Pilgrimage to the Holy Land in the 16th-17th centuries: disconnectivites and the shaping of cultural imaginaries

chiara di carlo

I want to show how pilgrimage to the Holy Land helped mitigate Europeans’ fear of the Turks and the Ottoman world. Especially the accounts of the Holy Land produced between the 16th and 17th centuries are valuable testimonies that show us not only a real journey, but an inner journey as well. These accounts reveal how fragile the popular imaginary was, made up of the pilgrims’ own fears, highlighting the dynamics of cultural disconnections and reconnections, especially between Italian-Christian and Ottoman-Islamic popular culture. Starting with the European popular context, I will show the common imaginary of ‘the Turk’ and how pilgrimage, along with other factors, eased collective fears.The European imaginary

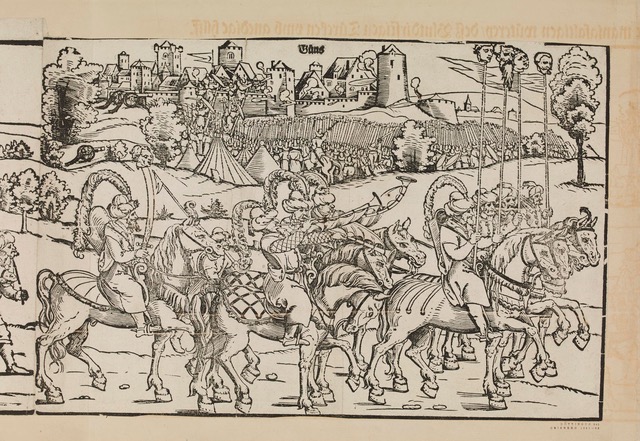

Between the fall of Constantinople in 1453 to the Christian defense of Vienna in 1683, the Turkish question was one of the most debated topics in European society. Thanks to the advent of movable-type printing, publicity, diaries and the Itinera Terrae Sanctae (i.e. pilgrims’ travelogues) contained news about the Turkish world, culturally distant but geographically now at the gates of Christian Europe.[1] From the 15th century, knowledge about Islam was increasing, especially under Pope Pius II (1458-1464), who encouraged the study of Muslims. According to the pope – and this view became common over the years – the success of Muhammad’s religion was mainly due to the supposed licentiousness of the Turks’ sexual mores, as they were perceived as lustful and sodomites. This narrative aroused concern among European publics.[2] An example is found in I cinque libri della legge, religione, et vita de’ Turchi et della Corte, et d’alchune guerre del Gran Turcho by Menavino. The author writes: ‘The vice of lust is still present among Muslims, considering it a completely abominable behavior. According to their law, everyone is obliged to legitimately take a wife to eradicate this sin and all other forms of fornication. Women are so strongly tainted by the vice of sodomy that it is impossible for many of them to abstain from it. Since all are tainted by this stain, they do not punish each other and it is stated in their Quran that those who practice this vice are lost’.[3] Europeans’ images of the Turks were largely influenced by prints and news stories. A clear example is found in a graphic work by the Bolognese artist Giuseppe Maria Mitelli (fig.1). The print depicts passers-by, scandalised and frightened, fleeing, refusing to take in the news, as the seller holds a portrait of a man wearing a turban – an image that was widespread as early as the mid-16th century.[4]

Fig 1. Giuseppe Maria Mitelli, Compra Chi Vuole / Avisi Di Guerra / Carte Di Guerra / À Buon Mercato, À Due Bolognini / L'una, 1684, Etching, 193 x 270 mm, Gonnelli Firenze, sale 31 / grafica & libri, 29 October 2021, lot 17.

