In

Blog, Blog 2024

christopher balme

‘While, biologically speaking, the idea of individual human races with different origins is as farcical as the medieval belief that elves cause hiccups, the social reality of race is undeniable’. Henry Louis Gates Jr.[1]

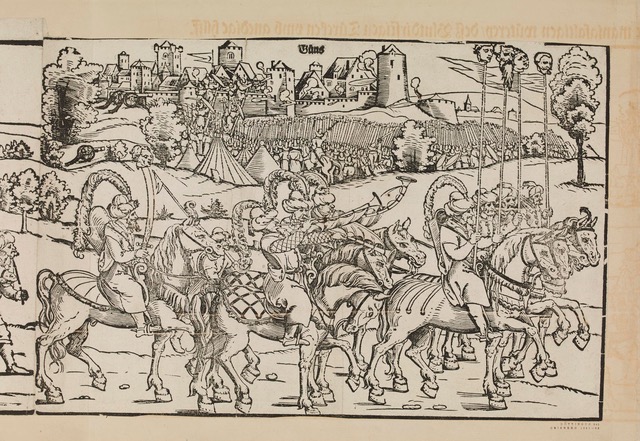

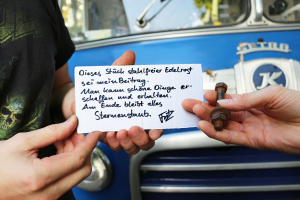

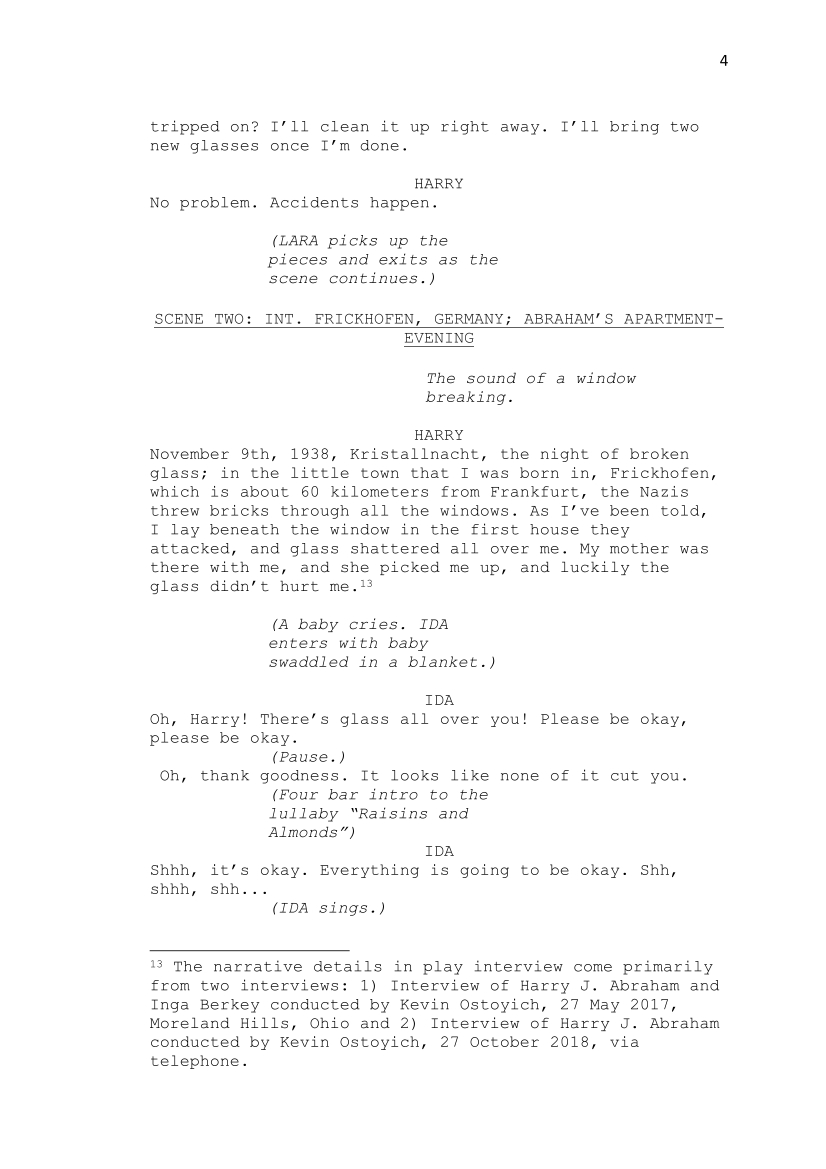

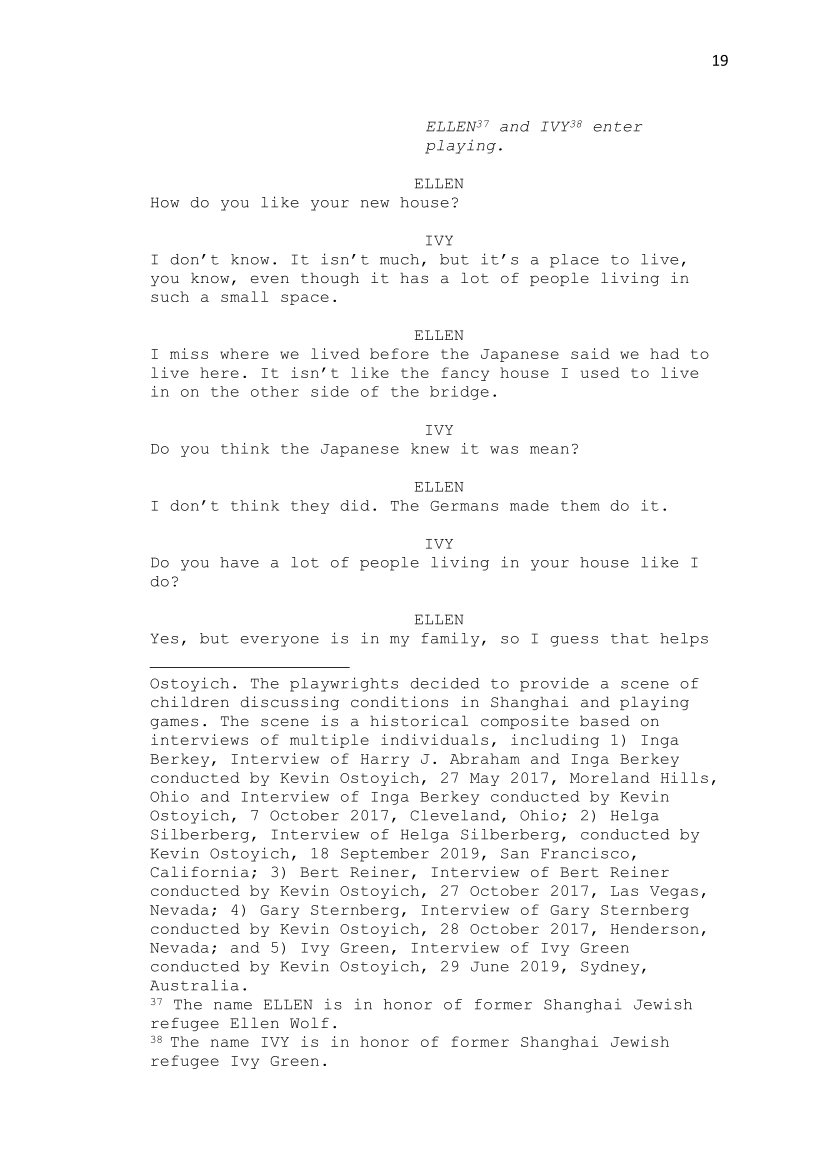

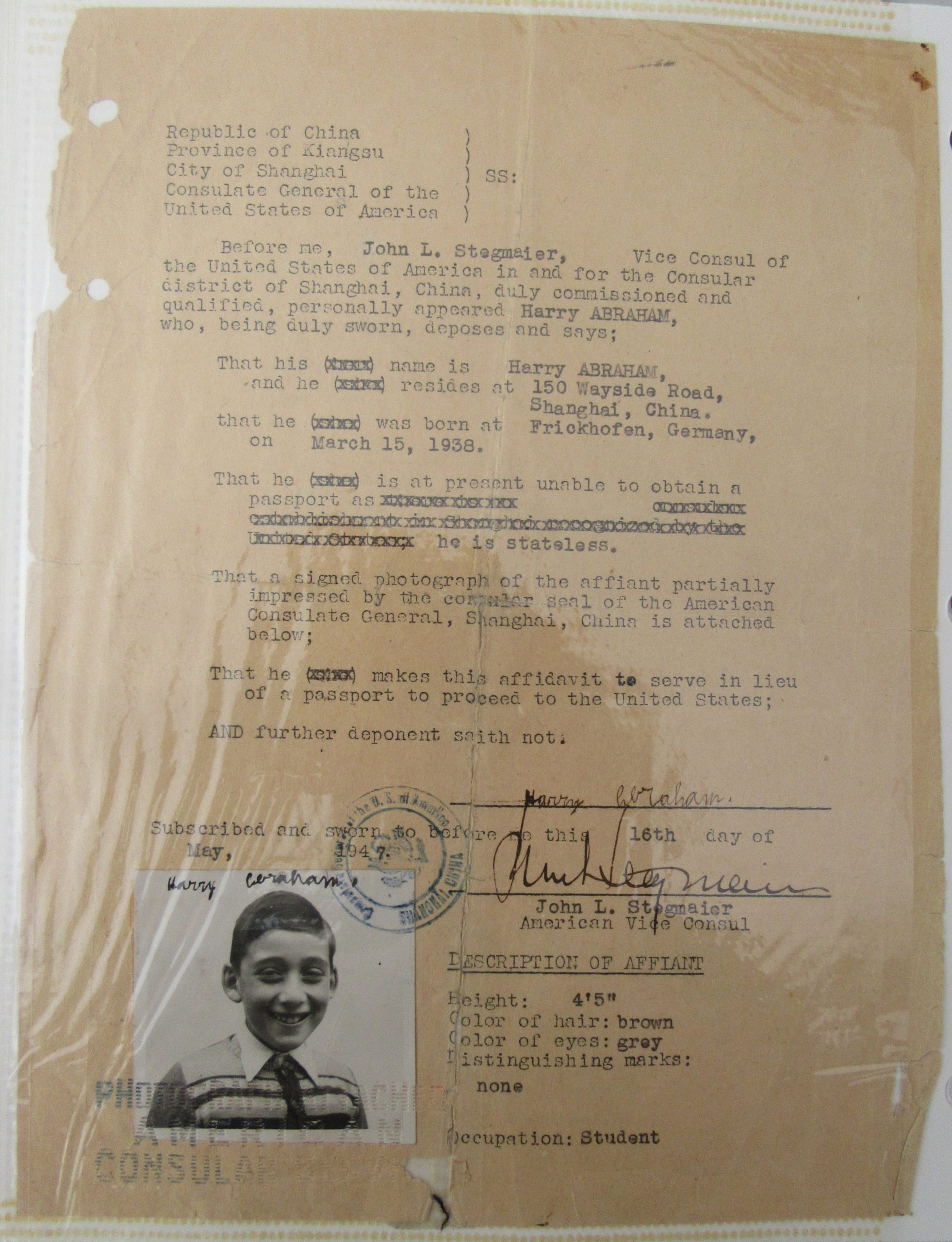

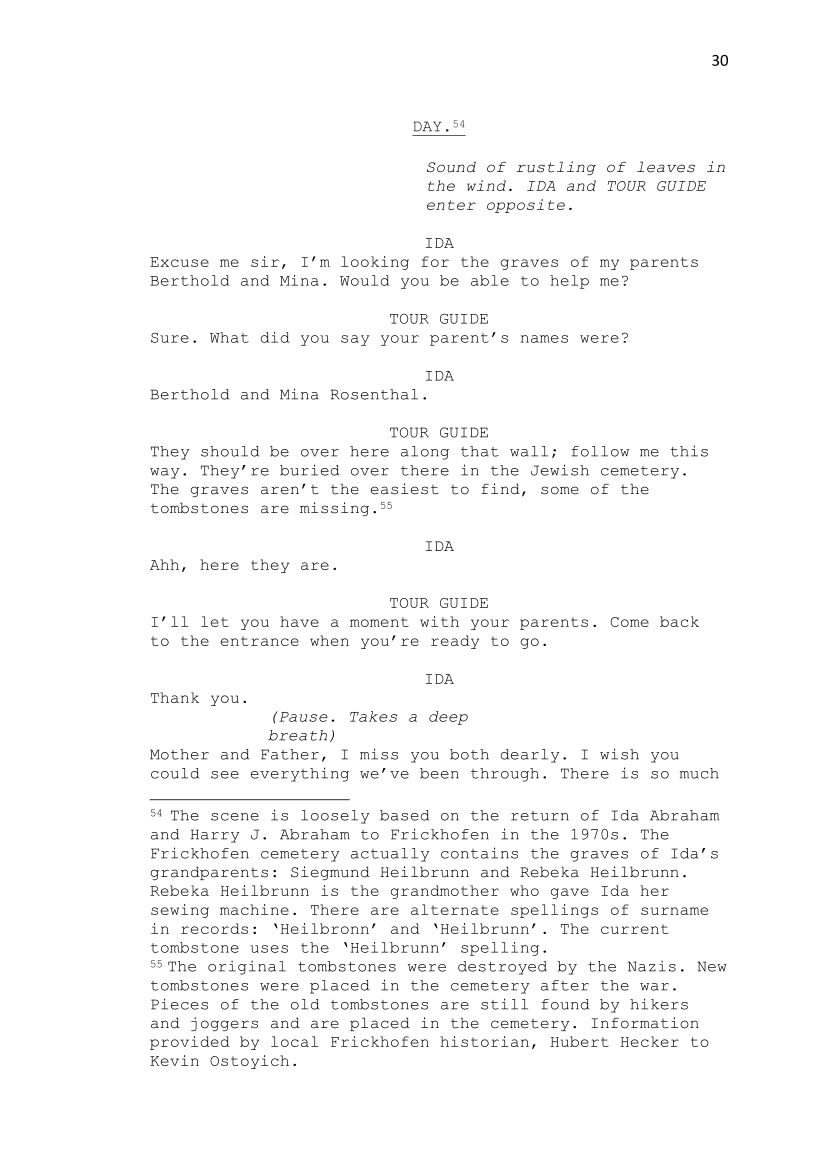

Fig. 1: 7. A mid-19th century illustration of Blumenbach’s five-part taxonomy with the addition of colour terminology. Note that the category ‘Caucasian’ extends well into the Indian subcontinent. Note also the spelling of the word Race in German. (Source: Johann Georg Heck, Bilder-Atlas zum Conversations-Lexikon: Ikonographische Encyklopädie der Wissenschaften und Künste. Vol.1. Leipzig: Brockhaus, 1849, plate 43).

The US Supreme Court decision to severely restrict affirmative action at two US universities generated strong reactions in the US. It was also widely reported in German media.

[2] The core question was summarised in the ruling: ‘Admission to each school can depend on a student’s grades, recommendation letters, or extracurricular involvement. It can also depend on their race’.

[3]

But how do you render the most important concept in the ruling – race – when the most appropriate German word,

Rasse, is verboten? It is the ‘R word’ in German. How do you report on a ruling containing ‘race’ in various permutations – race-conscious, race-sensitive, etc. – over 800 times?

You find approximations, which always mean something different. The

Süddeutsche Zeitung opted for ‘skin colour’ (

Hautfarbe), another paper used ‘

Abstammung’[4] and a third (

Spiegel Online) proposed

Ethnizität.

[5] So, depending on the paper you were reading, the ruling addressed admission practices that considered either skin colour, ancestry or ethnicity. The terms are different, but they are linked by putative biological determinants pertaining to applicants but beyond their control. For German readers unfamiliar with US universities, it sounded odd that skin colour was a criterion for admittance to one of the world’s most famous universities.

My interest is less in the ruling than in looking at the word

race from a dis:connective perspective. Although advocates of the term claim it is a ‘global concept’, it is in fact being kept alive by Anglosphere scholars and activists responding to local contexts.

[6]

Globalisation does not just apply to transport, trade and economics but also to concepts. The refusal of the German-language media to use the German word for

race indicates significant differences.

Is it not time to consign the English word

race to the dustbin of our vocabulary, as is the case in German? Or is the German objection to its version an outlier explicable through its history, which needs to be realigned with US American usage? At a time when discriminatory language is so rifely policed, why is

race still in circulation? The latter question has become the leitmotif of all critiques of the concept.

[7] So why again? Put simply,

race is

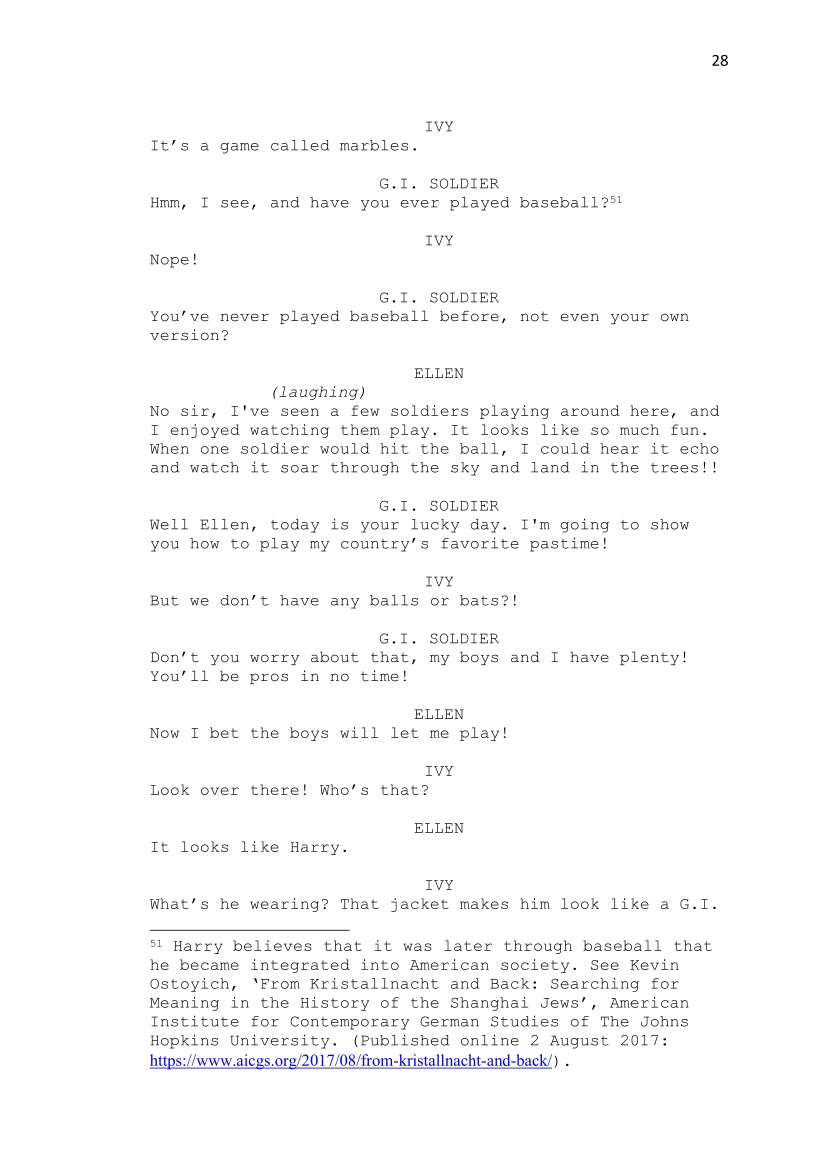

also a problem of language use: it exists primarily in the speech act. Or, to paraphrase Henry Louis Gates, while the concept of race might be from the land of fairy tales, its uses create realities.

