In

Blog 2022

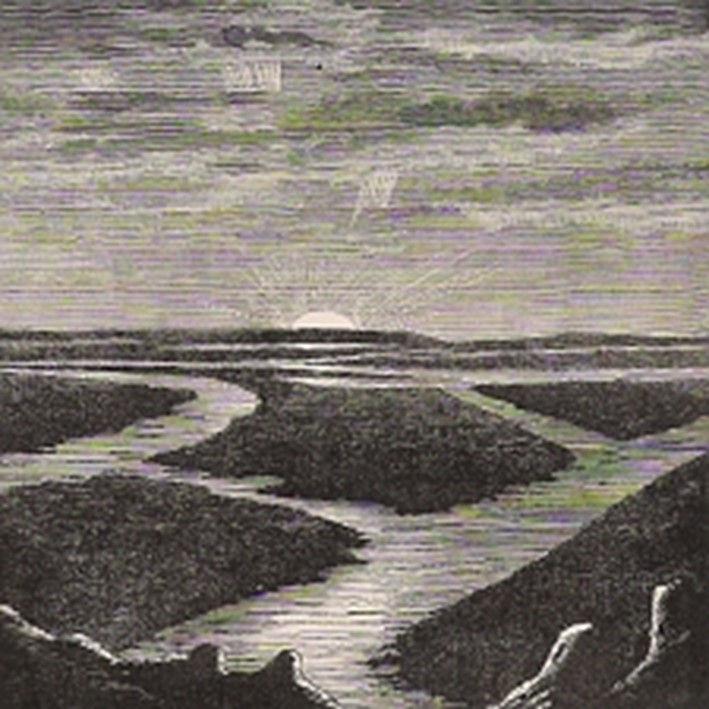

It might seem a strange question. Isn’t the answer obvious? We see a cloudy sky. The viewer’s gaze is drawn to the horizon where the sun is either rising or setting. The mood is calm and peaceful. In the foreground, we see a marshland streaked with channels, though seemingly untouched and natural. Something is peeking into the immediate foreground. It could be rocks or a wooden fence, imparting the impression of looking down on the lonely landscape from a hill.

But the motif is very different from what it appears to be. It is no peaceful marshland. Rather, it’s Marsland: a depiction of the surface of Mars. And it is by no means as untouched and unspectacular as it may appear.

It might seem a strange question. Isn’t the answer obvious? We see a cloudy sky. The viewer’s gaze is drawn to the horizon where the sun is either rising or setting. The mood is calm and peaceful. In the foreground, we see a marshland streaked with channels, though seemingly untouched and natural. Something is peeking into the immediate foreground. It could be rocks or a wooden fence, imparting the impression of looking down on the lonely landscape from a hill.

But the motif is very different from what it appears to be. It is no peaceful marshland. Rather, it’s Marsland: a depiction of the surface of Mars. And it is by no means as untouched and unspectacular as it may appear.

A depiction of the imagined system of canals on Mars. Title of Cosmopolitan Magazine XLIV, 4 (March 1908). https://www.loc.gov/item/cosmos000114.

This theory about life on Mars featured prominently in the discussion around 1900 about whether the new wireless communication technology could be used to communicate with extra-terrestrial beings — a discussion electrified by pioneers of that technology, like Nikola Tesla and Guglielmo Marconi, as well as the keen interest of the press. Already in 1892, Flammarion was convinced that the prospect of communicating with extra-terrestrials was ‘not at all absurd’.[8] In fact, Tesla published an article in 1901 claiming that he had actually received extra-terrestrial signals with a wireless device. They must have been signs of intelligent life, as they gave a ‘clear suggestion of number and order’. Tesla also prophesied that ‘with the novel means […] signals can be transmitted to a planet such as Mars’,[9] rendering interplanetary conversations thinkable. According to the press, Marconi, too, revealed in 1920 that he believed some of the signals he had received during his experiments ‘originated in the space beyond our planet’ and had been ‘sent by the inhabitants of other planets to the inhabitants of earth’. He even explicitly referred to the inhabitants of Mars when he stated that he ‘would not be surprised if they should find a means of communication with this planet.’ As ‘our own planet is a storehouse of wonders’, nothing seemed impossible.[10]

Continue Reading

A depiction of the imagined system of canals on Mars. Title of Cosmopolitan Magazine XLIV, 4 (March 1908). https://www.loc.gov/item/cosmos000114.