Fig. 2 Erhard Schön, Fragment of a broadside on the Turkish invasion of Hungary, 1532, print, 42.32 x 29.17 cm, © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Pilgrimage and travel reports

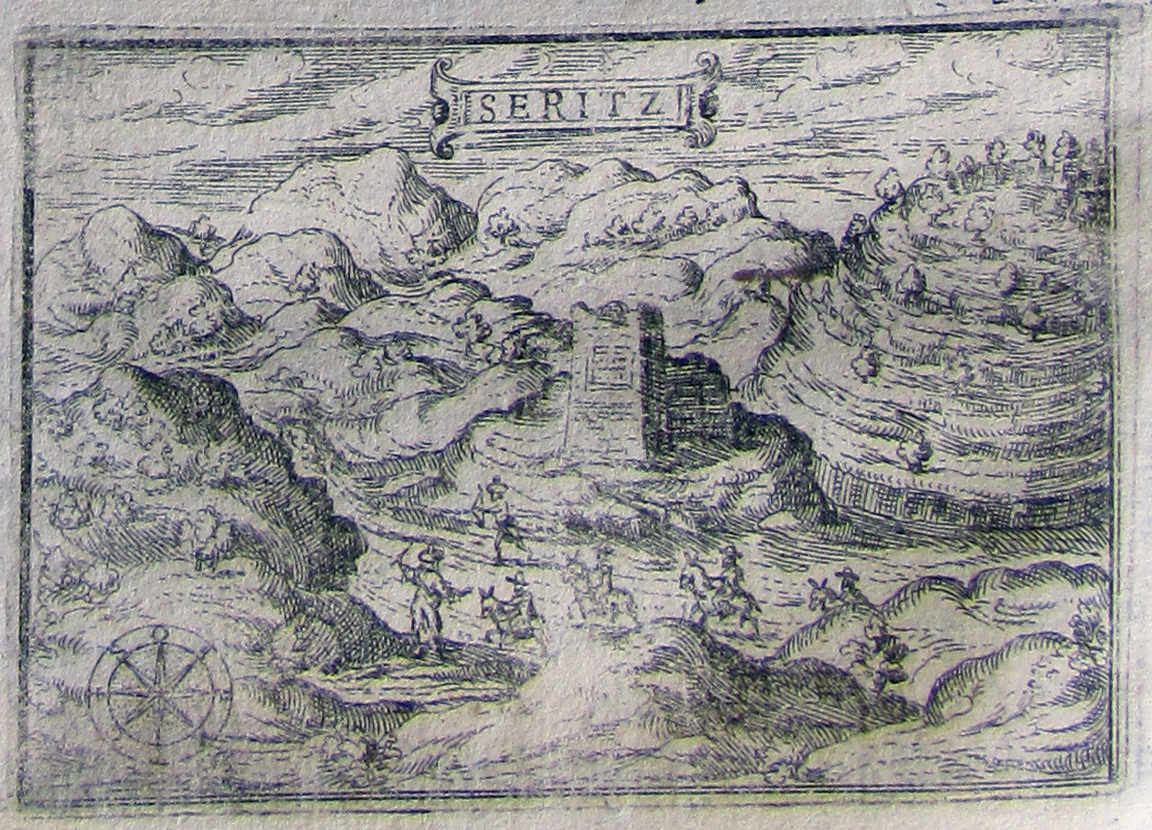

The cultural and figurative context described up to this point represents the frame of reference for the pilgrims and those who read their travelogues. Despite the temporal and cultural distance, the Itinera ad Loca Sancta[7] allows us to ‘re-enter’ those lands thanks to another important aid: images. The writers were the same pilgrims who, between the 16th and 17th centuries, set out for spiritual reasons, but also for ‘entrepreneurial’[8] and ‘political’ ones. Their reports often reflected what the powerful in Christendom expected to hear. Especially Bartholomeo Georgijević[9] spoke of the Holy Land as ‘alienated and doomed, pervaded by dissensions and neglected by the principles of the Christian Republic, it is a barbarian land now under the rule of the Turks.’[10] He told of holy places in and around Jerusalem, sadly damaged by the ‘infidels’ who ruled and guarded it. He also tells of the terror they instilled in the traveller-pilgrims, who were forced to endure numerous restrictions. For example, they were confined to the monastery where they resided lest they be robbed or killed, and they were not allowed to possess any kind of weapon.[11] However, even this fear proved fallacious; some writers, such as Aquilante Rocchetta,[12] recounted that they had never seen or heard of pilgrims killed by the Turks,[13] thus proposing an alternative image. Again, Georgijević regretted not only the cost of living, but also a kind of slavery due to the toll required to enter the Holy Places. Zuallart’s[14] text contains an exemplary print, showing pilgrims stopped on their way to pay the fee (fig. 3).[15] However, the Croatian author’s regret was the same felt by a Muslim pilgrim visiting Jerusalem in late 900 AD, when the Arab geographer Al-Muqaddasi recounted the disadvantages of visiting the city in Catholic hands. Among his complaints were the cost of living, the prices of public baths and hostels, and the oppressive vigilance of the guards at the city gates that curtailed trade.[16] ‘Then again, how could it be otherwise,’ Muquaddasi wonders, ‘given the prevaricating manner in which Christians behaved in public places’.[17]