This essay is divided into three sections: firstly, a brief review of the state of the art in both languages. In part two, we will see how the word has largely disappeared from German. The third part of my paper will analyse language use, contrasting the performativity of the word in both languages. I propose a new linguistic category – affectives – to designate its function. Affectives are a special category of stand-alone words that have the force of speech acts without being embedded in propositional structures, like

race and

Rasse.

The paradox of race

The paradox of the race concept dates at least to the 1940s. Put simply, and citing evolutionary biologist, David Reich: ‘In 1942, the anthropologist Ashley Montagu wrote

Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race, arguing that race is a social concept and has no biological reality, and setting the tone for how anthropologists and many biologists have discussed this issue ever since’.

[8] A similar critique was, however, published four years earlier by Magnus Hirschfeld in his book,

Racism, which, although written in German, was first published in English and represents, if not the earliest, certainly the first thorough discussion of the term

racism, which, deconstructs the biological precepts underlying

race.

[9]

Despite this lack of ‘biological reality’, the word continued to be used in everyday speech, official documents, censuses and opinion polls. Henry Louis Gates revisited the paradox in 2022 in an op-ed for the

New York Times entitled

We Need a New Language for Talking About Race. Gates and his co-author Andrew S. Curran begin with an anecdote from the classroom:

The other day, while teaching a lecture class, one of us mentioned in passing that the average African American, according to a 2014 paper, is about 24 percent European and less than 1 percent Native American. A student responded that these percentages were impossible to measure, since ‘race is a social construction’.[10]

They continue: ‘the fact that race is a social invention and not a biological reality cannot be repeated too much. However, while race is socially constructed, genetic mutations — biological records of ancestry — are not, and the distinction is a crucial one.’

[11] Neither Gates and Curran, nor the authors of the article mentioned use the term

race, the student just assumed that is what they were talking about.

[12]

Their call for a new language of ‘race’ is predicated on the term

ancestry – a shared genetic history that should be ‘taught in our classrooms’. I want to remain with the student’s phrase ‘race is a social construction’ as it is the standard definition of

race today.

To resolve the paradox between a discredited biological definition and a mainstream culturalist understanding of the term, I asked Chat GPT what it/they thought about the paradox. The answer was characteristically nuanced:

The concept of "race" has been discredited as a biological concept, but it still persists as a social construct with profound implications for people's lives and experiences. The term "race" is still widely used because it continues to be a powerful tool for social categorization and for understanding and explaining social inequalities and power relations. [13]

In other words, continued use of ‘racial’ categories and

race to differentiate and discriminate gives meaning to people’s identities. To understand how this use is itself aporetic, we need only look at the US Supreme Court ruling cited above. The court ruled on an action brought by the Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., which claimed that ‘race-based’ admissions policies at Harvard and the University of North Carolina contravened the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the US constitution.

