Tanizaki in Maputo. Japanese cultural theory and the decolonisation of architectural education in Mozambique

nikolai brandes[1]

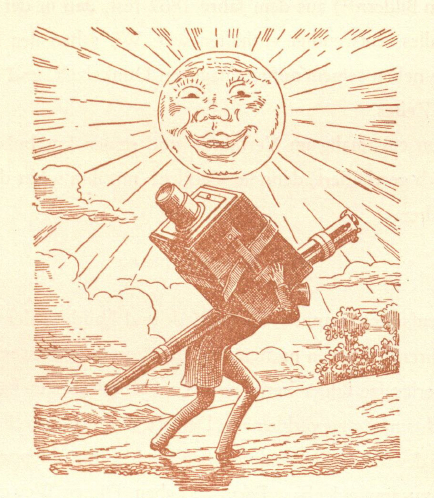

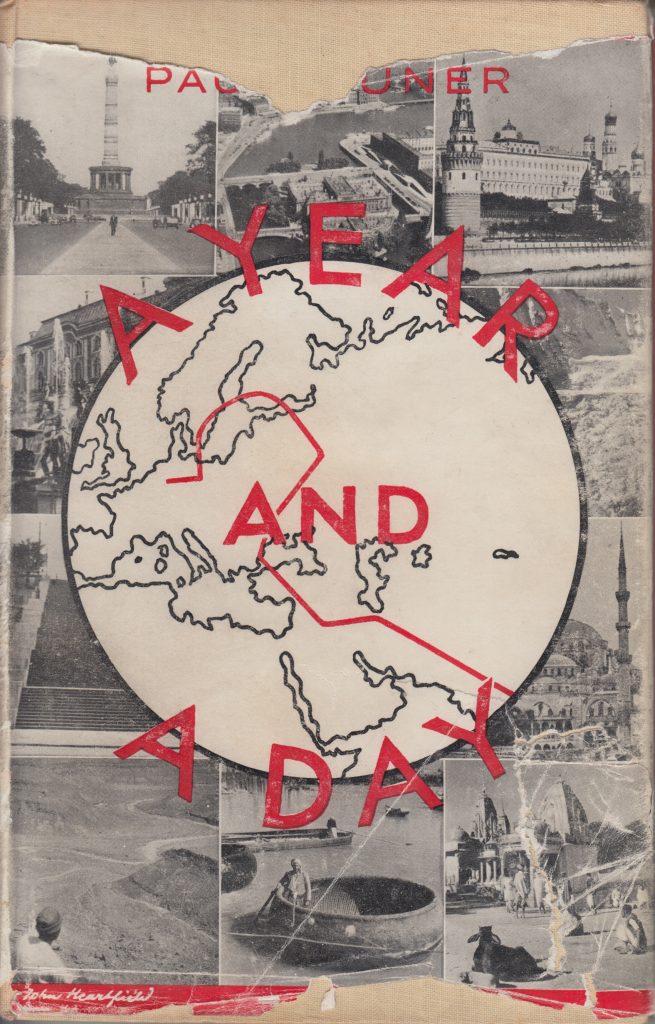

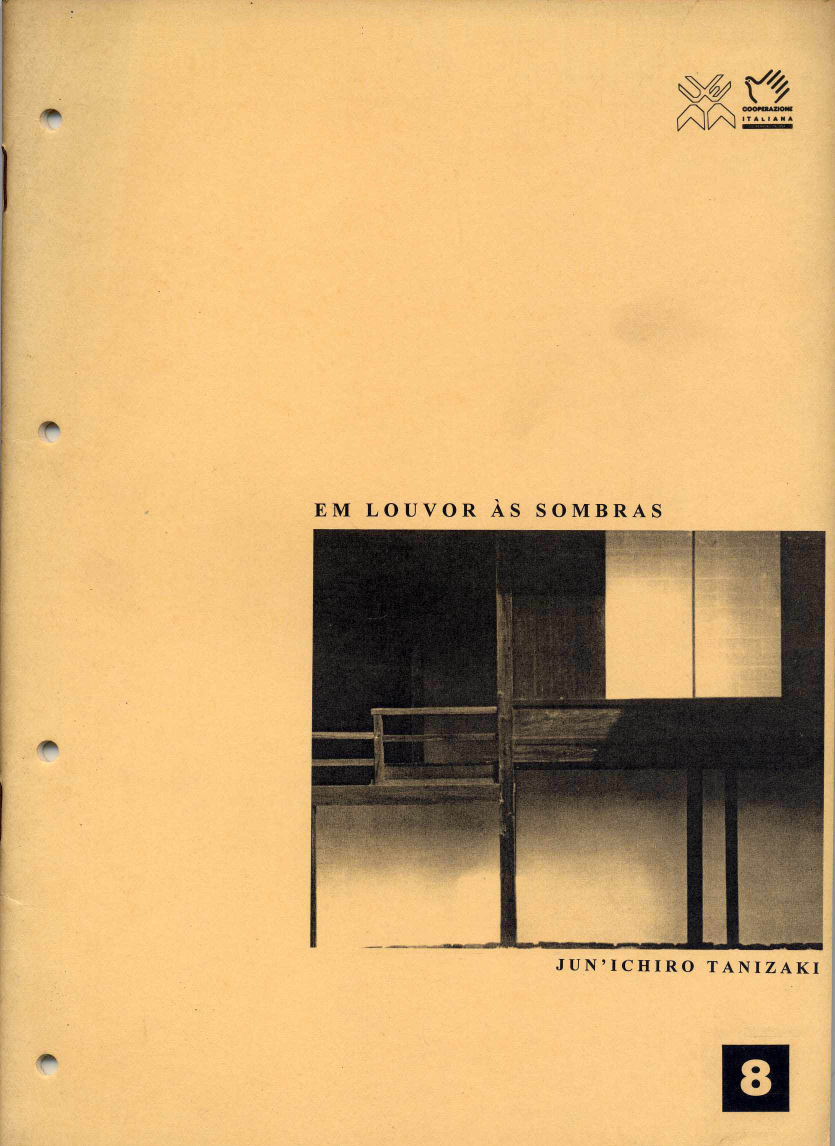

Figure 1: FAPF, front cover of the Mozambican edition of Tanizaki Jun'ichirō’s In Praise of Shadows, 1999, monochrome print, A4.

