of the city, specifically as part of the display on National Socialism, but also shown it online as an item in the digital collection. Within the museum, the birdcage thus leads a double life, for, as will become clear, its physical presentation in the collection and its presentation on the museum’s online platform are significantly different.

Bird/human/enlightenment: history, function and the symbolism of the cage

The birdcage presumably dates from 1757, as the year is emblazoned – prominently – along with Frankfurt’s eagle emblem on its front. Why the year 1757 was so conspicuously positioned on the front of the cage, however, remains a mystery.[2] 1757 is not connected with any significant event in Frankfurt’s history. Was the year an important turning point in the life of the person or family who owned it? A marriage or a birth perhaps? Or maybe it had not belonged to a family at all, and 1757 marks the founding of a bird breeders’ association? Was the date inscribed on the cage retroactively, or does it denote the year of its manufacture? It is also impossible to determine whether the cage is a family heirloom that had belonged to the Hackenbroch family since the 18th century. After all, her mother’s side had resided in Frankfurt from the late Middle Ages. Might the cage not have come from Zaccharias Hackenbroch’s antique business after all?

In short, there is no reliable information about the first 250 years of the birdcage’s ‘biography’. What is certain, however, is that the birdcage with its eagle, the emblem of the city of Frankfurt, reminded Yvonne Hackenbroch of her origins and that she valued the object immensely for that reason.[3] Thus, following Tilmann Habermas, the birdcage’s function for Hackenbroch was to integrate and symbolise her life story in exile.[4] In this way, the cage can also be called a Verlustsouvenir,[5] ‘a souvenir of loss’ that reminded Hackenbroch of the hometown that she had to leave behind and of her father, who most likely acquired it.

In addition to the imposing eagle on the outside, the cage also contained a bird: when it was delivered to the museum, there was a small wooden bird inside. It is not a mechanical songbird in a cage of the kind that was popular in the salons of the early 18th century, but a simple, modern wooden toy, likely manufactured in the 20th century. Its greenish-yellow colouring resembles a canary. It is, therefore, a ‘modern’ inhabitant of an ‘old’, richly decorated and stately birdcage.

In addition to its two bays, where the food dish and water bowl can be placed, the cage is made of partially gilded oak, softwood and iron rods.[6] Measuring 26cm x 25cm x 21 cm, the cage is quite small and was most likely intended for a delicate, domestic songbird or canary. Canaries had been bred in Tyrol as early as the 18th century and sold in large European cities by traders organised in guilds.[7] Birdcages of the 18th and 19th centuries featured a variety of designs from simple wood and wire models to elaborate, ornate versions made with costly materials.[8] This range indicates that bird keeping was a common activity across (almost) all social classes.

Small pets, such as dogs and squirrels and birds, grew increasingly popular in the 18th century as ‘luxury objects of the “better circles” and social climbers’.[9] Birds were thus ‘the means and locus of social distinction and the representation of power’.[10] They were relevant to the starkly segregated social classes for different reasons. The nobility kept birds for reasons of status, including falconry birds and expensive birds imported from overseas. Learned, bourgeois circles — largely men — were interested in birds as objects of study. Bourgeois women, on the other hand, kept birds as companions and amusements, sometimes training them.[11] In the course of the 18th century, according to Julia Breittruck, there was a ‘”bourgeoisification” of the bird. Songbirds were no longer just a noble, elite accessory, but became a bourgeois cultural asset.’[12] Especially in genre paintings of the 18th century, birds are more frequently depicted as the domesticated pets of bourgeois ladies. For example, in this painting by Jean Simeon Chardin, a lady plays a melody to her canary on a serinette — a small organ made especially for this purpose.

Fig. 3a Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin: La Serinette, also called Lady varying her amusements, 1751, 50 x 43 cm, oil on canvas, Musée du Louvre, Paris (© 2010 RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / René-Gabriel Ojéda).

Fig. 3b: Jean-François Colson: Portrait of the chemist Balthazar Sage, 1777, 100,5 x 81 cm, oil on canvas, Musée des beaux-arts, Dijon (© Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon/ François Jay, from: Julia Breittruck, Ein Flügelschlag in der Pariser Aufklärung, Zur Geschichte der Beziehungen zwischen Menschen und ihren Vögeln, Dortmund 2020, 64).