The ruling accentuates the aporetic nature of

race/

racial wittingly and unwittingly. Wittingly, in the passages detailing the imprecision and contradictions in the universities’ classifications:

the universities measure the racial composition of their classes using the following categories: (1) Asian; (2) Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander; (3) Hispanic; (4) White; (5) African-American; and (6) Native American. (…) the categories are themselves imprecise in many ways. Some of them are plainly overbroad: by grouping together all Asian students, for instance, respondents are apparently uninterested in whether South Asian or East Asian students are adequately represented, so long as there is enough of one to compensate for a lack of the other. Meanwhile other racial categories, such as ‘Hispanic,’ are arbitrary or undefined.[14]

But the judgement also appears unwitting, applying the central term

race over 800 times without defining it.

[15]

Both the universities and the chief author of the ruling, Justice Roberts, apply the same arbitrary principle. Roberts reproaches the universities for using ill-defined taxonomic criteria: ‘The universities’ main response to these criticisms is, essentially, “trust us”’. This amounts to ‘I know it when I see it’ applied to race.

[16] However, Roberts never questions the concept itself, only the subclassifications applied by the universities. Perhaps a more granular application of categories might have strengthened their case or, conversely, invalidated the classification system when too many subcategories were adjudicated. How would one distinguish South Asians from East Asians? There is a conflation of

definiendum and

definiens. There exists something called ‘race’, which is a category that universities should not apply when admitting students, but it needs no definition.

This ruling is symptomatic of the state of affairs in the anglophone world, in which the USA is perhaps most attached to the term, but it is applied throughout Anglosphere with little awareness of its paradoxical nature.

In the UK, the term ‘ethnicity’ has largely replaced ‘race’ as the preferred term of differentiation. For example, when applying for a job, applicants are often requested to note their ethnic affiliations. While ethnicity is certainly more differentiated than ‘race’ (Harvard identifies six ‘races’), in its application it encounters the same problems as the latter as an administrative and bureaucratic category.

In order to give up the use of ‘race’ like smoking, we need to turn to Germany, which has almost kicked the habit.

The return of Rasse

The German word for race,

Rasse, has largely disappeared from public discourse, except in reference to animals where it means

breed (Fig.2). No official document will ever ask about your

Rasse, but certainly your religion, marital status and nationality (and your ‘migration background’, a euphemism for non-German descent). This disappearance is not linked to any significant semantic differences; in fact,

race and

Rasse both derive from the French term

race.

The difference between use and reference matters here. As a historical term it is acceptable when used retrospectively (say for the Nazi period or South Africa under Apartheid). But on its own,

Rasse has become a ‘pejorative fiction’, a term that has ‘null extensionality’, that lacks an empirical referent.

[17] German-speakers once thought

Rassen to exist, like dragons and unicorns, but the category has fallen out of reality.