Conditions of translation

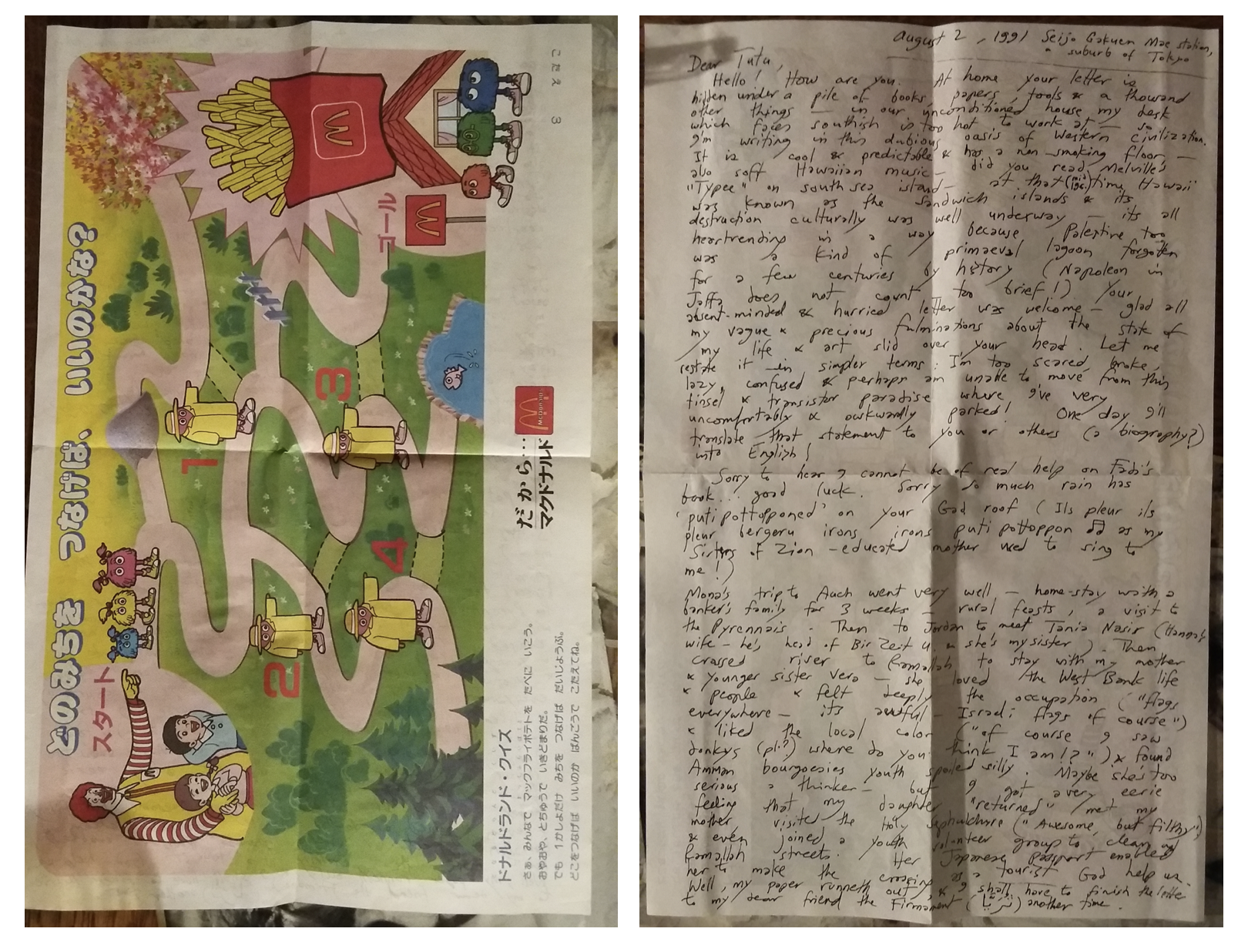

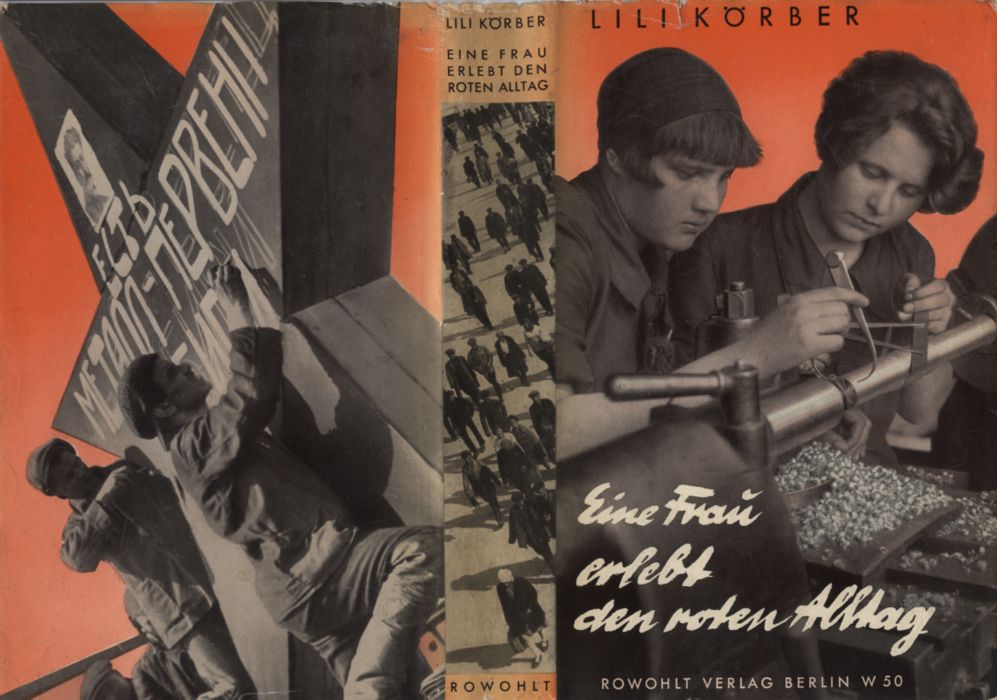

The Maputo edition, a plain, double-stapled brochure in A4 format, contains 44 pages. It was printed in black and white at the university print shop. The translation is based on the US edition and was provided by a local Portuguese UN staff member. The cover, like the text, is illustrated with architectural photographs taken from a book on Japanese architecture published in the USA in 1960. (The US edition was not illustrated.) Tanizaki’s essay develops a meandering reflection on cultural differences between Japan and Europe. It starts with architecture, touches on ideals of physical beauty, gastronomy, theatre and stagecraft, product design and the role of whiteness in Japanese identity formation, only to return repeatedly to the built environment. The author asks how cultural achievements from Japan and Europe could be integrated in equal measure in the construction of a modern house. A central feature of Japanese building culture is the use of shadows, which for Tanizaki constitutes part of Japanese aesthetics. For him, however, shadows also symbolise traditions endangered by the electric light imported from the West and the literal enlightenment of everyday life that results. Tanizaki calls for electric lights to be switched off occasionally ‘to see what it is like without them’.[7] Life without electric light: due to occasional power cuts while working in Maputo, this was probably familiar to the translator of the Mozambican edition. Her client, the FAPF, had started operations in 1986. The historical context in which the faculties in Maputo and elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa emerged have hardly been researched.[8] Apart from South Africa, where art schools were already training architects in the early 20th century, the first schools were only founded in late colonialism (Kumasi and Ibadan, 1952). In most countries, however, schools of architecture were founded after independence (Addis Ababa, 1954; Khartoum, 1957; Dar es Salaam, 1964). It took particularly long in Francophone Africa, where students of