Fig. 3 Seritz in Jean Zuallart, Il devotissimo viaggio di Gerusalemme, print, 1586, 60 x 85 cm. © Bibliotheca Terrae Sanctae. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

[1] Massimo Moretti, 'Dalle “pancacce” ai piatti. Percezioni e rappresentazioni del Turco nella cultura popolare del Cinquecento', in Storie intrecciata. Rappresentazioni e conoscenza dell'Islam nell'Italia moderna, ed. Serena Di Nepi (Rome: Edizioni di storia e letteratura, 2015), 131-32. [2] Moretti, 'Dalle “pancacce” ai piatti', 136. [3] ‘l vitio della Lussuria hanno anchora i mahomettani per cosa in tutto abominevole. Perché secondo la lor legge, tutti sono costretti di pigliar legittima sposa, per tor via questo peccato, et ogni altra fornicazione [...]. Conciosia che oltra le donne, sono molto imbrattati del vitio della sodomia; in modo tale, che non è possibile per alcuna via, se ne possano astenere. Et perché tutti sono macchiati di questa pece, fra loro non ne danno punitione, et hanno nel loro coran, che quelli che usano questo vitio, sono perduti’. Giovanni Antonio Menavino, I cinque libri della legge, religione, et vita de’ Turchi: et della corte, & d'alcune guerre del Gran Turco (Venice: Vincenzo Valgrisi, 1548). Unless otherwise indicated, all translations are by the author. [4] Moretti, 'Dalle “pancacce” ai piatti', 139. [5] There are numerous texts expressing negative views of the Turks, especially the writings of Bartholomew Georgijević. See: Profetia de i Turchi, della loro rovina, o la conversione alla fede di Christo per forza della spada Christiana; Specchio de' lochi sacri di Terra Santa, che comprende quattro libretti, si come leggendo questo seguente foglio, potrai intendere. [6] Niccolò Machiavelli, Opere di Niccolò Machiavelli cittadino e segretario fiorentino, vol. VIII (Florence: Piatti, 1813), 60. [7] Most of the books analysed here date from the 16th and 17th centuries. Some of the texts were covered in my 2019 dissertation as part of a project coordinated by Prof. Massimo Moretti (University of Rome La Sapienza) on reconstructing the image of the last Duke of Urbino, Francesco Maria II della Rovere through the study of his ‘Libraria.’ [8] Bernard von Breydenbach's Peregrinationes plays a fundamental role in the modern age, anticipating the volumes examined in the text. It is the first illustrated travel book, a mix of diary and guidebook, representing a path of culture and knowledge. Breydenbach's pilgrimage was selective, with a mystical experience complementing the primarily commercial purpose: an opportunity to bring his pamphlet to life. He set out intending to write a book on his return, to include illustrations that would reinforce the words, and hoping to have it published. That is, he grasped the possible outcomes (including commercial ones) of printing, bringing the painter Erhard Reuwich along to create the illustrations. Gabriella Bartolini and Giulio Caporali, Peregrinationes. Un viaggiatore del Quattrocento (Rome: Vecchiarelli, 1999), 12-18. [9] Georgijević was born in Croatia around 1505 and was captured by the Turks after the Battle of Mohács in 1526. He spent time in captivity, working as a farmer and shepherd, and escaped in 1535. In Rome from 1540 to 1560, he published works and received a modest pension as a 'humiliated'. The veracity of his experience as a prisoner and pilgrim is in doubt, as he may have imagined part of it. [10] ‘Alienata e biasimata, abitata da discordia e negligenza dei principi della Repubblica Cristiana e terra di barbarie occupata dai Turchi. ' [11] Bartolomeo Georgijević, Specchio de' lochi sacri di Terra Santa, che comprende quattro libretti, si come leggendo questo seguente foglio, potrai intendere (Rome: Bolano, 1566). [12] Rocchetta, a Calabrian traveler, wrote a report about his pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1598. This diary offers a detailed account of his experiences at holy sites, providing valuable information for future pilgrims. [13] ‘On this Voyage, we have rarely heard of Pilgrims being killed by Arab thieves or captured by Turks. On the contrary, at sea, the boats we pass belong to Turkish merchants who do not carry out acts of capture or theft. On the contrary, many times they provide us with assistance when we need it, supplying us with wood and water when there is a shortage’. Aquilante Rocchetta, Peregrinatione di Terra Santa e d’altre provincie di Don Aquilante Rocchetta Cavaliere del Santissimo Sepolcro. Nella quale si descrive distintamente quella di Christo secondo gli Evangelisti (Palermo: Alfonzo Dell’Isola, 1630). [14] Zuallart was born in 1541 in Ath, Belgium. After a trip to Germany and Italy with Philippe de Mérode, the latter suggested to Zuallart that he make a pilgrimage to Palestine to compile a guidebook on his return. With great will, Zuallart learned the art of drawing in a few months and was thus able to illustrate the story with realistic images, besting other works’ figurative art and becoming very successful. [15] Jean Zuallart, Il devotissimo viaggio di Gerusalemme fatto, & descritto in sei libri (Rome: Francesco Zannetti and Giacomo Ruffinelli, 1587), 118. [16] Attilio Brilli, Il grande racconto del viaggio in Italia. Itinerari di ieri per viaggiatori di oggi (Bologna: Il mulino, 2019), 72,23. [17] Brilli, Il grande racconto. [18] Lucia Rostagno, 'Pellegrini italiani a Gerusalemme in età ottomana: percorsi, esperienze, momenti d’incontro', Oriente Moderno 17, no. 1 (1998): 82. [19] Alcarotti, born in Novara in 1535, was a composer and organist. He spent much of his youth in Rome studying. Belonging to a wealthy family, he had the opportunity to visit Italy's major cities and made the pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1588. On his return he wrote a guidebook. See: Giovanni Francesco Alcarotti, Del viaggio di Terra Santa. Da Venetia à Tripoli, di Soria (Novara: Francesco Sesalli, 1596). [20] ‘Tutto che siano i Turchi, nemici di nostra fede, più tosto si lascerebbero tagliar a pezzi, che lasciar maltrattare quelli, che esse prendono in guardia e sotto la loro protezione’. Rocchetta, Peregrinatione di Terra Santa. [21] Rostagno, 'Pellegrini italiani', 99.