This theory about life on Mars featured prominently in the discussion around 1900 about whether the new wireless communication technology could be used to communicate with extra-terrestrial beings — a discussion electrified by pioneers of that technology, like Nikola Tesla and Guglielmo Marconi, as well as the keen interest of the press. Already in 1892, Flammarion was convinced that the prospect of communicating with extra-terrestrials was ‘not at all absurd’.[8] In fact, Tesla published an article in 1901 claiming that he had actually received extra-terrestrial signals with a wireless device. They must have been signs of intelligent life, as they gave a ‘clear suggestion of number and order’. Tesla also prophesied that ‘with the novel means […] signals can be transmitted to a planet such as Mars’,[9] rendering interplanetary conversations thinkable. According to the press, Marconi, too, revealed in 1920 that he believed some of the signals he had received during his experiments ‘originated in the space beyond our planet’ and had been ‘sent by the inhabitants of other planets to the inhabitants of earth’. He even explicitly referred to the inhabitants of Mars when he stated that he ‘would not be surprised if they should find a means of communication with this planet.’ As ‘our own planet is a storehouse of wonders’, nothing seemed impossible.[10]

Continue Reading

Mars and the urge to connect around 1900

anna sophia nübling

What do you think this drawing depicts?

Marsland from Les Terres du Ciel (1884)

Theories about connected life on Mars around 1900

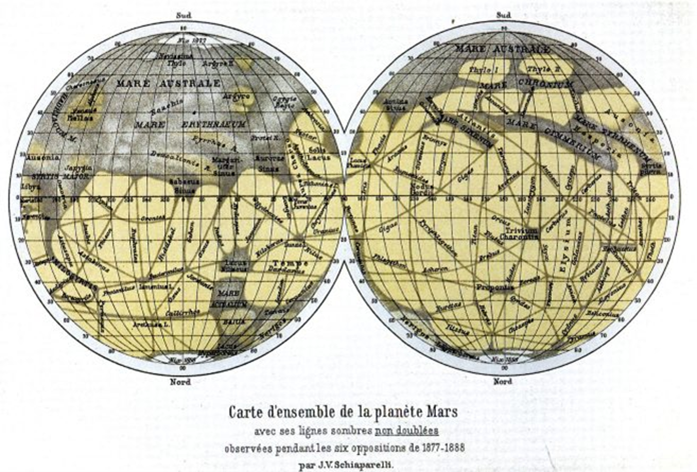

The drawing is taken from a book titled Les Terres du Ciel, published in 1884 by the French astronomer Camille Flammarion.[1] In this publication, Flammarion argued (as in many other books he authored[2]) that Earth was not the only inhabited planet. Life on other planets, he was convinced, was highly probable. Whether or not life exists elsewhere is an old debate,[3] but as for Mars, there seemed to be proof, since in 1877 the astronomer Giovanni Sciaparelli claimed to have seen channels on the surface. Other astronomers, like Flammarion in France or Percival Lowell in the USA, reaffirmed this observation and argued that these channels must be artificial, interpreting them as huge canals created by Martian creatures.[4] Mars seemed especially suitable for life, as it appeared geographically and chemically very similar to Earth.[5] Lowell in particular propounded the thesis that Martians were building vast canals, as ever more seemed to be appearing over time. Referring to Lowell, the New York Times from 27 August 1911 headlined: Martians Build Two Immense Canals in Two Years. Vast Engineering Works Accomplished in an Incredibly Short Time by Our Planetary Neighbors.[6] Lowell, according to this newspaper article, had detected canals of which there had been no trace two years before. No natural reason for their existence, such as ‘seasonal changes’ on Mars, could explain these new canals. They must have been built! Their geometric arrangement encouraged this interpretation — ‘of most orderly self-restraint’ and ‘wonderfully clear cut’, as the author of the Times article quoted Lowell.[7] Therefore, they must have been the result of engineering. Around the turn of the twentieth century, this theory found considerable resonance in popular culture, as is well known. It inspired works of literature and film such as H.G. Wells’s War of the Worlds and fuelled an imaginary of Mars that remains vivid today. A depiction of the imagined system of canals on Mars. Title of Cosmopolitan Magazine XLIV, 4 (March 1908). https://www.loc.gov/item/cosmos000114.