architecture necessarily made detours via Paris long after decolonisation (Lomé, 1976). The ideological orientations and institutional environments of these schools could hardly be more different. In Ethiopia, Swedish foreign aid supported the establishment of the school until experts from socialist states took over. In Togo, UNESCO set up a school that was to serve as a locus of education for all of Francophone Africa. And the structural adjustment measures of the 1990s prompted the establishment of numerous private schools across Africa. In Mozambique, founding schools was particularly challenging. The fascist government in Portugal refused decolonisation even when the African ‘wind of change’ proclaimed by British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan in 1960 became cyclonic. Until 1975, the country had to fight for liberation from colonial rule — a ‘liberation without decolonisation’, as the Mozambican historian Aquino de Bragança called it.[9] Whereas Great Britain began establishing local architecture schools from the 1950s onwards to prepare its colonies for independence, Lisbon never saw a need for such institutions. After independence, the erstwhile liberation movement rebuilt the country along Marxist-Leninist lines but remained undogmatic in its choice of international partners. In much of the country, there was war against the anti-communist RENAMO.[10] In this situation, the FAPF was founded on the initiative of José Forjaz. Forjaz, a Portuguese-born architect, worked in Mozambique as early as the 1950s, spent time in exile in Swaziland (now Eswatini) as a supporter of the liberation movement, and held key positions in the country’s public building sector after 1975. From the early 1980s, Forjaz proposed an ‘unorthodox school of architecture’ that would train ‘worker-students’ as experts in the basic needs of the population.[11] The well-connected Forjaz found allies for the budding faculty at the Sapienza Università di Roma. Lecturers from Rome were also responsible for most of the catalogue of the in-house publishing house[12] and managed the teaching until a first cohort of Mozambican architects took over.