Holt’s paper, for example, evoked the relevance of mineral resources in the context of digitalisation, especially with regard to the humanities. Mineral resources make our daily life possible, though we take them for granted. Digitalisation, which is as indomitable as it is universal, also shapes our research practices and relies heavily on mineral resources. This text, for instance, was written on a laptop produced in Taiwan with mineral resources from China and Latin America, and I also use it to read digital papers by scholars from the Netherlands, the USA and India.

The more we digitalise, the more we lose a genuine connection to our analogue environment. But ironically, that same digitalisation and environmental alienation coincides with greater environmental exploitation. Materials are a medium by which we surpass our natural boundaries and enter a digital space. We do well to remember, however, that this journey is predicated on natural resources. The virtuality of digitalization is an illusion. In the end, everything is analogue.

Many of the presentations, especially those from Boddy, Grüner, Mishra and Moore highlighted the importance of reflecting on emotions in research. Art is emotion; it is, to paraphrase Benjamin Myers, the desire to cast the moment in amber.

Holt’s paper, for example, evoked the relevance of mineral resources in the context of digitalisation, especially with regard to the humanities. Mineral resources make our daily life possible, though we take them for granted. Digitalisation, which is as indomitable as it is universal, also shapes our research practices and relies heavily on mineral resources. This text, for instance, was written on a laptop produced in Taiwan with mineral resources from China and Latin America, and I also use it to read digital papers by scholars from the Netherlands, the USA and India.