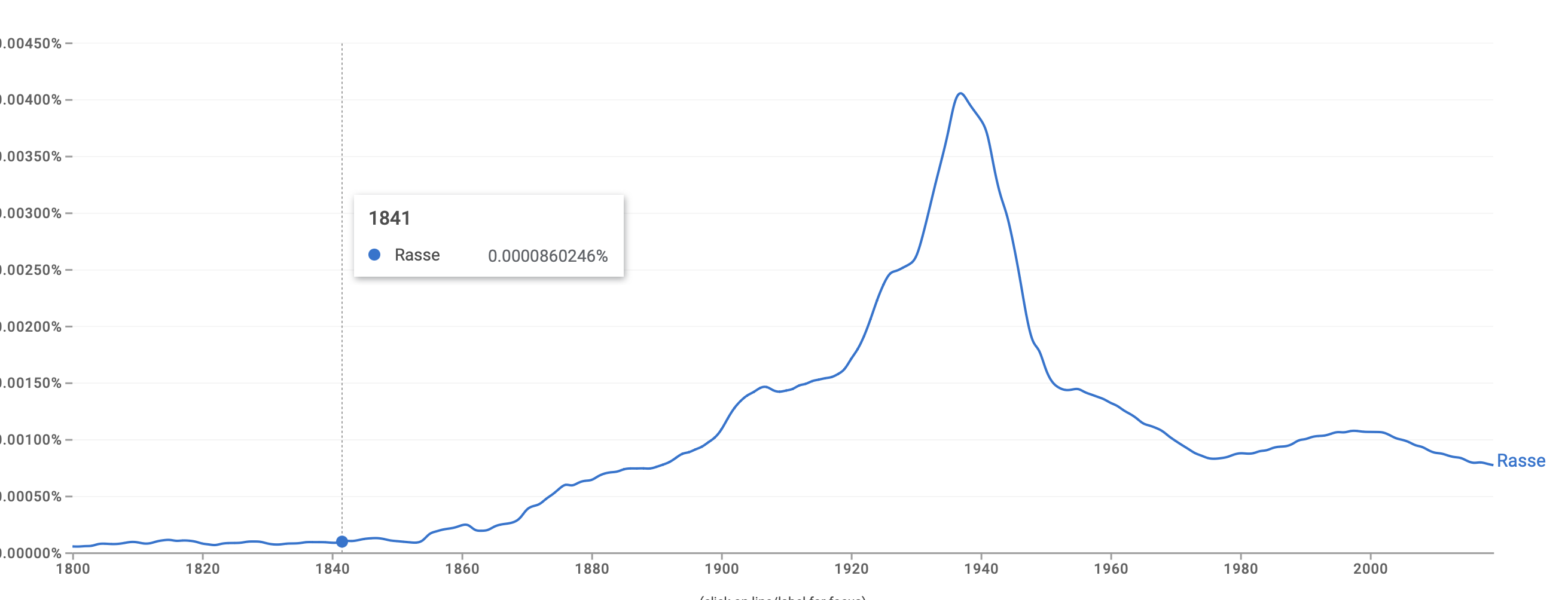

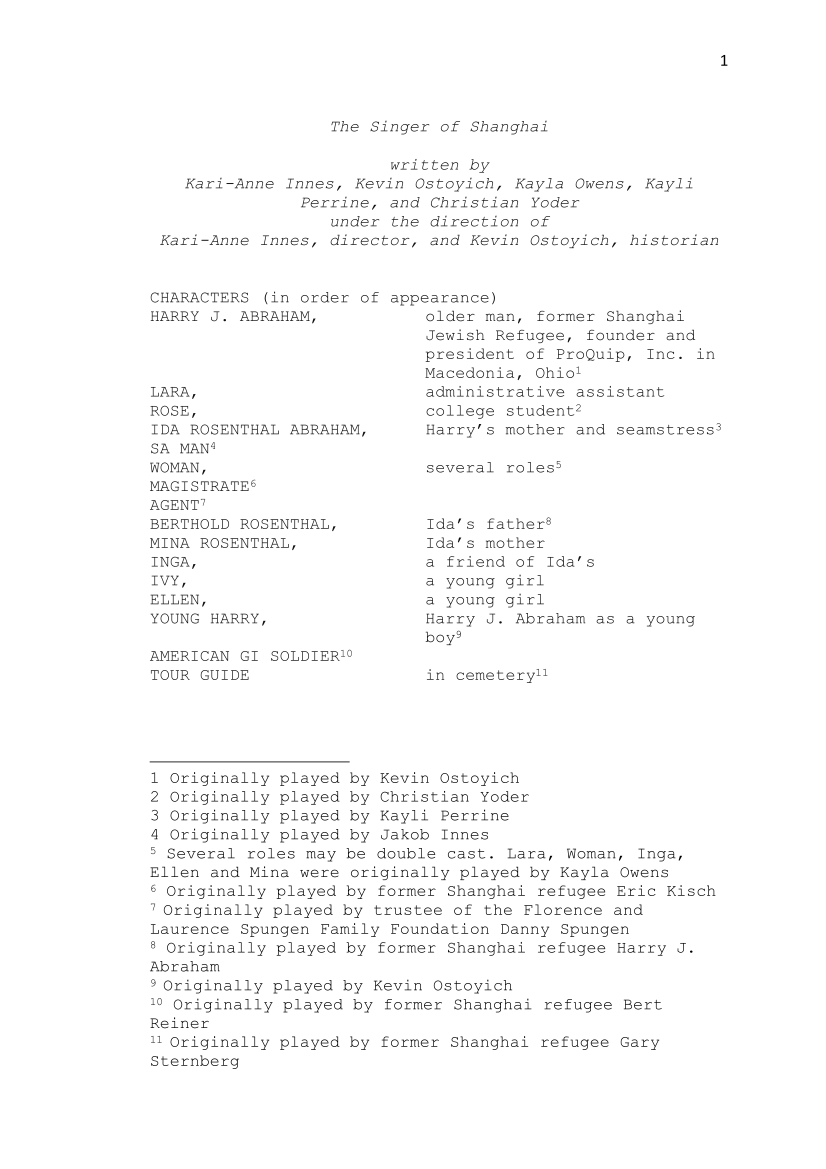

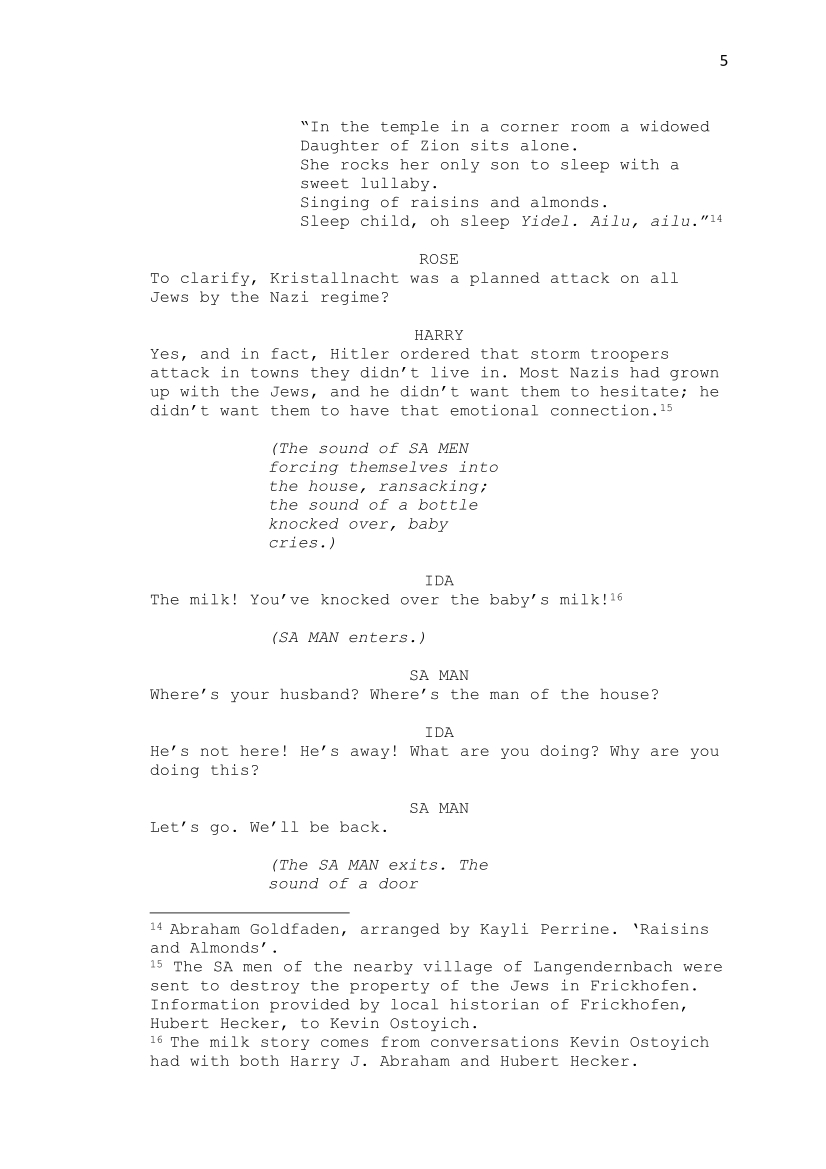

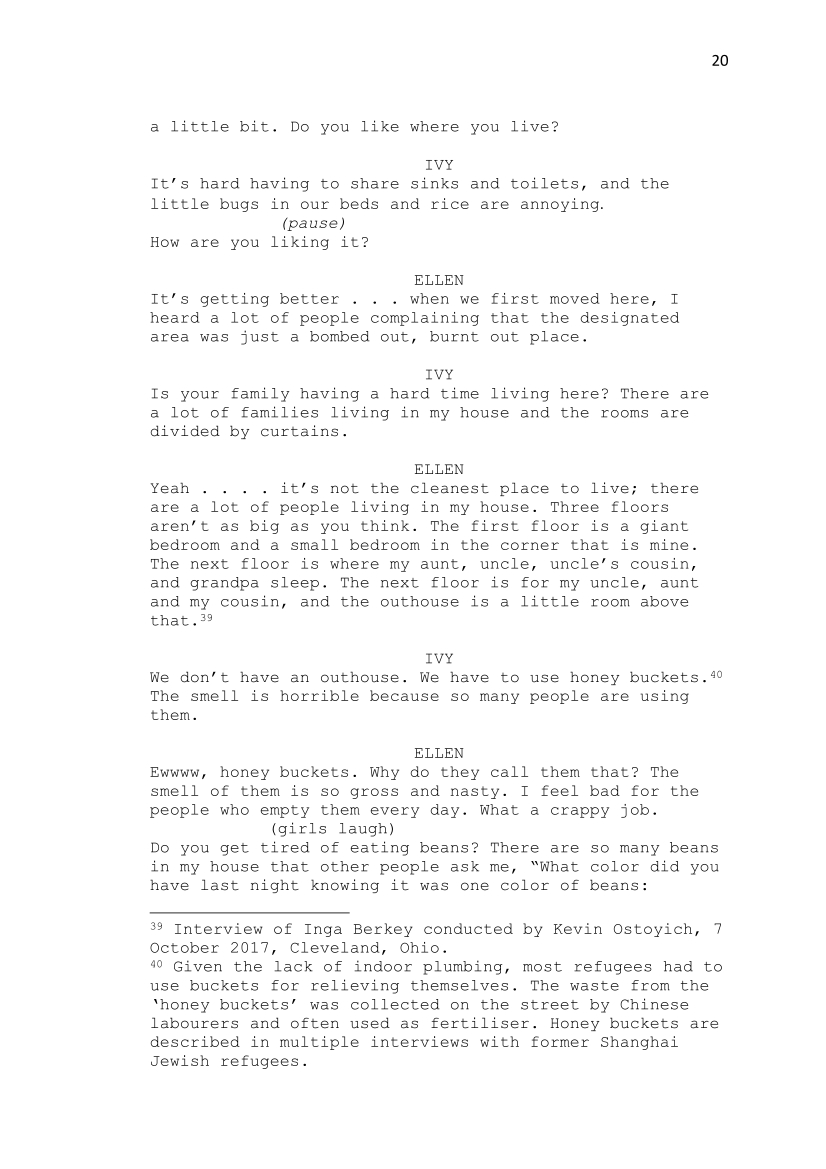

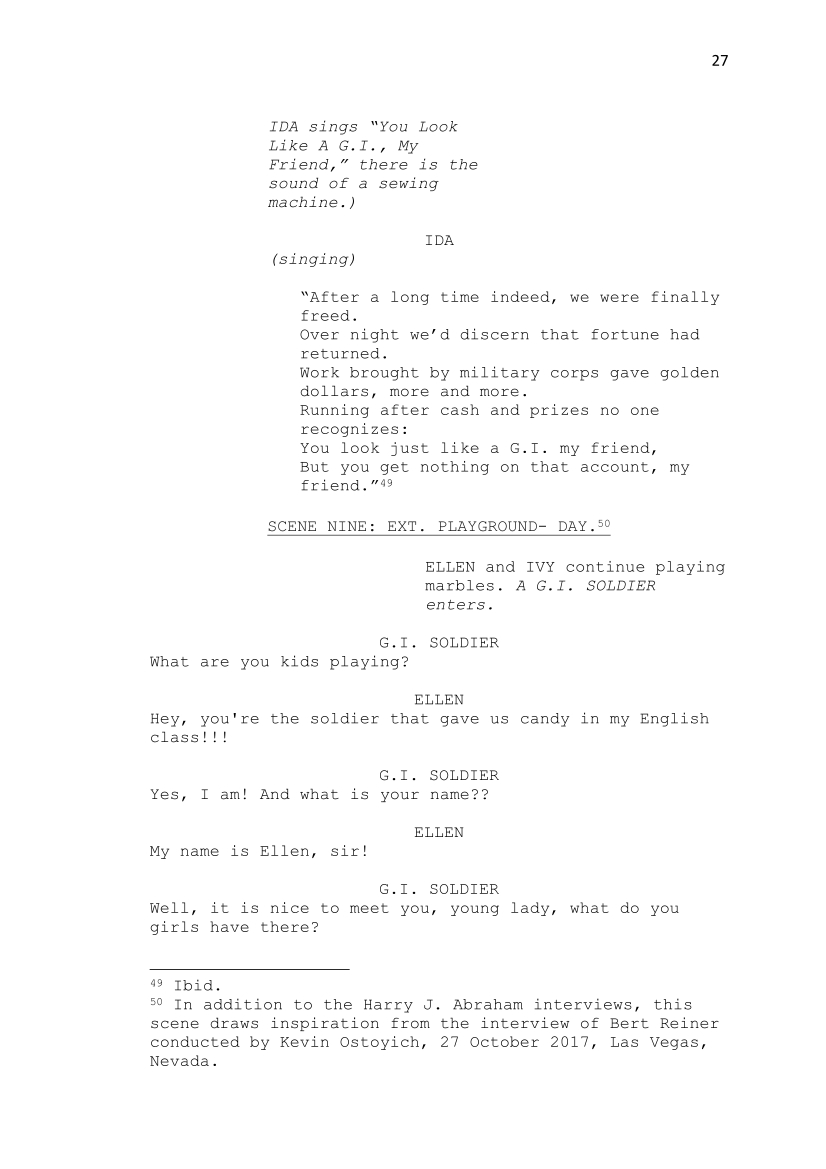

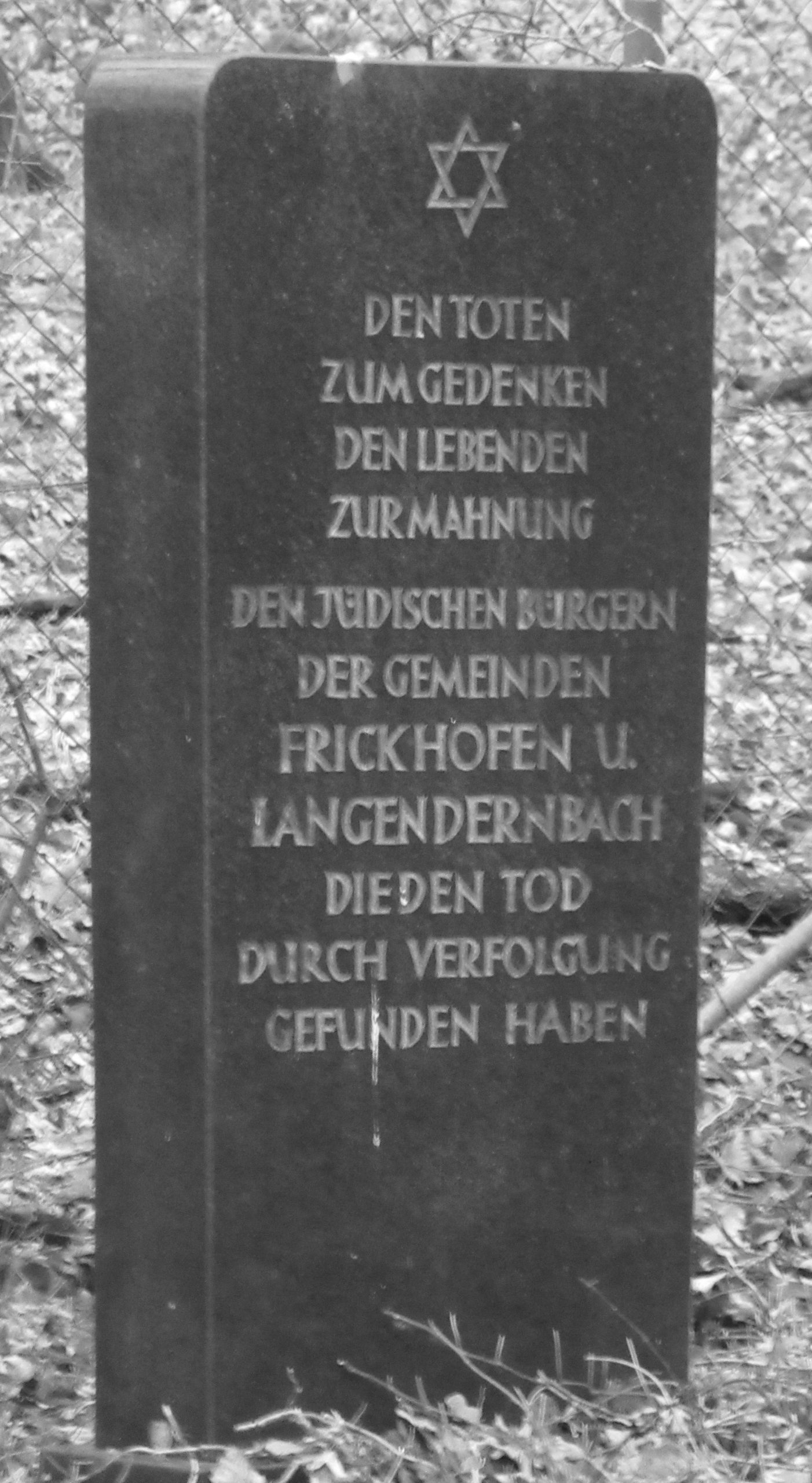

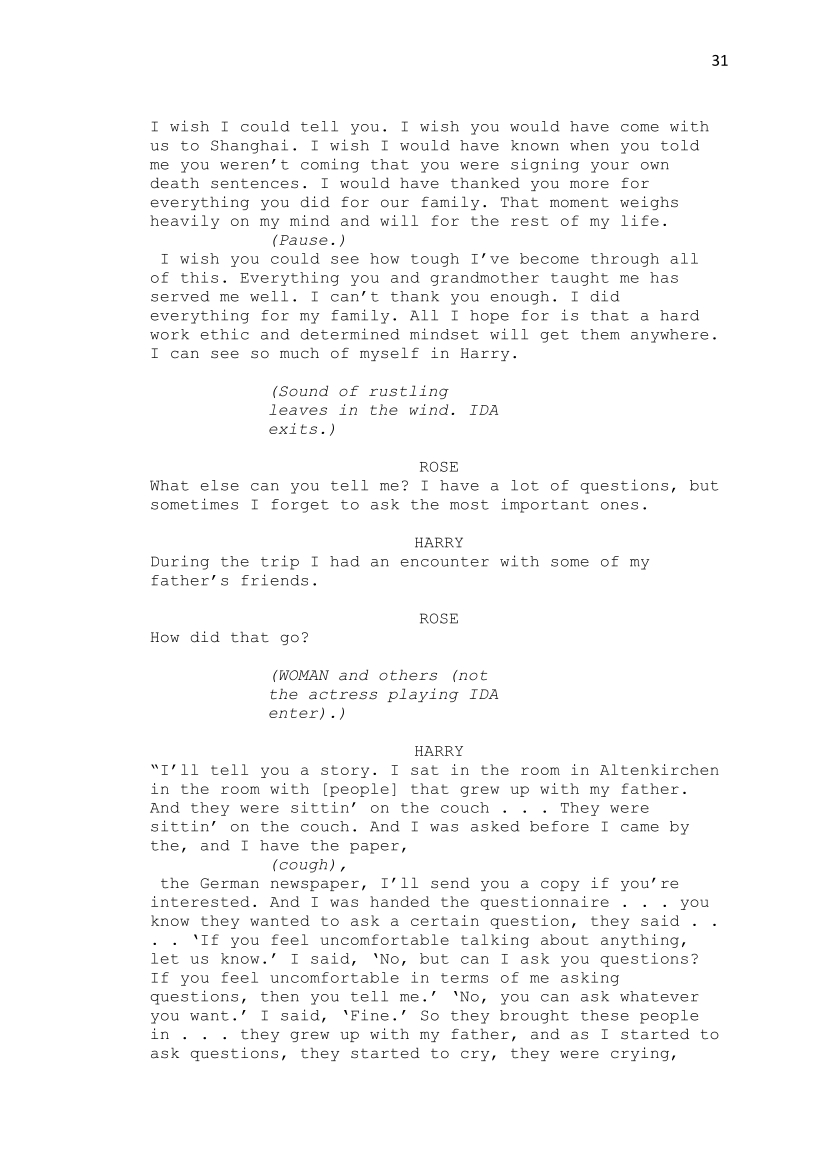

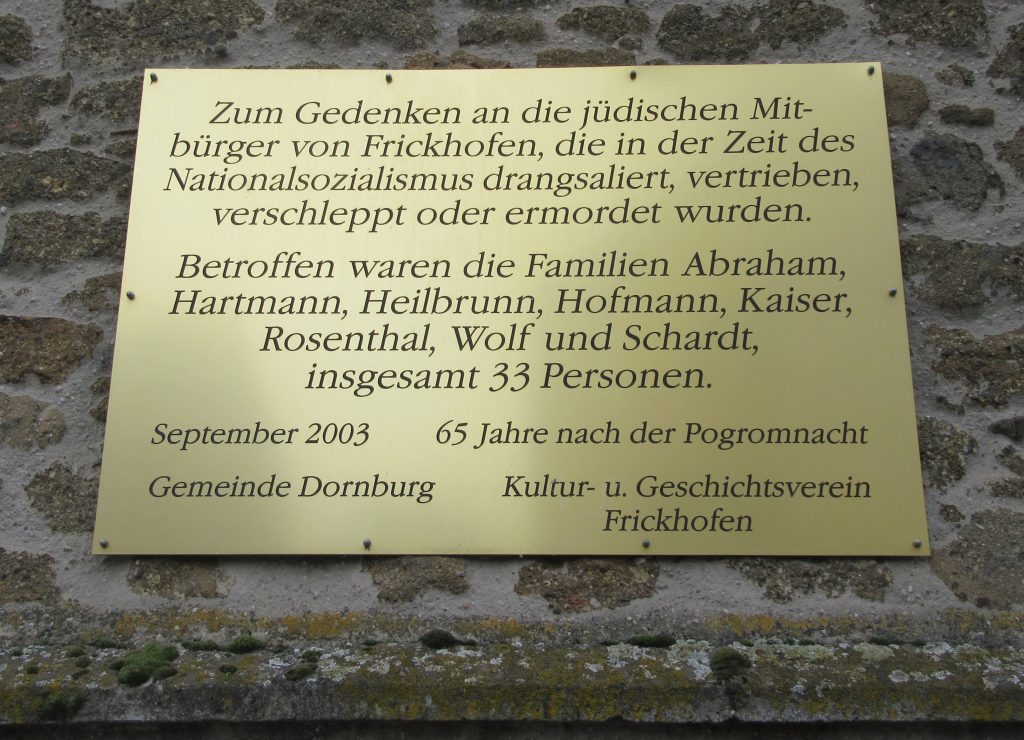

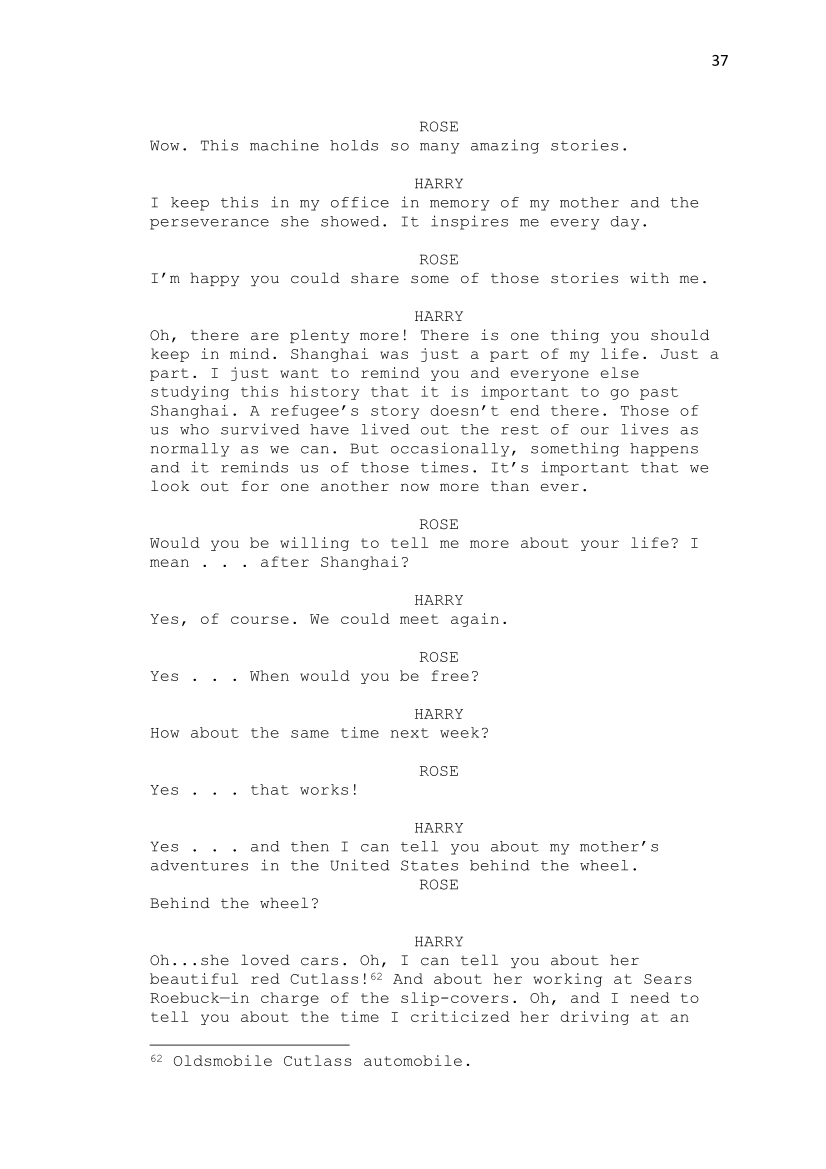

Fig. 2: Decline in the use of the word Rasse in German-language books. Source: Google ngram.

The disappearance of

Rasse has not been adequately described sociolinguistically, but the reasons are obvious. It is now a pejorative term; it is a ‘bad word’. This sometimes confounds anglophones when translating

race with

Rasse, as suggested by a policy paper by the German Institute for Human Rights (GIHR):

‘Und welcher Rasse gehörst du an’? It also leads to the situation described above when German newspapers scrambled for ‘good’ words to report on the US Supreme Court ruling.

This disappearance was not decreed by the government but rather results from disuse. Consequently, the German Institute for Human Rights has sought to get the word removed from the German constitution and some other laws. The German

Grundgesetz (Basic Law) is the most prominent law that retains the word. Article 3(3) reads: ‘No person shall be favoured or disfavoured because of sex, parentage, race, language, homeland and origin, faith or religious or political opinions’.

[18]

According to the GIHR, this ‘leads to an unresolvable contradiction’:

according to the current wording of the article, in the case of racial discrimination, those affected must claim to have been discriminated against on the basis of their ‘race’; they must virtually classify themselves as belonging to a certain ‘race’ and are thus forced to use racist terminology. (…) even though the term "race" is not open to any reasonable interpretation. Nor can it be, since any theory based on the existence of different human "races" is inherently racist.[19]