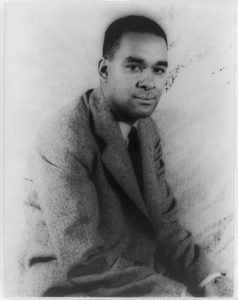

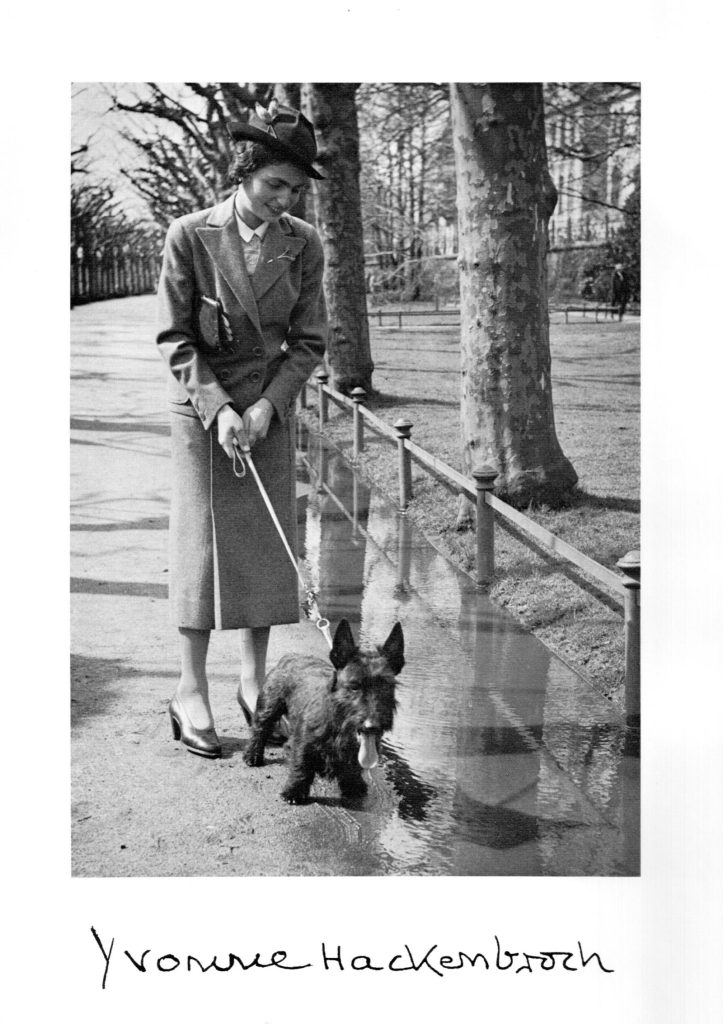

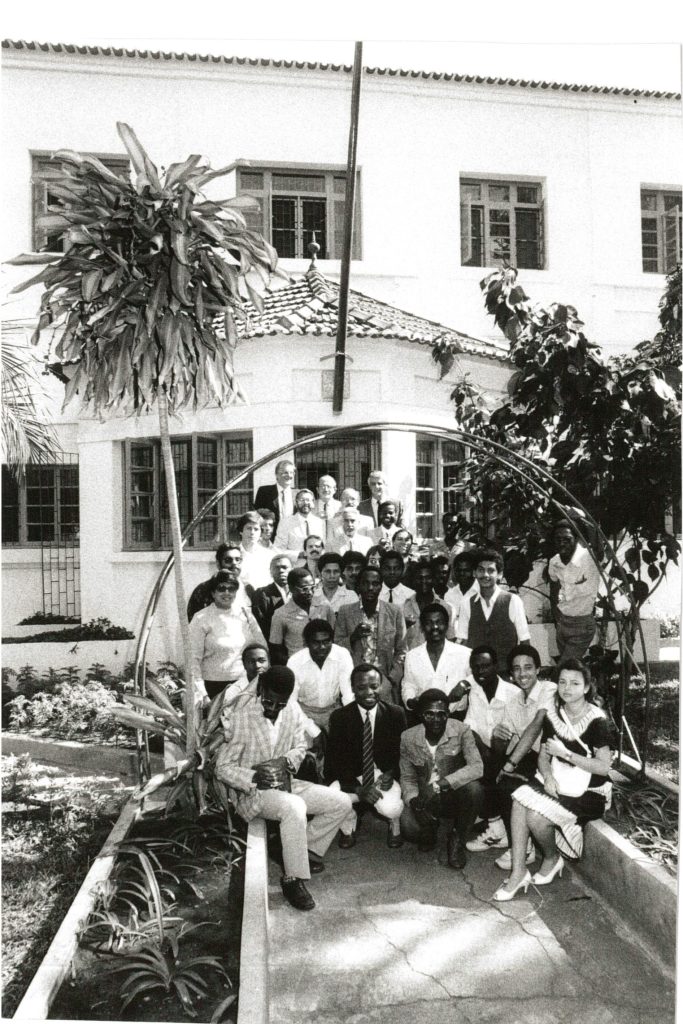

Figure 2: Lucio Carbonara, FAPF teachers and first-year students in front of the architecture institute in Maputo, 1986, photo print.

Mozambique in the architecture world

Forjaz’s enthusiasm found was grounded in Mozambique’s long-standing integration in the global architectural discourse. The money that Portugal released for its colonial containment policy in Mozambique resulted in a building boom.[13] The eccentric manifestations of this boom, influenced by Oscar Niemeyer, critical regionalism and new brutalism, also astonished Udo Kultermann, as evidenced in his reference works on African modernism.[14] Professional networks stretching as far as Brazil, Portugal, South Africa and Nigeria shaped Mozambican construction. With Pancho Guedes, a unique figure in 20th-century architecture, Mozambique was also represented at the meetings of Team Ten, the elite architects’ club of post-war modernism. After 1975, however, disconnective forces were ascendent. The country decoupled from old colonial networks. The war worried investors and disrupted attempts to build new supply chains. And the impositions of international organisations and structural adjustment programmes limited Mozambican autonomy in construction partnerships. But political flexibility, financial constraints and sovereign decision-making induced a volatile situation in which new relationships emerged. In the Mozambican construction industry of the 1980s, Chilean exiles worked alongside East German, Cuban and Bulgarian state-owned enterprises, Swedish aid workers, US volunteers and the Roman delegation to the FAPF. Establishing a school of architecture was a means for architects and planners to empower themselves and forge new, independent relationships with the world. In this context, Tanizaki’s translation was perhaps most emblematic: a local publisher had autonomously decided to draw the attention of Mozambican students to a dusty essay from a country that was almost invisible in African construction at the time. But why this particular text?Reading Tanizaki in Maputo