The more we digitalise, the more we lose a genuine connection to our analogue environment. But ironically, that same digitalisation and environmental alienation coincides with greater environmental exploitation. Materials are a medium by which we surpass our natural boundaries and enter a digital space. We do well to remember, however, that this journey is predicated on natural resources. The virtuality of digitalization is an illusion. In the end, everything is analogue.

Many of the presentations, especially those from Boddy, Grüner, Mishra and Moore highlighted the importance of reflecting on emotions in research. Art is emotion; it is, to paraphrase Benjamin Myers, the desire to cast the moment in amber. Ayala Levin's master class (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger)

Ayala Levin's master class (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger) The gd:c summer school takes a field trip to the Museum Fünf Kontinente. (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger)

The gd:c summer school takes a field trip to the Museum Fünf Kontinente. (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger) One, yet many (but not too many). (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger - the author in the back left with the snappy Hawaiian shirt)

One, yet many (but not too many). (Image: Annalena Labrenz & David Grillenberger - the author in the back left with the snappy Hawaiian shirt)

Image:

Image:  Image: KHK global dis:connect collection

Image: KHK global dis:connect collection

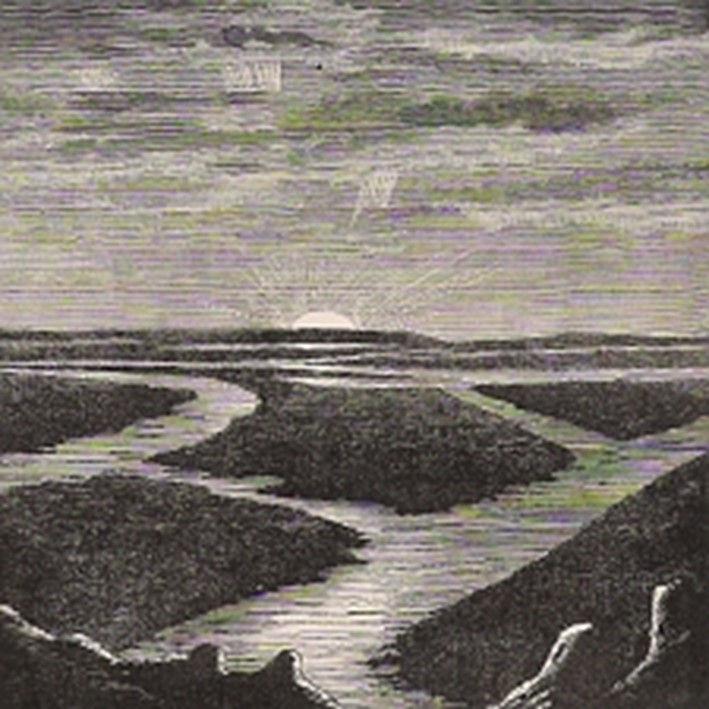

A depiction of the imagined system of canals on Mars. Title of Cosmopolitan Magazine XLIV, 4 (March 1908). https://www.loc.gov/item/cosmos000114.

This theory about life on Mars featured prominently in the discussion around 1900 about whether the new wireless communication technology could be used to communicate with extra-terrestrial beings — a discussion electrified by pioneers of that technology, like Nikola Tesla and Guglielmo Marconi, as well as the keen interest of the press. Already in 1892, Flammarion was convinced that the prospect of communicating with extra-terrestrials was ‘not at all absurd’.

A depiction of the imagined system of canals on Mars. Title of Cosmopolitan Magazine XLIV, 4 (March 1908). https://www.loc.gov/item/cosmos000114.

This theory about life on Mars featured prominently in the discussion around 1900 about whether the new wireless communication technology could be used to communicate with extra-terrestrial beings — a discussion electrified by pioneers of that technology, like Nikola Tesla and Guglielmo Marconi, as well as the keen interest of the press. Already in 1892, Flammarion was convinced that the prospect of communicating with extra-terrestrials was ‘not at all absurd’.