The last days of the previous grand coalition (2018-2021) saw an attempt to change the wording through a cross-coalition alliance and replace

Rasse with

racism, but the Christian Democrats prevented it, claiming they needed ‘more time’ to think.

[20]

Debate was framed by a discussion that produced an unusual coalition between lukewarm Christian Democrats, an emphatically opposed alt-right party and the ‘progressive’ left. Most puzzling is the agreement between the left and extreme right. An example of the ‘progressive’ argument was published by two young legal scholars, Cengiz Barskanmaz from the Max Planck Institute for Anthropology in Halle and Nahed Samour, from the Humboldt University in Berlin:

It is only through such a term [Rasse] that racism, i.e. discrimination on the basis of race, becomes nameable and addressable. The legal concept of race is a necessary instrument to be able to address racism (including anti-Semitism) in terms of anti-discrimination law [...] Erasing the term negates historical and contemporary inequalities and risks trivialising them. […] This approach is part of Critical Race Theory, which is precisely a response to white jurisprudence […]. Black legal scholars demand race as a central category of analysis.[21]

The authors argue that the concept of race is not only a legal term but is an important ‘global concept’ in the social sciences – a concept that in turn is used by jurisprudence. The authors resist attempts to ‘blur’ the distinction between ‘race’ and ‘racism’:

Race is in the world, the socialisation of us all, the perception of this world, is racialised. Race does not exist, but it has an effect. […] It would seem grotesque if, after the murder of George Floyd, we told our US colleagues that our lesson was to erase the discriminatory factor of race.[22]

So Germany should retain

Rasse, at least in its legal documents, perhaps elsewhere, as a

Mahnmal (memorial) to its history and to show solidarity with US colleagues. Ultimately, they argue for a stronger, more prominent representation of the word

Rasse, which implies reintroducing it into public discourse.