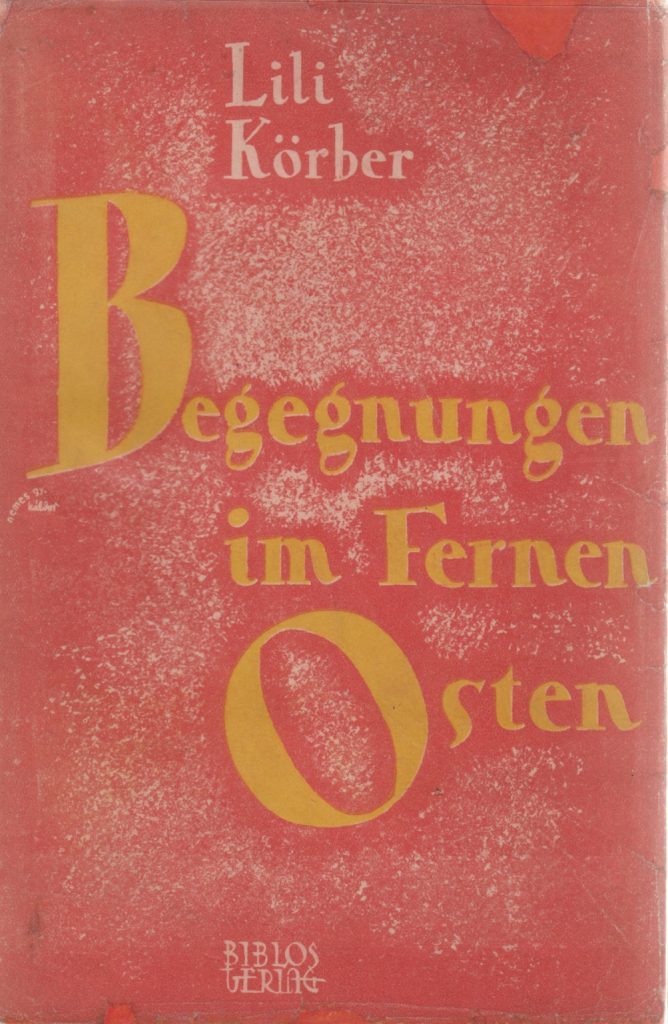

In praise of shadows was well received in architectural theory. Charles Moore, a pioneer of postmodern architecture, even wrote the foreword for the US edition. However, there is no evidence that Tanizaki circulated among African architects in the 1990s, though José Forjaz did teach in Japan. In fact, his designs may also be read as studies on shadows and shading. [Figure 3]. But local questions were what piqued interest in the text in Maputo. From the 1980s onwards, Mozambican architects such as Luis Lage, João Tique and Mário do Rosário at the FAPF had been looking for ways to cope with the country’s pressing building tasks — especially the construction of housing, schools and clinics — despite poverty and shortages of materials and skilled labour.

Figure 3: Nikolai Brandes, Escola Secundária da Polana (Forjaz and Tinoco, ca 1973), Maputo, 2012, digital photograph.