According to Julia Breittruck, the motif of the bourgeois lady with a bird she has trained was very popular in the mid-18th century. Breittruck sees this as enjoining bourgeois women to engage in the rearing not only of birds but also, of course, of their own children. In contrast to the aristocracy, bourgeois women were encouraged to see child-rearing as their intrinsically ‘female’ duty. The preoccupation with parlour birds was thus gender coded. While women were expected to educate, men were assigned the role of scientist, and their attention to birds became part of an experiment.

Pet birds also developed into objects of bourgeois entertainment for ‘convivial circles’ and in salons over the course of the 18th century. They became domestic companions, kept in the private rooms reserved for family and close friends.[13] Consequently, ‘domesticated birds became more and more the private leisure companions of their respective owners, even co-constituents of the kind and manner of private leisure’.[14] In paintings and prints, the bird functions, according to Julia Breittruck, ‘as the imagined and real double, the eyes and ears of its owner’. Hackenbroch’s birdcage, then, transports us to a time when songbirds had become a leisure activity of the middle classes and the object of scientific investigation and educational ambitions. So how did these factors impact museum’s presentation of its newly acquired object?

Semiophores: the twofold contextualisation of the birdcage in the museum

One of the fundamental tenets of museology is that objects stored or displayed in museums trade their original meaning and use value for a new one. They become what are known as ‘semiophores’,[15] a term coined by the Polish historian Krysztof Pomian to describe objects whose purpose, meaning or value is transformed with their relocation to the museum. In this vein, Hackenbroch’s birdcage loses its function as an 18th-century animal enclosure and the historical connotations discussed above. As a sort of ‘prison’, the old birdcage in the new context of the Historical Museum may allude to forced emigration and the ambiguous ‘freedom’ of exile. If we then see the wooden bird in the cage as representing the cage’s owner (and her persecuted family), we soon grasp the birdcage as a visual metaphor for the persecution of Jews in the Third Reich.

Fig. 4: Birdcage as shown within the Historische Museum Frankfurt’s permanent collection (© 2022 the author).

Hackenbroch’s cage, however, is not displayed in isolation but gains a special inflection from the objects around it, evoking a host of significations from which the historical background of 18th century fades entirely. Standing in the Historical Museum before the display case containing the birdcage, which forms part of the exhibit on National Socialism in Frankfurt,[16] the visitor sees diagonally below it a broken Biedermeier chair. The chair likely originates from the Museum of Jewish Antiquities that opened in 1922 in the former house of the Rothschild banking family in Frankfurt, which was looted and destroyed in 1938.[17] To the left of the cage is a can of Zyklon B, the poison manufactured in Frankfurt and used for mass murder in concentration camps. Walking around this ‘island’ of glass display cases, the visitor sees behind the bird cage objects ranging from a silver swastika once used as a Christmas tree ornament in a Frankfurt household to silver teapots and cutlery that once belonged to Frankfurt Jews that were confiscated and forcibly sold by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 40s.

In this arrangement, where the tools of destruction clash with bourgeois Jewish urban and commemorative culture – a composition designed deliberately by the museum’s curators to create contradictions and startling object constellations – the dainty birdcage with its Frankfurt eagle naturally signifies the annihilated Jewish urban culture of Frankfurt. That Hackenbroch took this cage into exile and donated it to the museum posthumously as a gesture of reconciliation is only revealed through the inscription on the display case. In light of the juxtapositions, the repatriation of the birdcage and the concomitant reconciliation recedes into the background.

Nevertheless, the cage as gift also signals an intrinsic dialectic. After all, the cage as ‘prison’ refers to internment, execution and, with respect to exile, the forced escape from persecution, internment and death. The cage is thus not only a gesture of reconciliation and a symbolic return, but also an object of admonition.

Fig 5: Birdcage as shown on the Historische Museum Frankfurt’s website, Screenshot (https://historisches-museum-frankfurt.de/de/node/34467?language=de, 07.02.2023).