Perhaps the key lies in these somewhat contradictory sentences: ‘Race is in the world, the socialisation of us all, the perception of this world, is racialised’ and ‘Race does not exist, but it has an effect’. In English the first sentence is unremarkable: ‘The perception of this world is racialised’. This is a standard statement of the ‘race is a social construct’ tradition. In German, however, the word

rassialisiert creates a different effect. It sounds simultaneously neologistic – not (yet) part of everyday German usage

[23] – and anachronistically Nazi, as the Nazis created many compound words based on

Rasse, which are today all pejorative. Its use in this text signals an attempt to introduce Critical Race Theory vocabulary into the German context, though its effect is either incomprehension or resistance. After decades of ‘re-education’, which involved ridding German of Nazi vocabulary, it is challenging for many Germans to understand that Critical Race Theory advocates reactivating racial thinking and even resegregation in some institutional contexts.

[24]

The second sentence – ‘Race does not exist, but it has an effect’ – is paradoxical. To make sense of it, we need the philosophy of language.

Affectives

‘the meaning of a word is its use in the language’ (Wittgenstein, §43 Philosophical Investigations)[25]

J.L. Austin’s

How to Do Things with Words is among the most influential philosophical texts of the 20th century. My argument is indebted to Austin, not because the words

race or

Rasse are performatives but because Austin’s approach to language can help understand the paradox before us. This section asks what happens to a word when, on the one hand, embarrassment leads to its disuse, and on the other, it is used excessively despite an atrophied conceptual and scientific meaning. I argue that the word in both languages has the same status; it has become an ‘affective’.

Similar to Austin’s performatives, affectives are words that generate emotions. They are usually nouns, sometimes adjectives, seldom verbs. Their mere enunciation, often without the contextualisation of a sentence, can evoke strong emotions, focus administrative minds and even influence politics. In their stand-alone power, their emotional effect outweighs the semantic aspect. Yet there is no grammatical description of such words. According to linguistic philosophy, affectives would belong to the category of ‘expressives’: words or statements that convey speakers’ attitudes to a referent.

Affectives have perlocutionary force. Austin divides any speech act into three parts: locution (its meaning); illocution (the execution of an action by uttering the sentence); and perlocution ‘the achieving of certain effects by saying something’.

[26] Affectives are primarily perlocutionary because, in the case of

race for example, the locutionary meaning is so unstable.

While

affective as a noun is new, the class of words is not, even though they seem to be proliferating. Examples of old affectives include

blood,

popery,

liberty,

fascism and

communism. New affectives might include

globalisation,

neoliberal and

capitalism – the list is dynamic. It changes as words gain and lose emotive power. Censors have long implicitly recognised affectives’ power in their lists of proscribed words.

[27]

The growing number of one-letter words – the n-word, the p-word and I would like to add the r-word – testify to affectives’ growing importance. One-letter words are extreme examples, words that dare not speak their names. And while all slurs are affectives, not all affectives are slurs.

[28]

Affectives can necessarily stand alone. Just enunciating the word by itself will usually create its effect. Hence, they are closer to expletives than performatives, which require a sentence and the right conditions to function.

While one expects to encounter affectives in political contexts, a recent development that interests me in the discussion of

race, is the use of affectives in scholarly-academic discourse, where they often masquerade as concepts. Or, more accurately, in academic contexts many terms are

transitioning from concepts to affectives. A word like

colonialism has reasonably clear conceptual boundaries for historians, but it is increasingly an affective among scholars. The same applies to

capitalism: in certain contexts, its enunciation generates an affective, negative response.

There is also a trend towards double affectives to generate additional emotive power. An example would be the current use of

racial capitalism or

settler colonialism. These terms, because they are relatively new, have emerging conceptual boundaries. They are serious academic concepts but are increasingly used also as affectives to signal a history of injustice. Affectives position the user in a particular ideological context and often nudge the addressee to conform by force of emotive appeal or the desire to join a scholarly community.

Affectives can also happily accommodate antithetical meanings. The epithet

socialist as a noun or adjective can be a badge of honour, especially for a British academic, while it functions as an invective in most US political contexts. What links the extremes is the word’s affective appeal.

The German

Rasse is an affective whose enunciation can cause discomfort, even embarrassment, rather than anger or outrage (the default affect of our times). As soon as a suffix or prefix is added, the word loses some affective force.

Rassis-mus or

Rassen-politik are not affectives because they contain a level of observation or abstraction than weakens the affective charge.

While

Rasse is clearly an affective,

race is still in transition. However, I argue that, while it is residually a concept in its redefinition as a social construct,

race is used increasingly as an affective. This derives from its almost total synonymity with

racism.

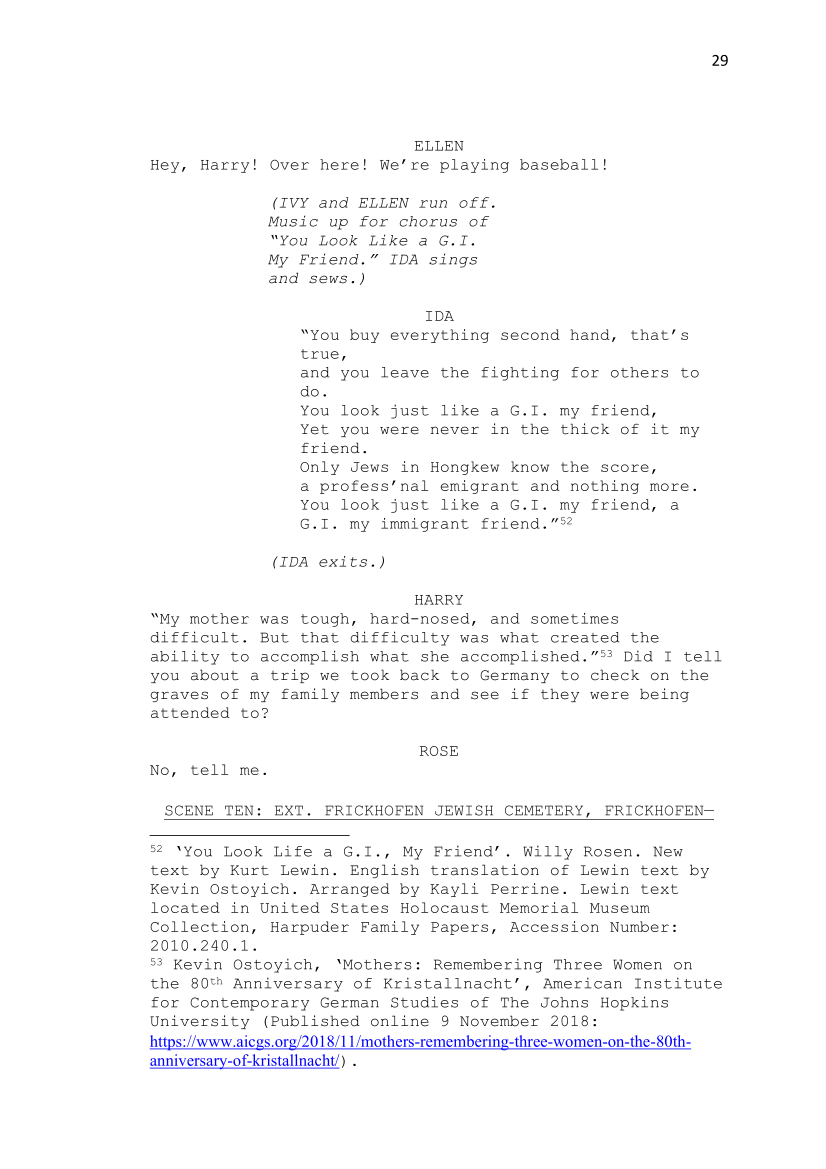

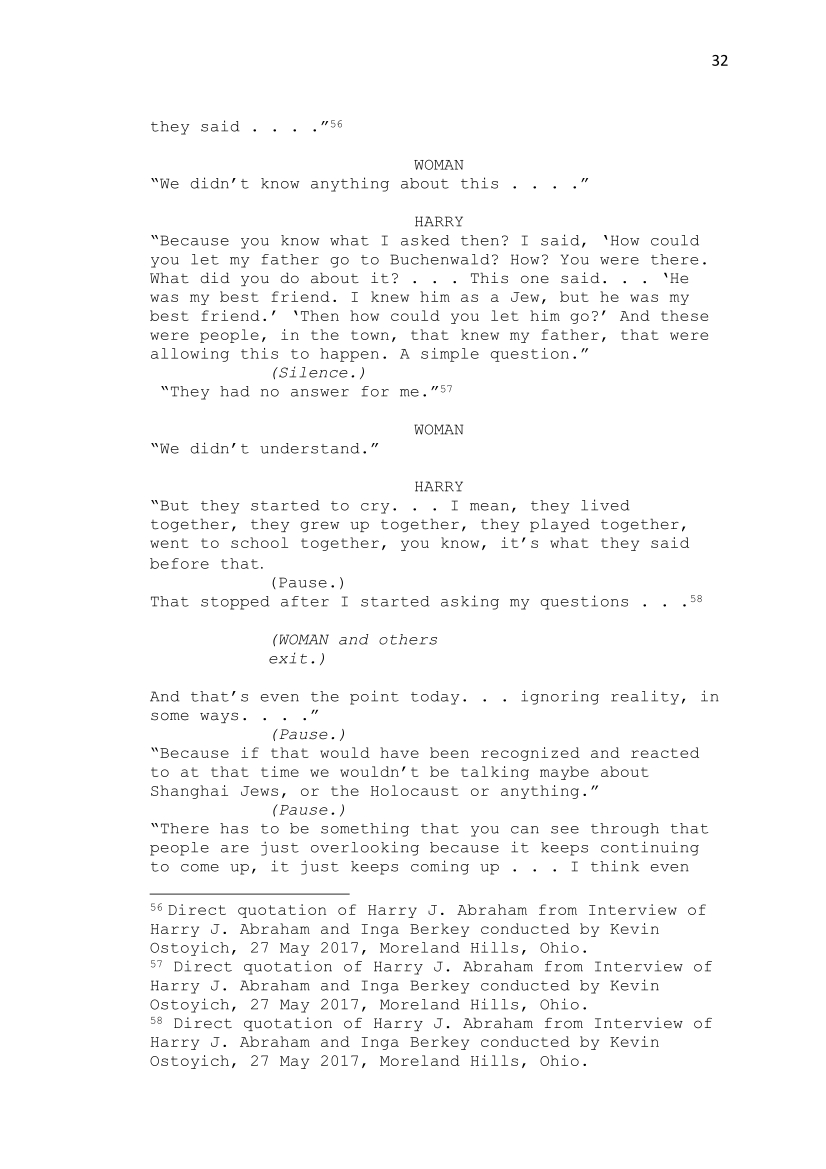

As the 2021 Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities in the UK makes clear, a discussion of the ‘language of race’, a subheading in the report, is in fact a discussion of racism; the two terms are used interchangeably.

[29] The granular analysis of social disparities in the report pinpoints ethnic not ‘racial’ categories, distinguishing Black African, Black Caribbean, Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi ‘ethnicities’ (and white ethnicities as well). The report also uses the qualifiers

racial and

ethnic interchangeably until they become synonyms. Even the title itself is ambiguous: is race a qualifier of disparities or is it a separate topic next to ethnic disparities? In this title

race functions as an affective, while

ethnic disparities constitute a proposition.

Fig. 3: Cover of Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities.