This theory about life on Mars featured prominently in the discussion around 1900 about whether the new wireless communication technology could be used to communicate with extra-terrestrial beings — a discussion electrified by pioneers of that technology, like Nikola Tesla and Guglielmo Marconi, as well as the keen interest of the press. Already in 1892, Flammarion was convinced that the prospect of communicating with extra-terrestrials was ‘not at all absurd’.[8] In fact, Tesla published an article in 1901 claiming that he had actually received extra-terrestrial signals with a wireless device. They must have been signs of intelligent life, as they gave a ‘clear suggestion of number and order’. Tesla also prophesied that ‘with the novel means […] signals can be transmitted to a planet such as Mars’,[9] rendering interplanetary conversations thinkable. According to the press, Marconi, too, revealed in 1920 that he believed some of the signals he had received during his experiments ‘originated in the space beyond our planet’ and had been ‘sent by the inhabitants of other planets to the inhabitants of earth’. He even explicitly referred to the inhabitants of Mars when he stated that he ‘would not be surprised if they should find a means of communication with this planet.’ As ‘our own planet is a storehouse of wonders’, nothing seemed impossible.[10]

A depiction of the imagined system of canals on Mars. Title of Cosmopolitan Magazine XLIV, 4 (March 1908). https://www.loc.gov/item/cosmos000114.

This theory about life on Mars featured prominently in the discussion around 1900 about whether the new wireless communication technology could be used to communicate with extra-terrestrial beings — a discussion electrified by pioneers of that technology, like Nikola Tesla and Guglielmo Marconi, as well as the keen interest of the press. Already in 1892, Flammarion was convinced that the prospect of communicating with extra-terrestrials was ‘not at all absurd’.[8] In fact, Tesla published an article in 1901 claiming that he had actually received extra-terrestrial signals with a wireless device. They must have been signs of intelligent life, as they gave a ‘clear suggestion of number and order’. Tesla also prophesied that ‘with the novel means […] signals can be transmitted to a planet such as Mars’,[9] rendering interplanetary conversations thinkable. According to the press, Marconi, too, revealed in 1920 that he believed some of the signals he had received during his experiments ‘originated in the space beyond our planet’ and had been ‘sent by the inhabitants of other planets to the inhabitants of earth’. He even explicitly referred to the inhabitants of Mars when he stated that he ‘would not be surprised if they should find a means of communication with this planet.’ As ‘our own planet is a storehouse of wonders’, nothing seemed impossible.[10]