While the birdcage in the museum is presented in the context of the threat to and annihilation of Jewish culture in Frankfurt, assuming various, sometimes contradictory levels of meaning, the website depicts it as an isolated object. It is displayed there with an inventory number, object data and the text of the panel on the display case, which informs visitors about the donor, her history of exile and her gift as a sign of reconciliation. The question, then, is which presentation better does justice to the object, its only partially reconstructable history and to the exile of its previous owner?

Having first become acquainted with the birdcage virtually due to the pandemic, and only later being able to view it physically exhibited, I was initially surprised by the museum’s perceptual arrangement (Wahrnehmungsordnung).[18] The juxtaposition of the birdcage with the objects described above disturbed me, as I had not expected to see it next to a can of Zyklon B. In the words of Gottfried Korff, the placement of the birdcage in the museum put me, the visitor, ‘in a state of heightened, imagination-enhancing self-awareness’.[19] The objects are arranged to place the birdcage visually and conceptually in the context of National Socialism and its extermination machine, subordinated or eliminating other associations. According to Korff, ‘the subject [through museum arrangements, in the best case] should be freed of pragmatic references and become porous in the “performative” process of perception’.[20] Korff is highlighting the fact that visitors can become more receptive, permeable, ‘porous’ to historical, social and emotional entanglements through such provocative arrangements. In the case of the birdcage, however, it also means that we are not only reminded of the object’s connections to the period of National Socialism in Frankfurt, but are also reminded of the ruptures, detours, stations of exile — the dis:connections — contained in the fragmentary history of the birdcage.

Thus, the birdcage does not function exclusively as a symbol or memento. As a multi-dimensional object, it resists clear-cut interpretation and integration into discourses of exile or National Socialism. This is complicated further by the fact that, as Doerte Bischoff and Joachim Schlör argue, objects of exile retain a ‘minimal power […] to preserve human dignity’.[21] The birdcage as a symbol of incarceration (and therefore inhumanity) on the one hand and as the symbol of Hackenbroch’s endurance and dignity on the other combines in itself contradictions that cannot be easily resolved, transforming the birdcage into a truly dis:connected object.

Dis:connectivities in the museum: exile, return, reconciliation?

As Burcu Dogramaci and her colleagues aptly describe in their preface to an edition of the Jahrbuch Exilforschung devoted to archives and museums of exile, the ‘placement of such materials in archives and museums [confronts us] with a tension between a delimiting situatedness, on the one hand, and a portability and boundarylessness to which they themselves bear witness’.[22] With respect to Yvonne Hackenbroch’s birdcage, this tension arises not only from the object’s placement in the museum, but from the cage itself, which, as a movable thing, paradoxically exists to restrict the bird’s freedom of movement. The birdcage embodies the indissoluble dialectic of exile as ‘liberation’ from persecution, on the one hand, and captivity in a foreign land on the other. It symbolises an intermediate state best described by Rafael Cardoso: ‘Exile, in the broad sense of the term, is a condition. One that involves simultaneous absence and presence […]. There is a liminality to this condition, an essential in-betweenness, that precludes ever arriving at anything so clear cut and unambiguous as freedom of the past.’[23]The return of the birdcage to the Historical Museum in Frankfurt is not an unequivocal gesture of reconciliation. Instead, the birdcage carries Hackenbroch’s exile experience within it and affects us, as Arjun Appadurai argues, through ‘the force of [its] histories, journeys, accidents and adventures’.[24] Hackenbroch’s birdcage, then, is an ambivalent signifier of forced emigration and ‘dislocation’ that challenges us to see the experience of exile as a ‘cage perspective’ rooted in violent displacement from which there can be no liberation, not even for those standing outside the cage.

[1] ‘ Zeichen der Versöhnung’ as worded in the object description of the museum: https://historisches-museum-frankfurt.de/de/node/34467, last accessed on 3 February. 2023, and: Jan Gerchow and Nina Gorgius, eds., 100 * Frankfurt: Geschichten aus (mehr als) 1000 Jahren (Frankfurt: Societäts Verlag, 2017), 274–75.

[2] Neither the Hackenbroch family nor the museum curators were able to provide any information in this regard.