In academia,

race usually references racism and discrimination. ‘It’s all about race’ is a statement where the noun is an affective. The referent is, however, probably racism and discrimination, not the outdated taxonomic theory of differentiating the human species. However, the latter, the biological residue, as Stuart Hall argued, clings to the new meaning. The semantic instability of

race is counteracted by its emotive signalling. Affectives are thus dynamic, gaining and losing emotive charge over time.

Within the category of affectives,

race, unlike

Rasse, is still a dual-use word, emotive and conceptual, whereby the conceptual aspect is paralysed by the paradox, as the underlying taxonomy has been discredited and the categories to which it ostensibly refers appear increasingly unfit for purpose. If analysing disparities in income, education or health outcomes is the object, then differentiation by ethnicity is the more precise analytical tool.

But are affectives speech acts? No and yes. In the precise technical sense defined by Austin and expanded by Searle, probably not because they lack the illocutionary component which depends on verbs. Affectives are speech acts, not in the individual utterance, but through the force of repetition. Paraphrasing John Searle: The aim is not to represent reality but to change reality by getting reality to match the content of the speech act, the representation.

[30] The classic performative does this simply by uttering the right combination of words within a correct set of conventions.

Through repetition affectives can achieve similar perlocutionary effects. There are no such things as human races, plural, but uttering

race enough times and with enough emotive force can will them back into existence. It is not that we know races when we see them, but we reify them by saying them.

Conclusion

The decline of race as a scientific-biological concept and its re-emergence as a social construct in the Anglosphere means that the latter understanding of the term is currently received wisdom. The word’s semantic contradictions were adumbrated by Stuart Hall to the point where he suggests, in jest, to give up the term like smoking. This suggestion is no laughing matter in Germany where the word

Rasse has largely disappeared from public discourse because it is intuitively recognised as a proscribed term. Its advocates reside at opposite ends of the political spectrum, where anti-racist activists and right-wing conservatives both support the word’s retention in the German constitution, where it is rather an embarrassment.

The struggle over antithetical meaning(s) should end in semantic exhaustion, but this is not the case.

Race is being used more than ever in the Anglosphere. Part of this ‘success story’ is due to sheer repetition; by using the word, we don’t just naturalise it, we enable its continuing existence. However, today its use is primarily affective, not conceptual. Comparing

race and

Rasse demonstrates that, although the words are etymological siblings, their affective power is antithetical. In English

race is on the one extreme a mobilising call for resegregation (‘embrace race’); in German the word is unequivocally pejorative.

Such terms belong to a category termed here

affectives. These words have the force of speech acts in their ability as stand-alone terms to generate emotions and even create communities of adherents and opponents. While affectives have always been used in politics from placards to pamphlets to censorship, the new situation is in academic discourse, where affect is rivalling or even displacing concept. When scholars write

race, they are usually referencing discrimination, in which case

racism is more precise. Using race in any other context is probably for affective, not analytical purposes.

Race naturalises racism because it reasserts the word’s biological traces.

[1] Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Andrew Curran, 'We Need a New Language for Talking About Race',

The New York Times (New York) 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/03/opinion/sunday/talking-about-race.html.

[2] Fabian Fellmann, 'Historisches Urteil des Supreme Court',

Süddeutsche Zeitung (Munich) 2023, 1.

[3] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, No. 20-1199 1 (US District Court for the District of Massachusetts 29 June, 2023).

[4] 'US-Supreme Court lehnt positive Diskriminierung an Unis ab',

Austria Presse Agentur (Vienna), 30 June 2023, https://science.apa.at/power-search/14090665902102260545.

[5] Sven Scharf, 'Supreme Court untersagt Studentenauswahl anhand von Hautfarbe – und das sind die Folgen',

Der Spiegel, 30 June 2023, https://www.spiegel.de/ausland/affirmative-action-supreme-court-urteil-zur-studierendenauswahl-in-den-usa-der-ueberblick-a-890969d3-6a7b-4cb6-bb91-fde0513c9f87.

[6] The claim that ‘race’ is a ‘global concept’ is made, for example by German legal scholars Cengiz Barskanmaz, and Nahed

Samour in their article Cengiz Barskanmaz and Nahed Samour, 'Das Diskriminierungsverbot aufgrund der Rasse', Maximilian Steinbeis ed.

Verfassungsblog: On Matters Constitutional,

Max Steinbeis Verfassungsblog gGmbH, 16 June 2020, https://doi.org/10.17176/20200616-124155-0, https://verfassungsblog.de/das-diskriminierungsverbot-aufgrund-der-rasse/.

[7] The history of the term ‘race’ has been written many times and most accounts reach similar conclusions. From isolated usage in European languages in the early modern period, the term solidifies into a ‘scientific’ taxonomy of the human species in the mid-18th century. For recent accounts, see George M. Fredrickson,

Racism: A Short History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002); Michael Keevak,

Becoming Yellow: A Short History of Racial Thinking (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011). 'Theories of Race: An annotated anthology of essays on race, 1684-1900', 2023, https://www.theoriesofrace.com/. The most influential of the late-18th century taxonomies is that proposed by the German physical anthropologist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in his 1775 dissertation,

De Generis Humani Varietate, which he continued to revise until the 1790s, when it was finally translated into German and other languages. Blumenbach proposed the five-part taxonomy Caucasian, Ethiopian, Mongolian, American, Malay that continues to be used today, although with a somewhat different nomenclature.

[8] David Reich,

Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past (New York: Pantheon Books, 2018), 249.

[9] Magnus Hirschfeld,

Racism, ed. and trans. Eden Paul and Cedar Paul (London: Victor Gollancz, 1938). Hirschfeld’s book makes the transition of racism from being a ‘respectable’ concept, at least in fascist circles, to an exclusively pejorative term. See Werner Sollors,

Ethnic Modernism (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 2008), 15.

[10] Gates Jr. and Curran, 'We Need a New Language'.

[11] Gates Jr. and Curran, 'We Need a New Language'.

[12] The article is: Katarzyna Bryc et al., 'The Genetic Ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States',

American Journal of Human Genetics 96, no. 1 (2015), https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.11.010.

[13] Text generated by ChatGPT, 12 November 2023, OpenAI, https://chat.openai.com.

[14] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, 27.

[15] But see J. Thomas’s concurring view: ‘race is a social construct; we may each identify as members of particular races for any number of reasons, having to do with our skin color, our heritage, or our cultural identity’.

Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, 47.

[16] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, 26. This recalls Justice Stewarts famous test for pornography: ‘I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced within that shorthand description [“hard-core pornography”], and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it’. Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S. 184, 378 U.S. Supreme Court Opinions (U.S. Supreme Court 22 June, 1964).

[17] See Christopher Hom and Robert May, 'Pejoratives as Fiction', in

Bad Words: Philosophical Perspectives on Slurs, ed. David Sosa (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 108.

[18] Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, trans. Christian Tomuschat et al. (Berlin: Federal Ministry of Justice, 19 December, 2022). https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_gg/englisch_gg.html#p0023. The original reads: ‘Niemand darf wegen seines Geschlechtes, seiner Abstammung, seiner Rasse, seiner Sprache, seiner Heimat und Herkunft, seines Glaubens, seiner religiösen oder politischen Anschauungen benachteiligt oder bevorzugt werden’.

[19] Hendrick Cremer,

"... und welcher Rasse gehören Sie an?" Zur Problematik des Begriffs "Rasse" in der Gesetzgebung, Deutsches Institut für Menschenrechte (Berlin, 2009), 4. My translation.

[20] Despite a commitment by the current coalition to replace

Rasse with a formulation such as ‘racist discrimination’, the government announced in February 2024 that it would not proceed with the plan. The main reason cited was an objection by the Jewish Council whose president, Josef Schuster, argued that the word is a reminder of the persecution and murder of millions of people – ‘primarily Jews’. Nevertheless, some individual states have removed the word from their constitutions. Vera Wolfskämpf, 'Wort "Rasse" bleibt doch im Grundgesetz',

tagesschau (Berlin) 2024, https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/grundgesetz-rasse-begriff-100.html.

[21] Barskanmaz and Samour,

Das Diskriminierungsverbot. My translation. The German original reads: ‘Rasse ist in der Welt, unser aller Sozialisierung, die Wahrnehmung dieser Welt, ist rassialisiert. Rasse gibt es nicht, aber sie wirkt’.

[22] Barskanmaz and Samour,

Das Diskriminierungsverbot. Emphasis added.

[23] See, for example, Anna von Rath and Lucy Glasser, 'Zehn schweirig zu übersetzende Begriffe in Bezug auf Race',

Goethe-Institut 2021, https://www.goethe.de/ins/us/de/kul/wir/22139756.html.The authors state that the word ‘rassialisiert’ ‘sounds strange in German. For a legal perspective, see Doris Liebscher, 'Rassialisierte Differenz im antirassistischen Rechtsstaat. Zu Genealogie und Verfasstheit von Rasse als gleichheitsrechtlicher Kategorie in Artikel 3 Absatz 3 Satz 1 Grundgesetz – und zu den Vorteilen einer postkategorialen Alternative',

Archiv des öffentlichen Rechts 146 (2021): 87. More generally: Judith Froese and Daniel Thym, eds.,

Grundgesetz und Rassismus (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2022).

[24] An example is the movement ‘EmbraceRace’ (

www.embracerace.org), which advocates even for young children to learn about racialised thinking. For this and many other examples, see Yascha Mounk,

The Identity Trap: A Story of Ideas and Power in Our Time (New York: Penguin, 2023).

[25] Ludwig Wittgenstein,

Philosophical Investigations, trans. G. E. M. Anscombe (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1958), 20.

[26] J. L. Austin,

How to Do Things with Words: The William James Lectures Delivered at Harvard University in 1955 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962), 120.

[27] The late-eighteenth century Habsburg theatre censor Franz Karl Hägelin compiled a list of words that were not permitted to be uttered on the stage under any circumstances. They included, ‘tyrant’, ‘despotism’, ‘enlightenment’, ‘liberty’, and ‘equality’, the latter two were considered to be particularly inflammatory. See Norbert Bachleitner, 'The Habsburg Monarchy', in

The Frightful Stage: Political Censorship of the Theater in Nineteenth-Century Europe, ed. Robert Justin Goldstein (New York: Berghahn Books, 2009), 236.

[28] See George Orwell: ‘The word

Fascism has now no meaning except in so far as it signifies "something not desirable."’ George Orwell, 'Politics and the English Language (1946)', in

A Collection of Essays (London: Harvest Books, 1981), 160.

[29] Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities: The Report, Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities (London, 2021), https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-report-of-the-commission-on-race-and-ethnic-disparities.

[30] This is one of John Searle’s arguments, referring to a class of facts, he terms institutional, which require speech acts to exist. See John Searle,

The Construction of Social Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1995).

bibliography

Austin, J. L.

How to Do Things with Words: The William James Lectures Delivered at Harvard University in 1955. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962.

Bachleitner, Norbert. 'The Habsburg Monarchy'. In

The Frightful Stage: Political Censorship of the Theater in Nineteenth-Century Europe, edited by Robert Justin Goldstein, New York: Berghahn Books, 2009.

Barskanmaz, Cengiz and Nahed Samour, 'Das Diskriminierungsverbot aufgrund der Rasse', Maximilian Steinbeis ed.

Verfassungsblog: On Matters Constitutional.