Connectivity as a feature of progress

The story of the nineteenth-century fascination with Mars has been told many times.[11] Of course, as far as we know there were and are no real connections at all, neither canals on Mars nor signals from Martians. But around the turn of the twentieth century, people started to imagine them, and this is no less interesting. The whole story about Martians building infrastructure and communicating is about them being connected to each other and even to the inhabitants of other worlds. Obviously, this tells us less about Mars than about the significance and valuation of connections and connectivity as they were perceived on Earth at that time. Imagining extra-terrestrial beings is, therefore, not about imagining the other, as is often argued in scholarship,[12] but about imagining oneself.[13] Here begins historians’ interest in Martian canals, at least those historians seeking to offer a more nuanced and less normative history of the role connections have played in making of the modern world. They offer an unusual point of departure for a critical history of the euphoria induced by connectivity and its implications. First, the obvious: discussions about canals on Mars and communicating Martians reflect recent experiences on Earth. Martian canals would have been unthinkable without the impressive technological developments of the nineteenth century. Flammarion, for instance, explicitly mentioned alpine tunnels, the Suez Canal (opened in 1869), the Panama Canal (opened in 1914), and, more generally, railways, telegraphy, electricity, photography and the telephone.[14] Around 1900, speculation about communicating with Mars became a fanciful extrapolation on the future use of the new wireless technology. More abstractly, however, visions of infrastructure-building and communicating Martians reveal a lot about late-nineteenth and early twentieth-century assumptions about the significance of connectedness for the idea of progress. Tesla took for granted that Mars was best suited for communication with Earth because ‘its intelligent races […] are far superior than us.’[15] The planet’s beneficial climate, but especially its age, supported that widespread conviction.[16] Flammarion, for example, found it ‘naturel’ and ‘logique’ that the greater age of ‘humanité’ on Mars made it ‘plus perfectionnée’ than that on Earth.[17] Evolution, according to Flammarion, occurred on all inhabited worlds the very same way. A ‘long-period comet passing in sight of the Earth from time to time’, he envisioned, ‘would have seen modifications of existence in each of its transits, in accordance with a slow evolution […] progressing incessantly, for if Life is the goal of nature, Progress is the supreme law.’ And this law of evolutionary progress, he was convinced, was ‘the same for all worlds’.[18] For observers on Earth, Martians’ ability to build huge canals and to communicate with wireless was the ultimate proof that evolution had led Martians to a higher stage of development. The famous inventor Thomas Edison, for example, in 1920 equated technologically assisted communication with advancement, stating that: ‘If we are to accept […] that these signals are being sent out by inhabitants of other planets, we must at once accept with it the theory of their advanced development’.[19] And as for the canals, the writer H.G. Wells made use of the typical argument in an 1908 article in Cosmopolitan Magazine about Things that live on Mars. Referring again to the correlation between age and advancement, he speculated that ‘Martians are probably far more intellectual than men and more scientific’. He attributed this alleged Martian advancement to the fact that they were, according to him, ‘creatures of sufficient energy and engineering science’, who were able ‘to make canals beside which our greatest human achievements pale into insignificance’.[20]Outer space and global history

Discussions about life on Mars around 1900 are, therefore, more than mere fanciful speculation. Reading them as reflections about the familiar rather than the other, they reveal deep-reaching assumptions about the nature of connectedness and its normative implications. They indicate that connectivity had become an important marker of progress. Both a state of being connected and the ability to build connective technology became signs of the evolutionary advancement of a particular place, territory, or even an entire planet. Global historians should take this as a reminder that connectivity often had and has normative implications as an indicator of advancement in a progressive teleology. Those without connections or broken connections were perceived as laggards in the scheme of evolution — be they in Africa or Mercury. The drawing that opened this essay, we may conclude, is not a romantic scene, but an important sign of a cosmological theory of progress by means of connectivity where technological infrastructure is the most important factor (and evidence). It is a vision that, in cosmological terms, extends beyond Mars and in which outer space is potentially full of communicating empires. Such assumptions suffuse not only science fiction, but were also formative when the Search for Extra-terrestrial Intelligence became a state-funded scientific enterprise in the 1960s in the USA and elsewhere — but that’s another story. [1] Camille Flammarion, Les terres du ciel (Paris, 1884), 65. [2] Flammarion published his first book, La pluralité des mondes habités in 1862 at the age of twenty. Especially for Mars, see also Camille Flammarion, La planète Mars et ses conditions d’habitabilité (Paris, 1892). [3] For the history of the idea of extra-terrestrial life, see Michael Crowe, The Extraterrestrial Life Debate 1750-1900. The Idea of a Plurality of Worlds from Kant to Lowell (Cambridge, 1986). [4] Helga Abret and Lucian Boia, Das Jahrhundert der Marsianer. Der Planet Mars in der Science Fiction bis zur Landung der Viking-Sonden 1976. Ein Science-Fiction Sachbuch (München, 1984), 44. Lowell published his ideas about Mars in his books Mars (Boston et al., 1895), Mars and Its Canals (New York, 1906) and Mars as the Abode of Life (New York, 1908). [5] Flammarion, La planète Mars et ses conditions d’habitabilité, 589. [6] Mary Proctor, ‘Martians Build Two Immense Canals in Two Years’, The New York Times Sunday Magazine 1911 (27 August 1911). [7] Ibid. [8] Crowe, The Extraterrestrial Life Debate 1750-1900, 395. [9] Nikola Tesla, ‘Talking with the Planets’, Collier’s Weekly 1901 (9 February 1901): 5–6. [10] ‘Hello Earth! Hello! Marconi Believes He Is Receiving Signals from the Planets’, The Tomahawk 1920 (18 March 1920). One of his recent biographers, however, clearly understates Marconi’s belief in extra-terrestrials Marc Raboy, Marconi: The Man Who Networked the World (Oxford, 2016), 471. [11] Most comprehensively, Mars has been studied as a topic of literature and film. See, for example, Justus Fetscher and Robert Stockhammer, eds., Marsmenschen: Wie Die Außerirdischen gesucht und erfunden wurden (Leipzig, 1997). [12] As, for example, John D. Peters argues in his book John D. Peters, Speaking into the Air. A History of the Idea of Communication (Chicago/London, 2000), 230. [13] I agree with Roland Barthes, who put it thus: ‘Der Mars ist […] bloß eine erträumte Erde’. And more boldly: ‘die Unfähigkeit, sich das Andere vorzustellen, ist einer der durchgängigsten Züge jener kleinbürgerlichen Mythologie [des ‘Mythos des Selben’].’ Roland Barthes, Mythen des Alltags. Aus dem Französischen von Horst Brühmann, trans. Horst Brühmann (Berlin, 2010), 54, 55. [14] Flammarion, La planète Mars et ses conditions d’habitabilité, 586. [15] Crowe, The Extraterrestrial Life Debate 1750-1900, 395. [16] Beyond those mentioned, see, for the typical argument, Elias Colbert, Star-Studies. What We Know of the Universe Outside the Earth (Chicago, 1871), 78. [17] Flammarion, La planète Mars et ses conditions d’habitabilité, 586–87. [18] Camille Flammarion, Astronomy for Amateurs, New York 1904 (First Published in French in 1894) (New York, 1904), 331. [19] ‘Hello Earth! Hello! Marconi Believes He Is Receiving Signals from the Planets’. [20] H.G. Wells, ‘The Things That Live on Mars’, Cosmopolitan Magazine XLIV, no. 4 (March 1908): 342.bibliography