The regular, linear and monumental pattern of grand avenues and boulevards and monumental squares do not in fact serve any identifiable use or have a clear meaning for the majority of our population. But they are still being designed and built. [A] productive use of land […] balanced with a regular distribution of market and service centres minimizing transport needs and providing employment could […] create a new […] urban environment. […] With our negative, stagnant or barely positive rates of economic growth against the explosive demographic growth it is vital to find alternatives to classic development strategies. The people of our cities are finding those alternatives by themselves and it is our responsibility as planners and architects to understand their ways and to help them resolve better the spatial problems that they face.[17]The opposition to imported technocratic expertise and directives of international donor agencies and the preference for local solutions had a distinctly disconnective, isolationist component. And yet, as an epistemological project, it was embedded in global discussions. In architecture, site-specific ways of life, architectural styles and building materials received increasing international attention by the 1970s. With the end of the great modernisation narratives, corresponding tendencies found expression in other fields too, first and foremost in social science. Paralleling postcolonial construction research at the FAPF, Mozambique saw the emergence of public intellectuals such as Aquino de Bragança, who viewed the anti-colonial liberation struggle as an incubator for new, practical knowledge about social dynamics. The rediscovery of these specifically Mozambican approaches was essential to the ‘epistemology of the South’, which sparked international interest in the social sciences.[18] Mozambique, however, not only contributed to a global discourse on local knowledge but also made use of geopolitically surprising models. For the editors at FAPF, Tanizaki had apparently raised questions in 1930s Japan that seemed significant for the future of architecture in postcolonial Mozambique.[19] Tanizaki discusses domains in which Japanese products, techniques and cultural practices are superior to Western innovations, from the quality of writing paper to optimising the interior climate of living spaces and the haptic quality of lacquerware crockery. However, he is not only concerned with nostalgia for a past universe. Rather, conservative Tanizaki is concerned about the disappearance of a material culture in which formal design and social practice meaningfully interpenetrate. The motif of shadows that characterises his description of architecture with semi-transparent paper walls and dark alcoves recurs consistently in other miniatures on Japanese society, especially when he declares particular technical and cultural imports from the West to be simply unsuitable to local needs. For example, he accuses the phonograph of cementing a Western understanding of music and sound that underrates pauses (the acoustic equivalent of shadows) in Japanese oral and musical culture. If modern medicine had originated in Japan, he suspects, the bedrooms of hospitals would not be white, but sand-coloured, and thus more beneficial to recovery processes. ‘Here again we have to come off the loser for having borrowed’,[20] he writes. Similarly, Forjaz fears that the ‘systematic adoption of values and forms imported from other cultures and societies’[21] might dramatically worsen the living conditions in Mozambican cities. What Tanizaki and Forjaz have in common is the concern about technological globalisation, which standardises uniform, often unsuitable solutions. But while Tanizaki nostalgically bids farewell to local idiosyncrasies, Forjaz thinks of the local more hopefully as a laboratory for future innovation:

Our role as architects and planners in the Third World is, primarily, to deepen the understanding of the economic, social and cultural characteristics of our society, and their dynamics of change in order to find adequate and necessarily new solutions to our spatial and building problems.[22]Compared to Tanizaki, Forjaz is clearly anti-traditionalist. Genuine and contemporary Mozambican architecture is yet to come:

Traditional societies in our region did not have to answer this scale of problems […]. We have to create now an architecture that expresses our new social order, and there is not much we can take from our architectural traditions. […] Like the cities of Europe […] need their cathedrals and their castles, their walls and great squares; like the typical American city needs its courthouse square and church, we need our tangible signs of an order superior to the tribal and different from the colonial.[23]In Mozambique, the international disconnect caused by extreme economic and political circumstances even invigorated participation in global academic discourses and prompted contributions to global transfers of theory. A particularly unusual publication, this Mozambican edition also highlights the obstacles that continue to exclude African universities from global academic publishing. At the time, the decision to publish Tanizaki fit the search for a genuine path in the field of architecture, and it again relates to current discussions in South Africa and Great Britain about decolonising architectural education. [1] This text was facilitated by a research grant from the German Historical Institute in Rome. [2] See Faculdade de Arquitectura e Planeamento Físico, Publicações FAPF (Maputo: Edições FAPF, ca. 2005). [3] See Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, Em Louvor às sombras, trans. Margarida David e Silva (Maputo: Edições FAPF, 1999). [4] In the year of the translation, Mozambique ranked third to last in the UNDP’s Human Development Index, see ‘Human Development Index’, ed. UNDP (2023). https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/human-development-index#/indicies/HDI.. [5] See José Forjaz, ‘Research Needs and Priorities in Housing and Construction in Mozambique’, Habitat Intl. 9, no. 2 (1985). [6] That is, Western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic. [7] See Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, trans. Thomas J. Harper (Stony Creek: Leet's Island Books, 1977), 42.. [8] For an attempt in this direction, see Mark Olweny, ‘Architectural Education in Sub-Saharan Africa: An Investigation into Pedagogical Positions and Knowledge Frameworks’, Journal of Architecture 25, no. 6 (2022). [9] See Aquino de Bragança, ‘Independência sem descolonização: A transferência do poder em Moçambique, 1974 – 1975’, Estudos Moçambicanos 5-6 (1985). [10] See Marina Ottaway, ‘Afrocommunism Ten Years after: Crippled but Alive’, Issue: A Journal of Opinion 16, no. 1 (1987). [11] José Forjaz, Por uma escola de arquitectura não ortodoxa, ca. 1983, handwritten manuscript, FAPF archive, Maputo. [12] Some of these publications were pioneering works on Mozambican architectural history. [13] See Nikolai Brandes, ‘Developing the Late Colonial City: Strategies of a Middle Class Housing Cooperative in Mozambique, 1951–1975’, Cities 130, 103935 (2022), https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.103935. [14] See Udo Kultermann, New Directions in African Architecture (New York: George Braziller, 1969). [15] Nikolai Brandes, ‘“Das Ziel waren Wohnungen für die ganze Bevölkerung.” Ein Gespräch mit dem mosambikanischen Architekten Mário do Rosário, der in Maputo die Umsetzung eines der letzten Wohnungsbauprojekte der DDR im Ausland begleitete’, in Architekturexport DDR. Zwischen Sansibar und Halensee, ed. Andreas Butter and Thomas Flierl (Berlin: Lukas, 2023). [16] The essay first appeared in Arquitrave, the FAPF's student magazine, in 1990; in English translation in an exhibition catalogue in 1999; and finally on the website of Forjaz's architecture firm. I follow the online publication: ‘Between Adobe and Stainless Steel’, José Forjaz Arquitectos, 2021, accessed 6 September, 2023, https://www.joseforjazarquitectos.com/textosen/%E2%80%9C...between-adobe-and-stainless-steel%E2%80%9D. [17] Forjaz, ‘Between Adobe’. [18] See Boaventura Santos, ‘Aquino de Bragança: criador de futuros, mestre de heterodoxias, pioneiro das epistemologias do Su’, in Como fazer ciências sociais e humanas em África. Questões epistemológicas, metodológicas, teóricas e políticas, ed. Teresa Cruz e Silva, João Paulo Borges Coelho, and Amélia Neves de Souto (Dakar: CODESRIA, 2012). [19] This transfer of ideas is ironic in that Japan itself was aggressively building an empire at the time of Tanizaki's stance against Western cultural influence. [20] Tanizaki, In Praise, 12. [21] Forjaz, ‘Between Adobe’. [22] Forjaz, ‘Between Adobe’. [23] Forjaz, ‘Between Adobe’.

Holt’s paper, for example, evoked the relevance of mineral resources in the context of digitalisation, especially with regard to the humanities. Mineral resources make our daily life possible, though we take them for granted. Digitalisation, which is as indomitable as it is universal, also shapes our research practices and relies heavily on mineral resources. This text, for instance, was written on a laptop produced in Taiwan with mineral resources from China and Latin America, and I also use it to read digital papers by scholars from the Netherlands, the USA and India.

The more we digitalise, the more we lose a genuine connection to our analogue environment. But ironically, that same digitalisation and environmental alienation coincides with greater environmental exploitation. Materials are a medium by which we surpass our natural boundaries and enter a digital space. We do well to remember, however, that this journey is predicated on natural resources. The virtuality of digitalization is an illusion. In the end, everything is analogue.

Many of the presentations, especially those from Boddy, Grüner, Mishra and Moore highlighted the importance of reflecting on emotions in research. Art is emotion; it is, to paraphrase Benjamin Myers, the desire to cast the moment in amber.

Holt’s paper, for example, evoked the relevance of mineral resources in the context of digitalisation, especially with regard to the humanities. Mineral resources make our daily life possible, though we take them for granted. Digitalisation, which is as indomitable as it is universal, also shapes our research practices and relies heavily on mineral resources. This text, for instance, was written on a laptop produced in Taiwan with mineral resources from China and Latin America, and I also use it to read digital papers by scholars from the Netherlands, the USA and India.

The more we digitalise, the more we lose a genuine connection to our analogue environment. But ironically, that same digitalisation and environmental alienation coincides with greater environmental exploitation. Materials are a medium by which we surpass our natural boundaries and enter a digital space. We do well to remember, however, that this journey is predicated on natural resources. The virtuality of digitalization is an illusion. In the end, everything is analogue.

Many of the presentations, especially those from Boddy, Grüner, Mishra and Moore highlighted the importance of reflecting on emotions in research. Art is emotion; it is, to paraphrase Benjamin Myers, the desire to cast the moment in amber.