Max Steinbeis Verfassungsblog gGmbH, 16 June 2020, https://doi.org/10.17176/20200616-124155-0, https://verfassungsblog.de/das-diskriminierungsverbot-aufgrund-der-rasse/.

Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany. Translated by Christian Tomuschat, David P. Currie, Donald P. Kommers and Raymond Kerr. Berlin: Federal Ministry of Justice, 19 December, 2022. https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_gg/englisch_gg.html#p0023.

Bryc, Katarzyna, Eric Y. Durand, J. Michael Macpherson, David Reich and Joanna L. Mountain. 'The Genetic Ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States'.

American Journal of Human Genetics 96, no. 1 (2015): 37-53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.11.010.

Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities: The Report. Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities (London: 2021). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-report-of-the-commission-on-race-and-ethnic-disparities.

Cremer, Hendrick.

"... und welcher Rasse gehören Sie an?" Zur Problematik des Begriffs "Rasse" in der Gesetzgebung. Deutsches Institut für Menschenrechte (Berlin: 2009).

Fellmann, Fabian. 'Historisches Urteil des Supreme Court'.

Süddeutsche Zeitung (Munich), 2023, 1.

Fredrickson, George M.

Racism: A Short History. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

Froese, Judith and Daniel Thym, eds.

Grundgesetz und Rassismus. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2022.

Gates Jr., Henry Louis and Andrew Curran. 'We Need a New Language for Talking About Race'.

The New York Times (New York), 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/03/opinion/sunday/talking-about-race.html.

Heck, Johann Georg.

Bilder-Atlas zum Conversations-Lexikon: Ikonographische Encyklopädie der Wissenschaften und Künste. Vol. 1, Leipzig: Brockhaus, 1849.

Hirschfeld, Magnus.

Racism. Edited and Translated by Eden Paul and Cedar PaulLondon: Victor Gollancz, 1938.

Hom, Christopher and Robert May. 'Pejoratives as Fiction'. In

Bad Words: Philosophical Perspectives on Slurs, edited by David Sosa, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Keevak, Michael.

Becoming Yellow: A Short History of Racial Thinking. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Liebscher, Doris. 'Rassialisierte Differenz im antirassistischen Rechtsstaat. Zu Genealogie und Verfasstheit von Rasse als gleichheitsrechtlicher Kategorie in Artikel 3 Absatz 3 Satz 1 Grundgesetz – und zu den Vorteilen einer postkategorialen Alternative'.

Archiv des öffentlichen Rechts 146 (2021).

Mounk, Yascha.

The Identity Trap: A Story of Ideas and Power in Our Time. New York: Penguin, 2023.

Orwell, George. 'Politics and the English Language (1946)'. In

A Collection of Essays, London: Harvest Books, 1981.

Reich, David.

Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past New York: Pantheon Books, 2018.

Scharf, Sven. 'Supreme Court untersagt Studentenauswahl anhand von Hautfarbe – und das sind die Folgen'.

Der Spiegel, 30 June, 2023. https://www.spiegel.de/ausland/affirmative-action-supreme-court-urteil-zur-studierendenauswahl-in-den-usa-der-ueberblick-a-890969d3-6a7b-4cb6-bb91-fde0513c9f87.

Searle, John.

The Construction of Social Reality. New York: The Free Press, 1995.

Sollors, Werner.

Ethnic Modernism. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 2008.

'Theories of Race: An annotated anthology of essays on race, 1684-1900'. 2023, https://www.theoriesofrace.com/.

'US-Supreme Court lehnt positive Diskriminierung an Unis ab'.

Austria Presse Agentur (Vienna), 30 June 2023. https://science.apa.at/power-search/14090665902102260545.

von Rath, Anna and Lucy Glasser, 'Zehn schweirig zu übersetzende Begriffe in Bezug auf Race'.

Goethe-Institut 2021, https://www.goethe.de/ins/us/de/kul/wir/22139756.html.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig.

Philosophical Investigations. Translated by G. E. M. Anscombe. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1958.

Wolfskämpf, Vera. 'Wort "Rasse" bleibt doch im Grundgesetz'.

tagesschau (Berlin), 2024. https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/grundgesetz-rasse-begriff-100.html.

citation information:

Balme, Christopher, 'The uses of race: dis:connective perspectives', Ben Kamis ed. global dis:connect blog, 16 April 2024, https://www.globaldisconnect.org/04/16/the-uses-of-race-disconnective-perspectives/.

Continue Reading

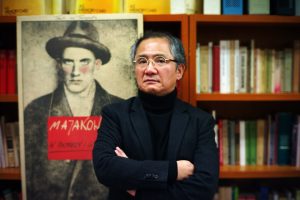

In March Jie-Hyun Lim commenced his term as a fellow at global dis:connect. Welcome.

Jie-Hyun Lim holds the CIPSH Chair of Global Easts and is a founding director of the Critical Global Studies Institute at Sogang University.

At gd:c Jie-Hyun will work on multilingual versions of victimhood nationalism as a conceptual tool to illustrate competing memories of victimhood in the postwar Vergangenheitsbewältigung across Europe and East Asia.

In March Jie-Hyun Lim commenced his term as a fellow at global dis:connect. Welcome.

Jie-Hyun Lim holds the CIPSH Chair of Global Easts and is a founding director of the Critical Global Studies Institute at Sogang University.

At gd:c Jie-Hyun will work on multilingual versions of victimhood nationalism as a conceptual tool to illustrate competing memories of victimhood in the postwar Vergangenheitsbewältigung across Europe and East Asia.

In November Andreas Greiner commenced his term as a associated fellow at global dis:connect. Welcome.

Andreas Greiner is a fellow at the German Historical Institute Washington. He specialises in infrastructure networks and their spatiality and materiality in the 19th and 20th centuries.

At gd:c Andreas is studying intercontinental civil air routes between 1919 and 1947. The project examines the codification of aerospace as well as the diplomatic and economic factors driving intercontinental airway extension.

In November Andreas Greiner commenced his term as a associated fellow at global dis:connect. Welcome.

Andreas Greiner is a fellow at the German Historical Institute Washington. He specialises in infrastructure networks and their spatiality and materiality in the 19th and 20th centuries.

At gd:c Andreas is studying intercontinental civil air routes between 1919 and 1947. The project examines the codification of aerospace as well as the diplomatic and economic factors driving intercontinental airway extension.

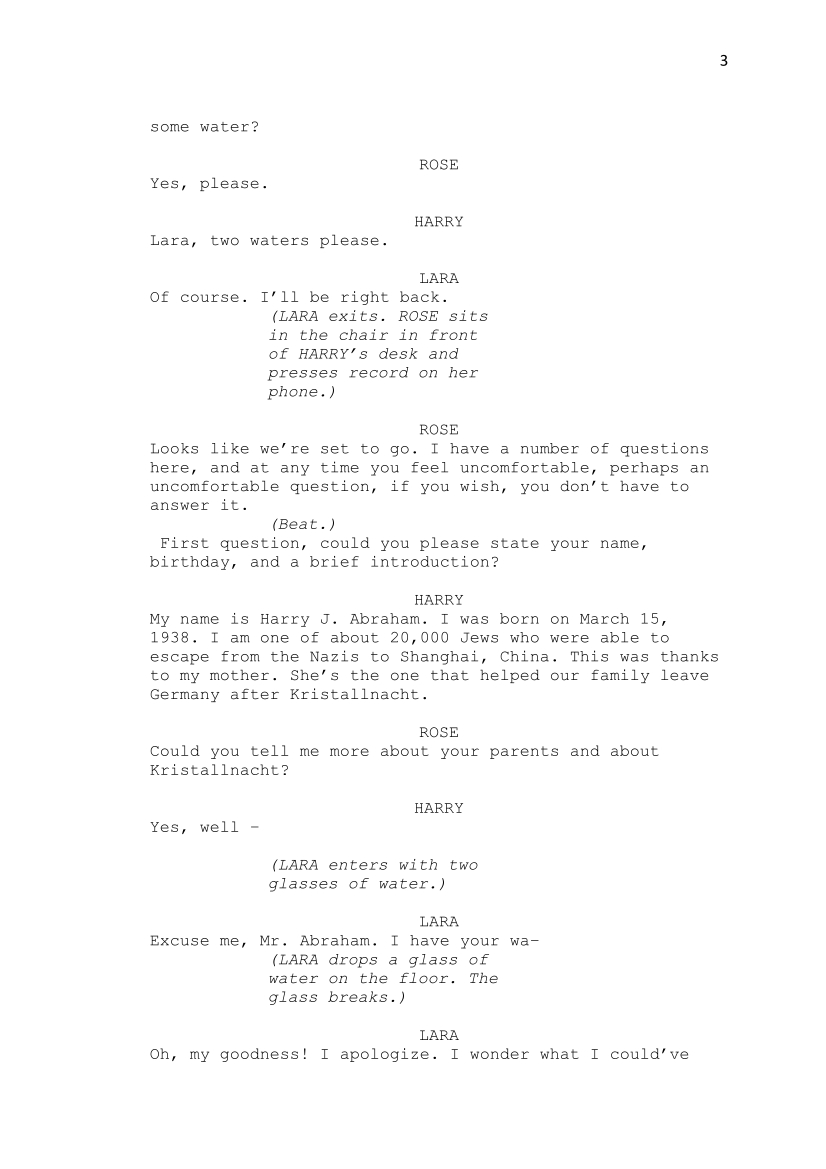

Holt’s paper, for example, evoked the relevance of mineral resources in the context of digitalisation, especially with regard to the humanities. Mineral resources make our daily life possible, though we take them for granted. Digitalisation, which is as indomitable as it is universal, also shapes our research practices and relies heavily on mineral resources. This text, for instance, was written on a laptop produced in Taiwan with mineral resources from China and Latin America, and I also use it to read digital papers by scholars from the Netherlands, the USA and India.

The more we digitalise, the more we lose a genuine connection to our analogue environment. But ironically, that same digitalisation and environmental alienation coincides with greater environmental exploitation. Materials are a medium by which we surpass our natural boundaries and enter a digital space. We do well to remember, however, that this journey is predicated on natural resources. The virtuality of digitalization is an illusion. In the end, everything is analogue.

Many of the presentations, especially those from Boddy, Grüner, Mishra and Moore highlighted the importance of reflecting on emotions in research. Art is emotion; it is, to paraphrase Benjamin Myers, the desire to cast the moment in amber.

Holt’s paper, for example, evoked the relevance of mineral resources in the context of digitalisation, especially with regard to the humanities. Mineral resources make our daily life possible, though we take them for granted. Digitalisation, which is as indomitable as it is universal, also shapes our research practices and relies heavily on mineral resources. This text, for instance, was written on a laptop produced in Taiwan with mineral resources from China and Latin America, and I also use it to read digital papers by scholars from the Netherlands, the USA and India.

The more we digitalise, the more we lose a genuine connection to our analogue environment. But ironically, that same digitalisation and environmental alienation coincides with greater environmental exploitation. Materials are a medium by which we surpass our natural boundaries and enter a digital space. We do well to remember, however, that this journey is predicated on natural resources. The virtuality of digitalization is an illusion. In the end, everything is analogue.

Many of the presentations, especially those from Boddy, Grüner, Mishra and Moore highlighted the importance of reflecting on emotions in research. Art is emotion; it is, to paraphrase Benjamin Myers, the desire to cast the moment in amber.