Abret, Helga, and Lucian Boia. Das Jahrhundert der Marsianer. Der Planet Mars in der Science Fiction bis zur Landung der Viking-Sonden 1976. Ein Science-Fiction Sachbuch. München, 1984. Barthes, Roland. Mythen des Alltags. Aus dem Französischen von Horst Brühmann. Translated by Horst Brühmann. Berlin, 2010. Colbert, Elias. Star-Studies. What We Know of the Universe Outside the Earth. Chicago, 1871. Crowe, Michael. The Extraterrestrial Life Debate 1750-1900. The Idea of a Plurality of Worlds from Kant to Lowell. Cambridge, 1986. Fetscher, Justus, and Robert Stockhammer, eds. Marsmenschen: Wie Die Außerirdischen Gesucht Und Erfunden Wurden. Leipzig, 1997. Flammarion, Camille. Astronomy for Amateurs, New York 1904 (First Published in French in 1894). New York, 1904. ———. La planète Mars et ses conditions d’habitabilité. Paris, 1892. ———. Les terres du ciel. Paris, 1884. ‘Hello Earth! Hello! Marconi Believes He Is Receiving Signals from the Planets’. The Tomahawk 1920 (18 March 1920). Peters, John D. Speaking into the Air. A History of the Idea of Communication. Chicago/London, 2000. Proctor, Mary. ‘Martians Build Two Immense Canals in Two Years’. The New York Times Sunday Magazine 1911 (27 August 1911). Raboy, Marc. Marconi: The Man Who Networked the World. Oxford, 2016. Tesla, Nikola. ‘Talking with the Planets’. Collier’s Weekly 1901 (9 February 1901): 5–6. Wells, H.G. ‘The Things That Live on Mars’. Cosmopolitan Magazine XLIV, no. 4 (March 1908): 342.citation information

Nübling, Anna Sophia. ‘Mars and the Urge to Connect around 1900’. Blog, Global Dis:Connect (blog), 6 September 2022. https://www.globaldisconnect.org/09/06/mars-and-the-urge-to-connect-around-1900/?lang=en.

6 September 2022