[3] Adam Hills, Email to author, 21 February 2022.

[4] Tilman Habermas, Geliebte Objekte. Symbole und Instrumente der Identitätsbildung (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1996), 281.

[5] Habermas, 278.

[6] Julia Breittruck, Ein Flügelschlag in der Pariser Aufklärung: Zur Geschichte der Beziehungen zwischen Menschen und ihren Vögeln (Munich: University Library LMU, 2021).

[7] Breittruck, 3–39.

[8] This is based on research in the image library of the European Cultural Heritage Database, which I cannot discuss here due to space limitations: https://www.europeana.eu/de, Access date missing

[9] Breittruck, Ein Flügelschlag in der Pariser Aufklärung: Zur Geschichte der Beziehungen zwischen Menschen und ihren Vögeln, 40.

[10] Breittruck, 53–54.

[11] Breittruck, 40 et seq.

[12] Breittruck, 41.

[13] Breittruck, 83.

[14] Breittruck, 87.

[15] Krzysztof Pomian, Der Ursprung des Museums: Vom Sammeln (Berlin: Wagenbach, 1988).

[16] My visit to the Historical Museum in Frankfurt took place in May 2022. I thank the curators Nina Gorgus and Anne Gemeinhardt for their help and cooperation in my research.

[17] Gerchow and Gorgius, 100 * Frankfurt: Geschichten aus (mehr als) 1000 Jahren, 277–79, on the Can of Zyklon B, 291– 93.

[18] Gottfried Korff, ed., ‘Speichern und/oder Generator: Zum Verhältnis von Deponieren und Exponieren im Museum’, in Museumsdinge, deponieren/exponieren, 2nd ed. (Cologne: Böhlau Verlag, 2007), 172.

[19] Korff, 173.

[20] Korff, 172.

[21] Doerte Bischoff and Joachim Schlör, ‘Dinge des Exils. Zur Einleitung’, in Dinge des Exils, Jahrbuch Exilforschung 31, 9-22. (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2013), 18.

[22] Sylvia Asmus, Doerte Bischoff, and Burcu Dogramaci, eds., Archive und Museen des Exils, Jahrbuch Exilforschung 37 (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2018), 2.

[23] Rafael Cardoso, ‘The living archive: On Hugo Simon’s posthumous return to Germany’, in Archive und Museen des Exils, Jahrbuch Exilforschung 37 (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2019), 106.

[24] Arjun Appadurai, ‘Museum Objects as Accidental Refugees’, Historische Anthropologie 25, no. 3 (November 2017): 406.

Bibliography

Appadurai, Arjun. ‘Museum Objects as Accidental Refugees’. Historische Anthropologie 25, no. 3 (November 2017): 401–8.

Asmus, Sylvia, Doerte Bischoff, and Burcu Dogramaci, eds. Archive und Museen des Exils. Jahrbuch Exilforschung 37. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2018.

Bischoff, Doerte, and Joachim Schlör. ‘Dinge des Exils. Zur Einleitung’. In Dinge des Exils, Jahrbuch Exilforschung 31, 9-22. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2013.

Breittruck, Julia. Ein Flügelschlag in der Pariser Aufklärung: Zur Geschichte der Beziehungen zwischen Menschen und ihren Vögeln. Munich: University Library LMU, 2021.

Cardoso, Rafael. ‘The living archive: On Hugo Simon’s posthumous return to Germany’. In Archive und Museen des Exils, Jahrbuch Exilforschung 37, 96–107. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2019.

Gerchow, Jan, and Nina Gorgius, eds. 100 * Frankfurt: Geschichten aus (mehr als) 1000 Jahren. Frankfurt: Societäts Verlag, 2017.

Habermas, Tilman. Geliebte Objekte. Symbole und Instrumente der Identitätsbildung. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1996.

Korff, Gottfried, ed. ‘Speichern und/oder Generator: Zum Verhältnis von Deponieren und Exponieren im Museum’. In Museumsdinge, deponieren/exponieren, 2nd ed. Cologne: Böhlau Verlag, 2007.

Pomian, Krzysztof. Der Ursprung des Museums: Vom Sammeln. Berlin: Wagenbach, 1988.